The Cleansing of the Temple in Four Jesus Films

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comedy Taken Seriously the Mafia’S Ties to a Murder

MONDAY Beauty and the Beast www.annistonstar.com/tv The series returns with an all-new episode that finds Vincent (Jay Ryan) being TVstar arrested for May 30 - June 5, 2014 murder. 8 p.m. on The CW TUESDAY Celebrity Wife Swap Rock prince Dweezil Zappa trades his mate for the spouse of a former MLB outfielder. 9 p.m. on ABC THURSDAY Elementary Watson (Lucy Liu) and Holmes launch an investigation into Comedy Taken Seriously the mafia’s ties to a murder. J.B. Smoove is the dynamic new host of NBC’s 9:01 p.m. on CBS standup comedy competition “Last Comic Standing,” airing Mondays at 7 p.m. Get the deal of a lifetime for Home Phone Service. * $ Cable ONE is #1 in customer satisfaction for home phone.* /mo Talk about value! $25 a month for life for Cable ONE Phone. Now you’ve got unlimited local calling and FREE 25 long distance in the continental U.S. All with no contract and a 30-Day Money-Back Guarantee. It’s the best FOR LIFE deal on the most reliable phone service. $25 a month for life. Don’t wait! 1-855-CABLE-ONE cableone.net *Limited Time Offer. Promotional rate quoted good for eligible residential New Customers. Existing customers may lose current discounts by subscribing to this offer. Changes to customer’s pre-existing services initiated by customer during the promotional period may void Phone offer discount. Offer cannot be combined with any other discounts or promotions and excludes taxes, fees and any equipment charges. -

Two Answers to the Challenge of Jesus

TWO ANSWERS TO THE CHALLENGE OF JESUS. HV w i i.i.i am WEBER. i < Continued) T1IF Cleansing of the Temple has a double aspect It was, on the one hand, an attack upon the chief priests and their allies, the scribes. On the other hand, it was a bold stroke for the re- ligions liberty of the people. From both sides there must have come an answer. His enemies could not simply ignore what happened. Unless they were ready to accept the Galilean as their master, they were compelled to think of ways and means by which to defeat him. At the same time, his friends and admirers would discuss his valiant deed and formulate certain conclusions as to his character and authority, the more so as the chief priests themselves had first broached that question in public. Thus we may expect a twofold answer to the challenge of Jesus provided the Gospels have pre-erved a complete account. The story of the Cleansing of the Temple is not continued at once. It is followed in all four Gospels by a rather copious collec- tion of sayings of Jesus. Especially the Synoptists represent him as teaching in the temple as well as on his way to and from that sanc- tuary. Those teachings consist of three groups. The first com- prises parables and sayings which are found in one Gospel only. The second contains discourses vouched tor by two oi the Gospels. The third belongs to all three. The first two groups may be put aside without any further examination because they do not form part of the common Synoptic source. -

When Jesus Threw Down the Gauntlet

WHEN JESUS THREW DOWN THE GAUNTLET. BY WM. WEBER. THE death of Jesus, whatever else it may be, is a very important event in the history of the human race. As such it forms a Hnk in the endless chain of cause and effect ; and we are obliged to ascertain, if possible, the facts which led up to the crucifixion and rendered it inevitable. The first question to be answered is : Who were the men that committed what has been called the greatest crime the world ever saw ? A parallel question asks : How did Jesus provoke the resent- ment of those people to such a degree that they shrank not even from judicial murder in order to get rid of him? The First Gospel denotes four times the persons who engineered the death of Jesus "the chief priests and the elders of the people." The first passage where that happens is connected with the account of the Cleansing of the Temple (Matt. xxi. 23.) The second treats of the meeting at which it was decided to put Jesus out of the way. ( Matt. xxvi. 3.) The third tells of the arrest of Jesus. (Matt. xxvi. 47.) The fourth relates how he was turned over to the tender mercies of Pontius Pilate. ( Matt, xx vii. 1 ) The expression is used, as . appears from this enurrieration, just at the critical stations on the road to Calvary and may be a symbol characteristic of the principal source of the passion of Jesus in Matthew. The corresponding term of the Second and Third Gospels is "the chief priests and the scribes" : but that is not used exclusively in all the parallels to the just quoted passages. -

