The Temple Mount in the Herodian Period (37 BC–70 A.D.)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bimt Seminar Handout

Bringing the Bible to LifeSeminar Physical Settings of the Bible Seminar Topics Session I: Introduction - “Physical Settings of the Bible” Session II: “Connecting the Dots” - Geography of Israel Session III: Archaeology & the Bible Session IV: Life & Ministry of Jesus Session V: Jerusalem in the Old Testament Session VI: Jerusalem in the Days of Jesus Session VII: Manners & Customs of the Bible Goals & Objectives • To gain a new and exciting “3-D” perspective of the land of the Bible. • To begin understanding the “playing board” of the Bible. • To pursue the adventure of “connecting the dots” between the ancient world of the Bible and Scripture. • To appreciate the context of the stories of the Bible, including the life and ministry of Jesus. • To grow in our walk of faith with the God of redemptive history. 2 Bringing the Bible to Life Seminar About Biblical Israel Ministries & Tours Biblical Israel Ministries & Tours (BIMT) was created 25 years ago (originally called Biblical Israel Tours) out of a passion for leading people to a personalized study tour experience of Israel, the land of the Bible. The ministry expanded in 2016. BIMT is now a support-based evangelical support-based non-profit 501c3 tax-exempt ministry dedicated to helping people “connect the dots” between the context of the ancient world of the Bible and Scripture. The two-fold purpose of BIMT is: 1. Leading highly biblical study-discipleship tours to Israel and other lands of the Bible, and 2. Providing “Physical Settings of the Bible” teaching and discipleship training for churches and schools. It is our prayer that BIMT helps people to not only grow in a deeper understanding (e.g. -

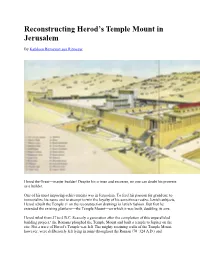

Reconstructing Herod's Temple Mount in Jerusalem

Reconstructing Herod’s Temple Mount in Jerusalem By Kathleen RitmeyerLeen Ritmeyer Herod the Great—master builder! Despite his crimes and excesses, no one can doubt his prowess as a builder. One of his most imposing achievements was in Jerusalem. To feed his passion for grandeur, to immortalize his name and to attempt to win the loyalty of his sometimes restive Jewish subjects, Herod rebuilt the Temple (1 on the reconstruction drawing) in lavish fashion. But first he extended the existing platform—the Temple Mount—on which it was built, doubling its size. Herod ruled from 37 to 4 B.C. Scarcely a generation after the completion of this unparalleled building project,a the Romans ploughed the Temple Mount and built a temple to Jupiter on the site. Not a trace of Herod’s Temple was left. The mighty retaining walls of the Temple Mount, however, were deliberately left lying in ruins throughout the Roman (70–324 A.D.) and Byzantine (324–640 A.D.) periods—testimony to the destruction of the Jewish state. The Islamic period (640–1099) brought further eradication of Herod’s glory. Although the Omayyad caliphs (whose dynasty lasted from 633 to 750) repaired a large breach in the southern wall of the Temple Mount, the entire area of the Mount and its immediate surroundings was covered by an extensive new religio-political complex, built in part from Herodian ashlars that the Romans had toppled. Still later, the Crusaders (1099–1291) erected a city wall in the south that required blocking up the southern gates to the Temple Mount. -

