Jesus, Paul, and the Temple: an Exploration of Some Patterns of Continuity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Two Answers to the Challenge of Jesus

TWO ANSWERS TO THE CHALLENGE OF JESUS. HV w i i.i.i am WEBER. i < Continued) T1IF Cleansing of the Temple has a double aspect It was, on the one hand, an attack upon the chief priests and their allies, the scribes. On the other hand, it was a bold stroke for the re- ligions liberty of the people. From both sides there must have come an answer. His enemies could not simply ignore what happened. Unless they were ready to accept the Galilean as their master, they were compelled to think of ways and means by which to defeat him. At the same time, his friends and admirers would discuss his valiant deed and formulate certain conclusions as to his character and authority, the more so as the chief priests themselves had first broached that question in public. Thus we may expect a twofold answer to the challenge of Jesus provided the Gospels have pre-erved a complete account. The story of the Cleansing of the Temple is not continued at once. It is followed in all four Gospels by a rather copious collec- tion of sayings of Jesus. Especially the Synoptists represent him as teaching in the temple as well as on his way to and from that sanc- tuary. Those teachings consist of three groups. The first com- prises parables and sayings which are found in one Gospel only. The second contains discourses vouched tor by two oi the Gospels. The third belongs to all three. The first two groups may be put aside without any further examination because they do not form part of the common Synoptic source. -

When Jesus Threw Down the Gauntlet

WHEN JESUS THREW DOWN THE GAUNTLET. BY WM. WEBER. THE death of Jesus, whatever else it may be, is a very important event in the history of the human race. As such it forms a Hnk in the endless chain of cause and effect ; and we are obliged to ascertain, if possible, the facts which led up to the crucifixion and rendered it inevitable. The first question to be answered is : Who were the men that committed what has been called the greatest crime the world ever saw ? A parallel question asks : How did Jesus provoke the resent- ment of those people to such a degree that they shrank not even from judicial murder in order to get rid of him? The First Gospel denotes four times the persons who engineered the death of Jesus "the chief priests and the elders of the people." The first passage where that happens is connected with the account of the Cleansing of the Temple (Matt. xxi. 23.) The second treats of the meeting at which it was decided to put Jesus out of the way. ( Matt. xxvi. 3.) The third tells of the arrest of Jesus. (Matt. xxvi. 47.) The fourth relates how he was turned over to the tender mercies of Pontius Pilate. ( Matt, xx vii. 1 ) The expression is used, as . appears from this enurrieration, just at the critical stations on the road to Calvary and may be a symbol characteristic of the principal source of the passion of Jesus in Matthew. The corresponding term of the Second and Third Gospels is "the chief priests and the scribes" : but that is not used exclusively in all the parallels to the just quoted passages. -

Jesus in Film: Hollywood Perspectives on the Jewishness of Jesus

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 2 Issue 2 October 1998 Article 2 October 1998 Jesus in Film: Hollywood Perspectives on the Jewishness of Jesus Adele Reinhartz [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf Recommended Citation Reinhartz, Adele (1998) "Jesus in Film: Hollywood Perspectives on the Jewishness of Jesus," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 2 : Iss. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol2/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jesus in Film: Hollywood Perspectives on the Jewishness of Jesus Abstract The purpose of this article is to survey a number of Jesus movies with respect to the portrayal of Jesus' Jewishness. As a New Testament scholar, I am curious to see how these celluloid representations of Jesus compare to academic depictions. For this reason, I begin by presenting briefly three trends in current historical Jesus research that construct Jesus' Jewishness in different ways. As a Jewish New Testament scholar, however, my interest in this question is fuelled by a conviction that the cinematic representations of Jesus both reflect and also affect cultural perceptions of both Jesus and Judaism. My survey of the films will therefore also consider issues of reception, and specifically, the image of Jesus and Judaism that emerges from each. This article is available in Journal of Religion & Film: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol2/iss2/2 Reinhartz: Jesus in Film Jesus of Nazareth is arguably the most ubiquitous figure in western culture. -

