Martin Boykan Elegy, String Quartet No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 2001, Tanglewood

SEMI OIAWA MUSIC DIRECTOR BERNARD HAITINK PRINCIPAL GUEST CONDUCTOR • i DALE CHIHULY INSTALLATIONS AND SCULPTURE / "^ik \ *t HOLSTEN GALLERIES CONTEMPORARY GLASS SCULPTURE ELM STREET, STOCKBRIDGE, MA 01262 . ( 41 3.298.3044 www. holstenga I leries * Save up to 70% off retail everyday! Allen-Edmoi. Nick Hilton C Baccarat Brooks Brothers msSPiSNEff3svS^:-A Coach ' 1 'Jv Cole-Haan v2^o im&. Crabtree & Evelyn OB^ Dansk Dockers Outlet by Designs Escada Garnet Hill Giorgio Armani .*, . >; General Store Godiva Chocolatier Hickey-Freeman/ "' ft & */ Bobby Jones '.-[ J. Crew At Historic Manch Johnston & Murphy Jones New York Levi's Outlet by Designs Manchester Lion's Share Bakery Maidenform Designer Outlets Mikasa Movado Visit us online at stervermo OshKosh B'Gosh Overland iMrt Peruvian Connection Polo/Ralph Lauren Seiko The Company Store Timberland Tumi/Kipling Versace Company Store Yves Delorme JUh** ! for Palais Royal Phone (800) 955 SHOP WS »'" A *Wtev : s-:s. 54 <M 5 "J* "^^SShfcjiy ORIGINS GAUCftV formerly TRIBAL ARTS GALLERY, NYC Ceremonial and modern sculpture for new and advanced collectors Open 7 Days 36 Main St. POB 905 413-298-0002 Stockbridge, MA 01262 Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Ray and Maria Stata Music Directorship Bernard Haitink, Principal Guest Conductor One Hundred and Twentieth Season, 2000-2001 SYMPHONY HALL CENTENNIAL SEASON Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Peter A. Brooke, Chairman Dr. Nicholas T. Zervas, President Julian Cohen, Vice-Chairman Harvey Chet Krentzman, Vice-Chairman Deborah B. Davis, Vice-Chairman Vincent M. O'Reilly, Treasurer Nina L. Doggett, Vice-Chairman Ray Stata, Vice-Chairman Harlan E. Anderson John F. Cogan, Jr. Edna S. -

Ear and There Monday, February 8, 2010

Earplay San Francisco Season Concerts 2010 Season Herbst Theatre, 7:30 PM Pre-concert talk 6:45 p.m. Earplay 25: Ear and there Monday, February 8, 2010 Bruce Christian Bennett , Sam Nichols, Kaija Saariaho Carlos Sanchez-Gutiérrez, Seymour Shifrin Earplay 25: Ear and There Earplay 25: Outside In Monday, March 22, 2010 February 8, 2010 Lori Dobbins, Michael Finnissy, Chris Trebue Moore Arnold Schoenberg, Judith Weir Earplay 25: Ports and Portals Monday, May 24, 2010 as part of the San Francisco International Arts Festival Jorge Liderman Hyo-shin NaWayne Peterson Tolga Yayalar earplay commission/world premiere Earplay commission West-Coast Premiere 2009 Winner, Earplay Donald Aird Memorial Composition Competition elcome to Earplay’s 25th San Francisco season. Our mission is to nurture new chamber music — W composition, performance, and audience —all vital components. Each concert features the renowned members of the Earplay ensemble performing as soloists and ensemble artists, along with special guests. Over twenty-five years, Earplay has made an enormous contribution to the bay area music community with new works commissioned each season. The Earplay ensemble has performed hundreds of works by more than two hundred Earplay 2010 composers including presenting more than one hundred world Donald Aird premieres. This season the ensemble continues exploring by performing works by composers new to Earplay. Memorial The 2010 season highlights the tremendous amount Composers Competition of innovation that happens here in the Bay Area. The season is a nexus of composers and performers adventuring into new Downloadable application at: musical realms. Most of the composers this season have strong www.earplay.org/competitions ties to the Bay Area — as home, a place of study or a place they create. -

