H-France Review Volume 17 (2017) Page 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Litterature Francaise Contemporaine

MASTER ’S PROGRAMME ETUDES FRANCOPHONES 2DYEAR OF STUDY, 1ST SEMESTER COURSE TITLE LITTERATURE FRANCAISE CONTEMPORAINE COURSE CODE COURSE TYPE full attendance COURSE LEVEL 2nd cycle (master’sdegree) YEAR OF STUDY, SEMESTER 2dyear of study,1stsemester NUMBER OF ECTS CREDITS NUMBER OF HOURS PER WEEK 2 lecture hours+ 1 seminar hour NAME OF LECTURE HOLDER Simona MODREANU NAME OF SEMINAR HOLDER ………….. PREREQUISITES Advanced level of French A GENERAL AND COURSE-SPECIFIC COMPETENCES General competences: → Identification of the marks of critical discourse on French literature, as opposed to literary discourse; → Identification of the main moments of European and especially French culture that reflect the idea of modernity; → Indentification of the marks of the modern and contemporary dramatic discourse, as opposed to the literary discourse in prose and poetry; → Identification of the stakes of critical and theoretical discourse, as well as of the modern dramatic one, according to the historical and cultural context in which the main studied currents appear; → Interpretative competences in reading the studied texts and competence of cultural analysis in context. Course-specific competences: → Skills of interpretation of texts; → Skills to identify the cultural models present in the studied texts; → Cultural expression skills and competences; B LEARNING OUTCOMES → Reading and interpretation skills of theoretical texts that is the main argument for the existence of a literary French metadiscourse → Understanding the interaction between literature and culture in modern and contemporary society and the possibility of applying this in connection with other types of cultural content; C LECTURE CONTENT Introduction; preliminary considerations Characteristics; evolutions of contemporary French literature. The novel - the dominant genre. -

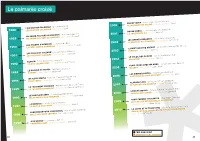

Le Palmarès Croisé

Le palmarès croisé 1988 L’EXPOSITION COLONIALE - Erik Orsenna (Seuil) INGRID CAVEN - Jean-Jacques Schuhl (Gallimard) L’EXPOSITION COLONIALE - Erik Orsenna (Seuil) 2000 ALLAH N’EST PAS OBLIGÉ - Ahmadou Kourouma (Seuil) UN GRAND PAS VERS LE BON DIEU - Jean Vautrin (Grasset) ROUGE BRÉSIL - Jean-Christophe Rufin (Gallimard) 1989 UN GRAND PAS VERS LE BON DIEU - Jean Vautrin (Grasset) 2001 LA JOUEUSE DE GO - Shan Sa (Grasset) LES CHAMPS D’HONNEUR - Jean Rouaud (Minuit) LES OMBRES ERRANTES - Pascal Quignard (Grasset) 1990 LE PETIT PRINCE CANNIBALE - Françoise Lefèvre (Actes Sud) 2002 LA MORT DU ROI TSONGOR - Laurent Gaudé (Actes Sud) 1991 LES FILLES DU CALVAIRE - Pierre Combescot (Grasset) LA MAÎTRESSE DE BRECHT - Jacques-Pierre Amette (Albin Michel) LES FILLES DU CALVAIRE - Pierre Combescot (Grasset) 2003 FARRAGO - Yann Apperry (Grasset) TEXACO - Patrick Chamoiseau (Gallimard) 1992 LE SOLEIL DES SCORTA - Laurent Gaudé (Actes Sud) L’ÎLE DU LÉZARD VERT - Edouardo Manet (Flammarion) 2004 UN SECRET - Philippe Grimbert (Grasset) 1993 LE ROCHER DE TANIOS - Amin Maalouf (Grasset) TROIS JOURS CHEZ MA MÈRE - François Weyergans (Grasset) CANINES - Anne Wiazemsky (Gallimard) 2005 MAGNUS - Sylvie Germain (Albin Michel) 1994 UN ALLER SIMPLE - Didier Van Cauwelaert (Albin Michel) LES BIENVEILLANTES - Jonathan Littell (Gallimard) BELLE-MÈRE - Claude Pujade-Renaud (Actes Sud) 2006 CONTOURS DU JOUR QUI VIENT - Léonora Miano (Plon) LE TESTAMENT FRANÇAIS - Andreï Makine (Mercure de France) 1995 ALABAMA SONG - Gilles Leroy (Mercure de France) LE TESTAMENT FRANÇAIS -