Jesus in Film: Hollywood Perspectives on the Jewishness of Jesus

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 2 Issue 2 October 1998 Article 2 October 1998 Jesus in Film: Hollywood Perspectives on the Jewishness of Jesus Adele Reinhartz [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf Recommended Citation Reinhartz, Adele (1998) "Jesus in Film: Hollywood Perspectives on the Jewishness of Jesus," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 2 : Iss. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol2/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jesus in Film: Hollywood Perspectives on the Jewishness of Jesus Abstract The purpose of this article is to survey a number of Jesus movies with respect to the portrayal of Jesus' Jewishness. As a New Testament scholar, I am curious to see how these celluloid representations of Jesus compare to academic depictions. For this reason, I begin by presenting briefly three trends in current historical Jesus research that construct Jesus' Jewishness in different ways. As a Jewish New Testament scholar, however, my interest in this question is fuelled by a conviction that the cinematic representations of Jesus both reflect and also affect cultural perceptions of both Jesus and Judaism. My survey of the films will therefore also consider issues of reception, and specifically, the image of Jesus and Judaism that emerges from each. This article is available in Journal of Religion & Film: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol2/iss2/2 Reinhartz: Jesus in Film Jesus of Nazareth is arguably the most ubiquitous figure in western culture. -

Actual Malice in the Inter-American Court of Human Rights

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Faculty Publications 2013 Actual Malice in the Inter-American Court of Human Rights Edward L. Carter Brigham Young University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub Part of the Communication Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Carter, Edward L., "Actual Malice in the Inter-American Court of Human Rights" (2013). Faculty Publications. 4799. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub/4799 This Peer-Reviewed Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. ACTUAL MALICE IN THE INTER- AMERICAN COURT OF HUMAN RIGHTS EDWARD CARTER* The Inter-American Court of Human Rights decided four cases in recent years that represent a positive step for freedom of expression in nations that belong to the Organization of American States. In 2004 and again in 2008, the court stopped short of adopting a standard that would require proof of actual malice in criminal defamation cases brought by public officials. In 2009, however, the court seemed to adopt the actual malice rule without calling it that. The court’s progress toward actual malice is chronicled in this article. The article concludes that the court’s decision not to explicitly use the phrase “actual malice” may be a positive development for freedom of expression in the Americas. Since its inception in 1979, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, based in San José, Costa Rica, has moved to protect freedom of expression under the American Convention on Human Rights. -

Harmony of the Gospels

Harmony of the Gospels INTRODUCTIONS TO JESUS CHRIST Date Event Location Matthew Mark Luke John (1) Luke’s Introduction 1:1-4 (2) Pre-incarnation Work of Christ 1:1-18 (3) Genealogy of Jesus Christ 1:1-17 3:23-38 BIRTH, INFANCY, AND ADOLESCENCE OF JESUS AND JOHN THE BAPTIST Date Event Location Matthew Mark Luke John 7BC (1) Announcement of Birth of John the Baptist Jerusalem (Temple) 1:5-25 7/6BC (2) Announcement of Jesus’ Birth to Mary Nazareth 1:26-38 6/5BC (3) Song of Elizabeth to Mary Hill Country of Judah 1:39-45 (4) Mary’s Song of Praise 1:46-56 c.5BC (5) Birth of John the Baptist, His Father’s Song Judea 1:57-80 5BC (6) Announcement of Jesus’ Birth to Joseph Nazareth 1:18-25 5-4BC (7) Birth of Jesus Christ Bethlehem 1:24,25 2:1-7 (8) Proclamation by the Angels Near Bethlehem 2:8-14 (9) The Shepherds Visit Bethlehem 2:15-20 (10) Jesus’ Circumcision Bethlehem 2:21 (11) Witness of Simeon & Anna Jerusalem 2:22-38 (12) Visit of the Magi Jerusalem & Bethlehem 2:1-12 (13) Escape to Egypt & Murder of Babies Bethlehem 2:13-18 (14) From Egypt to Nazareth with Jesus 2:19-23 2:39 Afterward (15) Childhood of Jesus Nazareth 2:40,51 7/8AD (16) 12 year old Jesus Visits the Temple Jerusalem 2:41-50 Afterward (17) Summary of Jesus’ Growth to Adulthood Nazareth 2:51,52 TRUTHS ABOUT JOHN THE BAPTIST Date Event Location Matthew Mark Luke John c.28-30AD (1) John’s Ministry Begins Judean Wilderness 3:1 1:1-4 3:1,2 1:19-28 (2) Man and Message 3:2-12 1:2-8 3:3-14 (3) His Picture of Jesus 3:11,12 1:7,8 3:15-18 1:26,27 (4) His Courage 14:4-12 3:19,20 BEGINNING -

