Impacts on Tourism in the Karoo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Klein Karoo and Garden

TISD 21 | Port Elizabeth to Cape Town | Scheduled Guided Tour 8 30 Trip Highlights Group size GROUP DAY SUPERIOR SIZE FREESELL • Experience crossing the Storms River 8 guests per vehicle suspension bridge • Dolphin watching on an ocean safari Departure details Time: Selected Sundays • Sunset Knysna oyster cruise PE central hotels ±08h30 • Ostrich Farm tractor tour Collection times vary; are subject to the hotel collection route and will be • Olive and wine tasting confirmed, via the hotel, the day prior to departure Departure Days: Day 1 | Sunday Tour Language: German English French PORT ELIZABETH to KNYSNA via TSITSIKAMMA FOREST (±285km) Guests are collected from their hotel and head west to Knysna via Storm’s River Departure days: SUNDAYS SUNDAYS SUNDAYS and the Tsitsikamma Forest; in the heart of the Garden Route. Guests will stop November 01, 15, 29 08 22 at Storms River and enjoy a short walk to the suspension bridge to take in the December 06, 20, 27 13 – views. 2020 January 03, 24, 31 10 17 February 14, 28 07 21 Enjoy lunch (own account) in the Tsitsikamma Forest, home to century-old March 14, 21, 28 07 – trees, then continue on to the picturesque town of Knysna. April 11, 25 04 18 May 09, 16, 23 02, 30 – After arrival and check-in, guests board the informative Knysna oyster cruise to June 06, 13, 20 27 – sample oysters and enjoy a sundowner. Guests savour an evening’s dinner next 2021 July 11, 18 25 04 to the Knysna Estuary (own account). August 01, 12, 26 22 08 Overnight at Protea Hotel by Marriott Knysna Quays or similar – Breakfast. -

Groundwater Recharge Estimation in Table Mountain Group Aquifer Systems with a Case Study of Kammanassie Area

GROUNDWATER RECHARGE ESTIMATION IN TABLE MOUNTAIN GROUP AQUIFER SYSTEMS WITH A CASE STUDY OF KAMMANASSIE AREA by Yong Wu Submitted in the fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Earth Sciences Faculty of Natural Sciences University of the Western Cape Cape Town Supervisor: Prof. Yongxin Xu Co-supervisor: Dr. Rian Titus August 2005 DECLARATION I declare that GROUNDWATER RECHARGE ESTIMATION IN TABLE MOUNTAIN GROUP AQUIFER SYSTE MS WITH A CASE STUDY OF KAMMANASSIE AREA is my own work, that it has not been submitted for any degree or examination in any other university, and that all the sources I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledge by complete references. Full name: Yong Wu Date: August 2005 Signed……………. Abstract Groundwater Recharge Estimation in Table Mountain Group Aquifer Systems with a case study of Kammanassie Area Y. Wu PhD Thesis Department of Earth Sciences Key words: Hydrogeology, hydrogeochemistry, topography, Table Mountain Group, Kammanassie area, groundwater recharge processes, recharge estimation, mixing model, chloride mass balance, water balance, cumulative rainfall departure The Table Mountain Group (TMG) sandstone is a regional fractured rock aquifer system with the potential to be come the major source of future bulk water supply to meet both agricultural and urban requirements in the Western and Eastern Cape Provinces, South Africa. The TMG aquifer including Peninsula and Nardouw formations comprises approximately 4000m thick sequence of quartz arenite with outcrop area of 37,000 km 2. Groundwater in the TMG aquifer is characterized by its low TDS and excellent quality. Based on the elements of the TMG hydrodynamic system including boundary conditions of groundwater flow, geology, geomorphology and hydrology, nineteen hydrogeological units were identified, covering the area of 248,000km2. -

