American Society of University Composers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 2001, Tanglewood

SEMI OIAWA MUSIC DIRECTOR BERNARD HAITINK PRINCIPAL GUEST CONDUCTOR • i DALE CHIHULY INSTALLATIONS AND SCULPTURE / "^ik \ *t HOLSTEN GALLERIES CONTEMPORARY GLASS SCULPTURE ELM STREET, STOCKBRIDGE, MA 01262 . ( 41 3.298.3044 www. holstenga I leries * Save up to 70% off retail everyday! Allen-Edmoi. Nick Hilton C Baccarat Brooks Brothers msSPiSNEff3svS^:-A Coach ' 1 'Jv Cole-Haan v2^o im&. Crabtree & Evelyn OB^ Dansk Dockers Outlet by Designs Escada Garnet Hill Giorgio Armani .*, . >; General Store Godiva Chocolatier Hickey-Freeman/ "' ft & */ Bobby Jones '.-[ J. Crew At Historic Manch Johnston & Murphy Jones New York Levi's Outlet by Designs Manchester Lion's Share Bakery Maidenform Designer Outlets Mikasa Movado Visit us online at stervermo OshKosh B'Gosh Overland iMrt Peruvian Connection Polo/Ralph Lauren Seiko The Company Store Timberland Tumi/Kipling Versace Company Store Yves Delorme JUh** ! for Palais Royal Phone (800) 955 SHOP WS »'" A *Wtev : s-:s. 54 <M 5 "J* "^^SShfcjiy ORIGINS GAUCftV formerly TRIBAL ARTS GALLERY, NYC Ceremonial and modern sculpture for new and advanced collectors Open 7 Days 36 Main St. POB 905 413-298-0002 Stockbridge, MA 01262 Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Ray and Maria Stata Music Directorship Bernard Haitink, Principal Guest Conductor One Hundred and Twentieth Season, 2000-2001 SYMPHONY HALL CENTENNIAL SEASON Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Peter A. Brooke, Chairman Dr. Nicholas T. Zervas, President Julian Cohen, Vice-Chairman Harvey Chet Krentzman, Vice-Chairman Deborah B. Davis, Vice-Chairman Vincent M. O'Reilly, Treasurer Nina L. Doggett, Vice-Chairman Ray Stata, Vice-Chairman Harlan E. Anderson John F. Cogan, Jr. Edna S. -

A Historiography of Musical Historicism: the Case Of

A HISTORIOGRAPHY OF MUSICAL HISTORICISM: THE CASE OF JOHANNES BRAHMS THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of Texas State University-San Marcos in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of MUSIC by Shao Ying Ho, B.M. San Marcos, Texas May 2013 A HISTORIOGRAPHY OF MUSICAL HISTORICISM: THE CASE OF JOHANNES BRAHMS Committee Members Approved: _____________________________ Kevin E. Mooney, Chair _____________________________ Nico Schüler _____________________________ John C. Schmidt Approved: ___________________________ J. Michael Willoughby Dean of the Graduate College COPYRIGHT by Shao Ying Ho 2013 FAIR USE AND AUTHOR’S PERMISSION STATEMENT Fair Use This work is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public Law 94-553, section 107). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations from this material are allowed with proper acknowledgement. Use of this material for financial gain without the author’s express written permission is not allowed. Duplication Permission As the copyright holder of this work, I, Shao Ying Ho, authorize duplication of this work, in whole or in part, for educational or scholarly purposes only. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My first and foremost gratitude is to Dr. Kevin Mooney, my committee chair and advisor. His invaluable guidance, stimulating comments, constructive criticism, and even the occasional chats, have played a huge part in the construction of this thesis. His selfless dedication, patience, and erudite knowledge continue to inspire and motivate me. I am immensely thankful to him for what I have become in these two years, both intellectually and as an individual. I am also very grateful to my committee members, Dr. -