Guide to the Papers of the Capri Community Film Society

Capri Community Film Society Papers Guide to the Papers of the Capri Community Film Society Auburn University at Montgomery Archives and Special Collections © AUM Library Written By: Rickey Best & Jason Kneip Last Updated: 2/19/2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS Content Page # Collection Summary 2 Administrative Information 2 Restrictions 2-3 Index Terms 3 Agency History 3-4 1 of 64 Capri Community Film Society Papers Scope and Content 5 Arrangement 5-10 Inventory 10- Collection Summary Creator: Capri Community Film Society Title: Capri Community Film Society Papers Dates: 1983-present Quantity: 6 boxes; 6.0 cu. Ft. Identification: 92/2 Contact Information: AUM Library Archives & Special Collections P.O. Box 244023 Montgomery, AL 36124-4023 Ph: (334) 244-3213 Email: [email protected] Administrative Information Preferred Citation: Capri Community Film Society Papers, Auburn University Montgomery Library, Archives & Special Collections. Acquisition Information: The collection began with an initial transfer on September 19, 1991. A second donation occurred in February, 1995. Since then, regular donations of papers occur on a yearly basis. Processed By: Jermaine Carstarphen, Student Assistant & Rickey Best, Archivist/Special Collections Librarian (1993); Jason Kneip, Archives/Special Collections Librarian. Samantha McNeilly, Archives/Special Collections Assistant. 2 of 64 Capri Community Film Society Papers Restrictions Restrictions on access: Access to membership files is closed for 25 years from date of donation. Restrictions on usage: Researchers are responsible for addressing copyright issues on materials not in the public domain. Index Terms The material is indexed under the following headings in the Auburn University at Montgomery’s Library catalogs – online and offline. -

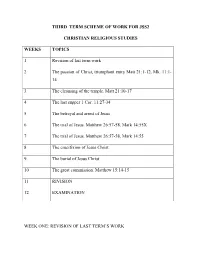

Third Term Jss 2 C

THIRD TERM SCHEME OF WORK FOR JSS2 CHRISTIAN RELIGIOUS STUDIES WEEKS TOPICS 1 Revision of last term work 2 The passion of Christ, triumphant entry Matt 21:1-12, Mk. 11:1- 14 3 The cleansing of the temple. Matt 21:10-17 4 The last supper 1 Cor. 11:27-34 5 The betrayal and arrest of Jesus 6 The trial of Jesus. Matthew 26:57-58, Mark 14:55X 7 The trial of Jesus. Matthew 26:57-58, Mark 14:55 8 The crucifixion of Jesus Christ 9. The burial of Jesus Christ 10 The great commission. Matthew 15:14-15 11 RIVISION 12 EXAMINATION WEEK ONE: REVISION OF LAST TERM’S WORK WEEK TWO TOPIC: THE PASSION OF CHRIST TRIUMPHANT ENTRY INTO JERUSALEM (THE PASSION) MARK 11:1- 11, MATTHEW 21:1-11 Jesus had started His earthly ministry for good three years. He has been going from one place to another preaching, teaching people about the kingdom of God. During the Passover festival celebration in Jerusalem, Jesus wanted to go down to Jerusalem. As He was going with His disciples, they passed through Samaria and entered Jericho. When they came near Jerusalem to Bethany at the mount of olive they stopped there and He sent out two of his disciples to Bethany to bring back to Him a colt of an ass which had never been driven by anyone. He told them if anyone should challenge them, their reply would be the Lord needed it. And after use, if would be sent back. They went and found the colt and they brought it to Jesus. -

Jesus' Intervention in the Temple

JETS 58/3 (2015) 545–69 JESUS’ INTERVENTION IN THE TEMPLE: ONCE OR TWICE? ALLAN CHAPPLE* The Gospel of John has Jesus intervening dramatically in the TemplE (John 2:13–22) before he bEgins his public ministry in Galilee (John 3:24; 4:3; cf. Mark 1:14). HowevEr, the only such event rEported in the Synoptics occurs at the end of Jesus’ ministry (Mark 11:15–18 and parallels). What are wE to makE of this discrep- ancy? Logically, there are four possible explanations: 1. The Synoptics are right about when the event took place—so that John has moved it to the beginning of the ministry, presumably for theological reasons. This is the view of the overwhelming majority. 2. John is right about when this happened—so the Synoptic Gospels have moved it to the end of Jesus’ ministry (again, presumably for theological reasons).1 3. NeithEr the Synoptics nor John have got it right, because no such event oc- curred.2 * Allan ChapplE is SEnior LEcturEr in NT at Trinity ThEological CollEgE, P.O. Box 115, LEEdErvillE, Perth, WA 6902, Australia. 1 SEE, E.g., Paul N. AndErson, The Fourth Gospel and the Quest for Jesus: Modern Foundations Reconsidered (LNTS 321; London: T&T Clark, 2006) 158–61; F.-M. Braun, “L’expulsion dEs vEndEurs du TemplE (Mt., xxi, 12–17, 23–27; Mc., xi, 15–19, 27–33; Lc., xix, 45–xx, 8; Jo., ii, 13–22),” RB 38 (1929) 188–91; R. A. Edwards, The Gospel according to St. John: Its Interpretation and Criticism (London: EyrE & SpottiswoodE, 1954) 37–38; A. -

