The Rise of the Australian Greens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Application to Register the Liberal Democratic Party

Review Statement giving reasons for the decision to register the Liberal Democratic Party Details of the application An application under section 89 of the Electoral Act 1992 to register the Liberal Democratic Party was received by the acting Electoral Commissioner, Ms Alison Purvis, on 19 July 2001. The application proposed that the following details be registered: Name of party: Liberal Democratic Party Abbreviation of party name: LDP Name and address of proposed registered officer: John Humphreys 5 Argyle Square REID ACT 2612 The application was signed by the secretary of the party and accompanied by a copy of the party’s constitution, and otherwise complied with section 89 of the Electoral Act. Notification of the application to register the party was published in the Gazette and the Canberra Times on 27 July 2001. The notice stated that objections to the registration of the party could be made up to 10 August 2001. Objections to the application Two objections to the party’s application for registration were received before the closing date. Mr John Ryan, General Secretary, The Liberal Party of Australia, ACT Division, objected in writing on 7 August 2001 to the registration of the party on the ground set out in section 93(2)(d) of the Electoral Act, that is, that the name of party so nearly resembles the name of another registered party that it is likely to be confused with or mistaken for that name. In support of this objection Mr Ryan gives an example of the recent Western Australian State election where election campaign workers for the “liberals for forests” party were advising that “there are two Liberal Party candidates standing for this electorate”. -

HON. GIZ WATSON B. 1957

PARLIAMENTARY HISTORY ADVISORY COMMITTEE AND STATE LIBRARY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA TRANSCRIPT OF AN INTERVIEW WITH HON. GIZ WATSON b. 1957 - STATE LIBRARY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA - ORAL HISTORY COLLECTION DATE OF INTERVIEW: 2015-2016 INTERVIEWER: ANNE YARDLEY TRANSCRIBER: ANNE YARDLEY DURATION: 19 HOURS REFERENCE NUMBER: OH4275 COPYRIGHT: PARLIAMENT OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA & STATE LIBRARY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA. GIZ WATSON INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPTS NOTE TO READER Readers of this oral history memoir should bear in mind that it is a verbatim transcript of the spoken word and reflects the informal, conversational style that is inherent in such historical sources. The Parliament and the State Library are not responsible for the factual accuracy of the memoir, nor for the views expressed therein; these are for the reader to judge. Bold type face indicates a difference between transcript and recording, as a result of corrections made to the transcript only, usually at the request of the person interviewed. FULL CAPITALS in the text indicate a word or words emphasised by the person interviewed. Square brackets [ ] are used for insertions not in the original tape. ii GIZ WATSON INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPTS CONTENTS Contents Pages Introduction 1 Interview - 1 4 - 22 Parents, family life and childhood; migrating from England; school and university studies – Penrhos/ Murdoch University; religion – Quakerism, Buddhism; countryside holidays and early appreciation of Australian environment; Anti-Vietnam marches; civil-rights movements; Activism; civil disobedience; sport; studying environmental science; Albany; studying for a trade. Interview - 2 23 - 38 Environmental issues; Campaign to Save Native Forests; non-violent Direct Action; Quakerism; Alcoa; community support and debate; Cockburn Cement; State Agreement Acts; campaign results; legitimacy of activism; “eco- warriors”; Inaugural speech . -

Green Parties and Elections to the European Parliament, 1979–2019 Green Par Elections

Chapter 1 Green Parties and Elections, 1979–2019 Green parties and elections to the European Parliament, 1979–2019 Wolfgang Rüdig Introduction The history of green parties in Europe is closely intertwined with the history of elections to the European Parliament. When the first direct elections to the European Parliament took place in June 1979, the development of green parties in Europe was still in its infancy. Only in Belgium and the UK had green parties been formed that took part in these elections; but ecological lists, which were the pre- decessors of green parties, competed in other countries. Despite not winning representation, the German Greens were particularly influ- enced by the 1979 European elections. Five years later, most partic- ipating countries had seen the formation of national green parties, and the first Green MEPs from Belgium and Germany were elected. Green parties have been represented continuously in the European Parliament since 1984. Subsequent years saw Greens from many other countries joining their Belgian and German colleagues in the Euro- pean Parliament. European elections continued to be important for party formation in new EU member countries. In the 1980s it was the South European countries (Greece, Portugal and Spain), following 4 GREENS FOR A BETTER EUROPE their successful transition to democracies, that became members. Green parties did not have a strong role in their national party systems, and European elections became an important focus for party develop- ment. In the 1990s it was the turn of Austria, Finland and Sweden to join; green parties were already well established in all three nations and provided ongoing support for Greens in the European Parliament. -

