Grace in the Sermon on the Mount by Charles H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sermon on the Mount 12 Studies for Individuals Or Groups

Over 10 Million LifeGuides Sold SERMON ON THE MOUNT 12 STUDIES FOR INDIVIDUALS OR GROUPS John Stott A Life G uide ® B ible S tudy A LifeGuide® Bible Study SERMON ON THE MOUNT 12 STUDIES FOR INDIVIDUALS OR GROUPS John Stott With Notes for Leaders InterVarsity Press P.O. Box 1400, Downers Grove, IL 60515 World Wide Web: www.ivpress.com E-mail: [email protected] ©1987, 2000 by John Stott This guide makes use of material originally published in The Message of the Sermon on the Mount ©1978 by John R.W. Stott. Originally published under the title Christian Counter-Culture. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from InterVarsity Press—with the exception of the following: As the purchaser of this LifeGuide® Bible Study title from www.ChristianBibleStudies.com, you may print and distribute up to 1,000 copies provided that (1) the copies are used in your church, organization or ministry only, (2) they are distributed without charge (including tuition or entrance fee), and (3) you do not change or remove InterVarsity Press’s copyright information. See the last page of this book for examples of what is included or not included with this 1,000-user license. InterVarsity Press® is the book-publishing division of InterVarsity Christian Fellowship/USA®, a movement of students and faculty active on campus at hundreds of universities, colleges and schools of nursing in the United States of America, and a member movement of the International Fellowship of Evangelical Students. For information about local and regional activities, write Public Relations Dept., InterVarsity Christian Fellowship/USA, 6400 Schroeder Rd., P.O. -

Two Answers to the Challenge of Jesus

TWO ANSWERS TO THE CHALLENGE OF JESUS. HV w i i.i.i am WEBER. i < Continued) T1IF Cleansing of the Temple has a double aspect It was, on the one hand, an attack upon the chief priests and their allies, the scribes. On the other hand, it was a bold stroke for the re- ligions liberty of the people. From both sides there must have come an answer. His enemies could not simply ignore what happened. Unless they were ready to accept the Galilean as their master, they were compelled to think of ways and means by which to defeat him. At the same time, his friends and admirers would discuss his valiant deed and formulate certain conclusions as to his character and authority, the more so as the chief priests themselves had first broached that question in public. Thus we may expect a twofold answer to the challenge of Jesus provided the Gospels have pre-erved a complete account. The story of the Cleansing of the Temple is not continued at once. It is followed in all four Gospels by a rather copious collec- tion of sayings of Jesus. Especially the Synoptists represent him as teaching in the temple as well as on his way to and from that sanc- tuary. Those teachings consist of three groups. The first com- prises parables and sayings which are found in one Gospel only. The second contains discourses vouched tor by two oi the Gospels. The third belongs to all three. The first two groups may be put aside without any further examination because they do not form part of the common Synoptic source. -

When Jesus Threw Down the Gauntlet

WHEN JESUS THREW DOWN THE GAUNTLET. BY WM. WEBER. THE death of Jesus, whatever else it may be, is a very important event in the history of the human race. As such it forms a Hnk in the endless chain of cause and effect ; and we are obliged to ascertain, if possible, the facts which led up to the crucifixion and rendered it inevitable. The first question to be answered is : Who were the men that committed what has been called the greatest crime the world ever saw ? A parallel question asks : How did Jesus provoke the resent- ment of those people to such a degree that they shrank not even from judicial murder in order to get rid of him? The First Gospel denotes four times the persons who engineered the death of Jesus "the chief priests and the elders of the people." The first passage where that happens is connected with the account of the Cleansing of the Temple (Matt. xxi. 23.) The second treats of the meeting at which it was decided to put Jesus out of the way. ( Matt. xxvi. 3.) The third tells of the arrest of Jesus. (Matt. xxvi. 47.) The fourth relates how he was turned over to the tender mercies of Pontius Pilate. ( Matt, xx vii. 1 ) The expression is used, as . appears from this enurrieration, just at the critical stations on the road to Calvary and may be a symbol characteristic of the principal source of the passion of Jesus in Matthew. The corresponding term of the Second and Third Gospels is "the chief priests and the scribes" : but that is not used exclusively in all the parallels to the just quoted passages. -