Focus 2020 Pioneering Women Composers of the 20Th Century

Focus 2020 Trailblazers Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century The Juilliard School presents 36th Annual Focus Festival Focus 2020 Trailblazers: Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Joel Sachs, Director Odaline de la Martinez and Joel Sachs, Co-curators TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Focus 2020 3 For the Benefit of Women Composers 4 The 19th-Century Precursors 6 Acknowledgments 7 Program I Friday, January 24, 7:30pm 18 Program II Monday, January 27, 7:30pm 25 Program III Tuesday, January 28 Preconcert Roundtable, 6:30pm; Concert, 7:30pm 34 Program IV Wednesday, January 29, 7:30pm 44 Program V Thursday, January 30, 7:30pm 56 Program VI Friday, January 31, 7:30pm 67 Focus 2020 Staff These performances are supported in part by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are not permitted in the auditorium. Introduction to Focus 2020 by Joel Sachs The seed for this year’s Focus Festival was planted in December 2018 at a Juilliard doctoral recital by the Chilean violist Sergio Muñoz Leiva. I was especially struck by the sonata of Rebecca Clarke, an Anglo-American composer of the early 20th century who has been known largely by that one piece, now a staple of the viola repertory. Thinking about the challenges she faced in establishing her credibility as a professional composer, my mind went to a group of women in that period, roughly 1885 to 1930, who struggled to be accepted as professional composers rather than as professional performers writing as a secondary activity or as amateur composers. -

Ear and There Monday, February 8, 2010

Earplay San Francisco Season Concerts 2010 Season Herbst Theatre, 7:30 PM Pre-concert talk 6:45 p.m. Earplay 25: Ear and there Monday, February 8, 2010 Bruce Christian Bennett , Sam Nichols, Kaija Saariaho Carlos Sanchez-Gutiérrez, Seymour Shifrin Earplay 25: Ear and There Earplay 25: Outside In Monday, March 22, 2010 February 8, 2010 Lori Dobbins, Michael Finnissy, Chris Trebue Moore Arnold Schoenberg, Judith Weir Earplay 25: Ports and Portals Monday, May 24, 2010 as part of the San Francisco International Arts Festival Jorge Liderman Hyo-shin NaWayne Peterson Tolga Yayalar earplay commission/world premiere Earplay commission West-Coast Premiere 2009 Winner, Earplay Donald Aird Memorial Composition Competition elcome to Earplay’s 25th San Francisco season. Our mission is to nurture new chamber music — W composition, performance, and audience —all vital components. Each concert features the renowned members of the Earplay ensemble performing as soloists and ensemble artists, along with special guests. Over twenty-five years, Earplay has made an enormous contribution to the bay area music community with new works commissioned each season. The Earplay ensemble has performed hundreds of works by more than two hundred Earplay 2010 composers including presenting more than one hundred world Donald Aird premieres. This season the ensemble continues exploring by performing works by composers new to Earplay. Memorial The 2010 season highlights the tremendous amount Composers Competition of innovation that happens here in the Bay Area. The season is a nexus of composers and performers adventuring into new Downloadable application at: musical realms. Most of the composers this season have strong www.earplay.org/competitions ties to the Bay Area — as home, a place of study or a place they create. -

Louise Talma Honored

Louise Talma Honored It was a way of saying thank you and a warm tribute to Louise Talma on Saturday night, February 5, when a host of her friends, colleagues on the Hunter faculty, students, and other music lovers gathered in the Hunter College Playhouse for a concert billed as "A Celebration for Louise." Performing withherqn the presentation of her own com- positions were friends and colleagues, among them Phyl- lis Curtin, Charles Bressler, Lukas . Foss, Herbert Rogers, Peter Basquin an3 the Gregg Smith ,Singers. One of the numbers, "Voices of Peace,!' which she composed in 1973, was performed for the first time in New York. The Monday after the concert, Louise Talma began her -50th year of teaching at Hunter College. Now Professor Emeritus, she had-taught thre'e courses in the fall semester and is now teaching one in th'e spring, all without pay. "I know I can ell on her," says James Harrison, chairman of the music department, "anytime I need help. She's a fine teacher in the old tradition, with high standards, and she's demanding of herself and of her students." Miss Talina, who was born in. France while her mother, an American, was singing opera'there, is a composer of Louise Talma 'mbto 6y iy~asliL'ahghn note. She was the first woman to be elected to the Na- tional lnstitute of Arts and Letters, and the first American woman composer to have a full-length, 'three-act opera produced by $imajor European opera house. This was "The Alcestiad," which was based on a libretto by Thorn- ton Wilder, and was performed by the Frankfurt Opera Company. -