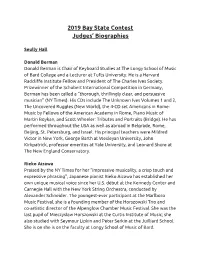

2019 Bay State Contest Judges' Biographies

2019 Bay State Contest Judges’ Biographies Seully Hall Donald Berman Donald Berman is Chair of Keyboard Studies at The Longy School of Music of Bard College and a Lecturer at Tufts University. He is a Harvard Radcliffe Institute Fellow and President of The Charles Ives Society. Prizewinner of the Schubert International Competition in Germany, Berman has been called a “thorough, thrillingly clear, and persuasive musician” (NY Times). His CDs include The Unknown Ives Volumes 1 and 2, The Uncovered Ruggles (New World), the 4-CD set Americans in Rome: Music by Fellows of the American Academy in Rome, Piano Music of Martin Boykan, and Scott Wheeler: Tributes and Portraits (Bridge). He has performed throughout the USA as well as abroad in Belgrade, Rome, Beijing, St. Petersburg, and Israel. His principal teachers were Mildred Victor in New York, George Barth at Wesleyan University, John Kirkpatrick, professor emeritus at Yale University, and Leonard Shure at The New England Conservatory. Rieko Aizawa Praised by the NY Times for her “impressive musicality, a crisp touch and expressive phrasing”, Japanese pianist Rieko Aizawa has established her own unique musical voice since her U.S. début at the Kennedy Center and Carnegie Hall with the New York String Orchestra, conducted by Alexander Schneider. The youngest-ever participant at the Marlboro Music Festival, she is a founding member of the Horszowski Trio and co-artistic director of the Alpenglow Chamber Music Festival. She was the last pupil of Mieczyslaw Horszowski at the Curtis Institute of Music; she also studied with Seymour Lipkin and Peter Serkin at the Juilliard School. -

Detailed Biography

c/o Justin Stanley JMS Artist Management 89 Wenham Street #2 Jamaica Plain, MA 02139 857-210-4706 [email protected] lydianquartet.com LYDIAN STRING QUARTET - DETAILED BIOGRAPHY From its beginning in 1980, the Lydian Quartet has embraced the full range of the string quartet repertory with curiosity, virtuosity, and dedication to the highest artistic ideals of music making. In its formative years, the quartet studied repertoire with Robert Koff, a founding member of the Julliard String Quartet who had joined the Brandeis faculty in 1958. Forging a personality of their own, the Lydians were awarded top prizes in international string quartet competitions, including Evian, Portsmouth and Banff, culminating in 1984 with the Naumburg Award for Chamber Music. In the years to follow, the quartet continued to build a reputation for their depth of interpretation, performing with "a precision and involvement marking them as among the world's best quartets" (Chicago Sun-Times). Residing at Brandeis University, in Waltham, Massachusetts, the Lydians continue to offer compelling, thoughtful, and dramatic performances of the quartet literature. From the acknowledged masterpieces of the classical, romantic, and modern eras to the remarkable compositions written by today's cutting edge composers, the quartet approaches music-making with a sense of exploration and personal expression that is timeless. The LSQ has performed extensively throughout the United States at venues such as Jordan Hall in Boston; the Kennedy Center and the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.; Lincoln Center, Miller Theater, and Weill Recital Hall in New York City; the Pacific Rim Festival at the University of California at Santa Cruz; and the Slee Beethoven Series at the University at Buffalo. -

A List of Symphonies the First Seven: 1

A List of Symphonies The First Seven: 1. Anton Webern, Symphonie, Op. 21 2. Artur Schnabel, Symphony No. 2 3. Fartein Valen, Symphony No. 4 4. Humphrey Searle, Symphony No. 5 5. Roger Sessions, Symphony No. 8 6. Arnold Schoenberg, Kammersymphonie Nr. 2 op. 38b 7. Arnold Schoenberg, Kammersymphonie Nr. 1 op. 9b The Others: Stefan Wolpe, Symphony No. 1 Matthijs Vermeulen, Symphony No. 6 (“Les Minutes heureuses”) Allan Pettersson, Symphony No. 4, Symphony No. 5, Symphony No. 6, Symphony No. 8, Symphony No. 13 Wallingford Riegger, Symphony No. 4, Symphony No. 3 Fartein Valen, Symphony No. 1, Symphony No. 2 Alain Bancquart, Symphonie n° 1, Symphonie n° 5 (“Partage de midi” de Paul Claudel) Hanns Eisler, Kammer-Sinfonie Günter Kochan, Sinfonie Nr.3 (In Memoriam Hanns Eisler), Sinfonie Nr.4 Ross Lee Finney, Symphony No. 3, Symphony No. 2 Darius Milhaud, Symphony No. 8 (“Rhodanienne”, Op. 362: Avec mystère et violence) Gian Francesco Malipiero, Symphony No. 9 ("dell'ahimé"), Symphony No. 10 ("Atropo"), & Symphony No. 11 ("Della Cornamuse") Roberto Gerhard, Symphony No. 1, No. 2 ("Metamorphoses") & No. 4 (“New York”) E.J. Moeran, Symphony in g minor Roger Sessions, Symphony No. 4, Symphony No. 5, Symphony No. 9 Edison Denisov, Symphony No. 1, Symphony No. 2; Chamber Symphony No. 1 (1982) Artur Schnabel, Symphony No. 1 Sir Edward Elgar, Symphony No. 2, Symphony No. 1 Frank Corcoran, Symphony No. 3, Symphony No. 2 Ernst Krenek, Symphony No. 5 Erwin Schulhoff, Symphony No. 1 Gerd Domhardt, Sinfonie Nr.2 Alvin Etler, Symphony No. 1 Meyer Kupferman, Symphony No. 4 Humphrey Searle, Symphony No. -