Harmony of the Gospels

Harmony of the Gospels INTRODUCTIONS TO JESUS CHRIST Date Event Location Matthew Mark Luke John (1) Luke’s Introduction 1:1-4 (2) Pre-incarnation Work of Christ 1:1-18 (3) Genealogy of Jesus Christ 1:1-17 3:23-38 BIRTH, INFANCY, AND ADOLESCENCE OF JESUS AND JOHN THE BAPTIST Date Event Location Matthew Mark Luke John 7BC (1) Announcement of Birth of John the Baptist Jerusalem (Temple) 1:5-25 7/6BC (2) Announcement of Jesus’ Birth to Mary Nazareth 1:26-38 6/5BC (3) Song of Elizabeth to Mary Hill Country of Judah 1:39-45 (4) Mary’s Song of Praise 1:46-56 c.5BC (5) Birth of John the Baptist, His Father’s Song Judea 1:57-80 5BC (6) Announcement of Jesus’ Birth to Joseph Nazareth 1:18-25 5-4BC (7) Birth of Jesus Christ Bethlehem 1:24,25 2:1-7 (8) Proclamation by the Angels Near Bethlehem 2:8-14 (9) The Shepherds Visit Bethlehem 2:15-20 (10) Jesus’ Circumcision Bethlehem 2:21 (11) Witness of Simeon & Anna Jerusalem 2:22-38 (12) Visit of the Magi Jerusalem & Bethlehem 2:1-12 (13) Escape to Egypt & Murder of Babies Bethlehem 2:13-18 (14) From Egypt to Nazareth with Jesus 2:19-23 2:39 Afterward (15) Childhood of Jesus Nazareth 2:40,51 7/8AD (16) 12 year old Jesus Visits the Temple Jerusalem 2:41-50 Afterward (17) Summary of Jesus’ Growth to Adulthood Nazareth 2:51,52 TRUTHS ABOUT JOHN THE BAPTIST Date Event Location Matthew Mark Luke John c.28-30AD (1) John’s Ministry Begins Judean Wilderness 3:1 1:1-4 3:1,2 1:19-28 (2) Man and Message 3:2-12 1:2-8 3:3-14 (3) His Picture of Jesus 3:11,12 1:7,8 3:15-18 1:26,27 (4) His Courage 14:4-12 3:19,20 BEGINNING -

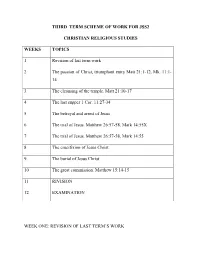

Third Term Jss 2 C

THIRD TERM SCHEME OF WORK FOR JSS2 CHRISTIAN RELIGIOUS STUDIES WEEKS TOPICS 1 Revision of last term work 2 The passion of Christ, triumphant entry Matt 21:1-12, Mk. 11:1- 14 3 The cleansing of the temple. Matt 21:10-17 4 The last supper 1 Cor. 11:27-34 5 The betrayal and arrest of Jesus 6 The trial of Jesus. Matthew 26:57-58, Mark 14:55X 7 The trial of Jesus. Matthew 26:57-58, Mark 14:55 8 The crucifixion of Jesus Christ 9. The burial of Jesus Christ 10 The great commission. Matthew 15:14-15 11 RIVISION 12 EXAMINATION WEEK ONE: REVISION OF LAST TERM’S WORK WEEK TWO TOPIC: THE PASSION OF CHRIST TRIUMPHANT ENTRY INTO JERUSALEM (THE PASSION) MARK 11:1- 11, MATTHEW 21:1-11 Jesus had started His earthly ministry for good three years. He has been going from one place to another preaching, teaching people about the kingdom of God. During the Passover festival celebration in Jerusalem, Jesus wanted to go down to Jerusalem. As He was going with His disciples, they passed through Samaria and entered Jericho. When they came near Jerusalem to Bethany at the mount of olive they stopped there and He sent out two of his disciples to Bethany to bring back to Him a colt of an ass which had never been driven by anyone. He told them if anyone should challenge them, their reply would be the Lord needed it. And after use, if would be sent back. They went and found the colt and they brought it to Jesus. -

Jesus' Intervention in the Temple

JETS 58/3 (2015) 545–69 JESUS’ INTERVENTION IN THE TEMPLE: ONCE OR TWICE? ALLAN CHAPPLE* The Gospel of John has Jesus intervening dramatically in the TemplE (John 2:13–22) before he bEgins his public ministry in Galilee (John 3:24; 4:3; cf. Mark 1:14). HowevEr, the only such event rEported in the Synoptics occurs at the end of Jesus’ ministry (Mark 11:15–18 and parallels). What are wE to makE of this discrep- ancy? Logically, there are four possible explanations: 1. The Synoptics are right about when the event took place—so that John has moved it to the beginning of the ministry, presumably for theological reasons. This is the view of the overwhelming majority. 2. John is right about when this happened—so the Synoptic Gospels have moved it to the end of Jesus’ ministry (again, presumably for theological reasons).1 3. NeithEr the Synoptics nor John have got it right, because no such event oc- curred.2 * Allan ChapplE is SEnior LEcturEr in NT at Trinity ThEological CollEgE, P.O. Box 115, LEEdErvillE, Perth, WA 6902, Australia. 1 SEE, E.g., Paul N. AndErson, The Fourth Gospel and the Quest for Jesus: Modern Foundations Reconsidered (LNTS 321; London: T&T Clark, 2006) 158–61; F.-M. Braun, “L’expulsion dEs vEndEurs du TemplE (Mt., xxi, 12–17, 23–27; Mc., xi, 15–19, 27–33; Lc., xix, 45–xx, 8; Jo., ii, 13–22),” RB 38 (1929) 188–91; R. A. Edwards, The Gospel according to St. John: Its Interpretation and Criticism (London: EyrE & SpottiswoodE, 1954) 37–38; A. -