Martin Boykan Elegy, String Quartet No

NWCR786 Martin Boykan Elegy, String Quartet No. 4, Epithalamion Part II 4. IV Der Spinnerin Lied (Brentano) ......... (1:56) 5. V The Winters are so short (Dickinson) (3:29) 6. VI Um Mitternacht (Goethe) ................. (4:36) 7. VII A Bronze Immortal Takes Leave of Han (Li Ho) .................................. (7:09) Jane Bryden, soprano; The Brandeis Contemporary Chamber Players: Christopher Krueger, flute; William Wrzesien, clarinet; Nancy Cirillo, violin; Rhonda Rider, cello; James Orleans, bass; Sally Pinkas, piano; David Hoose, conductor String Quartet No. 4 (1996) ........................................ (17:49) 8. I Vigoroso, II Adagio espressivo Lydian String Quartet: Daniel Stepner, violin; Judith Eissenberg, violin; Mary Ruth Ray, viola; Rhonda Rider, cello Epithalamion (1986) ................................................... (11:01) 10. I Love Song (Ammons) (Prelude) ....... (2:54) 11. II Anon., sixteenth-century poem (Scherzo) .................................................. (1:51) 12. III Epithalamion (Spenser) (Invocation) (6:17) James Maddalena, baritone; Nancy Cirillo, Elegy (1982) ............................................................... (33:19) violin; Virginia Crumb, harp Part I Total Playing Time: 62:22 1. I Ist alles denn verloren (Goethe) ........ (5:25) 2. II A se stesso (Leopardi) ....................... (5:34) Ê 1988, 1998 & © 1998 Composers Recordings, Inc. 3. III Agonia (Ungaretti) ............................ (5:10) © 2007 Anthology of Recorded Music, Inc. Notes and experience, but they are somehow -

A Performance Guide to Wallace Stevens' Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird As Set by Louise Talma

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 2020 A Performance Guide to Wallace Stevens' Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird as Set by Louise Talma Meredith Melvin Johnson The University of Soutthern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Meredith Melvin, "A Performance Guide to Wallace Stevens' Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird as Set by Louise Talma" (2020). Dissertations. 1787. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1787 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A PERFORMANCE GUIDE TO WALLACE STEVENS’ THIRTEEN WAYS OF LOOKING AT A BLACKBIRD AS SET BY LOUISE TALMA by Meredith Melvin Johnson A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School, the College of Arts and Sciences and the School of Music at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Approved by: Dr. Christopher Goertzen, Committee Chair Dr. Jonathan Yarrington Dr. Kimberley Davis Dr. Maryann Kyle Dr. Douglas Rust ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ Dr. Christopher Goertzen Dr. Jay Dean Dr. Karen S. Coats Committee Chair Director of School Dean of the Graduate School May 2020 COPYRIGHT BY Meredith Melvin Johnson 2020 Published by the Graduate School ABSTRACT This dissertation presents a two-fold discourse, first to provide a contextual source for singers interested in 20th century composer Louise Talma, and second to provide an analytical guide to Talma’s adaption of Wallace Stevens’ poem Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird for voice, oboe, and piano. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1963-1964

TANGLEWOOD Festival of Contemporary American Music August 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 1964 Sponsored by the Berkshire Music Center In Cooperation with the Fromm Music Foundation RCA Victor R£D SEAL festival of Contemporary American Composers DELLO JOIO: Fantasy and Variations/Ravel: Concerto in G Hollander/Boston Symphony Orchestra/Leinsdorf LM/LSC-2667 COPLAND: El Salon Mexico Grofe-. Grand Canyon Suite Boston Pops/ Fiedler LM-1928 COPLAND: Appalachian Spring The Tender Land Boston Symphony Orchestra/ Copland LM/LSC-240i HOVHANESS: BARBER: Mysterious Mountain Vanessa (Complete Opera) Stravinsky: Le Baiser de la Fee (Divertimento) Steber, Gedda, Elias, Mitropoulos, Chicago Symphony/Reiner Met. Opera Orch. and Chorus LM/LSC-2251 LM/LSC-6i38 FOSS: IMPROVISATION CHAMBER ENSEMBLE Studies in Improvisation Includes: Fantasy & Fugue Music for Clarinet, Percussion and Piano Variations on a Theme in Unison Quintet Encore I, II, III LM/LSC-2558 RCA Victor § © The most trusted name in sound BERKSHIRE MUSIC CENTER ERICH Leinsdorf, Director Aaron Copland, Chairman of the Faculty Richard Burgin, Associate Chairman of the Faculty Harry J. Kraut, Administrator FESTIVAL of CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN MUSIC presented in cooperation with THE FROMM MUSIC FOUNDATION Paul Fromm, President Alexander Schneider, Associate Director DEPARTMENT OF COMPOSITION Aaron Copland, Head Gunther Schuller, Acting Head Arthur Berger and Lukas Foss, Guest Teachers Paul Jacobs, Fromm Instructor in Contemporary Music Stanley Silverman and David Walker, Administrative Assistants The Berkshire Music Center is the center for advanced study in music sponsored by the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Erich Leinsdorf, Music Director Thomas D. Perry, Jr., Manager BALDWIN PIANO RCA VICTOR RECORDS — 1 PERSPECTIVES OF NEW MUSIC Participants in this year's Festival are invited to subscribe to the American journal devoted to im- portant issues of contemporary music. -

