Green Politics at an Impasse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HON. GIZ WATSON B. 1957

PARLIAMENTARY HISTORY ADVISORY COMMITTEE AND STATE LIBRARY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA TRANSCRIPT OF AN INTERVIEW WITH HON. GIZ WATSON b. 1957 - STATE LIBRARY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA - ORAL HISTORY COLLECTION DATE OF INTERVIEW: 2015-2016 INTERVIEWER: ANNE YARDLEY TRANSCRIBER: ANNE YARDLEY DURATION: 19 HOURS REFERENCE NUMBER: OH4275 COPYRIGHT: PARLIAMENT OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA & STATE LIBRARY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA. GIZ WATSON INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPTS NOTE TO READER Readers of this oral history memoir should bear in mind that it is a verbatim transcript of the spoken word and reflects the informal, conversational style that is inherent in such historical sources. The Parliament and the State Library are not responsible for the factual accuracy of the memoir, nor for the views expressed therein; these are for the reader to judge. Bold type face indicates a difference between transcript and recording, as a result of corrections made to the transcript only, usually at the request of the person interviewed. FULL CAPITALS in the text indicate a word or words emphasised by the person interviewed. Square brackets [ ] are used for insertions not in the original tape. ii GIZ WATSON INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPTS CONTENTS Contents Pages Introduction 1 Interview - 1 4 - 22 Parents, family life and childhood; migrating from England; school and university studies – Penrhos/ Murdoch University; religion – Quakerism, Buddhism; countryside holidays and early appreciation of Australian environment; Anti-Vietnam marches; civil-rights movements; Activism; civil disobedience; sport; studying environmental science; Albany; studying for a trade. Interview - 2 23 - 38 Environmental issues; Campaign to Save Native Forests; non-violent Direct Action; Quakerism; Alcoa; community support and debate; Cockburn Cement; State Agreement Acts; campaign results; legitimacy of activism; “eco- warriors”; Inaugural speech . -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Influence on the U.S. Environmental Movement

Australian Journal of Politics and History: Volume 61, Number 3, 2015, pp.414-431. Exemplars and Influences: Transnational Flows in the Environmental Movement CHRISTOPHER ROOTES Centre for the Study of Social and Political Movements, School of Social Policy, Sociology and Social Research, University of Kent, Canterbury, UK Transnational flows of ideas are examined through consideration of Green parties, Friends of the Earth, and Earth First!, which represent, respectively, the highly institutionalised, the semi- institutionalised and the resolutely non-institutionalised dimensions of environmental activism. The focus is upon English-speaking countries: US, UK and Australia. Particular attention is paid to Australian cases, both as transmitters and recipients of examples. The influence of Australian examples on Europeans has been overstated in the case of Green parties, was negligible in the case of Friends of the Earth, but surprisingly considerable in the case of Earth First!. Non-violent direct action in Australian rainforests influenced Earth First! in both the US and UK. In each case, the flow of influence was mediated by individuals, and outcomes were shaped by the contexts of the recipients. Introduction Ideas travel. But they do not always travel in straight lines. The people who are their bearers are rarely single-minded; rather, they carry and sometimes transmit all sorts of other ideas that are in varying ways and to varying degrees discrepant one with another. Because the people who carry and transmit them are in different ways connected to various, sometimes overlapping, sometimes discrete social networks, ideas are not only transmitted in variants of their pure, original form, but they become, in these diverse transmuted forms, instantiated in social practices that are embedded in differing institutional contexts. -

The Electoral Geography of European Radical Left Parties Since 1990

‘Red Belts’ anywhere? The electoral geography of European radical left parties since 1990 Petar Nikolaev Bankov, BA, MSc Submitted in the fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Social and Political Sciences College of Social Sciences University of Glasgow January 2020 Abstract European radical left parties (RLPs) are on the rise across Europe. Since 1990 they became an integral part of the party systems across the continent and enjoy an increased level of government participation and policy clout. The main source for this improved position is their increasing electoral support in the past three decades, underpinned by a diversity of electoral geographies. Understood as the patterns of territorial distribution of electoral support across electoral units, the electoral geographies are important, as they indicate the effects of the socio-economic and political changes in Europe on these parties. This thesis studies the sources of the electoral geographies of European RLPs since 1990. The existing literature on these parties highlighted the importance of their electoral geographies for understanding their electoral and governmental experiences. Yet, to this date, it lacks systematic research on these territorial distributions of electoral support in their own right. Such research is important also for the general literature on the spatial distribution of electoral performance. In particular, these works paid limited attention to the relevance of their theories for individual political parties, as they -

Take Heart and Name WA's New Federal Seat Vallentine 2015 Marks 30 Years Since Jo Vallentine Took up Her Senate Position