Tourism White Paper

WHITE PAPER THE DEVELOPMENT AND PROMOTION OF TOURISM IN SOUTH AFRICA GOVERNMENT OF SOUTH AFRICA DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL AFFAIRS AND TOURISM MAY, 1996 Table of contents Abbreviations Definition of Terms The Policy Formulation Process PART I: THE ROLE OF TOURISM IN SOUTH AFRICA 1.1 South Africa's Tourism Potential 1.2 Role in the Economy 1.3 Recent Performance PART II: THE PROBLEMATIQUE 2.1 A Missed Opportunity 2.2 Key Constraints PART III: TOWARDS A NEW TOURISM 3.1 Tourism and the RDP 3.2 Why Tourism? 3.3 Any Kind of Tourism? 3.4 Responsible Tourism 3.5 Effects of Irresponsible Tourism PART IV VISION, OBJECTIVES AND PRINCIPLES 4.1 Vision 4.2 Guiding Principles 4.3 Critical Success Factors 4.4 Key Objectives 4.5 Specific Targets PART V: IGNITING THE ENGINE OF TOURISM GROWTH 5.1 Safety and Security 5.2 Education and Training 5.3 Financing Tourism 5.4 Investment Incentives 5.5 Foreign Investment 5.6 Environmental Conservation 5.7 Cultural Resource Management 5.8 Product Development 5.9 Transportation 5.10 Infrastructure 5.11 Marketing and Promotion 5.12 Product Quality and Standards 5.13 Regional Cooperation 5.14 Youth Development PART VI: ROLES OF THE KEY PLAYERS 6.1 Role of the National Government 6.2 Role of the Provincial Government 6.3 Role of Local Government 6.4 Role of the Private Sector 6.5 Role of Labour 6.6 Role of Communities 6.7 Role of Women 6.8 Role of NGOs 6.9 Role of the Media 6.10 Role of Conservation Agencies PART VII ORGANISATIONAL STRUCTURE 7.1 Ministry of Environmental Affairs and Tourism 7.1.1 Department of Environmental -

South Africa Motorcycle Tour

+49 (0)40 468 992 48 Mo-Fr. 10:00h to 19.00h Good Hope: South Africa Motorcycle Tour (M-ID: 2658) https://www.motourismo.com/en/listings/2658-good-hope-south-africa-motorcycle-tour from €4,890.00 Dates and duration (days) On request 16 days 01/28/2022 - 02/11/2022 15 days Pure Cape region - a pure South Africa tour to enjoy: 2,500 kilometres with fantastic passes between coastal, nature and wine-growing landscapes. Starting with the world famous "Chapmans Peak" it takes as a start or end point on our other South Africa tours. It is us past the "Cape of Good Hope" along the beautiful bays situated directly on Beach Road in Sea Point. Today it is and beaches around Cape Town. Afterwards the tour runs time to relax and discover Cape Town. We have dinner through the heart of the wine growing areas via together in an interesting restaurant in the city centre. Franschhoek to Paarl. Via picturesque Wellington and Tulbagh we pass through the fruit growing areas of Ceres Day 3: to the Cape of Good Hope (Winchester Mansions to the enchanted Cederberg Mountains. The vastness of Hotel) the Klein Karoo offers simply fantastic views on various Today's stage, which we start right after the handover and passes towards Montagu and Oudtshoorn. Over the briefing on GPS and motorcycles, takes us once around the famous Swartberg Pass we continue to the dreamy Prince entire Cape Peninsula. Although the round is only about Albert, which was also the home of singer Brian Finch 140 km long, there are already some highlights today. -

Tourism Remains a Key Driver of South Africa's National Economy And

Tourism remains a key driver of South Africa’s national economy and contributes to job creation. The tourism industry is a major contributor to the South African economy and employment of citizens. The sector contributes about 9% to the country’s gross domestic product (GDP). The National Tourism Sector Strategy (NTSS) seeks to increase tourism’s total direct and indirect contribution to the economy from R189,4 billion in 2009 to R318,2 billion in 2015 and R499 billion in 2020. During 2016, 2 893 268 tourists arrived in South through air, 7 139 580 used road transport and 11 315 used sea transport. The majority of tourists, 9 706 602 (96,6%) were on holiday compared to 255 932 (2,5%) and 81 629 (0,8%) who came for business and study purposes respectively. The highest increase, 38,1% was for tourists from China (from 84 691 in 2015 to 116 946 in 2016), followed by India, 21,7% (from 78 385 in 2015 to 95 377 in 2016) and Germany, 21,5% (from 256 646 in 2015 to 311 832 in 2016). Tourists from Southern African Development Community Community countries (7 313 684) increased by 11,2%, from 6 575 244 in 2016. The highest increase, 26,0% was for tourists from Lesotho (from 1 394 913 in 2015 to 1 757 058 in 2016), followed by Botswana, 14,5% (from 593 514 in 2015 to 679 828 in 2016). The number of tourists from ‘other’ African countries (increased by 9,9% from 170 870 in 2015 to 187 828 in 2016. -