VELIKA NAGRADA FRANCOSKE AKADEMIJE ZA ROMAN (Grand Prix Du Roman De L'académie Française) Je Bila Ustanovljena Leta 1914

VELIKA NAGRADA FRANCOSKE AKADEMIJE ZA ROMAN (Grand Prix du roman de l'Académie Française) je bila ustanovljena leta 1914. Literarno nagrado podeljuje Francoska akademija. Hkrati s to nagrado, ki jo podelijo v oktobru, tradicionalno odprejo vrata za podeljevanje francoskih literarnih nagrad. Nagrajene knjige, ki jih imamo v naši knjižnični zbirki, so označene debelejše: 2020 Étienne de Montety LA GRANDE ÉRIUM 2019 Laurent Binet CIVILIZATIONS 2018 Camille Pascal L'ÉTÉ DES QUATRE ROIS 2017 Daniel Rondeau MÉCANIQUES DU CHAOS 2016 Adelaïde de Clermont-Tonnerre LE DERNIER DES NÔTRES 2015 Hédi Kaddour LES PRÉPONDÉRANTS Boualem Sansal 2084: LA FIN DU MONDE 2014 Adrien Bosc CONSTELLATION 2013 Christophe Ono-dit-Biot PLONGER 2012 Joël Dicker LA VÉRITÉ SUR L'AFFAIRE HARRY QUEBERT (Resnica o aferi Harry Quebert, 2015) 2011 Sorj Chalandon RETOUR À KILLYBEGS 2010 Éric Faye NAGASAKI 2009 Pierre Michon LES ONZE 2008 Marc Bressant LA DERNIÈRE CONFÉRENCE 2007 Vassilis Alexakis AP. J.-C. 2006 Jonathan Littell LES BIENVEILLANTES (Sojenice, 2010) 2005 Henriette Jelinek LE DESTIN DE IOURI VORONINE 2004 Bernard du Boucheron COURT SERPENT 2003 Jean-Noël Pancrazi TOUT EST PASSÉ SI VITE 2002 Marie Ferranti LA PRINCESSE DE MANTOUE 2001 Éric Neuhoff UN BIEN FOU 2000 Pascal Quignard TERRASSE À ROME (Terasa v Rimu, 2001) 1999 François Taillandier ANIELKA 1999 Amélie Nothomb STUPEUR ET TREMBLEMENTS (S strahospoštovanjem, 2001) 1998 Anne Wiazemsky UNE POIGNÉE DE GENS 1997 Patrick Rambaud LA BATAILLE 1996 Calixte Belaya LES HONNEURS PERDUS 1995 Alphonse Boudard MOURIR -