Jesus As Priest in the Gospels Nicholas Perrin

Jesus as Priest in the Gospels Nicholas Perrin Nicholas Perrin is the Franklin S. Dryness Chair of Biblical Studies at Wheaton Grad- uate School and the former Dean of Wheaton Graduate School at Wheaton College. He earned his PhD from Marquette University. Most recently, he is the author of Jesus the Priest (SPCK/Baker Academic, 2018) and will also be publishing The Kingdom of God (Zondervan) in early 2019. A husband and the father of two grown sons, Dr. Perrin is a teaching elder in the Presbyterian Church in America. To the extent that New Testament (NT) Theology is concerned to convey the theologies of the NT writings as these have been critically interpreted, the project by nature entails a good deal of interpretative retrieval, that is, an up-to-date recounting of standard arguments and familiar paradigms for understanding the discrete canonical texts. One such “familiar paradigm,” easily demonstrable from the past hundred years or so of scholarly literature, holds that the Epistle to the Hebrews is unique by virtue of its emphasis on Jesus’ priesthood. From here, especially if one prefers to date Hebrews after the destruction of the temple, it is a straightforward move to infer that the concept of Jesus’ priesthood was entirely a post-Easter theologoumenon, likely occasioned by the destruction of the Jerusalem temple, and almost certainly limited in importance so far as first-century Christian belief was concerned. Whatever factors “in front of” the biblical text may have helped pave the way for this recurring interpretative judgment (here one may think, for example, of the fierce anti-sacerdotal character of so much nineteenth- and twenti- eth-century Protestant theology), it almost certainly mistaken. -

The Cleansing of the Temple in the Fourth Gospel As a Call to Action for Social Justice

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University MA in Religion Theses Department of Religious Studies and Philosophy 2014 The leC ansing of the Temple in the Fourth Gospel as a call to action for social justice Douglas Thompson Goodwin Gardner-Webb University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/religion_etd Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, and the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Goodwin, Douglas Thompson, "The leC ansing of the Temple in the Fourth Gospel as a call to action for social justice" (2014). MA in Religion Theses. 1. https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/religion_etd/1 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Religious Studies and Philosophy at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in MA in Religion Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please see Copyright and Publishing Info. THE CLEANSING OF THE TEMPLE IN THE FOURTH GOSPEL AS A CALL TO ACTION FOR SOCIAL JUSTICE By Douglas Thompson Goodwin A thesis submitted to the faculty of Gardner-Webb University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Religious Studies and Philosophy Boiling Springs, NC 2014 Approved by: ___________________________ ___________________________ Scott Shauf, Advisor Kent Blevins, MA Coordinator ___________________________ ___________________________ James McConnell, Reader Eddie Stepp, Department Chair ___________________________ Steven Harmon, Reader GARDNER-WEBB UNIVERSITY BOILING SPRINGS, NORTH CAROLINA THE CLEANSING OF THE TEMPLE IN THE FOURTH GOSPEL AS A CALL TO ACTION FOR SOCIAL JUSTICE SUBMITTED TO DR. -

The Cleansing of the Temple in Four Jesus Films

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 13 Issue 2 October 2009 Article 5 October 2009 God in the Details: The Cleansing of the Temple in Four Jesus Films David Landry University of St. Thomas, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf Recommended Citation Landry, David (2009) "God in the Details: The Cleansing of the Temple in Four Jesus Films," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 13 : Iss. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol13/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. God in the Details: The Cleansing of the Temple in Four Jesus Films Abstract An effective technique for teaching religion/theology students the virtues of "close reading" of films and the various techniques by which filmmakers communicate meaning to their audiences involves the comparison of the same biblical scene in different filmed versions of the life of Jesus. Students can learn to appreciate the significance of the ariousv theological and aesthetic choices a particular Jesus film represents by becoming aware of the very different choices made by the makers of other Jesus films. The scene used to illustrate this technique in this paper is the cleansing of the Temple, and the films whose portrayal of this scene are analyzed are The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), The King of Kings (1927), Jesus Christ Superstar (1973), and Jesus of Montreal (1989). -