Jesus in Film: Hollywood Perspectives on the Jewishness of Jesus

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 2 Issue 2 October 1998 Article 2 October 1998 Jesus in Film: Hollywood Perspectives on the Jewishness of Jesus Adele Reinhartz [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf Recommended Citation Reinhartz, Adele (1998) "Jesus in Film: Hollywood Perspectives on the Jewishness of Jesus," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 2 : Iss. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol2/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jesus in Film: Hollywood Perspectives on the Jewishness of Jesus Abstract The purpose of this article is to survey a number of Jesus movies with respect to the portrayal of Jesus' Jewishness. As a New Testament scholar, I am curious to see how these celluloid representations of Jesus compare to academic depictions. For this reason, I begin by presenting briefly three trends in current historical Jesus research that construct Jesus' Jewishness in different ways. As a Jewish New Testament scholar, however, my interest in this question is fuelled by a conviction that the cinematic representations of Jesus both reflect and also affect cultural perceptions of both Jesus and Judaism. My survey of the films will therefore also consider issues of reception, and specifically, the image of Jesus and Judaism that emerges from each. This article is available in Journal of Religion & Film: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol2/iss2/2 Reinhartz: Jesus in Film Jesus of Nazareth is arguably the most ubiquitous figure in western culture. -

The Function of the Double Love Command in Matthew 22:34-40

Andrews Uniwsity Seminary Studies, Spring 1998, Vol. 36, No. 1, 7-22 Copyright @ 1998 by Andrews University Press. THE FUNCTION OF THE DOUBLE LOVE COMMAND IN MATTHEW 22:34-40 OSCARS. BROOKS Golden Gate Seminary Mill Valley, CA 94941 Matthew used the pericope of the double love command, love to God and neighbor, to summarize Jesus' teachings, as well as the laws of Moses, and to continue to demonstrate Jesus' prowess as a teacher in the presence of his Pharisaic opponents. This article sets forth the reasons for his doing so as well as the method used to accomplish this. Parallels to Matt 22:34-40 are found in Mark 12:28-34 and Luke 10:25- 28. It is not necessary here to do a full analysis of these parallels nor to determine the exact tradition behind the Synoptics. This has been done by Furnish, Fuller, Hultgren, and numerous others.' 7he Setting of the Double Love Command The quotations of Deut 6:5 and Lev 19:18 are the nucleus of each of the commandments. Hultgren thinks these two commandments, introduced by "Jesus said," formed a "free floatingn dominical saying in the early tradition.' Matthew's setting for the saying follows Mark's order, which places it in Jerusalem during Jesus' last days and is preceeded and followed by the same stories. Matthew opened the story by noting that the Pharisees "came together" (22:34) "to test him." Unlike Mark and Luke, Matthew made this a confrontation between Jesus and the Pharisees. A lawyer (nomikos) addressed Jesus as a teacher and asked: "Which is the great commandment in the law (nornos)" (22:36)? Jesus quoted Deut 6:5: "You shall love the Lord your God," thus answering the lawyer's question. -

Harmony of the Gospels

Harmony of the Gospels INTRODUCTIONS TO JESUS CHRIST Date Event Location Matthew Mark Luke John (1) Luke’s Introduction 1:1-4 (2) Pre-incarnation Work of Christ 1:1-18 (3) Genealogy of Jesus Christ 1:1-17 3:23-38 BIRTH, INFANCY, AND ADOLESCENCE OF JESUS AND JOHN THE BAPTIST Date Event Location Matthew Mark Luke John 7BC (1) Announcement of Birth of John the Baptist Jerusalem (Temple) 1:5-25 7/6BC (2) Announcement of Jesus’ Birth to Mary Nazareth 1:26-38 6/5BC (3) Song of Elizabeth to Mary Hill Country of Judah 1:39-45 (4) Mary’s Song of Praise 1:46-56 c.5BC (5) Birth of John the Baptist, His Father’s Song Judea 1:57-80 5BC (6) Announcement of Jesus’ Birth to Joseph Nazareth 1:18-25 5-4BC (7) Birth of Jesus Christ Bethlehem 1:24,25 2:1-7 (8) Proclamation by the Angels Near Bethlehem 2:8-14 (9) The Shepherds Visit Bethlehem 2:15-20 (10) Jesus’ Circumcision Bethlehem 2:21 (11) Witness of Simeon & Anna Jerusalem 2:22-38 (12) Visit of the Magi Jerusalem & Bethlehem 2:1-12 (13) Escape to Egypt & Murder of Babies Bethlehem 2:13-18 (14) From Egypt to Nazareth with Jesus 2:19-23 2:39 Afterward (15) Childhood of Jesus Nazareth 2:40,51 7/8AD (16) 12 year old Jesus Visits the Temple Jerusalem 2:41-50 Afterward (17) Summary of Jesus’ Growth to Adulthood Nazareth 2:51,52 TRUTHS ABOUT JOHN THE BAPTIST Date Event Location Matthew Mark Luke John c.28-30AD (1) John’s Ministry Begins Judean Wilderness 3:1 1:1-4 3:1,2 1:19-28 (2) Man and Message 3:2-12 1:2-8 3:3-14 (3) His Picture of Jesus 3:11,12 1:7,8 3:15-18 1:26,27 (4) His Courage 14:4-12 3:19,20 BEGINNING -