Literary Translation

Literary Translation 1. Dionysia Press Ltd, UK Books: 1. The Density of Now; Alexis Stamatis (GR to EN) 2. Raising of the Soul, On the Salty Earth, From the Ends of the Earth; Byron Leodaris (GR to EN) 3. 15 October 1960, The secret burial of Eleanor Tilsen; Nikos Davetas (GR to EN) 4. Hold Hands among the Atoms, Demon; Edwin Morgan (EN to GR) 5. Like Words, The Body without a Passkey; Zefi Daraki (GR to EN) Community funding: € 44.579 2. IBERBOREA, IT Books: 1. Gramosinn Gloir; Thor Vilhjalmsson (ISL to IT) 2. I Brokiga Namnet; Torgny Lindgren (SW to IT) 3. Iloisen Kotiinpaluun Asuinsijat; Leena Lander (FI to IT) 4. Popularmusik fran vittula; Nikael Niemi (SW to IT) Community funding: € 13.903 3. Norstedts Förlag, SE Books: 1. Vandrehistorier; John Erik Riley (NO to SW) 2. Sejd; Suzanne Brogger (DA to SW) 3. Galyanaplo; Imre Kertesz (HU to SW) 4. Requiem pour l’est; Andrei Makine (FR to SW) Community funding: € 20.667 4. PAX FORLAG, NO Books: 1. The Biographer’s Tale; A.S. Byatt (EN to NO) 2. The Rotter’s Club; Jonathan Coe (EN to NO) 3. L’Enfant du Peuple Ancien; Anouar Benmalek (FR to NO) 4. Det rigtige; Vibeke Gronfeldt (DA to NO) 5. Tristanakkord; Hans-Ulrich Treichel (DE to NO) 6. Popularmusik fran Vittula; Mikael Niemi (SW to NO) Community funding: € 37.521 5. Rabén & Sjögren Bokförlag, SE Books: 1. Icke naken, Icke klett; Torun Lian (NO to SW) 2. Witch Child; Celia Rees (EN to SW) 3. Charmed; Diana Jones (EN to SW) 4. -

Anniversaire Du Grand Prix Du Roman

100e ANNIVERSAIRE DU GRAND PRIX DU ROMAN DOSSIER DE PRESSE Académie française Contact : 23, quai de Conti Secrétariat de l’Académie française 75006 Paris tél : 01-44-41-43-00 www.academie-francaise.fr [email protected] SOMMAIRE § PETIT HISTORIQUE Ø La création p. 3 Ø Les particularités des premiers prix et leur empreinte p. 3 Ø Délibérations et attribution du prix de 1915 à 1960 p. 4 Ø L’organisation des années 1960 p. 5 Ø Le règlement de 1984 p. 6 Ø Règles et usage des règles de 1985 à nos jours p. 7 Encadré : Le Prix du roman en quelques dates p. 7 § L’ATTRIBUTION ACTUELLE DU GRAND PRIX DU ROMAN p. 8 Encadré : Définition, règlement, modalités de vote p. 9 § LES CENT DEUX LAURÉATS Ø Palmarès p. 10 Ø Destinées académiques p. 13 Ø Autres récompenses littéraires des lauréats p. 14 Ø Quelques particularités (Prix Nobel, âge des lauréats, répartition homme/femme, premiers romans, nationalité des lauréats) p. 16 DATES À RETENIR § Attribution du Grand Prix du roman du centenaire : le jeudi 29 octobre 2015 § Table ronde sur l’histoire du Prix à la Fondation Singer-Polignac : le mardi 20 octobre 2015. PETIT HISTORIQUE Ø La création Le Prix du roman de l’Académie française, dont le projet de création date de mars 1914, a été décerné pour la première fois en juillet 1915. Pareilles dates seraient très surprenantes si elles ne résultaient d’un processus antérieur. Il faut remonter quatre à cinq ans plus tôt. À ce moment-là, l’Académie française vient de bénéficier de deux legs importants (les legs Charruau et Broquette- Gonin) dont les revenus sont en tout ou partie librement disponibles. -

