Leadership and the Australian Greens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Procedural Digest 24 25 26 27 28

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES August/ September 2020 M T W T F Procedural Digest 24 25 26 27 28 No. 12 31 1 2 3 4 46th Parliament 24 August – 3 September 2020 Selected entries contain links to video footage via Parlview. Please note that the first time you click a [Watch] link, you may need to refresh the page (ctrl+F5) for the correct starting point. Bills 12.01 Jobkeeper bill introduced and passed all stages in one sitting The Treasurer presented the Coronavirus Economic Response Package (Jobkeeper Payments) Amendment Bill 2020 on 26 August. In his second reading speech, the Treasurer thanked the opposition for its support in progressing the bill through the parliament quickly to provide certainty to Australian businesses and employees. Following his speech, the House gave leave for the debate to be made an order of the day for a later hour. During the day, 28 members contributed to the second reading debate. At the conclusion of the debate, a second reading amendment moved by the shadow Treasurer was negatived on division and the question ‘that the bill be read a second time’ was carried on the voices. Following a message from the Governor-General recommending appropriation, the bill proceeded to the consideration in detail stage and several opposition amendments were negatived on division. Consideration in detail concluded and, by leave, an assistant minister moved the third reading. The question ‘that the bill be read a third time’ was carried on the voices. The Speaker granted the Manager of Opposition Business indulgence a number of times over the sitting fortnight to place on the record the voting intentions of independent and minor party members unable to attend the sittings due to the pandemic. -

Chronology of Same-Sex Marriage Bills Introduced Into the Federal Parliament: a Quick Guide

RESEARCH PAPER SERIES, 2017–18 UPDATED 24 NOVEMBER 2017 Chronology of same-sex marriage bills introduced into the federal parliament: a quick guide Deirdre McKeown Politics and Public Administration Section On 15 November 2017, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) announced the results of the voluntary Australian Marriage Law Postal survey. The ABS reported that, of the 79.5 per cent of Australians who expressed a view on the question Should the law be changed to allow same-sex couples to marry?, ‘the majority indicated that the law should be changed to allow same-sex couples to marry, with 7,817,247 (61.6 per cent) responding Yes and 4,873,987 (38.4 per cent) responding No’. On the same day Senator Dean Smith (LIB, WA) introduced, on behalf of eight cross-party co-sponsors, a bill to amend the Marriage Act 1961 (Cth) so as to redefine marriage as ‘a union of two people’. This is the fifth marriage equality bill introduced in the current (45th) Parliament, while six bills were introduced into the previous (44th) Parliament. Since the 2004 amendment to the Marriage Act 1961 (Cth) which inserted the current definition of marriage, 23 bills dealing with marriage equality or the recognition of overseas same-sex marriages have been introduced into the federal Parliament. Four bills have come to a vote: three in the Senate (in 2010, 2012 and 2013), and one in the House of Representatives (in 2012). These bills were all defeated at the second reading stage; consequently no bill has been debated by the second chamber. -

HON. GIZ WATSON B. 1957

PARLIAMENTARY HISTORY ADVISORY COMMITTEE AND STATE LIBRARY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA TRANSCRIPT OF AN INTERVIEW WITH HON. GIZ WATSON b. 1957 - STATE LIBRARY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA - ORAL HISTORY COLLECTION DATE OF INTERVIEW: 2015-2016 INTERVIEWER: ANNE YARDLEY TRANSCRIBER: ANNE YARDLEY DURATION: 19 HOURS REFERENCE NUMBER: OH4275 COPYRIGHT: PARLIAMENT OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA & STATE LIBRARY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA. GIZ WATSON INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPTS NOTE TO READER Readers of this oral history memoir should bear in mind that it is a verbatim transcript of the spoken word and reflects the informal, conversational style that is inherent in such historical sources. The Parliament and the State Library are not responsible for the factual accuracy of the memoir, nor for the views expressed therein; these are for the reader to judge. Bold type face indicates a difference between transcript and recording, as a result of corrections made to the transcript only, usually at the request of the person interviewed. FULL CAPITALS in the text indicate a word or words emphasised by the person interviewed. Square brackets [ ] are used for insertions not in the original tape. ii GIZ WATSON INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPTS CONTENTS Contents Pages Introduction 1 Interview - 1 4 - 22 Parents, family life and childhood; migrating from England; school and university studies – Penrhos/ Murdoch University; religion – Quakerism, Buddhism; countryside holidays and early appreciation of Australian environment; Anti-Vietnam marches; civil-rights movements; Activism; civil disobedience; sport; studying environmental science; Albany; studying for a trade. Interview - 2 23 - 38 Environmental issues; Campaign to Save Native Forests; non-violent Direct Action; Quakerism; Alcoa; community support and debate; Cockburn Cement; State Agreement Acts; campaign results; legitimacy of activism; “eco- warriors”; Inaugural speech . -

