The Cleansing of the Temple in the Fourth Gospel As a Call to Action for Social Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Two Answers to the Challenge of Jesus

TWO ANSWERS TO THE CHALLENGE OF JESUS. HV w i i.i.i am WEBER. i < Continued) T1IF Cleansing of the Temple has a double aspect It was, on the one hand, an attack upon the chief priests and their allies, the scribes. On the other hand, it was a bold stroke for the re- ligions liberty of the people. From both sides there must have come an answer. His enemies could not simply ignore what happened. Unless they were ready to accept the Galilean as their master, they were compelled to think of ways and means by which to defeat him. At the same time, his friends and admirers would discuss his valiant deed and formulate certain conclusions as to his character and authority, the more so as the chief priests themselves had first broached that question in public. Thus we may expect a twofold answer to the challenge of Jesus provided the Gospels have pre-erved a complete account. The story of the Cleansing of the Temple is not continued at once. It is followed in all four Gospels by a rather copious collec- tion of sayings of Jesus. Especially the Synoptists represent him as teaching in the temple as well as on his way to and from that sanc- tuary. Those teachings consist of three groups. The first com- prises parables and sayings which are found in one Gospel only. The second contains discourses vouched tor by two oi the Gospels. The third belongs to all three. The first two groups may be put aside without any further examination because they do not form part of the common Synoptic source. -

Bimt Seminar Handout

Bringing the Bible to LifeSeminar Physical Settings of the Bible Seminar Topics Session I: Introduction - “Physical Settings of the Bible” Session II: “Connecting the Dots” - Geography of Israel Session III: Archaeology & the Bible Session IV: Life & Ministry of Jesus Session V: Jerusalem in the Old Testament Session VI: Jerusalem in the Days of Jesus Session VII: Manners & Customs of the Bible Goals & Objectives • To gain a new and exciting “3-D” perspective of the land of the Bible. • To begin understanding the “playing board” of the Bible. • To pursue the adventure of “connecting the dots” between the ancient world of the Bible and Scripture. • To appreciate the context of the stories of the Bible, including the life and ministry of Jesus. • To grow in our walk of faith with the God of redemptive history. 2 Bringing the Bible to Life Seminar About Biblical Israel Ministries & Tours Biblical Israel Ministries & Tours (BIMT) was created 25 years ago (originally called Biblical Israel Tours) out of a passion for leading people to a personalized study tour experience of Israel, the land of the Bible. The ministry expanded in 2016. BIMT is now a support-based evangelical support-based non-profit 501c3 tax-exempt ministry dedicated to helping people “connect the dots” between the context of the ancient world of the Bible and Scripture. The two-fold purpose of BIMT is: 1. Leading highly biblical study-discipleship tours to Israel and other lands of the Bible, and 2. Providing “Physical Settings of the Bible” teaching and discipleship training for churches and schools. It is our prayer that BIMT helps people to not only grow in a deeper understanding (e.g. -

Reconstructing Herod's Temple Mount in Jerusalem

Reconstructing Herod’s Temple Mount in Jerusalem By Kathleen RitmeyerLeen Ritmeyer Herod the Great—master builder! Despite his crimes and excesses, no one can doubt his prowess as a builder. One of his most imposing achievements was in Jerusalem. To feed his passion for grandeur, to immortalize his name and to attempt to win the loyalty of his sometimes restive Jewish subjects, Herod rebuilt the Temple (1 on the reconstruction drawing) in lavish fashion. But first he extended the existing platform—the Temple Mount—on which it was built, doubling its size. Herod ruled from 37 to 4 B.C. Scarcely a generation after the completion of this unparalleled building project,a the Romans ploughed the Temple Mount and built a temple to Jupiter on the site. Not a trace of Herod’s Temple was left. The mighty retaining walls of the Temple Mount, however, were deliberately left lying in ruins throughout the Roman (70–324 A.D.) and Byzantine (324–640 A.D.) periods—testimony to the destruction of the Jewish state. The Islamic period (640–1099) brought further eradication of Herod’s glory. Although the Omayyad caliphs (whose dynasty lasted from 633 to 750) repaired a large breach in the southern wall of the Temple Mount, the entire area of the Mount and its immediate surroundings was covered by an extensive new religio-political complex, built in part from Herodian ashlars that the Romans had toppled. Still later, the Crusaders (1099–1291) erected a city wall in the south that required blocking up the southern gates to the Temple Mount. -