Tourism As a Driver of Peace Contents 1

TOURISM AS A DRIVER OF PEACE CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 TOURISM AS A 2. KEY FINDINGS 2 3. METHODOLOGY AT A GLANCE - MEASURING TOURISM AND PEACE 2 DRIVER OF PEACE 4. THE LINK BETWEEN TOURISM, VIOLENCE, AND CONFLICT 5 QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS ON THE LINK Trends in Tourism, Violence, and Conflict 6 BETWEEN PEACE AND TOURISM Risers and Fallers in Tourism, Violence, and Conflict 9 MAY 2016 Two Cases Compared: Poland and Nigeria 12 Tourism as a Force for Negative Peace 12 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5. THE LINK BETWEEN TOURISM AND POSITIVE PEACE 13 Over the last decade the world has become increasingly unequal in terms of its levels of Trends in Tourism and Positive Peace 15 peacefulness, with the most peaceful countries enjoying increasing levels of peace and prosperity, while the least peaceful countries are spiralling into violence and conflict. The economic costs of Risers and Fallers in in Tourism and Positive Peace 17 violence containment on the global economy are also significant and have increased, estimated at $13.7 trillion in 2012 and $14.3 trillion in 2014, or 13.4% of world GDP1. At the same time, tourism’s Two Cases Compared: Saudi Arabia and Angola 20 contribution to GDP has been growing at a global average of 2.3% since 2005, while foreign spending on tourism measured as visitor exports has been growing at a rate of 3.4% on average Tourism as a Force for Positive Peace 21 globally. Additionally, international passenger arrivals around the world have increased from a global average of 828 million in 2005 to 1.184 billion in 2015. -

Ltd Erven 194, 208, 209, 914, 915 & 1764 Blanco

JO 3 4 E 1 1 1 1807 44 9 3 307 3068 7 1790 1 1822 3 1828 1 0 645 0 H 1390 3075 07 1 070 2245 L 8 L 0 6 6 8 2 3 6 5 9 2 2 12 1 4 4 N 6 7 2 4 9 1 2246 3 0 306 R 8 1 E 7 6 6 1 K 6 1 9 1819 2 8 7 1 3 1 A 1 4 4 R 0 5 7 7 8 5 3 K 1 3 4 1 3663 6 9 E 2 0 4 6 E 1 3 9 1 1 6 N 1 6 2 T4 3 3 3069 3 S 8 9I 8 1 Z6 07 073 1 1491 1 2 7 1 3 26 4 E 4 7 8 K1 1 2 6 N 5 9 1 2 8 8 3 3076 096 4 1492 8 1 3 9 4 3 2 9 1789 1 2 6 4 8 3 7 3 3 6 0 3 1 30 3 8 2 1 2 0 0 3 1833 7 1 4 4 1840 8 1 2 5 6 9 1 893 1 5 7 3 0 6 3 5 1 0 0 76 1 5 8 2 1 4 6 3 3 0 2 1 3 1841 4 1 53 3 9 8 1814 1 6 5 1 2 0 3 94 8 8 8 3 1 3 1 3 1 2 3 8 3472 7 1 8 0 2 3063 0 0 8 3 0 7 5 1 3 2 5 8 2 3 5 95 1 8 5 4 8 5 5 2 3 3903 1 3 8 7 1 0 5 7 3095 3 8 6 3 7 0 9 0 3 0 2 9 3 4 5 0 3713 1 7 7 8 G 5 3 7 3 3 5 2 30 0 3 662 2 E 0 5 1 7 9 E 1 2 3 2 0 L 8 6 7 1 5 O 5 3 9 37 3 1 7 7 6 R 1 1 R 1 6 1819 33 1 7 G 4 A 2 1 1 1 1 7 E 22 E 1 4 1739 7 1179 1 30 3 7 7 3 9 2892 8 2 S 3 4 9 1 3 17 7 5 2891 5 5 96 1 6 8 7 1 4 3 35 7 0 5 86 1 0 2 8 0 225 7 7 7 1 6 1 4 1 3 7 12 4 6 7 6 6 B 5 440 1 7 3 1 1 6 944O 4 139 1 7 6 6 S 6 1 7 7 1 2 H513 1 8 167 1 9 0 6 5 226 9 O 5 6 1 6 6 4 6 6 8 7 5 7 F 1 2 4 F 3 7 0 U 7 8 2 3667 0 9 I 1 8 9 2 9 1 6 1 T2 2 8 8 6 S8 4 2 0 4 84 99 2 7 2 P 0 8 142 3 4 2 2235 5 1 6 1 2 A1 2 3 9 1 0 N2 2 6 9 6 4 6 9 9 4 8 2 7 3026 4 944 4 0 8 2220 4 3 2237 6 S 6 5 4 8 2 8 1 2 9 7 4 3 0 2 2 Y 7 5 101 2 0 9 1 8 1 5 2 8 N 62 7 4 3 6 3 6 16A8 0 2 0 5 3 2 7 1 17 83 3 1 8 1 5 4 143 29 2 3 4 5 2 0 9 169 1 8 1 5 81 2 3 1 5 1 0 2 9 6 2 8 1 5 2 82 5 0 3 9 5 8 4 3 5 2 6 102 1 5 4 9 6 2 106 2 2 1 P1 2 4 3032 3050 -