Take heart and name WA’s new federal seat Vallentine 2015 marks 30 years since Jo Vallentine took up her senate position, the first person in the world to be elected on an anti-nuclear platform. What better way to acknowledge her contribution to peace, nonviolence and protecting the planet than to name a new federal seat after her? The official Australian parliament website describes Jo Vallentine in this way: Jo Vallentine was elected in 1984 to represent Western Australia in the Senate for the Nuclear Disarmament Party, running with the slogan ‘Take Heart—Vote Vallentine’. She commenced her term in July 1985 as an Independent Senator for Nuclear Disarmament, claiming in her first speech that she was the first member of any parliament in the world to be elected on this platform. When she stood for election again in 1990, she was elected as a senator for The Greens (Western Australia), and was the first Green in the Australian Senate. … During her seven years in Parliament, Vallentine was a persistent voice for peace, nuclear disarmament, Aboriginal land rights, social justice and the environment (emphasis added)i. Jo Vallentine’s parliamentary and subsequent career should be recognised in the named seat of Vallentine because: 1. Jo Vallentine was the first woman or person in several roles, in particular: The first person in the world to win a seat based on a platform of nuclear disarmament The first person to be elected to federal parliament as a Greens party politician. The Greens are now Australia’s third largest political party, yet no seat has been named after any of their political representatives 2. -

The Charter and Constitution of the Australian Greens May 2020 Charter

The Charter and Constitution of the Australian Greens May 2020 Charter .......................................................................................................................................................................3 Basis of The Charter ..............................................................................................................................................3 Ecology ..................................................................................................................................................................3 Democracy.............................................................................................................................................................3 Social Justice .........................................................................................................................................................3 Peace ....................................................................................................................................................................3 An Ecologically Sustainable Economy ....................................................................................................................4 Meaningful Work ....................................................................................................................................................4 Culture ...................................................................................................................................................................4 -

Challenger Party List

Appendix List of Challenger Parties Operationalization of Challenger Parties A party is considered a challenger party if in any given year it has not been a member of a central government after 1930. A party is considered a dominant party if in any given year it has been part of a central government after 1930. Only parties with ministers in cabinet are considered to be members of a central government. A party ceases to be a challenger party once it enters central government (in the election immediately preceding entry into office, it is classified as a challenger party). Participation in a national war/crisis cabinets and national unity governments (e.g., Communists in France’s provisional government) does not in itself qualify a party as a dominant party. A dominant party will continue to be considered a dominant party after merging with a challenger party, but a party will be considered a challenger party if it splits from a dominant party. Using this definition, the following parties were challenger parties in Western Europe in the period under investigation (1950–2017). The parties that became dominant parties during the period are indicated with an asterisk. Last election in dataset Country Party Party name (as abbreviation challenger party) Austria ALÖ Alternative List Austria 1983 DU The Independents—Lugner’s List 1999 FPÖ Freedom Party of Austria 1983 * Fritz The Citizens’ Forum Austria 2008 Grüne The Greens—The Green Alternative 2017 LiF Liberal Forum 2008 Martin Hans-Peter Martin’s List 2006 Nein No—Citizens’ Initiative against -

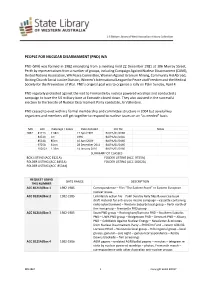

Collection Name

PEOPLE FOR NUCLEAR DISARMAMENT (PND) WA PND (WA) was formed in 1982 emanating from a meeting held 22 December 1981 at 306 Murray Street, Perth by representatives from a number of groups, including Campaign Against Nuclear Disarmament (CANE), United Nations Association, WA Peace Committee, Women Against Uranium Mining, Community Aid Abroad, Uniting Church Social Justice Division, Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom and the Medical Society for the Prevention of War. PND’s original goal was to organise a rally on Palm Sunday, April 4. PND regularly protested against the visit to Fremantle by nuclear powered warships and conducted a campaign to have the US military base at Exmouth closed down. They also assisted in the successful election to the Senate of Nuclear Disarmament Party candidate, Jo Vallentine. PND ceased to exist within a formal membership and committee structure in 2004 but several key organizers and members still get together to respond to nuclear issues on an “as needed” basis. MN ACC meterage / boxes Date donated CIU file Notes 2867 8121A 2.38m 17 April 1991 BA/PA/01/0166 8451A 1m 1996 BA/PA/01/0166 8534A 85cm 16 April 2009 BA/PA/01/0166 9725A 61cm 28 December 2011 BA/PA/01/0166 10202A 1.36m 14 January 2016 BA/PA/01/0166 SUMMARY OF CLASSES BOX LISTING (ACC 8121A) FOLDER LISTING (ACC 9725A) FOLDER LISTING (ACC 8451A) FOLDER LISTING (ACC 10202A) FOLDER LISTING (ACC 8534A) REQUEST USING DATE RANGE DESCRIPTION THIS NUMBER ACC 8121A/Box 1 1982-1985 Correspondence – File; “The Eastern Front” re Eastern European nuclear -