A History of Money in Palestine: from the 1900S to the Present

A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Mitter, Sreemati. 2014. A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:12269876 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present A dissertation presented by Sreemati Mitter to The History Department in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts January 2014 © 2013 – Sreemati Mitter All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Roger Owen Sreemati Mitter A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present Abstract How does the condition of statelessness, which is usually thought of as a political problem, affect the economic and monetary lives of ordinary people? This dissertation addresses this question by examining the economic behavior of a stateless people, the Palestinians, over a hundred year period, from the last decades of Ottoman rule in the early 1900s to the present. Through this historical narrative, it investigates what happened to the financial and economic assets of ordinary Palestinians when they were either rendered stateless overnight (as happened in 1948) or when they suffered a gradual loss of sovereignty and control over their economic lives (as happened between the early 1900s to the 1930s, or again between 1967 and the present). -

When Jesus Threw Down the Gauntlet

WHEN JESUS THREW DOWN THE GAUNTLET. BY WM. WEBER. THE death of Jesus, whatever else it may be, is a very important event in the history of the human race. As such it forms a Hnk in the endless chain of cause and effect ; and we are obliged to ascertain, if possible, the facts which led up to the crucifixion and rendered it inevitable. The first question to be answered is : Who were the men that committed what has been called the greatest crime the world ever saw ? A parallel question asks : How did Jesus provoke the resent- ment of those people to such a degree that they shrank not even from judicial murder in order to get rid of him? The First Gospel denotes four times the persons who engineered the death of Jesus "the chief priests and the elders of the people." The first passage where that happens is connected with the account of the Cleansing of the Temple (Matt. xxi. 23.) The second treats of the meeting at which it was decided to put Jesus out of the way. ( Matt. xxvi. 3.) The third tells of the arrest of Jesus. (Matt. xxvi. 47.) The fourth relates how he was turned over to the tender mercies of Pontius Pilate. ( Matt, xx vii. 1 ) The expression is used, as . appears from this enurrieration, just at the critical stations on the road to Calvary and may be a symbol characteristic of the principal source of the passion of Jesus in Matthew. The corresponding term of the Second and Third Gospels is "the chief priests and the scribes" : but that is not used exclusively in all the parallels to the just quoted passages. -

Jesus in Film: Hollywood Perspectives on the Jewishness of Jesus

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 2 Issue 2 October 1998 Article 2 October 1998 Jesus in Film: Hollywood Perspectives on the Jewishness of Jesus Adele Reinhartz [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf Recommended Citation Reinhartz, Adele (1998) "Jesus in Film: Hollywood Perspectives on the Jewishness of Jesus," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 2 : Iss. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol2/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jesus in Film: Hollywood Perspectives on the Jewishness of Jesus Abstract The purpose of this article is to survey a number of Jesus movies with respect to the portrayal of Jesus' Jewishness. As a New Testament scholar, I am curious to see how these celluloid representations of Jesus compare to academic depictions. For this reason, I begin by presenting briefly three trends in current historical Jesus research that construct Jesus' Jewishness in different ways. As a Jewish New Testament scholar, however, my interest in this question is fuelled by a conviction that the cinematic representations of Jesus both reflect and also affect cultural perceptions of both Jesus and Judaism. My survey of the films will therefore also consider issues of reception, and specifically, the image of Jesus and Judaism that emerges from each. This article is available in Journal of Religion & Film: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol2/iss2/2 Reinhartz: Jesus in Film Jesus of Nazareth is arguably the most ubiquitous figure in western culture. -

Conclusion 60

Being Black, Being British, Being Ghanaian: Second Generation Ghanaians, Class, Identity, Ethnicity and Belonging Yvette Twumasi-Ankrah UCL PhD 1 Declaration I, Yvette Twumasi-Ankrah confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 Table of Contents Declaration 2 List of Tables 8 Abstract 9 Impact statement 10 Acknowledgements 12 Chapter 1 - Introduction 13 Ghanaians in the UK 16 Ghanaian Migration and Settlement 19 Class, status and race 21 Overview of the thesis 22 Key questions 22 Key Terminology 22 Summary of the chapters 24 Chapter 2 - Literature Review 27 The Second Generation – Introduction 27 The Second Generation 28 The second generation and multiculturalism 31 Black and British 34 Second Generation – European 38 US Studies – ethnicity, labels and identity 40 Symbolic ethnicity and class 46 Ghanaian second generation 51 Transnationalism 52 Second Generation Return migration 56 Conclusion 60 3 Chapter 3 – Theoretical concepts 62 Background and concepts 62 Class and Bourdieu: field, habitus and capital 64 Habitus and cultural capital 66 A critique of Bourdieu 70 Class Matters – The Great British Class Survey 71 The Middle-Class in Ghana 73 Racism(s) – old and new 77 Black identity 83 Diaspora theory and the African diaspora 84 The creation of Black identity 86 Black British Identity 93 Intersectionality 95 Conclusion 98 Chapter 4 – Methodology 100 Introduction 100 Method 101 Focus of study and framework(s) 103 -