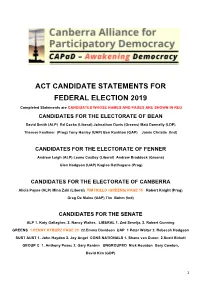

File of Candidate Statements 1

ACTwww.canberra CANDIDATE STATEMENTS-alliance.org.au FOR FEDERAL ELECTION 2019 Completed Statements are CANDIDATES WHOSE NAMES AND PAGES ARE SHOWN IN RED Responses to CANDIDATES FOR THE ELECTORATE OF BEAN [email protected] David Smith (ALP) Ed Cocks (Liberal) Johnathan Davis (Greens) Matt Donnelly (LDP) Enquiries to Bob Douglas Therese Faulkner (Prog) Tony Hanley (UAP) Ben Rushton (GAP) Jamie Christie (Ind)Tel 02 6253 4409 or 0409 233138 CANDIDATES FOR THE ELECTORATE OF FENNER Dear Dr Christie, Andrew Leigh (ALP) Leane Castley (Liberal) Andrew Braddock (Greens) Glen Hodgson (UAP) Kagiso Ratlhagane (Prog) I understand you are a candidate for the forthcoming Federal Election. CANDIDATES FOR THE ELECTORATE OF CANBERRA Congratulations, and best wishes.Alicia Payne (ALP) Mina Zaki (Liberal) TIM HOLLO (GREENS) PAGE 15 Robert Knight (Prog) Greg De Maine (UAP) Tim Bohm (Ind) I am writing on behalf of The Canberra Alliance for Participatory Democracy (CAPaD), which was formed in 2014, because many CanberransCANDIDATES were FORconcerned THE SENATE at the directions that Australian democracy was taking. ALP 1. Katy Gallagher, 2. Nancy Waites. LIBERAL 1. Zed Seselja, 2. Robert Gunning GREENS 1.PENNY KYBURZ PAGE 23 22.Emma Davidson UAP 1 Peter Walter 2. Rebecah Hodgson CAPaD seeks to enhanceSUST democracy AUST 1. John Haydon 2. Joyin Angel Canberra, CONS NATIONALS 1. Shaneso van Durenthat 2.Scott citizensBirkett can trust their elected GEOUP C 1. Anthony Pesec 2. Gary Kentnn UNGROUPED Nick Houston Gary Cowton, representatives, hold them accountable, engageDavid Kim in (GDP) decision -making, and defend what sustains the public interest. In the lead up to the 2016 ACT Legislative Assembly Elections, the major1 parties were consulted for their views about individual candidate statements, and in the light of those responses, a candidate statement was prepared, which we offered to all registered candidates for lodgement on the CAPaD website. -

Influence on the U.S. Environmental Movement

Australian Journal of Politics and History: Volume 61, Number 3, 2015, pp.414-431. Exemplars and Influences: Transnational Flows in the Environmental Movement CHRISTOPHER ROOTES Centre for the Study of Social and Political Movements, School of Social Policy, Sociology and Social Research, University of Kent, Canterbury, UK Transnational flows of ideas are examined through consideration of Green parties, Friends of the Earth, and Earth First!, which represent, respectively, the highly institutionalised, the semi- institutionalised and the resolutely non-institutionalised dimensions of environmental activism. The focus is upon English-speaking countries: US, UK and Australia. Particular attention is paid to Australian cases, both as transmitters and recipients of examples. The influence of Australian examples on Europeans has been overstated in the case of Green parties, was negligible in the case of Friends of the Earth, but surprisingly considerable in the case of Earth First!. Non-violent direct action in Australian rainforests influenced Earth First! in both the US and UK. In each case, the flow of influence was mediated by individuals, and outcomes were shaped by the contexts of the recipients. Introduction Ideas travel. But they do not always travel in straight lines. The people who are their bearers are rarely single-minded; rather, they carry and sometimes transmit all sorts of other ideas that are in varying ways and to varying degrees discrepant one with another. Because the people who carry and transmit them are in different ways connected to various, sometimes overlapping, sometimes discrete social networks, ideas are not only transmitted in variants of their pure, original form, but they become, in these diverse transmuted forms, instantiated in social practices that are embedded in differing institutional contexts. -

Professionalization of Green Parties?