1 a Brief Background to the Sermon on the Mount P. Alex Early, D.Int.St

A Brief Background to the Sermon on the Mount P. Alex Early, D.Int.St. Pastor of Preaching and Theology Redemption Church | Seattle, WA September 27, 2017 Introduction The Sermon on the Mount (SM) found in Matthew chapters 5-7 mark out some of the most well known verses in the entire Bible. Both those inside and outside of the church tend to be familiar with the more famous statements contained in the SM such as “Hallowed be thy name” (Matt. 6:9) or “judge not lest you be judged” (7:1). And yet, many are unaware that those phrases find their origin in Jesus of Nazareth. For example, eleven years ago (it would be shocking to see something more recent!) a Gallup poll indicated that 4 in 10 Americans (U.S.) knew that Jesus preached the Sermon on the Mount.1 The purpose of providing some background information to the SM is simply to equip the saints here at Redemption Church in your ongoing theological and spiritual development. St. Paul’s reflective words upon his ministry amongst the Colossian church ring as powerful as ever here in Seattle, Him we proclaim, warning everyone and teaching everyone with all wisdom, that we may present everyone mature in Christ (Col. 1:28). As followers of the Lord Jesus, our maturity in our understanding and application of the gospel matters tremendously. Swiss Reformed theologian, Karl Barth, who passed away in 1968, once wrote to a pastor who had contacted Barth about holding a conference for what the pastor referred to as “non-theologians.” 1 T.C. -

1 the Great Commission According to Matthew's Gospel Accompanied by Insights from the Life and Writings of William Carey With

1 The Great Commission According To Matthew’s Gospel Accompanied by Insights From The Life and Writings Of William Carey With the Goal of A Passionate Global Vision For Our Seminary Matthew 28:16-20 I. Acknowledge He Has All Power. 28:16-18 1) Worship Him. 28:17 2) Hear Him. 28:18 II. Obey His Authoritative Plan. 28:19-20 1) Make disciples by going. 28:19 2) Make disciples by baptizing. 28:19 3) Make disciples by teaching. 28:20 III. Trust His Amazing Promise. 28:20 1) He will be with you constantly. 2) He will be with you continually. 2 The Great Commission…William Carey…A Passionate Global Vision Matthew 28:16-20 Introduction: 1) He may have been the greatest missionary since the time of the apostles. He rightly deserves the honor of being known as “the father of the modern missions movement.” William Carey was born in 1761 and died in 1834. He left England in 1793 as a missionary to India. He would never return home again. He was poor with only a grammar school education, and yet he would translate the Bible into dozens of languages and dialects, and he established schools and mission stations all over India. I love Timothy George’s description of what he calls this “lone, little man.” His resume: education, minimal; degrees, none; savings, depleted; political influence, nil; references, a band of country preachers half a world away. What are his resources? A weapon: love; a desire: to bring the light of God into the darkness; a strategy: to proclaim by life, lips, and letters the unsearchable riches of Christ” (George, 93). -

The Sermon on the Mount. the Ethel M. Wood Lecture Delivered Before the University of London on 7 March 1961

Joachim Jeremias, The Sermon On The Mount. The Ethel M. Wood Lecture delivered before the University of London on 7 March 1961. London: The Athlone Press, 1961. Pbk. ISBN: 0485143127. pp.33. The Sermon on the Mount Joachim Jeremias D. Theol., Dr. Phil., D.D. Professor of the New Testament in the University of Göttingen The Ethel M. Wood Lecture delivered before the University of London on 7 March 1961 Originally published by The University of London, The Athlone Press Translated by Professor Norman Perrin, Dr.theol. Atlanta, Emory University CONTENTS 1. The Problem, 7 2. The Origins of the Sermon on the Mount, 16 3. The Sermon on the Mount as an Early Christian Catechism, 20 4. The Individual Sayings of Jesus, 24 5. Not Law, but Gospel, 32 Joachim Jeremias, The Sermon On The Mount. The Ethel M. Wood Lecture delivered before the University of London on 7 March 1961. London: The Athlone Press, 1961. Pbk. ISBN: 0485143127. pp.33. [p.7] The Sermon On The Mount 1. The Problem What is the meaning of the Sermon on the Mount? This is a profound question, and one which affects not only our preaching and teaching but also, when we really face up to it, the very roots of our existence. Since the very beginning of the Church it has been a question with which all Christians have had to grapple, not only the theologians among them, and in the course of the centuries a whole range of answers has been given to it. In what follows I propose to indicate and discuss the three most important of these answers. -