Destination Guide Spectacular Mountain Pass of 7 Du Toitskloof, You’Ll See the Valley and Surrounding Nature

discover a food & wine journey through cape town & the western cape Diverse flavours of our regions 2 NIGHTS 7 NIGHTS Shop at the Aloe Factory in Albertinia Sample craft goods at Kilzer’s permeate each bite and enrich each sip. (Cape Town – Cape Overberg) (Cape Town – Cape Overberg and listen to the fascinating stories Kitchen Cook and Look, (+-163kms) – Garden Route & Klein Karoo) of production. Walk the St Blaize Trail The Veg-e-Table-Rheenendal, Looking for a weekend break? Feel like (+-628kms) in Mossel Bay for picture perfect Leeuwenbosch Factory & Farm store, a week away in an inspiring province? Escape to coastal living for the backdrops next to a wild ocean. Honeychild Raw Honey and Mitchell’s We’ve made it easy for you. Discover weekend. Within two hours of the city, From countryside living to Nature’s This a popular 13.5 km (6-hour) hike Craft Beer. Wine lover? Bramon, Luka, four unique itineraries, designed to you’ll reach the town of Hermanus, Garden. Your first stop is in the that follows the 30 metre contour Andersons, Newstead, Gilbrook and help you taste the flavours of our city the Whale-Watching Capital of South fruit-producing Elgin Valley in the along the cliffs. It begins at the Cape Plettenvale make up the Plettenberg and 5 diverse regions. Your journey is Africa. Meander the Hermanus Wine Cape Overberg, where you can zip-line St. Blaize Cave and ends at Dana Bay Bay Wine Route. It has recently colour-coded, so check out the icons Route to the wineries situated on an over the canyons of the Hottentots (you can walk it in either direction). -

Proquest Dissertations

FROM POLITICAL VIOLENCE TO CRIMINAL VIOLENCE - THE CASE OF SOUTH AFRICA by Sydney M. Mitchell Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia April 2006 © Copyright by Sydney M. Mitchell, 2006 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-44089-6 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-44089-6 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

South African Tourism Annual Report 2018 | 2019

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 | 2019 GENERAL INFORMATIONSouth1 African Tourism Annual Report 2018 | 2019 CELEBRATING 25 YEARS OF TOURISM 2 ANNUAL REPORT 2018 | 2019 GENERAL INFORMATION TABLE OF CONTENTS PART A: GENERAL INFORMATION 5 Message from the Minister of Tourism 15 Foreword by the Chairperson 18 Chief Executive Officer’s Overview 20 Statement of Responsibility for Performance Information for the Year Ended 31 March 2019 22 Strategic Overview: About South African Tourism 23 Legislative and Other Mandates 25 Organisational Structure 26 PART B: PERFORMANCE INFORMATION 29 International Operating Context 30 South Africa’s Tourism Performance 34 Organisational Environment 48 Key Policy Developments and Legislative Changes 49 Strategic Outcome-Oriented Goals 50 Performance Information by Programme 51 Strategy to Overcome Areas of Underperformance 75 PART C: GOVERNANCE 79 The Board’s Role and the Board Charter 80 Board Meetings 86 Board Committees 90 Audit and Risk Committee Report 107 PART D: HUMAN RESOURCES MANAGEMENT 111 PART E: FINANCIAL INFORMATION 121 Statement of Responsibility 122 Report of Auditor-General 124 Annual Financial Statements 131 CELEBRATING 25 YEARS OF TOURISM ANNUAL REPORT 2018 | 2019 GENERAL INFORMATION 3 CELEBRATING 25 YEARS OF TOURISM 4 ANNUAL REPORT 2018 | 2019 GENERAL INFORMATION CELEBRATING 25 YEARS OF TOURISM ANNUAL REPORT 2018 | 2019 GENERAL INFORMATION 5 CELEBRATING 25 YEARS OF TOURISM 6 ANNUAL REPORT 2018 | 2019 GENERAL INFORMATION SOUTH AFRICAN TOURISM’S GENERAL INFORMATION Name of Public Entity: South African Tourism -