Israel and Judah: 18. Temple Interior and Dedication

Associates for Scriptural Knowledge • P.O. Box 25000, Portland, OR 97298-0990 USA © ASK, March 2019 • All rights reserved • Number 3/19 Telephone: 503 292 4352 • Internet: www.askelm.com • E-Mail: [email protected] How the Siege of Titus Locates the Temple Mount in the City of David by Marilyn Sams, July 2016 Formatted and annotated by David Sielaff, March 2019 This detailed research paper by independent author Marilyn Sams is one of several to follow her 2015 book, The Jerusalem Temple Mount Myth. Her book was inspired by a desire to prove (or disprove) Dr. Ernest Martin’s research in The Temples That Jerusalem Forgot. Ms. Sams wrote a second book in 2017, The Jerusalem Temple Mount: A Compendium of Ancient Descriptions expanding the argument in her first book, itemizing and analyzing 375 ancient descriptions of the Temple, Fort Antonia, and environs, all confirming a Gihon location for God’s Temples.1 Her books and articles greatly advance Dr. Martin’s arguments. David Sielaff, ASK Editor Marilyn Sams: The siege of Titus has been the subject of many books and papers, but always from the false perspective of the Jerusalem Temple Mount’s misidentification.2 The purpose of this paper is to illuminate additional aspects of the siege, in order to show how they cannot reasonably be applied to the current models of the temple and Fort Antonia, but can when the “Temple Mount” is identified as Fort Antonia. Conflicts Between the Rebellious Leaders Prior to the Siege of Titus A clarification of the definition of “Acra” is crucial to understanding the conflicts between John of Gischala and Simon of Giora, two of the rebellious [Jewish] faction leaders, who divided parts of Jerusalem 1 Her second book shows the impossibility of the so-called “Temple Mount” and demonstrate the necessity of a Gihon site of the Temples. -

Jerusalem Chronology 2015 January Jan. 1: the Israeli Supreme Court

Jerusalem Chronology 2015 January Jan. 1: The Israeli Supreme Court rejects an appeal to prevent the demolition of the homes of four Palestinians from East Jerusalem who attacked Israelis in West Jerusalem in recent months. - Marabouts at Al-Aqsa Mosque confront a group of settlers touring Al-Aqsa compound. Jan. 3: Palestinian MK Ahmad Tibi joins hundreds of Palestinians marching toward the Al-Aqsa Mosque in the Old City of Jerusalem to mark the Prophet Muhammad's birthday. Jan. 5: Settlers tour Al-Aqsa Mosque compound while Israeli forces confiscate the IDs of Muslims trying to enter. - Around 50 Israeli forces along with 18 settlers tour Al-Aqsa compound. Jan. 8: A Jewish Israeli man is stabbed and injured by an unknown assailant while walking near the Old City’s Damascus Gate. Jan. 9: Israeli police detain at least seven Palestinians in a series of raids in the Old City over the stabbing a day earlier. - Yedioth Ahronoth reports that the Israeli Intelligence (Shabak) frustrated an operation that was intended to blow the Dome of the Rock by an American immigrant. Jan. 11: Israeli police forces detain seven Palestinians from Silwan after a settler vehicle was torched in the area. Jan. 12: A Jerusalem magistrate court has ruled that Israeli settlers who occupied Palestinian homes in East Jerusalem may not make substantial changes to the properties. - Settlers tour Al-Aqsa Mosque compound. Jan. 13: Israeli forces detained three 14-year old youth during a raid on Issawiyya and two women while leaving Al-Aqsa Mosque. Jan. 14: Jewish extremists morning punctured the tires of 11 vehicles in Beit Safafa. -

Crossroads 360 Virtual Tour Script Edited

Crossroads of Civilization Virtual Tour Script Note: Highlighted text signifies content that is only accessible on the 360 Tour. Welcome to Crossroads of Civilization. We divided this exhibit not by time or culture, but rather by traits that are shared by all civilizations. Watch this video to learn more about the making of Crossroads and its themes. Entrance Crossroads of Civilization: Ancient Worlds of the Near East and Mediterranean Crossroads of Civilization looks at the world's earliest major societies. Beginning more than 5,000 years ago in Egypt and the Near East, the exhibit traces their developments, offshoots, and spread over nearly four millennia. Interactive timelines and a large-scale digital map highlight the ebb and flow of ancient cultures, from Egypt and the earliest Mesopotamian kingdoms of the Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians, to the vast Persian, Hellenistic, and finally Roman empires, the latter eventually encompassing the entire Mediterranean region. Against this backdrop of momentous historical change, items from the Museum's collections are showcased within broad themes. Popular elements from classic exhibits of former years, such as our Greek hoplite warrior and Egyptian temple model, stand alongside newly created life-size figures, including a recreation of King Tut in his chariot. The latest research on our two Egyptian mummies features forensic reconstructions of the individuals in life. This truly was a "crossroads" of cultural interaction, where Asian, African, and European peoples came together in a massive blending of ideas and technologies. Special thanks to the following for their expertise: ● Dr. Jonathan Elias - Historical and maps research, CT interpretation ● Dr. -