20 Ans De Notes De Lectures, Liste De La Plus Récente À La Plus Ancienne

De septembre 2000 à septembre 2020 : 20 ans de notes de lectures, liste de la plus récente à la plus ancienne Avant que j'oublie, d'Anne Pauly, Verdier. (03/09/2020) Des oloés, espaces élastiques où lire où écrire, Anne Savelli, Publie.net (27/08/2020) Le lion, de Joseph Kessel, Pléiade, tome II. (19/08/2020) Anna Karénine et Résurrection, de Léon Tolstoï, Pléiade (12/08/2020) Leurs enfants après eux, de Nicolas Mathieu, Actes Sud. (11/07/2020) La guerre et la paix, de Léon Tolstoï, Pléiade. (30/06/2020) Profession romancier, d'Haruki Murakami, Belfond. (04/06/2020) Couleurs de l'incendie, de Pierre Lemaitre, Albin Michel (28/05/2020) En Croatie et en Bosnie habsbourgeoises, d'Amédée de Caix de Saint-Amour et d'Édouard Marbeau, éditions Non Lieu. (21/05/2020) Jésus et Tito, de Vélibor Colic, Gaïa. (13/05/2020) Daewoo, de François Bon, Fayard. (16/03/2020) Caisse claire, d'Antoine Emaz, Points Seuil (02/03/2020) Propriété privée, Julia Deck, éditions de Minuit. (20/02/2020) Le livre des questions, de Pablo Neruda, La rose détachée et autres poèmes, Gallimard. (05/02/2020) Claude Simon, de Patrick Longuet, ADPF. (28/01/2020) 1 Ça raconte Sarah, de Pauline Delabroy-Allard, éditions de Minuit. (22/01/2020) L'acacia, de Claude Simon, Pléiade, volume II. (13/01/2020) Les idéaux, d'Aurélie Filippetti, Fayard. (06/01/2019) André Breton, quelques aspects de l'écrivain, Julien Gracq, Pléiade vol.1. (17/12/2019) Anthologie de poésie haïtienne contemporaine, dirigée et présentée par James Noël, Points. -

Pascal Quignard

Studi Francesi Rivista quadrimestrale fondata da Franco Simone 181 (LXI | I) | 2017 PASCAL QUIGNARD: LES "PETITS TRAITES" AU FIL DE LA RELECTURE - sous la direction de Mireille Calle-Gruber, Stefano Genetti et Chantal Lapeyre Anno LXI - fascicolo I - gennaio-aprile 2017 Edizione digitale URL: http://journals.openedition.org/studifrancesi/6164 DOI: 10.4000/studifrancesi.6164 ISSN: 2421-5856 Editore Rosenberg & Sellier Edizione cartacea Data di pubblicazione: 1 marzo 2017 ISSN: 0039-2944 Notizia bibliografica digitale Studi Francesi, 181 (LXI | I) | 2017, « PASCAL QUIGNARD: LES "PETITS TRAITES" AU FIL DE LA RELECTURE - sous la direction de Mireille Calle-Gruber, Stefano Genetti et Chantal Lapeyre » [Online], online dal 01 avril 2017, consultato il 18 septembre 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ studifrancesi/6164 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/studifrancesi.6164 Studi Francesi è distribuita con Licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione - Non commerciale - Non opere derivate 4.0 Internazionale. SOMMARIO Anno LXI – fasc. I – gennaio-aprile 2017 PASCAL QUIGNARD: LES “PETITS TRAITÉS” AU FIL DE LA RELECTURE sous la direction de MIREILLE CALLE-GRUBER, STEFANO GENETTI et CHANTAL LAPEYRE MIREILLE CALLE-GRUBER, STEFANO GENETTI et CHANTAL LAPEYRE, Introduction, p. 3. PASCAL QUIGNARD, Sancta Eulalia, p. 11. JEAN-LOUIS PAUTROT, “Petits traités”, thésaurus d’une œuvre, p. 14. DOMINIQUE RABATÉ, Réflexion et aveuglement dans les “Petits traités”, p. 24. BRUNO BLANCKEMAN, La folle étude, p. 33. SAÏDA ARFAOUI, Penser l’amitié avec Pascal Quignard. De “Petits traités” à “Leçons de solfège et de piano”, p. 40. CHANTAL LAPEYRE, “Petits traités” du ravissement. Lire Pascal Quignard avec Marguerite Duras, p. 49. ANNA MARIA BABBI, Le Moyen Âge français dans les “Petits traités”, p. -