Professionalization of Green parties? Analyzing and explaining changes in the external political approach of the Dutch political party GroenLinks Lotte Melenhorst (0712019) Supervisor: Dr. A. S. Zaslove 5 September 2012 Abstract There is a relatively small body of research regarding the ideological and organizational changes of Green parties. What has been lacking so far is an analysis of the way Green parties present them- selves to the outside world, which is especially interesting because it can be expected to strongly influence the image of these parties. The project shows that the Dutch Green party ‘GroenLinks’ has become more professional regarding their ‘external political approach’ – regarding ideological, or- ganizational as well as strategic presentation – during their 20 years of existence. This research pro- ject challenges the core idea of the so-called ‘threshold-approach’, that major organizational changes appear when a party is getting into government. What turns out to be at least as interesting is the ‘anticipatory’ adaptations parties go through once they have formulated government participation as an important party goal. Until now, scholars have felt that Green parties are transforming, but they have not been able to point at the core of the changes that have taken place. Organizational and ideological changes have been investigated separately, whereas in the case of Green parties organi- zation and ideology are closely interrelated. In this thesis it is argued that the external political ap- proach of GroenLinks, which used to be a typical New Left Green party but that lacks governmental experience, has become more professional, due to initiatives of various within-party actors who of- ten responded to developments outside the party. -

Ambassade De France En Australie – Service De Presse Et Information Site : Tél

Online Press review 7 May 2015 The articles in purple are not available online. Please contact the Press and Information Department. FRONT PAGE New Greens leaders seek ‘common ground’ on reform (AUS) Crowe The Greens are promising a fresh look at major budget savings after the sudden installation of Richard Di Natale as the party’s new leader signalled a dramatic shift in power to a new generation but stirred internal rancour. Get over historical indigenous wrongs: Noel Pearson (AUS) Bita Aboriginal leader Noel Pearson has challenged indigenous Australians to get over their traumatic history in the same way that Jews survived the Holocaust. Federal budget 2015: GST on Netflix and more on the way (CAN+SMH) Martin The federal government will move to impose the goods and services tax on services such as Netflix under new rules set to be included in next week's budget. Federal budget 2015: Census saved, $250m investment in Bureau of Statistics (CAN) Martin The census has been saved and the Australian Bureau of Statistics will get a $250 million funding boost as part of the biggest technology upgrade in its 110-year history. DOMESTIC AFFAIRS POLITICS Abbott rejects slur on Paris meeting as Fairfax Media slammed (AUS) Owens Tony Abbott has denied knowing that ambassador Stephen Brady’s male partner had been instructed to leave the tarmac of a Paris airport before the Prime Minister’s arrival on Anzac Day. Smearing Tony Abbott as a homophobe is victory for hatred (AUS/Comment) Kenny Given Tony Abbott has been dubbed a misogynist, Islamophobe and racist, I suppose the - occasional allegation of homophobia shouldn’t be a surprise. -

Nutrient Requirements of Poultry and Nutritional Research

BOOK REVIEWS RECENSIONS DE LIVRES Control and Manipulation of The remaining bulk of the sium held in Edinburgh in 1984. Animal Growth. P.J. Buttery. chapters deal with hormonal control Readers familiar with this very suc- N.B. Haynes and D.B. Lindsay. of growth, with specific sections on cesful series are again presented Published by Butterworths, growth hormone, prostaglandins, with a change in format, and after London. 1986. 347 pages. Price insulin, glucocorticoids, 1-adrenergic the 1985 volume appears, future $125.00. agonists, and various hormone- plans are for only biennial meetings releasing factors. These chapters are and proceedings. This book is the proceedings of the somewhat diverse in approach, The opening and final chapters of long-established and successful some dealing with only biochemical the proceedings deal with nutrition yearly Easter School in Agricultural parameters, and others describing research past and future, and are of Science, from the University of animal function and performance. such a general nature as to seem out Nottingham, England. Over half of In general the reader is given a good of place in relation to the other the 20 chapters are concerned with overview, and current literature is technical papers. The remaining the relationship of endogenous and cited for further reading. In terms chapters seem to be arranged in no exogenous hormones and growth, of endogenous hormone manipula- particular order and the reader is and it is somewhat unfortunate that tion, the reader is provided with continually transferred back and the title does not reflect this topical some thoughts of future direction in forth from theoretical aspects of theme. -

Take Heart and Name WA's New Federal Seat Vallentine 2015 Marks 30 Years Since Jo Vallentine Took up Her Senate Position