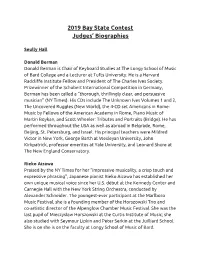

2019 Bay State Contest Judges' Biographies

2019 Bay State Contest Judges’ Biographies Seully Hall Donald Berman Donald Berman is Chair of Keyboard Studies at The Longy School of Music of Bard College and a Lecturer at Tufts University. He is a Harvard Radcliffe Institute Fellow and President of The Charles Ives Society. Prizewinner of the Schubert International Competition in Germany, Berman has been called a “thorough, thrillingly clear, and persuasive musician” (NY Times). His CDs include The Unknown Ives Volumes 1 and 2, The Uncovered Ruggles (New World), the 4-CD set Americans in Rome: Music by Fellows of the American Academy in Rome, Piano Music of Martin Boykan, and Scott Wheeler: Tributes and Portraits (Bridge). He has performed throughout the USA as well as abroad in Belgrade, Rome, Beijing, St. Petersburg, and Israel. His principal teachers were Mildred Victor in New York, George Barth at Wesleyan University, John Kirkpatrick, professor emeritus at Yale University, and Leonard Shure at The New England Conservatory. Rieko Aizawa Praised by the NY Times for her “impressive musicality, a crisp touch and expressive phrasing”, Japanese pianist Rieko Aizawa has established her own unique musical voice since her U.S. début at the Kennedy Center and Carnegie Hall with the New York String Orchestra, conducted by Alexander Schneider. The youngest-ever participant at the Marlboro Music Festival, she is a founding member of the Horszowski Trio and co-artistic director of the Alpenglow Chamber Music Festival. She was the last pupil of Mieczyslaw Horszowski at the Curtis Institute of Music; she also studied with Seymour Lipkin and Peter Serkin at the Juilliard School. -

Detailed Biography

c/o Justin Stanley JMS Artist Management 89 Wenham Street #2 Jamaica Plain, MA 02139 857-210-4706 [email protected] lydianquartet.com LYDIAN STRING QUARTET - DETAILED BIOGRAPHY From its beginning in 1980, the Lydian Quartet has embraced the full range of the string quartet repertory with curiosity, virtuosity, and dedication to the highest artistic ideals of music making. In its formative years, the quartet studied repertoire with Robert Koff, a founding member of the Julliard String Quartet who had joined the Brandeis faculty in 1958. Forging a personality of their own, the Lydians were awarded top prizes in international string quartet competitions, including Evian, Portsmouth and Banff, culminating in 1984 with the Naumburg Award for Chamber Music. In the years to follow, the quartet continued to build a reputation for their depth of interpretation, performing with "a precision and involvement marking them as among the world's best quartets" (Chicago Sun-Times). Residing at Brandeis University, in Waltham, Massachusetts, the Lydians continue to offer compelling, thoughtful, and dramatic performances of the quartet literature. From the acknowledged masterpieces of the classical, romantic, and modern eras to the remarkable compositions written by today's cutting edge composers, the quartet approaches music-making with a sense of exploration and personal expression that is timeless. The LSQ has performed extensively throughout the United States at venues such as Jordan Hall in Boston; the Kennedy Center and the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.; Lincoln Center, Miller Theater, and Weill Recital Hall in New York City; the Pacific Rim Festival at the University of California at Santa Cruz; and the Slee Beethoven Series at the University at Buffalo. -