Du Prix Des Lycéens Goncourt

DossierDoossier ded presseprresse La Fnac et le ministère en charge de l’Éducation nationale célèbrent la 27e DU PRIX GONCOURT DES LYCÉENS *Le Prix Goncourt des Lycéens est organisé par le ministère en charge de l’Education nationale et la Fnac, en accord avec l’Académie Goncourt et d’après sa sélection Présentation DU PRIX GONCOURT DES LYCÉENS La Fnac, 1er libraire de France, et le ministère en charge de l’Éducation nationale, avec l’Académie Goncourt, présentent cette année la 27e édition du Prix Goncourt des Lycéens. Véritable vecteur culturel depuis plus d’un quart de siècle, ce Prix unique en France entraîne chaque année plus de 2000 lycéens et leurs équipes pédagogiques dans une aventure littéraire hors norme, placé sous le signe de l’enthousiasme, de la spontanéité et de la transmission culturelle. Par véritable passion voire défi personnel, ces lycéens s’engagent, étudient et défendent avec ferveur, leurs coups de cœur littéraires, en classe avec leurs professeurs, mais également avec les auteurs de la sélection Goncourt, dans le cadre de rencontres régionales organisées par la Fnac et le ministère en charge de l’Education nationale. Sorj CHALANDON # Prix Goncourt des Lycéens 2013 pour « Le quatrième mur ». Extrait de la lettre adressée aux lycéens : Ce prix est de pur cristal, sans calcul ni pression, sans aspérité ni défaut. Votre choix est un honneur. [...] Mais pour vous, c’est maintenant que tout commence. Pendant deux mois, tous avez lu ou parcouru les quinze romans en lice, avec vos propres exigences et vos propres désirs. Vous avez débattu, écouté, appris. -

Le Roman : Hors Frontières Du Lundi 25 Mai - Au Dimanche 31 Mai 2009 Co-Réalisation Avec Dossier De Presse En Partenariat Avec

LE ROMAN : HORS FRONTIÈRES DU LUNDI 25 MAI - AU DIMANCHE 31 MAI 2009 co-réalisation avec DOSSIER DE PRESSE en partenariat avec Aux Subsistances - 8, bis quai Saint-Vincent - Lyon 1er Réservations : 04 78 39 10 02 - www.villagillet.net Les Assises Internationales du Roman - 3e édition Un événement conçu et organisé par et la « Comment le roman nous parle-t-il du monde ? De quelle façon la littérature peut- elle non seulement refléter la réalité, mais aussi, pourquoi pas, la transformer? C’est autour de ces questions que se sont dessinées les Assises Internationales du Roman, co-organisées depuis 2007 par Le Monde et la Villa Gillet. Le projet partait d’un constat très simple : le roman n’est pas mort, ni même agonisant, mais vivant, vivace et indispensable, tant du point de vue esthétique que politique, au sens large du terme. Car la littérature ne se contente pas de représenter le monde, elle l’éclaire et tente d’en percer les mystères. Elle en fait saillir les paradoxes, les profondeurs inattendues, les contradictions et les douleurs, plus clairement que beaucoup de traités. Outil de compréhension, en même temps que support de rêve, le roman est un lieu de liberté. Dès l’origine, les Assises ont été appuyées sur un postulat fondamental : il ne s’agissait pas d’organiser une énième foire du livre, où chaque auteur viendrait défendre son propre ouvrage, mais des rencontres, autour de thèmes bien précis et de textes préparés à l’avance. Discuter de littérature, en somme, plutôt que de parler-des-livres-dont-on-parle. -

The United States As Seen Through French and Italian Eyes

FANTASY AMERICA: THE UNITED STATES AS SEEN THROUGH FRENCH AND ITALIAN EYES by MARK HARRIS M.A., The University of British Columbia, 1992 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Programme in Comparative Literature) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April 1998 © Mark Robert Harris, 1998 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada DE-6 (2/88) - i i - Abstract For the past two decades, scholars have been reassessing the ways in which Western writers and intellectuals have traditionally misrepresented the non-white world for their own ideological purposes. Orientalism, Edward Said's ground-breaking study of the ways in which Europeans projected their own social problems onto the nations of the Near East in an attempt to take their minds off the same phenomena as they occurred closer to home, was largely responsible for this shift in emphasis. Fantasy America: The United States as Seen Through French and Italian Eyes is an exploration of a parallel occurrence that could easily be dubbed "Occidentalism." More specifically, it is a study of the ways in which French and Italian writers and filmmakers have sought to situate the New World within an Old World context. -