Harmony of the Gospels

Harmony of the Gospels INTRODUCTIONS TO JESUS CHRIST Date Event Location Matthew Mark Luke John (1) Luke’s Introduction 1:1-4 (2) Pre-incarnation Work of Christ 1:1-18 (3) Genealogy of Jesus Christ 1:1-17 3:23-38 BIRTH, INFANCY, AND ADOLESCENCE OF JESUS AND JOHN THE BAPTIST Date Event Location Matthew Mark Luke John 7BC (1) Announcement of Birth of John the Baptist Jerusalem (Temple) 1:5-25 7/6BC (2) Announcement of Jesus’ Birth to Mary Nazareth 1:26-38 6/5BC (3) Song of Elizabeth to Mary Hill Country of Judah 1:39-45 (4) Mary’s Song of Praise 1:46-56 c.5BC (5) Birth of John the Baptist, His Father’s Song Judea 1:57-80 5BC (6) Announcement of Jesus’ Birth to Joseph Nazareth 1:18-25 5-4BC (7) Birth of Jesus Christ Bethlehem 1:24,25 2:1-7 (8) Proclamation by the Angels Near Bethlehem 2:8-14 (9) The Shepherds Visit Bethlehem 2:15-20 (10) Jesus’ Circumcision Bethlehem 2:21 (11) Witness of Simeon & Anna Jerusalem 2:22-38 (12) Visit of the Magi Jerusalem & Bethlehem 2:1-12 (13) Escape to Egypt & Murder of Babies Bethlehem 2:13-18 (14) From Egypt to Nazareth with Jesus 2:19-23 2:39 Afterward (15) Childhood of Jesus Nazareth 2:40,51 7/8AD (16) 12 year old Jesus Visits the Temple Jerusalem 2:41-50 Afterward (17) Summary of Jesus’ Growth to Adulthood Nazareth 2:51,52 TRUTHS ABOUT JOHN THE BAPTIST Date Event Location Matthew Mark Luke John c.28-30AD (1) John’s Ministry Begins Judean Wilderness 3:1 1:1-4 3:1,2 1:19-28 (2) Man and Message 3:2-12 1:2-8 3:3-14 (3) His Picture of Jesus 3:11,12 1:7,8 3:15-18 1:26,27 (4) His Courage 14:4-12 3:19,20 BEGINNING -

Crossroads 360 Virtual Tour Script Edited

Crossroads of Civilization Virtual Tour Script Note: Highlighted text signifies content that is only accessible on the 360 Tour. Welcome to Crossroads of Civilization. We divided this exhibit not by time or culture, but rather by traits that are shared by all civilizations. Watch this video to learn more about the making of Crossroads and its themes. Entrance Crossroads of Civilization: Ancient Worlds of the Near East and Mediterranean Crossroads of Civilization looks at the world's earliest major societies. Beginning more than 5,000 years ago in Egypt and the Near East, the exhibit traces their developments, offshoots, and spread over nearly four millennia. Interactive timelines and a large-scale digital map highlight the ebb and flow of ancient cultures, from Egypt and the earliest Mesopotamian kingdoms of the Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians, to the vast Persian, Hellenistic, and finally Roman empires, the latter eventually encompassing the entire Mediterranean region. Against this backdrop of momentous historical change, items from the Museum's collections are showcased within broad themes. Popular elements from classic exhibits of former years, such as our Greek hoplite warrior and Egyptian temple model, stand alongside newly created life-size figures, including a recreation of King Tut in his chariot. The latest research on our two Egyptian mummies features forensic reconstructions of the individuals in life. This truly was a "crossroads" of cultural interaction, where Asian, African, and European peoples came together in a massive blending of ideas and technologies. Special thanks to the following for their expertise: ● Dr. Jonathan Elias - Historical and maps research, CT interpretation ● Dr. -