Leadership and the Australian Greens

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Online @ ECU Edith Cowan University Research Online ECU Publications Post 2013 1-1-2014 Leadership and the Australian Greens Christine Cunningham Edith Cowan University, [email protected] Stewart Jackson Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ecuworkspost2013 Part of the Leadership Studies Commons, and the Political Science Commons 10.1177/1742715013498407 This is an Author's Accepted Manuscript of: Cunningham, C., & Jackson, S. (2014). Leadership and the Australian Greens. Leadership, 10(4), 496-511. Reprinted by permission of SAGE Publications. Available here. This Journal Article is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ecuworkspost2013/26 Leadership and the Australian Greens Christine Cunningham School of Education, Education and the Arts Faculty, Edith Cowan University, Australia Stewart Jackson Department of Government and International Relations, Faculty of Arts, The University of Sydney, Australia Abstract This paper examines the inherent tension between a Green political party’s genesis and official ideology and the conventional forms and practices of party leadership enacted in the vast bulk of other parties, regardless of their place on the ideological spectrum. A rich picture is painted of this ongoing struggle through a case study of the Australian Greens with vivid descriptions presented on organisational leadership issues by Australian state and federal Green members of parliaments. What emerges from the data is the Australian Green MPs’ conundrum in retaining an egalitarian and participatory democracy ethos while seeking to expand their existing frame of leadership to being both more pragmatic and oriented towards active involvement in government. -

The Australian Greens' Election Policies

THE AUSTRALIAN GREENS’ ELECTION POLICIES Why The Greens’ Policies Matter by Jim Hoggett An IPA Electronic Backgrounder September 2004 THE AUSTRALIAN GREENS’ ELECTION POLICIES 1 THE AUSTRALIAN GREENS’ ELECTION POLICIES Why The Greens’ Policies Matter Executive Summary • Green policies now matter as their voter base grows, their parliamentary power increases and their policy ambit widens. • Contrary to popular perception their policies are not narrowly environmental – in their entirety they mimic the central planning model now rejected by all but a few closed societies. • Their environmental policies are based on quasi-religious belief and serious misconceptions of the quality and resilience of the environment – they will strike particularly hard at the rural sector. • Green economic policies will radically redistribute the shrinking national income their policies will bring about. • Investment controls, weak labour policies and other forms of interference in markets will destabilise the economy. • Energy consumption and exports will be drastically reduced by quarantining our principal energy source, coal, and any other feasible alternative. • Wind, solar and other renewables can replace only a fraction of current supply at a much higher cost – they will enforce negative economic growth. • Immigration policy will focus on facilitating the entry of refugees and restricting the current flow of skilled and highly educated immigrants. • Other policies will enlarge the public sector, tighten censorship, restrict overseas trade and liberal- ise drug use. • Twenty or more new or increased taxes are proposed to reduce incomes, increase prices, tax in- heritances and shrink the rental property pool. • Green policies will hit the poor hardest through increased taxation, high energy (and hence goods and services) prices, lower employment and economic growth and reduced choices – we will all be worse off but the poor will suffer most. -

The Dutch Parliamentary Elections: Outcome and Implications

CRS INSIGHT The Dutch Parliamentary Elections: Outcome and Implications March 20, 2017 (IN10672) | Related Author Kristin Archick | Kristin Archick, Specialist in European Affairs ([email protected], 7-2668) The March 15, 2017, parliamentary elections in the Netherlands garnered considerable attention as the first in a series of European contests this year in which populist, antiestablishment parties have been poised to do well, with possibly significant implications for the future of the European Union (EU). For many months, opinion polls projected an electoral surge for the far-right, anti-immigrant, anti-EU Freedom Party (PVV), led by Geert Wilders. Many in the EU were relieved when the PVV fell short and the center-right, pro-EU People's Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD), led by incumbent Prime Minister Mark Rutte, retained its position as the largest party in the Dutch parliament. Several commentators suggest that the Dutch outcome may be a sign that populism in Europe and "euroskeptism" about the EU are starting to lose momentum, but others remain cautious about drawing such conclusions yet. Election Results The Dutch political scene has become increasingly fragmented; 28 political parties competed in the 2017 elections for the 150-seat Second Chamber, the "lower"—but more powerful—house of the Dutch parliament. Concerns about immigration, national identity, and the role of Islam in the Netherlands (approximately 5.5% of the country's 17 million people are Muslim) dominated the campaigning. The VVD came in first, with 33 seats, but lost roughly one-fifth of its previous total. The PVV finished second, with 20 seats, making modest gains on its 2012 election results but not performing as well as expected. -

The Charter and National Constitution of the Australian Greens

The Charter and National Constitution of the Australian Greens November 2010 Definitions...................................................................................................................... 3 Definitions, Constituent Groups .................................................................................... 4 Introduction to the Constitution ..................................................................................... 5 Chapter 1 - Purpose and Charter .................................................................................... 6 1 - Name and Constitution ......................................................................................... 6 2 - Constitutions: State Parties and their Constituent Groups .................................... 6 3 - The Charter of The Greens ................................................................................... 6 4 - Objectives ............................................................................................................. 7 Chapter 2 - Membership Criteria and Appeals .............................................................. 8 5 - Member Bodies..................................................................................................... 8 6 - Obligations of Member Bodies............................................................................. 8 7 - Resignation and Expulsion of Member Bodies .................................................... 8 8 - Membership .........................................................................................................