The Hashemite Custodianship of Jerusalem's Islamic and Christian

THE HASHEMITE CUSTODIANSHIP OF JERUSALEM’S ISLAMIC AND CHRISTIAN HOLY SITES 1917–2020 CE White Paper The Royal Aal Al-Bayt Institute for Islamic Thought THE HASHEMITE CUSTODIANSHIP OF JERUSALEM’S ISLAMIC AND CHRISTIAN HOLY SITES 1917–2020 CE White Paper The Royal Aal Al-Bayt Institute for Islamic Thought THE HASHEMITE CUSTODIANSHIP OF JERUSALEM’S ISLAMIC AND CHRISTIAN HOLY SITES 1917–2020 CE Copyright © 2020 by The Royal Aal Al-Bayt Institute for Islamic Thought All rights reserved. No part of this document may be used or reproduced in any manner wthout the prior consent of the publisher. Cover Image: Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem © Shutterstock Title Page Image: Dome of the Rock and Jerusalem © Shutterstock isbn 978–9957–635–47–3 Printed in Jordan by The National Press Third print run CONTENTS ABSTRACT 5 INTRODUCTION: THE HASHEMITE CUSTODIANSHIP OF THE HOLY SITES IN JERUSALEM 7 PART ONE: THE ARAB, JEWISH, CHRISTIAN AND ISLAMIC HISTORY OF JERUSALEM IN BRIEF 9 PART TWO: THE CUSTODIANSHIP OF THE ISLAMIC HOLY SITES IN JERUSALEM 23 I. The Religious Significance of Jerusalem and its Holy Sites to Muslims 25 II. What is Meant by the ‘Islamic Holy Sites’ of Jerusalem? 30 III. The Significance of the Custodianship of Jerusalem’s Islamic Holy Sites 32 IV. The History of the Hashemite Custodianship of Jerusalem’s Islamic Holy Sites 33 V. The Functions of the Custodianship of Jerusalem’s Islamic Holy Sites 44 VI. Termination of the Islamic Custodianship 53 PART THREE: THE CUSTODIANSHIP OF THE CHRISTIAN HOLY SITES IN JERUSALEM 55 I. The Religious Significance of Jerusalem and its Holy Sites to Christians 57 II. -

Boundaries, Barriers, Walls

1 Boundaries, Barriers, Walls Jerusalem’s unique landscape generates a vibrant interplay between natural and built features where continuity and segmentation align with the complexity and volubility that have characterized most of the city’s history. The softness of its hilly contours and the harmony of the gentle colors stand in contrast with its boundar- ies, which serve to define, separate, and segregate buildings, quarters, people, and nations. The Ottoman city walls (seefigure )2 separate the old from the new; the Barrier Wall (see figure 3), Israelis from Palestinians.1 The former serves as a visual reminder of the past, the latter as a concrete expression of the current political conflict. This chapter seeks to examine and better understand the physical realities of the present: how they reflect the past, and how the ancient material remains stimulate memory, conscious knowledge, and unconscious perception. The his- tory of Jerusalem, as it unfolds in its physical forms and multiple temporalities, brings to the surface periods of flourish and decline, of creation and destruction. TOPOGRAPHY AND GEOGRAPHY The topographical features of Jerusalem’s Old City have remained relatively con- stant since antiquity (see figure ).4 Other than the Central Valley (from the time of the first-century historian Josephus also known as the Tyropoeon Valley), which has been largely leveled and developed, most of the city’s elevations, protrusions, and declivities have maintained their approximate proportions from the time the city was first settled. In contrast, the urban fabric and its boundaries have shifted constantly, adjusting to ever-changing demographic, socioeconomic, and political conditions.2 15 Figure 2. -