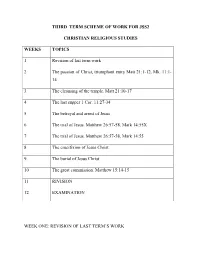

Third Term Jss 2 C

THIRD TERM SCHEME OF WORK FOR JSS2 CHRISTIAN RELIGIOUS STUDIES WEEKS TOPICS 1 Revision of last term work 2 The passion of Christ, triumphant entry Matt 21:1-12, Mk. 11:1- 14 3 The cleansing of the temple. Matt 21:10-17 4 The last supper 1 Cor. 11:27-34 5 The betrayal and arrest of Jesus 6 The trial of Jesus. Matthew 26:57-58, Mark 14:55X 7 The trial of Jesus. Matthew 26:57-58, Mark 14:55 8 The crucifixion of Jesus Christ 9. The burial of Jesus Christ 10 The great commission. Matthew 15:14-15 11 RIVISION 12 EXAMINATION WEEK ONE: REVISION OF LAST TERM’S WORK WEEK TWO TOPIC: THE PASSION OF CHRIST TRIUMPHANT ENTRY INTO JERUSALEM (THE PASSION) MARK 11:1- 11, MATTHEW 21:1-11 Jesus had started His earthly ministry for good three years. He has been going from one place to another preaching, teaching people about the kingdom of God. During the Passover festival celebration in Jerusalem, Jesus wanted to go down to Jerusalem. As He was going with His disciples, they passed through Samaria and entered Jericho. When they came near Jerusalem to Bethany at the mount of olive they stopped there and He sent out two of his disciples to Bethany to bring back to Him a colt of an ass which had never been driven by anyone. He told them if anyone should challenge them, their reply would be the Lord needed it. And after use, if would be sent back. They went and found the colt and they brought it to Jesus. -

The Meaning and Message of the Beatitudes in the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5-7) Ranko Stefanovic Andrews University

The Meaning and Message of the Beatitudes in the Sermon On the Mount (Matthew 5-7) Ranko Stefanovic Andrews University The Sermon on the Mount recorded in Matthew 5-7 is probably one of the best known of Jesus’ teachings recorded in the Gospels. This is the first of the five discourses in Matthew that Jesus delivered on an unnamed mount that has traditionally been located on the northwest shore of the Sea of Galilee near Capernaum, which is today marked by the Church of the Beatitudes. New Testament scholarship has treated the Sermon on the Mount as a collection of short sayings spoken by the historical Jesus on different occasions, which Matthew, in this view, redactionally put into one sermon.1 A similar version of the Sermon is found in Luke 6:20-49, known as the Sermon on the Plain, which has been commonly regarded as a Lucan variant of the same discourse. 2 The position taken in this paper is, first of all, that the Matthean and Lucan versions are two different sermons with similar content delivered by Jesus on two different occasions. 3 Secondly, it seems almost certain that the two discourses are summaries of much longer ones, each with a different emphasis, spiritual and physical respectively. Whatever position one takes, it appears that the Sermon on the Mount in Matthew is not just a collection of randomly selected pieces; the discourse displays one coherent literary theme. The Sermon is introduced with the Beatitudes, which are concluded with a couplet of short metaphoric parables on salt and light. -

Jesus' Intervention in the Temple

JETS 58/3 (2015) 545–69 JESUS’ INTERVENTION IN THE TEMPLE: ONCE OR TWICE? ALLAN CHAPPLE* The Gospel of John has Jesus intervening dramatically in the TemplE (John 2:13–22) before he bEgins his public ministry in Galilee (John 3:24; 4:3; cf. Mark 1:14). HowevEr, the only such event rEported in the Synoptics occurs at the end of Jesus’ ministry (Mark 11:15–18 and parallels). What are wE to makE of this discrep- ancy? Logically, there are four possible explanations: 1. The Synoptics are right about when the event took place—so that John has moved it to the beginning of the ministry, presumably for theological reasons. This is the view of the overwhelming majority. 2. John is right about when this happened—so the Synoptic Gospels have moved it to the end of Jesus’ ministry (again, presumably for theological reasons).1 3. NeithEr the Synoptics nor John have got it right, because no such event oc- curred.2 * Allan ChapplE is SEnior LEcturEr in NT at Trinity ThEological CollEgE, P.O. Box 115, LEEdErvillE, Perth, WA 6902, Australia. 1 SEE, E.g., Paul N. AndErson, The Fourth Gospel and the Quest for Jesus: Modern Foundations Reconsidered (LNTS 321; London: T&T Clark, 2006) 158–61; F.-M. Braun, “L’expulsion dEs vEndEurs du TemplE (Mt., xxi, 12–17, 23–27; Mc., xi, 15–19, 27–33; Lc., xix, 45–xx, 8; Jo., ii, 13–22),” RB 38 (1929) 188–91; R. A. Edwards, The Gospel according to St. John: Its Interpretation and Criticism (London: EyrE & SpottiswoodE, 1954) 37–38; A.