Hybrid Identities of Buraku Outcastes in Japan

Educating Minds and Hearts to Change the World A publication of the University of San Francisco Center for the Volume IX ∙ Number 2 June ∙ 2010 Pacific Rim Copyright 2010 The Sea Otter Islands: Geopolitics and Environment in the East Asian Fur Trade >>..............................................................Richard Ravalli 27 Editors Joaquin Gonzalez John Nelson Shadows of Modernity: Hybrid Identities of Buraku Outcastes in Japan Editorial >>...............................................................Nicholas Mucks 36 Consultants Barbara K. Bundy East Timor and the Power of International Commitments in the American Hartmut Fischer Patrick L. Hatcher Decision Making Process >>.......................................................Christopher R. Cook 43 Editorial Board Uldis Kruze Man-lui Lau Syed Hussein Alatas: His Life and Critiques of the Malaysian New Economic Mark Mir Policy Noriko Nagata Stephen Roddy >>................................................................Choon-Yin Sam 55 Kyoko Suda Bruce Wydick Betel Nut Culture in Contemporary Taiwan >>..........................................................................Annie Liu 63 A Note from the Publisher >>..............................................Center for the Pacific Rim 69 Asia Pacific: Perspectives Asia Pacific: Perspectives is a peer-reviewed journal published at least once a year, usually in April/May. It Center for the Pacific Rim welcomes submissions from all fields of the social sciences and the humanities with relevance to the Asia Pacific 2130 Fulton St, LM280 region.* In keeping with the Jesuit traditions of the University of San Francisco, Asia Pacific: Perspectives com- San Francisco, CA mits itself to the highest standards of learning and scholarship. 94117-1080 Our task is to inform public opinion by a broad hospitality to divergent views and ideas that promote cross-cul- Tel: (415) 422-6357 Fax: (415) 422-5933 tural understanding, tolerance, and the dissemination of knowledge unreservedly. -

The Temple Mount in the Herodian Period (37 BC–70 A.D.)

The Temple Mount in the Herodian Period (37 BC–70 A.D.) Leen Ritmeyer • 08/03/2018 This post was originally published on Leen Ritmeyer’s website Ritmeyer Archaeological Design. It has been republished with permission. Visit the website to learn more about the history of the Temple Mount and follow Ritmeyer Archaeological Design on Facebook. Following on from our previous drawing, the Temple Mount during the Hellenistic and Hasmonean periods, we now examine the Temple Mount during the Herodian period. This was, of course, the Temple that is mentioned in the New Testament. Herod extended the Hasmonean Temple Mount in three directions: north, west and south. At the northwest corner he built the Antonia Fortress and in the south, the magnificent Royal Stoa. In 19 B.C. the master-builder, King Herod the Great, began the most ambitious building project of his life—the rebuilding of the Temple and the Temple Mount in lavish style. To facilitate this, he undertook a further expansion of the Hasmonean Temple Mount by extending it on three sides, to the north, west and south. Today’s Temple Mount boundaries still reflect this enlargement. The cutaway drawing below allows us to recap on the development of the Temple Mount so far: King Solomon built the First Temple on the top of Mount Moriah which is visible in the center of this drawing. This mountain top can be seen today, inside the Islamic Dome of the Rock. King Hezekiah built a square Temple Mount (yellow walls) around the site of the Temple, which he also renewed. -

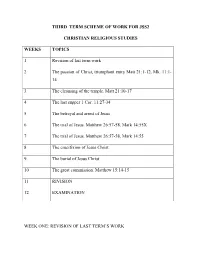

Third Term Jss 2 C

THIRD TERM SCHEME OF WORK FOR JSS2 CHRISTIAN RELIGIOUS STUDIES WEEKS TOPICS 1 Revision of last term work 2 The passion of Christ, triumphant entry Matt 21:1-12, Mk. 11:1- 14 3 The cleansing of the temple. Matt 21:10-17 4 The last supper 1 Cor. 11:27-34 5 The betrayal and arrest of Jesus 6 The trial of Jesus. Matthew 26:57-58, Mark 14:55X 7 The trial of Jesus. Matthew 26:57-58, Mark 14:55 8 The crucifixion of Jesus Christ 9. The burial of Jesus Christ 10 The great commission. Matthew 15:14-15 11 RIVISION 12 EXAMINATION WEEK ONE: REVISION OF LAST TERM’S WORK WEEK TWO TOPIC: THE PASSION OF CHRIST TRIUMPHANT ENTRY INTO JERUSALEM (THE PASSION) MARK 11:1- 11, MATTHEW 21:1-11 Jesus had started His earthly ministry for good three years. He has been going from one place to another preaching, teaching people about the kingdom of God. During the Passover festival celebration in Jerusalem, Jesus wanted to go down to Jerusalem. As He was going with His disciples, they passed through Samaria and entered Jericho. When they came near Jerusalem to Bethany at the mount of olive they stopped there and He sent out two of his disciples to Bethany to bring back to Him a colt of an ass which had never been driven by anyone. He told them if anyone should challenge them, their reply would be the Lord needed it. And after use, if would be sent back. They went and found the colt and they brought it to Jesus.