1 DISSERTATIONS in PROGRESS Compiled And

DISSERTATIONS IN PROGRESS Compiled and Edited by Madeline Turan, Stony Brook University This is the forty-ninth annual listing of doctoral dissertations from graduate programs in North America. It should be considered a supplement of preceding lists. Defended dissertations are listed as a separate section, after the “Dissertations in Progress” list. The dissertation titles are listed alphabetically under “Cultural Studies,” “Film Studies,” “Linguistics,” “Literature,” or “Pedagogy”. Literature dissertations are arranged by century and author or are listed under “General.” There is also a separate section for Francophone authors and topics. In each entry, the name of the dissertation director and that of the institution are given in parentheses. Titles are numbered consecutively within each section. Title changes are noted at the end of each section, showing the number of the dissertation as it was previously listed, followed by the new title. It should be noted that, in general, the information was compiled as submitted by each institution. We regret that titles from a few schools were not received in time for publication. DISSERTATIONS IN PROGRESS (2012) A. CULTURAL STUDIES 88. Comic Memory: Franco-Algerian Relations through Humor (1954–2012). Sandra Rousseau (Jennifer A. Boittin, Pennsylvania State University) 89. Cuisine and the French Social Imaginary: Tracing the Origins of Gastronomic Discourse in Early-19th-Century France. Maximillian Shrem (Anne Deneys- Tunney, New York University) 90. Designing Women: Fashion and Fiction in Second Empire France. Sara Phenix (Andrea Goulet, University of Pennsylvania) 91. Intellectuel résistant: l’anti-impérialisme contestataire de Claude Bourdet dans l’après-guerre. Fabrice Picon (Jennifer Boittin, Pennsylvania State University) 92. -

Human-Animal / Humain-Animal

20th/21st Century French and Francophone Studies International Colloquium Wednesday, March 30 - Saturday, April 2, 2011 The Westin St. Francis Hotel, Union Square, San Francisco HUMAN-ANIMAL / HUMAIN-ANIMAL Cheval No. 2 © J. Tomas Lopez University of San Francisco Centre national de la recherche scientifique Agence nationale de la recherche A Acknowledgements The “Human-Animal” Colloquium is sponsored by the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of San Francisco, the French National Research Agency (ANR – Project “Animots: Animals and Animality in 20th-21st Century French and Francophone Literature”), the Arts and Language Research Center (CRAL, the CNRS / EHESS), the University Sorbonne Nouvelle-Paris 3 (Team “Writings of Modernity”), and The French Consulate of San Francisco. Remerciements Le colloque « Humain-Animal » a reçu le soutien de la Faculté de Lettres et Sciences de l’Université de San Francisco, de l’Agence nationale de la recherche (ANR – Programme « Animots : animaux et animalité dans la littérature de langue française XXe-XXIe siècles »), du Centre de recherches sur les arts et le langage (CRAL, CNRS / EHESS), de l’Université Sorbonne Nouvelle-Paris 3 (Équipe « Écritures de la modernité ») et du Consulat Général de France à San Francisco. With special thanks to Audrey Lasserre for her tremendous work of organization and on the progam schedule; Dr. Lois Lorentzen, Associate Dean, and Dr. Marcelo Camperi, Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences for their generous contribution and continuing support; John Pinelli, Executive Director of the College of Arts and Sciences; Teresa Zane, Assistant Director of Financial Applications for her skills in computer technology; USF Office of Publications for their collaboration with the production of the program; Jennesis K.