The Last Temptation of Christ": a Case Study

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 1990 Christian public relations strategies and "The Last Temptation of Christ": A case study Donald Gene Beehler Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Christianity Commons, and the Public Relations and Advertising Commons Recommended Citation Beehler, Donald Gene, "Christian public relations strategies and "The Last Temptation of Christ": A case study" (1990). Theses Digitization Project. 513. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/513 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHRISTIAN PUBLIC RELATIONS STRATEGIES AND "THE LAST TEMPTATION OF CHRIST": A CASE STUDY A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies By Donald Gene Beehler March 1990 CHRISTIAN PUBLIC RELATIONS STRATEGIES AND "THE LAST TEMPTATION OF CHRIST": A CASE STUDY A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino By Donald Gene Beehler March 1990 Approved by: 1% / Di^^John^Kaj^Kayjf man^ Chair, Communication■ - DateDcftf Ma^ck IS /I 9 0 Dr. Fred M^and;^, Communication r. C rk Mo tad^ Management ABSTRACT The purpose of this project is to develop a public relations plan to improve comniunication among Christian groups and to help promote mutual understanding between the evangelical Christian community and the secular news media. -

Schedule at a Glance

SCHEDULE AT A GLANCE Thursday, September 24, 8:30 AM – 12:30 Friday, September 25, 1:00 PM – 5:00 PM PM 12:15 PM BONUS Lunch & Learn 8:30 AM Welcome & Opening Keynote: Can Session: Language as an Equalizer You Have Soul at Work? 1:00 PM Welcome Back & Transform Your 9:35 AM Stretch Break Day: Tips From a Professional Organizer 9:45 AM Test Your Professional Development Knowledge with The 1:45 PM Identifying and Communicating Mather Group Quality Survey Research 10:00 AM Ethical Listening: Do You Hear 2:30 PM Diversity, Equity & Inclusion: Drive What I Hear? to Action 10:30 AM LinkedIn and Lockdown: Tips to 3:30 PM Test Your Safety Knowledge (Win Elevate Your Profile Prizes) & Break with Chesapeake Employers 11:00 AM Meditation Break with Rebekah Insurance Kaba, Lovesol 4 PM Closing Keynote: Mission Possible: 11:15 AM The Last Temptation of Pandemic Lessons on Resilience From a Marketing: Doubling-Down on Your Disaster Veteran Brand & Storytelling 4:45 PM Wrap-up Celebration 12:00 PM Everybody TikTok Now: A Podcast About Podcasting & PR 12:30 PM Join us for a Quick Preview of Day 2 12:45 PM BONUS Lunch & Learn Sessions (pick 1) (A) Demystifying the APR (V) Running Virtual Meetings Join us in thanking these supporters for making this conference possible! Presenting Sponsor Experience Sponsor Design Team SESSION DESCRIPTIONS THURSDAY SESSIONS 8:30 AM CAN YOU HAVE SOUL AT WORK? (Opening Keynote) Jardena London, Business Agility Consultant, Founder of Souls@Work, Author & Blogger What was the moment when work first crushed your soul? What would work look like for you to have soul at work? What would it look like if your organization had soul? Souls@Work believes we spend way too much of our lives at work to allow it to be soulless. -

Jesus As Priest in the Gospels Nicholas Perrin

Jesus as Priest in the Gospels Nicholas Perrin Nicholas Perrin is the Franklin S. Dryness Chair of Biblical Studies at Wheaton Grad- uate School and the former Dean of Wheaton Graduate School at Wheaton College. He earned his PhD from Marquette University. Most recently, he is the author of Jesus the Priest (SPCK/Baker Academic, 2018) and will also be publishing The Kingdom of God (Zondervan) in early 2019. A husband and the father of two grown sons, Dr. Perrin is a teaching elder in the Presbyterian Church in America. To the extent that New Testament (NT) Theology is concerned to convey the theologies of the NT writings as these have been critically interpreted, the project by nature entails a good deal of interpretative retrieval, that is, an up-to-date recounting of standard arguments and familiar paradigms for understanding the discrete canonical texts. One such “familiar paradigm,” easily demonstrable from the past hundred years or so of scholarly literature, holds that the Epistle to the Hebrews is unique by virtue of its emphasis on Jesus’ priesthood. From here, especially if one prefers to date Hebrews after the destruction of the temple, it is a straightforward move to infer that the concept of Jesus’ priesthood was entirely a post-Easter theologoumenon, likely occasioned by the destruction of the Jerusalem temple, and almost certainly limited in importance so far as first-century Christian belief was concerned. Whatever factors “in front of” the biblical text may have helped pave the way for this recurring interpretative judgment (here one may think, for example, of the fierce anti-sacerdotal character of so much nineteenth- and twenti- eth-century Protestant theology), it almost certainly mistaken.