(B) and (O) of the Mossel Bay Land Use

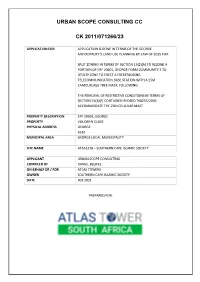

URBAN SCOPE CONSULTING CC CK 2011/071266/23 APPLICATION FOR APPLICATION IS DONE IN TERMS OF THE GEORGE MUNICIPALITY’S LAND USE PLANNING BY-LAW OF 2015 FOR: SPLIT ZONING IN TERMS OF SECTION 15(2)(A) TO REZONE A PORTION OF ERF 20601, GEORGE FORM COMMUNITY 2 TO UTILITY ZONE TO ERECT A FREESTANDING TELECOMMUNICATION BASE STATION WITH A 25M CAMOUFLAGE TREE MAST, FOLLOWING THE REMOVAL OF RESTRICTIVE CONDITIONS IN TERMS OF SECTION 15(2)(F) CONTAINED IN DEED T68235/2005 ACCOMMODATE THE 25M CELLULAR MAST PROPERTY DESCRIPTION ERF 20601, GEORGE PROPERTY VOLKWYN CLOSE PHYSICAL ADDRESS GEORGE 6530 MUNICIPAL AREA GEORGE LOCAL MUNICIPALITY SITE NAME ATSA1278 – SOUTHERN CAPE ISLAMIC SOCIETY APPLICANT URBAN SCOPE CONSULTING COMPILED BY DANIEL BEUKES ON BEHALF OF / FOR ATLAS TOWERS OWNER SOUTHERN CAPE ISLAMIC SOCIETY DATE FEB 2021 PREPARED FOR: Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................. 3 2. NATURE OF THIS APPLICATION ..................................................................................................... 3 2.1 Consent Use [In Accordance to Section 15(2)(o)].................................................................. 3 2.2 Permanent Departure [In Accordance to Section 15(2)(b)]................................................... 4 3. GENERAL INFORMATION .............................................................................................................. 4 3.1 LOCATION ............................................................................................................................ -

Youth Tourism in South Africa: the English Language Travel Sector

Tourism Review International, Vol. 15, pp. 123–133 1544-2721/11 $60.00 + .00 Printed in the USA. All rights reserved. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3727/154427211X13139345020453 Copyright © 2011 Cognizant Comm. Corp. www.cognizantcommunication.com YOUTH TOURISM IN SOUTH AFRICA: THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE TRAVEL SECTOR MAISA CORREIA Department of Tourism Management, School of Tourism and Hospitality, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa Language travel has gone largely unnoticed as a key contributor of youth tourism. The global lan- guage travel market is dominated by the UK and the US, with Canada, Australia, Ireland, Malta, and New Zealand also recognizing the importance of language travel for tourism. Little attention has been paid to language travel in research, including in South Africa. This article reviews the organiza- tion and development of the language travel industry in South Africa as an important aspect of the country’s youth tourism economy. South Africa’s language travel industry is explored in terms of its global position, development, size, key role players, structure, operation, and significance for the broader tourism industry. It is shown significant differences exist in the operation and source markets between inland and coastal language schools. Key words: Language travel; Youth tourism; South Africa Introduction national arrivals and valued at approximately US$136–139 billion. The number of youth travel- Until recently youth tourism has been acknowl- ers is expected to more than double to 300 million edged as the “poor relation of international tour- arrivals by 2020 (Jones, 2008; United National ism” (Richards & Wilson, 2005, p. 39). It has World Tourism Organization [UNWTO], 2008).