A List of Symphonies the First Seven: 1

A List of Symphonies The First Seven: 1. Anton Webern, Symphonie, Op. 21 2. Artur Schnabel, Symphony No. 2 3. Fartein Valen, Symphony No. 4 4. Humphrey Searle, Symphony No. 5 5. Roger Sessions, Symphony No. 8 6. Arnold Schoenberg, Kammersymphonie Nr. 2 op. 38b 7. Arnold Schoenberg, Kammersymphonie Nr. 1 op. 9b The Others: Stefan Wolpe, Symphony No. 1 Matthijs Vermeulen, Symphony No. 6 (“Les Minutes heureuses”) Allan Pettersson, Symphony No. 4, Symphony No. 5, Symphony No. 6, Symphony No. 8, Symphony No. 13 Wallingford Riegger, Symphony No. 4, Symphony No. 3 Fartein Valen, Symphony No. 1, Symphony No. 2 Alain Bancquart, Symphonie n° 1, Symphonie n° 5 (“Partage de midi” de Paul Claudel) Hanns Eisler, Kammer-Sinfonie Günter Kochan, Sinfonie Nr.3 (In Memoriam Hanns Eisler), Sinfonie Nr.4 Ross Lee Finney, Symphony No. 3, Symphony No. 2 Darius Milhaud, Symphony No. 8 (“Rhodanienne”, Op. 362: Avec mystère et violence) Gian Francesco Malipiero, Symphony No. 9 ("dell'ahimé"), Symphony No. 10 ("Atropo"), & Symphony No. 11 ("Della Cornamuse") Roberto Gerhard, Symphony No. 1, No. 2 ("Metamorphoses") & No. 4 (“New York”) E.J. Moeran, Symphony in g minor Roger Sessions, Symphony No. 4, Symphony No. 5, Symphony No. 9 Edison Denisov, Symphony No. 1, Symphony No. 2; Chamber Symphony No. 1 (1982) Artur Schnabel, Symphony No. 1 Sir Edward Elgar, Symphony No. 2, Symphony No. 1 Frank Corcoran, Symphony No. 3, Symphony No. 2 Ernst Krenek, Symphony No. 5 Erwin Schulhoff, Symphony No. 1 Gerd Domhardt, Sinfonie Nr.2 Alvin Etler, Symphony No. 1 Meyer Kupferman, Symphony No. 4 Humphrey Searle, Symphony No. -

Moses Und Aron and Viennese Jewish Modernism

Finding Music’s Words: Moses und Aron and Viennese Jewish Modernism Maurice Cohn Candidate for Senior Honors in History, Oberlin College Thesis Advisor: Annemarie Sammartino Submitted Spring 2017 !2 Table of Contents Acknowledgments 3 Introduction 4 Chapter One 14 Chapter Two 34 Chapter Three 44 Conclusion 58 Bibliography 62 !3 Acknowledgments I have tremendous gratitude and gratefulness for all of the people who helped make this thesis a reality. There are far too many individuals for a complete list here, but I would like to mention a few. Firstly, to my advisor Ari Sammartino, who also chaired the honors seminar this year. Her intellectual guidance has been transformational for me, and I am incredibly thankful to have had her mentorship. Secondly, to the honors seminar students for 2016—2017. Their feedback and camaraderie was a wonderful counterweight to a thesis process that is often solitary. Thirdly, to Oberlin College and Conservatory. I have benefited enormously from my ability to be a double-degree student here, and am continually amazed by the support and dedication of both faculties to make this program work. And finally to my parents, Steve Cohn and Nancy Eberhardt. They were my first teachers, and remain my intellectual role models. !4 Introduction In 1946, Arnold Schoenberg composed a trio for violin, viola, and cello. Schoenberg earned his reputation as the quintessential musical modernist through complex, often gargantuan pieces with expansive and closely followed musical structures. By contrast, the musical building blocks of the trio are small and the writing is fragmented. The composer Martin Boykan wrote that the trio “is marked by interpolations, interruptions, even non-sequiturs, so that at times Schoenberg seems to be poised at the edge of incoherence.”1 Scattered throughout the piece are musical allusions to the Viennese waltz.