Moses Und Aron and Viennese Jewish Modernism

Finding Music’s Words: Moses und Aron and Viennese Jewish Modernism Maurice Cohn Candidate for Senior Honors in History, Oberlin College Thesis Advisor: Annemarie Sammartino Submitted Spring 2017 !2 Table of Contents Acknowledgments 3 Introduction 4 Chapter One 14 Chapter Two 34 Chapter Three 44 Conclusion 58 Bibliography 62 !3 Acknowledgments I have tremendous gratitude and gratefulness for all of the people who helped make this thesis a reality. There are far too many individuals for a complete list here, but I would like to mention a few. Firstly, to my advisor Ari Sammartino, who also chaired the honors seminar this year. Her intellectual guidance has been transformational for me, and I am incredibly thankful to have had her mentorship. Secondly, to the honors seminar students for 2016—2017. Their feedback and camaraderie was a wonderful counterweight to a thesis process that is often solitary. Thirdly, to Oberlin College and Conservatory. I have benefited enormously from my ability to be a double-degree student here, and am continually amazed by the support and dedication of both faculties to make this program work. And finally to my parents, Steve Cohn and Nancy Eberhardt. They were my first teachers, and remain my intellectual role models. !4 Introduction In 1946, Arnold Schoenberg composed a trio for violin, viola, and cello. Schoenberg earned his reputation as the quintessential musical modernist through complex, often gargantuan pieces with expansive and closely followed musical structures. By contrast, the musical building blocks of the trio are small and the writing is fragmented. The composer Martin Boykan wrote that the trio “is marked by interpolations, interruptions, even non-sequiturs, so that at times Schoenberg seems to be poised at the edge of incoherence.”1 Scattered throughout the piece are musical allusions to the Viennese waltz. -

DAVID RAKOWSKI: WINGED CONTRAPTION PERSISTENT MEMORY | PIANO CONCERTO DAVID RAKOWSKI B

DAVID RAKOWSKI: WINGED CONTRAPTION PERSISTENT MEMORY | PIANO CONCERTO DAVID RAKOWSKI b. 1958 PERSISTENT MEMORY PERSISTENT MEMORY (1996–97) PIANO CONCERTO [1] I. Elegy 9:05 [2] II. Variations, Scherzo, and Variations 12:01 WINGED CONTRAPTION PIANO CONCERTO (2005–06) [3] I. Freely; Vivace 9:30 MARILYN NONKEN piano and toy piano [4] II. Adagio 6:53 BOSTON MODERN ORCHESTRA PROJECT [5] III. Scherzando 5:28 GIL ROSE, CONDUCTOR [6] IV. Poco andante, quasi adagietto, con gusty; Allegro; Cadenza; Allegro 12:04 [7] WINGED CONTRAPTION (1991) 9:24 TOTAL 64:27 COMMENT get further and further away and something would happen to bring the elegy back. That “something” became a repeated note climax in the scherzo from which the string sections would explode, first in unison, and then into another 16-note chord; that chord brings back By David Rakowski the meandering elegy music as a variation. A codetta exposes the three cellos and puts I was at the American Academy in Rome when the commission offer from Orpheus them back together as a section, themselves ending with a meandering half-step. Chamber Orchestra came. At the time, my wife’s mother had cancer with a short time The Piano Concerto came about through the tireless efforts of Marilyn Nonken, with to live, and I couldn’t afford plane fare to come to the funeral. So I was feeling a kind of whom I’d collaborated many times, and so my idea was to acknowledge her in the piece melancholy as I started work on the piece. by building it from existing piano études either written for her or that she had recorded. -