MAC1 Abstracts – Oral Presentations

Oral Presentation Abstracts OP001 Rights, Interests and Moral Standing: a critical examination of dialogue between Regan and Frey. Rebekah Humphreys Cardiff University, Cardiff, United Kingdom This paper aims to assess R. G. Frey’s analysis of Leonard Nelson’s argument (that links interests to rights). Frey argues that claims that animals have rights or interests have not been established. Frey’s contentions that animals have not been shown to have rights nor interests will be discussed in turn, but the main focus will be on Frey’s claim that animals have not been shown to have interests. One way Frey analyses this latter claim is by considering H. J. McCloskey’s denial of the claim and Tom Regan’s criticism of this denial. While Frey’s position on animal interests does not depend on McCloskey’s views, he believes that a consideration of McCloskey’s views will reveal that Nelson’s argument (linking interests to rights) has not been established as sound. My discussion (of Frey’s scrutiny of Nelson’s argument) will centre only on the dialogue between Regan and Frey in respect of McCloskey’s argument. OP002 Can Special Relations Ground the Privileged Moral Status of Humans Over Animals? Robert Jones California State University, Chico, United States Much contemporary philosophical work regarding the moral considerability of nonhuman animals involves the search for some set of characteristics or properties that nonhuman animals possess sufficient for their robust membership in the sphere of things morally considerable. The most common strategy has been to identify some set of properties intrinsic to the animals themselves. -

Green Parties and Elections to the European Parliament, 1979–2019 Green Par Elections

Chapter 1 Green Parties and Elections, 1979–2019 Green parties and elections to the European Parliament, 1979–2019 Wolfgang Rüdig Introduction The history of green parties in Europe is closely intertwined with the history of elections to the European Parliament. When the first direct elections to the European Parliament took place in June 1979, the development of green parties in Europe was still in its infancy. Only in Belgium and the UK had green parties been formed that took part in these elections; but ecological lists, which were the pre- decessors of green parties, competed in other countries. Despite not winning representation, the German Greens were particularly influ- enced by the 1979 European elections. Five years later, most partic- ipating countries had seen the formation of national green parties, and the first Green MEPs from Belgium and Germany were elected. Green parties have been represented continuously in the European Parliament since 1984. Subsequent years saw Greens from many other countries joining their Belgian and German colleagues in the Euro- pean Parliament. European elections continued to be important for party formation in new EU member countries. In the 1980s it was the South European countries (Greece, Portugal and Spain), following 4 GREENS FOR A BETTER EUROPE their successful transition to democracies, that became members. Green parties did not have a strong role in their national party systems, and European elections became an important focus for party develop- ment. In the 1990s it was the turn of Austria, Finland and Sweden to join; green parties were already well established in all three nations and provided ongoing support for Greens in the European Parliament. -

Declan Clausen [email protected] I Was

Declan Clausen [email protected] I was privileged to have recently attended the 13th annual Science Meets Parliament conference (SmP) held in Canberra as the recipient of a generous APESMA Scholarship. SmP is organised by scientific lobby group Science and Technology Australia, brings together more than 150 of Australia’s preeminent industrial and research scientists and engineers. The goal of SmP is to allow participants to discuss science with other scientists, the media, influential public servants and parliamentarians. I currently study Environmental Engineering full time at the University of Newcastle, and work part time at the Hunter Water Corporation as an Industry Scholar. Outside of University and work, I am incredibly passionate about politics and policy creation, making SmP a near perfect match for my current skills, qualifications and interest. The first day of SmP began with members of the delegation working in small groups to put together a web outlining the influences on science, politics and public policy. The remainder of the first day was spent discussing these contributing influences including discussions with a media panel, a budget officer from the Commonwealth Treasury, the Deputy Secretary of the Department of Innovation, and with a team from the Centre for Public Awareness who specialise in social media and demonstrated how the new media influences science. These activities provided a detailed insight which would provide participants with knowledge that would set the scene for the rest of the conference. The first day of SmP ended in a spectacular fashion with a formal dinner held in the Great Hall of Parliament House. -