The Walls of Jerusalem

Palestine Exploration Quarterly ISSN: 0031-0328 (Print) 1743-1301 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ypeq20 The Walls of Jerusalem C. W. Wilson To cite this article: C. W. Wilson (1905) The Walls of Jerusalem, Palestine Exploration Quarterly, 37:3, 231-243, DOI: 10.1179/peq.1905.37.3.231 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1179/peq.1905.37.3.231 Published online: 20 Nov 2013. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 13 View related articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ypeq20 Download by: [UNSW Library] Date: 23 April 2016, At: 06:55 231 THE 'VALLS OF JERUSALEM. By Major-Gen. Sir C. W. WILSON, K.C.B., l).C.L., F.R.S. 1. General Remarks; 2. The City Walls in A.D. 70. 1. Gene"'alRernarks.-Before attempting to investigate the questions connected with the ancient walls of Jerusalem, some consideration of the general principles that governed the construction of fortifica- tions in early times is not only desirable, but necessary. Jerusalem was strongly fortified at all periods of its· history, but there is .no reason to suppose that there was anything unusual in the trace and construction of its walls. The defences of Jebus could not have differed greatly from those of other Canaanite cities; the walls of David and his successors, which Nehemiah restored, ,vere constructed probably in accordance with Phrenician systems of fortification; and the citadels and ,valls built ·by Herod the Great and Herod Agrippa were almost certainly Greek or Greco-Roman in character. -

Day 7 Thursday March 10, 2022 Temple Mount Western Wall (Wailing Wall) Temple Institute Jewish Quarter Quarter Café Wohl Museu

Day 7 Thursday March 10, 2022 Temple Mount Western Wall (Wailing Wall) Temple Institute Jewish Quarter Quarter Café Wohl Museum Tower of David Herod’s Palace Temple Mount The Temple Mount, in Hebrew: Har HaBáyit, "Mount of the House of God", known to Muslims as the Haram esh-Sharif, "the Noble Sanctuary and the Al Aqsa Compound, is a hill located in the Old City of Jerusalem that for thousands of years has been venerated as a holy site in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam alike. The present site is a flat plaza surrounded by retaining walls (including the Western Wall) which was built during the reign of Herod the Great for an expansion of the temple. The plaza is dominated by three monumental structures from the early Umayyad period: the al-Aqsa Mosque, the Dome of the Rock and the Dome of the Chain, as well as four minarets. Herodian walls and gates, with additions from the late Byzantine and early Islamic periods, cut through the flanks of the Mount. Currently it can be reached through eleven gates, ten reserved for Muslims and one for non-Muslims, with guard posts of Israeli police in the vicinity of each. According to Jewish tradition and scripture, the First Temple was built by King Solomon the son of King David in 957 BCE and destroyed by the Neo-Babylonian Empire in 586 BCE – however no substantial archaeological evidence has verified this. The Second Temple was constructed under the auspices of Zerubbabel in 516 BCE and destroyed by the Roman Empire in 70 CE. -