The Late Choral Works of Igor Stravinsky

THE LATE CHORAL WORKS OF IGOR STRAVINSKY: A RECEPTION HISTORY _________________________________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia ________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts ____________________________ by RUSTY DALE ELDER Dr. Michael Budds, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2008 The undersigned, as appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled THE LATE CHORAL WORKS OF IGOR STRAVINSKY: A RECEPTION HISTORY presented by Rusty Dale Elder, a candidate for the degree of Master of Arts, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. _________________________________________ Professor Michael Budds ________________________________________ Professor Judith Mabary _______________________________________ Professor Timothy Langen ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to each member of the faculty who participated in the creation of this thesis. First and foremost, I wish to recognize the ex- traordinary contribution of Dr. Michael Budds: without his expertise, patience, and en- couragement this study would not have been possible. Also critical to this thesis was Dr. Judith Mabary, whose insightful questions and keen editorial skills greatly improved my text. I also wish to thank Professor Timothy Langen for his thoughtful observations and support. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………...ii ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………………...v CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION: THE PROBLEM OF STRAVINSKY’S LATE WORKS…....1 Methodology The Nature of Relevant Literature 2. “A BAD BOY ALL THE WAY”: STRAVINSKY’S SECOND COMPOSITIONAL CRISIS……………………………………………………....31 3. AFTER THE BOMB: IN MEMORIAM DYLAN THOMAS………………………45 4. “MURDER IN THE CATHEDRAL”: CANTICUM SACRUM AD HONOREM SANCTI MARCI NOMINIS………………………………………………………...60 5. -

Martin Brody Education BA, Summa Cum Laude, Phi Beta

Martin Brody Department of Music Wellesley College Wellesley, MA 02281 617-283-2085 [email protected] Education B.A., summa cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa, Amherst College, 1972 M.M. (1975), M.M.A. (1976), D.M.A. (1981), Yale School of Music Additional studies in music theory and analysis with Martin Boykan and Allan Keiler, Brandeis University (1977); Additional studies in electronic music and digital signal processing with Barry Vercoe, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1979) Principal composition teachers: Donald Wheelock, Lewis Spratlan, Yehudi Wyner, Robert Morris, Seymour Shifrin Academic Positions Catherine Mills Davis Professor of Music, Wellesley College (member of faculty since 1979) Visiting Professor of Music at Brandeis University, 1994 Visiting Associate Professor of Music at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1989 Assistant Professor of Music at Bowdoin College, 1978-79 Assistant Professor of Music at Mount Holyoke College, 1977- Other Professional Employment Andrew Heiskell Arts Director, American Academy in Rome, 2007-10 term Executive Director, Thomas J. Watson Foundation, 1987-9 term Honors and Awards Roger Sessions Memorial Fellow in Music, Bogliasco Foundation, 2004 Composer-in-Residence, William Walton Estate, La Mortella, 2004 Fromm Foundation at Harvard, Composer Commission, 2004 Fromm Composer-in-Residence, American Academy in Rome, fall 2001 John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship, 2000 Pinanski Prize for Excellence in Teaching, Wellesley College, 2000 Commission for Earth Studies from Duncan Theater/MacArthur -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1990

FESTIVAL OF CONTE AUGUST 4th - 9th 1990 j:*sT?\€^ S& EDITION PETERS -&B) t*v^v- iT^^ RECENT ADDITIONS TO OUR CONTEMPORARY MUSIC CATALOGUE P66438a John Becker Concerto for Violin and Orchestra. $20.00 Violin and Piano (Edited by Gregory Fulkerson) P67233 Martin Boykan String Quartet no. 3 $40.00 (Score and Parts) (1988 Walter Hinrichsen Award) P66832 George Crumb Apparition $20.00 Elegiac Songs and Vocalises for Soprano and Amplified Piano P67261 Roger Reynolds Whispers Out of Time $35.00 String Orchestra (Score)* (1989 Pulitzer Prize) P67283 Bruce J. Taub Of the Wing of Madness $30.00 Chamber Orchestra (Score)* P67273 Chinary Ung Spiral $15.00 Vc, Pf and Perc (Score) (1989 Grawemeyer and Friedheim Award) P66532 Charles Wuorinen The Blue Bamboula $15.00 Piano Solo * Performance materials availablefrom our rental department C.F. PETERS CORPORATION ^373 Park Avenue So./New York, NY 10016/Phone (212) 686-4l47/Fax (212) 689-9412 1990 FESTIVAL OF CONTEMPORARY MUSIC Oliver Knussen, Festival Coordinator by the sponsored TanglewGDd TANGLEWOOD MUSIC CENTER Music Leon Fleisher, Artistic Director Center Gilbert Kalish, Chairman of the Faculty Lukas Foss, Composer-in-Residence Oliver Knussen, Coordinator of Contemporary Music Activities Bradley Lubman, Assistant to Oliver Knussen Richard Ortner, Administrator Barbara Logue, Assistant to Richard Ortner James E. Whitaker, Chief Coordinator Carol Wood worth, Secretary to the Faculty Harry Shapiro, Orchestra Manager Works presented at this year's Festival were prepared under the guidance of the following Tanglewood Music Center Faculty: Frank Epstein Donald MacCourt Norman Fischer John Oliver Gilbert Kalish Peter Serkin Oliver Knussen Joel Smirnoff loel Krosnick Yehudi Wyner 1990 Visiting Composer/Teachers Elliott Carter John Harbison Tod Machover Donald Martino George Perle Steven Stucky The 1990 Festival of Contemporary Music is supported by a gift from Dr. -