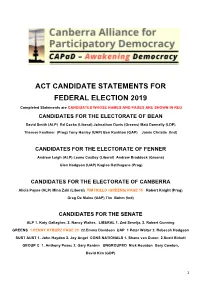

File of Candidate Statements 1

ACTwww.canberra CANDIDATE STATEMENTS-alliance.org.au FOR FEDERAL ELECTION 2019 Completed Statements are CANDIDATES WHOSE NAMES AND PAGES ARE SHOWN IN RED Responses to CANDIDATES FOR THE ELECTORATE OF BEAN [email protected] David Smith (ALP) Ed Cocks (Liberal) Johnathan Davis (Greens) Matt Donnelly (LDP) Enquiries to Bob Douglas Therese Faulkner (Prog) Tony Hanley (UAP) Ben Rushton (GAP) Jamie Christie (Ind)Tel 02 6253 4409 or 0409 233138 CANDIDATES FOR THE ELECTORATE OF FENNER Dear Dr Christie, Andrew Leigh (ALP) Leane Castley (Liberal) Andrew Braddock (Greens) Glen Hodgson (UAP) Kagiso Ratlhagane (Prog) I understand you are a candidate for the forthcoming Federal Election. CANDIDATES FOR THE ELECTORATE OF CANBERRA Congratulations, and best wishes.Alicia Payne (ALP) Mina Zaki (Liberal) TIM HOLLO (GREENS) PAGE 15 Robert Knight (Prog) Greg De Maine (UAP) Tim Bohm (Ind) I am writing on behalf of The Canberra Alliance for Participatory Democracy (CAPaD), which was formed in 2014, because many CanberransCANDIDATES were FORconcerned THE SENATE at the directions that Australian democracy was taking. ALP 1. Katy Gallagher, 2. Nancy Waites. LIBERAL 1. Zed Seselja, 2. Robert Gunning GREENS 1.PENNY KYBURZ PAGE 23 22.Emma Davidson UAP 1 Peter Walter 2. Rebecah Hodgson CAPaD seeks to enhanceSUST democracy AUST 1. John Haydon 2. Joyin Angel Canberra, CONS NATIONALS 1. Shaneso van Durenthat 2.Scott citizensBirkett can trust their elected GEOUP C 1. Anthony Pesec 2. Gary Kentnn UNGROUPED Nick Houston Gary Cowton, representatives, hold them accountable, engageDavid Kim in (GDP) decision -making, and defend what sustains the public interest. In the lead up to the 2016 ACT Legislative Assembly Elections, the major1 parties were consulted for their views about individual candidate statements, and in the light of those responses, a candidate statement was prepared, which we offered to all registered candidates for lodgement on the CAPaD website. -

Professionalization of Green Parties?

Professionalization of Green parties? Analyzing and explaining changes in the external political approach of the Dutch political party GroenLinks Lotte Melenhorst (0712019) Supervisor: Dr. A. S. Zaslove 5 September 2012 Abstract There is a relatively small body of research regarding the ideological and organizational changes of Green parties. What has been lacking so far is an analysis of the way Green parties present them- selves to the outside world, which is especially interesting because it can be expected to strongly influence the image of these parties. The project shows that the Dutch Green party ‘GroenLinks’ has become more professional regarding their ‘external political approach’ – regarding ideological, or- ganizational as well as strategic presentation – during their 20 years of existence. This research pro- ject challenges the core idea of the so-called ‘threshold-approach’, that major organizational changes appear when a party is getting into government. What turns out to be at least as interesting is the ‘anticipatory’ adaptations parties go through once they have formulated government participation as an important party goal. Until now, scholars have felt that Green parties are transforming, but they have not been able to point at the core of the changes that have taken place. Organizational and ideological changes have been investigated separately, whereas in the case of Green parties organi- zation and ideology are closely interrelated. In this thesis it is argued that the external political ap- proach of GroenLinks, which used to be a typical New Left Green party but that lacks governmental experience, has become more professional, due to initiatives of various within-party actors who of- ten responded to developments outside the party. -

Ambassade De France En Australie – Service De Presse Et Information Site : Tél

Online Press review 7 May 2015 The articles in purple are not available online. Please contact the Press and Information Department. FRONT PAGE New Greens leaders seek ‘common ground’ on reform (AUS) Crowe The Greens are promising a fresh look at major budget savings after the sudden installation of Richard Di Natale as the party’s new leader signalled a dramatic shift in power to a new generation but stirred internal rancour. Get over historical indigenous wrongs: Noel Pearson (AUS) Bita Aboriginal leader Noel Pearson has challenged indigenous Australians to get over their traumatic history in the same way that Jews survived the Holocaust. Federal budget 2015: GST on Netflix and more on the way (CAN+SMH) Martin The federal government will move to impose the goods and services tax on services such as Netflix under new rules set to be included in next week's budget. Federal budget 2015: Census saved, $250m investment in Bureau of Statistics (CAN) Martin The census has been saved and the Australian Bureau of Statistics will get a $250 million funding boost as part of the biggest technology upgrade in its 110-year history. DOMESTIC AFFAIRS POLITICS Abbott rejects slur on Paris meeting as Fairfax Media slammed (AUS) Owens Tony Abbott has denied knowing that ambassador Stephen Brady’s male partner had been instructed to leave the tarmac of a Paris airport before the Prime Minister’s arrival on Anzac Day. Smearing Tony Abbott as a homophobe is victory for hatred (AUS/Comment) Kenny Given Tony Abbott has been dubbed a misogynist, Islamophobe and racist, I suppose the - occasional allegation of homophobia shouldn’t be a surprise. -