Take heart and name WA’s new federal seat Vallentine 2015 marks 30 years since Jo Vallentine took up her senate position, the first person in the world to be elected on an anti-nuclear platform. What better way to acknowledge her contribution to peace, nonviolence and protecting the planet than to name a new federal seat after her? The official Australian parliament website describes Jo Vallentine in this way: Jo Vallentine was elected in 1984 to represent Western Australia in the Senate for the Nuclear Disarmament Party, running with the slogan ‘Take Heart—Vote Vallentine’. She commenced her term in July 1985 as an Independent Senator for Nuclear Disarmament, claiming in her first speech that she was the first member of any parliament in the world to be elected on this platform. When she stood for election again in 1990, she was elected as a senator for The Greens (Western Australia), and was the first Green in the Australian Senate. … During her seven years in Parliament, Vallentine was a persistent voice for peace, nuclear disarmament, Aboriginal land rights, social justice and the environment (emphasis added)i. Jo Vallentine’s parliamentary and subsequent career should be recognised in the named seat of Vallentine because: 1. Jo Vallentine was the first woman or person in several roles, in particular: The first person in the world to win a seat based on a platform of nuclear disarmament The first person to be elected to federal parliament as a Greens party politician. The Greens are now Australia’s third largest political party, yet no seat has been named after any of their political representatives 2. -

Australian Electoral Commission Seventh

AUSTRALIAN ELECTORAL COMMISSION SEVENTH SUBMISSION TO THE JOINT STANDING COMMITTEE ON ELECTORAL MATTERS' INQUIRY INTO THE 2004 FEDERAL ELECTION AND MATTERS RELATED THERETO Responses to issues raised by JSCEM at Perth and Sydney public hearings and additional requests for information from the JSCEM 9 September 2005 SEVENTH SUBMISSION TO THE JSCEM 2004 FEDERAL ELECTION INQUIRY Introduction This is the seventh submission by the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) to the Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters' (JSCEM) inquiry into the conduct of the 2004 federal election. This submission provides responses to requests for information, documentation and statistics that were either taken on notice or requested of AEC staff during the Perth and Sydney hearings of the current inquiry, or as subsequent requests through the JSCEM secretariat. The submission also provides some additional information in relation to issues raised in public hearings. The table of contents (below) sets out the relevant issues raised, identified by subject matter and, where relevant, the page number of the relevant Hansard transcript. Correction On page 10 of the AEC’s sixth submission, in the fourth paragraph, there is a typographical error. The sentence that begins ‘The AEC notes that the AEC Electoral Commission …’ should read ‘The AEC notes that the ACT Electoral Commission…’ Contents 1. PERTH HEARING – WEDNESDAY 3 AUGUST ________________________ 4 Page 57: HTV cards 2001 _________________________________________________ 4 Page 58: Dual polling places _______________________________________________ -

Senator Bob Brown - Australian Greens

Senator Bob Brown - Australian Greens Bob Brown, born in 1944, was educated in rural New South Wales, became captain of Blacktown Boys High School in Sydney and graduated in medicine from Sydney University in 1968. He became the Director of the Wilderness Society which organised the blockade of the dam-works on Tasmania’s wild Franklin River in 1982/3. Some 1500 people were arrested and 600 jailed, including Bob Brown who spent 19 days in Risdon Prison. On the day of his release, he was elected as the first Green into Tasmania's Parliament. After federal government intervention, the Franklin River was protected in 1983. As a State MP, Bob Brown introduced a wide range of private member's initiatives, including for freedom of information, death with dignity, lowering parliamentary salaries, gay law reform, banning the battery-hen industry and nuclear free Tasmania. Some succeeded, others not. Regrettably, his 1987 bill to ban semi-automatic guns was voted down by both Liberal and Labor members of the House of Assembly, seven years before the Port Arthur massacre. In 1989, he led the parliamentary team of five Greens which held the balance of power with the Field Labor Government. The Greens saved 25 schools from closure, instigated the Local Employment Initiatives which created more than 1000 jobs in depressed areas, doubled the size of Tasmania's Wilderness World Heritage Area to 1.4 million hectares, created the Douglas-Apsley National Park and supported tough fiscal measures to recover from the debts of the previous Liberal regime. Bob resigned from the State Parliament in 1993 and Christine Milne took over as leader of the Tasmanian Greens. -

The Charter and Constitution of the Australian Greens May 2020 Charter

The Charter and Constitution of the Australian Greens May 2020 Charter .......................................................................................................................................................................3 Basis of The Charter ..............................................................................................................................................3 Ecology ..................................................................................................................................................................3 Democracy.............................................................................................................................................................3 Social Justice .........................................................................................................................................................3 Peace ....................................................................................................................................................................3 An Ecologically Sustainable Economy ....................................................................................................................4 Meaningful Work ....................................................................................................................................................4 Culture ...................................................................................................................................................................4