American Society of University Composers

American Society of University Composers Proceedings of the First Annual Conference /April 1966 AMERICAN SOCIETY OF UNIVERSITY COMPOSERS Copyright © 1968 The American Society of University Composers, Inc. AMERICAN SOCIETY OF UNIVERSITY COMPOSERS Proceedings of the First Annual Conference, April, 1966 Held at New York University and Columbia University With the assistance of The Fromm Music Foundation Founding Committee BENJAMIN BORETZ, DONALD MARTINO, J. K. RANDALL, CLAUDIO SPIES, HENRY WEINBERG, PETER WESTERGAARD, CHARLES WUORINEN National Council MARTIN BOYKAN, BARNEY CHILDS, ROBERT COGAN, RANDOLPH E. COLEMAN (Chafrman), CARLTON GAMER, LEO KRAFT, DONALD MAclNNIS Executive Committee RICHMOND BROWNE, DAVID EPSTEIN, WILLIAM HIBBARD, HUBERT S . HOWE, JR., BEN JOHNSTON, JOEL MANDELBAUM, HARVEY SOLLBERGER, RoY TRAVIS Editor of Proceedings HUBERT s. HOWE, JR. CONTENTS I Proceedings of the 1966 Conference Part I: The University and the Composing Profession: Prospects and Problems 7 ANDREW W. IMBRIE The University of California Series in Contemporary Music 14 IAIN HAMILTON The University and the Composing Profession: Prospects and Problems 20 CHARLES WUORINEN Performance of New Music in American Universities 23 STEFAN BAUER-MENGELBERG Impromptu Remarks on New Methods of Music Printing Part II: Computer Performance of Music 29 J. K. RANDALL Introduction 30 HERBERT BRUN On the Conditions under which Computers would Assist a Composer in Creating Music of Contemporary Relevance and Significance 38 ERCOLINO FERRETTI Some Research Notes on Music with -

PROGRAM NOTES 5 by Nicholas Alexander Brown

A Fine Centennial FRIDAY MAY 16, 2014 8:00 A Fine Centennial FRIDAY MAY 16, 2014 8:00 JORDAN HALL AT NEW ENGLAND CONSERVATORY Pre-concert talk with Nicholas Alexander Brown, Music Director & Founder, The Irving Fine Society – 7:00 IRVING FINE Blue Towers (1959) Remarks by Eric Chasalow, Irving G. Fine Professor of Music, Brandeis University and Emily and Claudia Fine IRVING FINE Diversions for Orchestra (1959) I. Little Toccata II. Flamingo Polka III. Koko’s Lullaby IV. The Red Queen’s Gavotte HAROLD SHAPERO Serenade in D for string orchestra (1945) I. Adagio—Allegro II. Menuetto (scherzando): Allegretto III. Larghetto, poco adagio IV. Intermezzo: Andantino con moto V. Finale: Allegro assai, poco presto INTERMISSION ARTHUR BERGER Prelude, Aria, and Waltz for string orchestra (1945, rev. 1982) I. Prelude II. Aria III. Waltz IRVING FINE Symphony (1962) I. Intrada: Andante quasi allegretto II. Capriccio: Allegro con spirito III. Ode: Grave GIL ROSE, Conductor Presented in collaboration with the Fine Family, The Irving Fine Society, and Brandeis University. PROGRAM NOTES 5 by Nicholas Alexander Brown This evening’s concert commemorates the Irving Fine centennial TINA TALLON with works by Fine and two of his most revered friends and colleagues, Harold Shapero and Arthur Berger. These three composers, along with Leonard Bernstein and Lukas Foss, are known collectively as the Boston School or Boston Group. Influenced greatly by Aaron TONIGHT’S PERFORMERS Copland, Serge Koussevitzky, Igor Stravinsky, and Nadia Boulanger (with whom several of them studied), these composers carved a place at the forefront of American music. Fine, Shapero, and Berger all spent time as students at at Harvard before making FLUTE TROMBONE VIOLIN II Brandeis University their musical home.