Introduction to Volume 1 the Senators, the Senate and Australia, 1901–1929 by Harry Evans, Clerk of the Senate 1988–2009

Introduction to volume 1 The Senators, the Senate and Australia, 1901–1929 By Harry Evans, Clerk of the Senate 1988–2009 Biography may or may not be the key to history, but the biographies of those who served in institutions of government can throw great light on the workings of those institutions. These biographies of Australia’s senators are offered not only because they deal with interesting people, but because they inform an assessment of the Senate as an institution. They also provide insights into the history and identity of Australia. This first volume contains the biographies of senators who completed their service in the Senate in the period 1901 to 1929. This cut-off point involves some inconveniences, one being that it excludes senators who served in that period but who completed their service later. One such senator, George Pearce of Western Australia, was prominent and influential in the period covered but continued to be prominent and influential afterwards, and he is conspicuous by his absence from this volume. A cut-off has to be set, however, and the one chosen has considerable countervailing advantages. The period selected includes the formative years of the Senate, with the addition of a period of its operation as a going concern. The historian would readily see it as a rational first era to select. The historian would also see the era selected as falling naturally into three sub-eras, approximately corresponding to the first three decades of the twentieth century. The first of those decades would probably be called by our historian, in search of a neatly summarising title, The Founders’ Senate, 1901–1910. -

Bicameralism in the New Zealand Context

377 Bicameralism in the New Zealand context Andrew Stockley* In 1985, the newly elected Labour Government issued a White Paper proposing a Bill of Rights for New Zealand. One of the arguments in favour of the proposal is that New Zealand has only a one chamber Parliament and as a consequence there is less control over the executive than is desirable. The upper house, the Legislative Council, was abolished in 1951 and, despite various enquiries, has never been replaced. In this article, the writer calls for a reappraisal of the need for a second chamber. He argues that a second chamber could be one means among others of limiting the power of government. It is essential that a second chamber be independent, self-confident and sufficiently free of party politics. I. AN INTRODUCTION TO BICAMERALISM In 1950, the New Zealand Parliament, in the manner and form it was then constituted, altered its own composition. The legislative branch of government in New Zealand had hitherto been bicameral in nature, consisting of an upper chamber, the Legislative Council, and a lower chamber, the House of Representatives.*1 Some ninety-eight years after its inception2 however, the New Zealand legislature became unicameral. The Legislative Council Abolition Act 1950, passed by both chambers, did as its name implied, and abolished the Legislative Council as on 1 January 1951. What was perhaps most remarkable about this transformation from bicameral to unicameral government was the almost casual manner in which it occurred. The abolition bill was carried on a voice vote in the House of Representatives; very little excitement or concern was caused among the populace at large; and government as a whole seemed to continue quite normally. -

Imagereal Capture

FEDERAL DEADLOCKS : ORIGIN AND OPERATION OF SECTION 57 By J. E. RICHARDSON* This article deals with the interpretation of section 57 of the Con- stitution, and the consideration of deadlocks leading to the framing of a section at the Federal Convention Debates in Sydney in 1891 and in the three sessions held at Adelaide, Sydney and Melbourne respectively in 1897-8. It also includes a short assessment of the operation of section 57 since federation. Section 57 becomes explicable only after the nature of Senate legislative power as defined in section 53 is understood. Accordingly, the article commences by examining Senate legislative power. The two sections read: '53. Proposed laws appropriating revenue or moneys, or imposing taxation, shall not originate in the Senate. But a proposed law shall not be taken to appropriate revenue or moneys, or to impose taxation, by reason only of its containing provisions for the imposition or appropriation of fines or other pecuniary penalties, or for the demand or payment or appropriation of fees for licences, or fees for services under the proposed law. The Senate may not amend proposed laws imposing taxation, or propoaed laws appropriating revenue or moneys for the ordinary annual services of the Government. The Senate may not amend any proposed law so as to increase any pro- posed charge or burden on the people. The Senate may at any stage return to the House of Representatives any proposed law which the Senate may not amend, requesting, by message, the omission or amendment of any items or provisions therein. And the House of Representatives may, if it thinks fit, make any of such omissions or amendments, with or without modifications.