The Cleansing of the Temple According to Mark the Cleansing of the Temple Is One of Those Rare Stories That Is Told in All Four Gospels

The Cleansing of the Temple According to Mark The Cleansing of the Temple is one of those rare stories that is told in all four Gospels. This Sunday’s Gospel presents John’s account. True to his overriding theme, John emphasizes Christ’s divinity and presents the reason for the Cleansing as Christ replacing the temple as the center of worship. “Destroy this temple (that is, Christ) and in three days I will raise it up (John 2:19).” John places this scene at the beginning of Jesus’ ministry as opposed to the Synoptic Gospels who place it at the end. Right up front, like an overture of an opera, John delivers his thesis: Jesus is the Christ—the divine Son of God. Mark’s Gospels seems to have a different purpose for the Cleansing. He sandwiches the story in the middle of an odd story of Jesus cursing an unfruitful fig tree. Before the Cleansing, Jesus approaches a fig tree and sees that it has no produce on it. Mark tells us that “it was not the time for figs (Mark 11:13).” He’s telling us that Jesus’ curse isn’t directed so much at that particular tree but rather that he is making a symbolic statement. The Adam and Eve story of the Eating of the Fruit never mentions the type of fruit. For unusual reasons, we tend to think of the fruit as the apple, but the Jews of Jesus’ day believed it was a fig—a much better guess, given that Adam and Eve made garments of fig leaves. -

Gospel Chronologies, the Scene at the Temple, and the Crucifixion of Jesus

Gospel Chronologies, the Scene at the Temple, and the Crucifixion of Jesus Paula Fredriksen Department of Religion, Boston University (forthcoming in the Catholic Biblical Quarterly) I. The Death of Jesus and the Scene at the Temple The single most solid fact we have about Jesus’ life is his death. Jesus was crucified. Thus Paul, the gospels, Josephus, Tacitus: the evidence does not get any better than this.1 This fact, seemingly simple, implies several others. If Jesus died on a cross, then he died by Rome’s hand, and within a context where Rome was concerned about sedition. But against this fact of Jesus’ crucifixion stands another, equally incontestable fact: although Jesus was executed as a rebel, none of his immediate followers was. We know from Paul’s letters that they survived. He lists them as witnesses to the Resurrection (1 Cor 15:3-5), and he describes his later dealings with some (Galatians 1-2). Stories in the gospels and in Acts confirm this information from Paul. Good news, bad news. The good news is that we have two firm facts. The bad news is that they pull in different directions, with maximum torque concentrated precisely at Jesus’ solo crucifixion. Rome (as any empire) was famously intolerant of sedition. Josephus provides extensive accounts of other popular Jewish charismatic figures to either side of Jesus’ lifetime: they were cut down, together with their followers.2 If Pilate had seriously thought that Jesus were politically dangerous in the way that crucifixion implies, more than Jesus would have died;3 and certainly the community of Jesus’ followers would not have been able to set up in Jerusalem, evidently unmolested by Rome for the six years or so that Pilate remained in office. -

Third Sunday of Lent Homily 2015

Third Sunday of Lent Homily 2015 Spiritual Spring Cleaning “God’s temple is holy, and you are that temple.” St. Augustine Our Gospel passage today is one the few found in all four Gospels. The Synoptics place the event of Jesus chasing out the money changers from the temple during Holy Week. The fourth Gospel makes the story the beginning of Jesus’ ministry. Some scholars suggest that this event is ultimately what got Jesus arrested. For the author of the fourth Gospel, however, this event begins Jesus’ public ministry. There are many interpretations among biblical scholars as to what Jesus was actually doing. Some suggest that he was symbolically destroying the temple cult. There was a great deal of tension between the kingdom of God movement headed by a certain Galilean peasant and the temple’s wealthy priests, who were hated as Roman collaborators. The Jerusalem temple was one of the wonders of the ancient world. It was the length of four and half football fields in length and was 10 to 16 stories high. Jerusalem swelled from 50,000-150,000 pilgrims at Passover. Both Jewish and Roman leaders were on edge and hyperalert for trouble makers. To help put things in perspective, around 25,000 lambs were sacrificed for the feast in the temple. Pilate was terribly ruthless and would come in from Ceasera Maritima to Jerusalem just in case there was a riot or worse. He hated the Jews and would be eventually dismissed from his post as governor because of his ruthlessness. Jesus’ actions in the temple during Holy Week have been interpreted by many as a “cleansing of the temple”.