A Guide to Al-Aqsa Mosque Al-Haram Ash-Sharif Contents

A Guide to Al-Aqsa Mosque Al-Haram Ash-Sharif Contents In the name of Allah, most compassionate, most merciful Introduction JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ<<<<3 Dear Visitor, Mosques JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ<<<<<4 Welcome to one of the major Islamic sacred sites and landmarks Domes JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ<<<24 of civilization in Jerusalem, which is considered a holy city in Islam because it is the city of the prophets. They preached of the Minarets JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ<<<30 Messenger of God, Prophet Mohammad (PBUH): Arched Gates JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ<<<32 The Messenger has believed in what was revealed to him from his Lord, and [so have] the believers. All of them have believed in Allah and His angels and Schools JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ<<<36 His books and His messengers, [saying], “We make no distinction between any of His messengers.” And they say, “We hear and we obey. [We seek] Your Corridors JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ<<<<44 forgiveness, our Lord, and to You is the [final] destination” (Qur’an 2:285). Gates JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ<<<<46 It is also the place where one of Prophet Mohammad’s miracles, the Night Journey (Al-Isra’ wa Al-Mi’raj), took place: Water Sources JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ<<<54 Exalted is He who took His Servant -

Pinpointing the Origins of Jerusalem's Temple Mount 3 June 2020

Pinpointing the origins of Jerusalem's Temple Mount 3 June 2020 as a historical reliance on using material culture findings like coins or texts to estimate dates of specific monuments. In this study, Regev and colleagues focused on pinpointing the specific construction dates for Wilson's Arch, an arch of "The Great Causeway", an ancient bridge linking Jerusalem's Temple Mount to the houses of Jerusalem's upper city, and which was excavated in 2015-2019 as part of a tourist development project. Wilson's Arch has been the subject of much scholarly debate, with construction dates suggested from the time of Herod the Great, Roman colonization, or even the Wilson's Arch excavation area.(A) Map of the old city of early Islamic period in Jerusalem (a span of about Jerusalem and the location Wilson's Arch. Copyrights: 700 years). Israel Antiquities Authority, 2020. (B) An artistic reconstruction of the Temple Mount in the time of Herod To better understand the specific timing of Wilson's the Great (1st century AD). The arrow points to the arch Arch (and the historical context in which it was known today as Wilson's Arch. Copyrights: Ritmeyer Archaeological Design, 2020. (C,D) Photographs of the constructed), Regev and colleagues used an site. The scale bar in D is 1 meter in length. (E,F) A 3D integrative approach in the field during its reconstruction of the site. As the site is under constant excavation, conducting radiocarbon dating of 33 renovations, a model is used here to illustrate the construction material samples directly at the site location of the various features and strata. -

Underground Jerusalem: the Excavation Of

Underground Jerusalem The excavation of tunnels, channels, and underground spaces in the Historic Basin 2015 >> Introduction >> Underground excavation in Jerusalem: From the middle of the 19th century to the Six Day War >> Tunnel excavations following the Six Day War >> Tunnel excavations under archaeological auspices >> Ancient underground complexes >> Underground tunnels >> Tunnel excavations as narrative >> Summary and conclusions >> Maps >> Endnotes Emek Shaveh (cc) | Email: [email protected] | website www.alt-arch.org Emek Shaveh is an organization of archaeologists and heritage professionals focusing on the role of tangible cultural heritage in Israeli society and in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. We view archaeology as a resource for strengthening understanding between different peoples and cultures. September 2015 Introduction Underground excavation in Jerusalem: From the middle of the The majority of the area of the Old City is densely built. As a result, there are very few nineteenth century until the Six Day War open spaces in which archaeological excavations can be undertaken. From a professional The intensive interest in channels, underground passages, and tunnels, ancient and modern, standpoint, this situation obligates the responsible authorities to restrict the number of goes back one 150 years. At that time the first European archaeologists in Jerusalem, aided excavations and to focus their attention on preserving and reinforcing existing structures. by local workers, dug deep into the heart of the Holy City in order to understand its ancient However, the political interests that aspire to establish an Israeli presence throughout the topography and the nature of the structures closest to the Temple Mount. Old City, including underneath the Muslim Quarter and in the nearby Palestinian village The British scholar Charles Warren was the first and most important of those who excavated of Silwan, have fostered the decision that intensive underground excavations must be underground Jerusalem.