The Dutch Parliamentary Elections: Outcome and Implications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

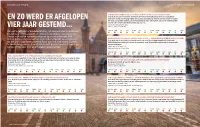

En Zo Werd Er De Afgelopen Vier Jaar Gestemd

UITKERINGSGERECHTIGDEN TWEEDE KAMER VERKIEZINGEN EEN INKOMENSAANVULLING VOOR MENSEN MET EEN MEDISCHE URENBEPERKING Deze motie beoogde te bereiken dat mensen met een beperking/handicap die naar hun maximale EN ZO WERD ER AFGELOPEN vermogen werken, een toeslag krijgen die los staat van eventueel inkomen van een partner of ouders. Dit omdat zij vanwege die medische urenbeperking dus maar een beperkt aantal uren kunnen werken en zodoende onvoldoende inkomen kunnen genereren. Stemdatum: 24 september 2019 VIER JAAR GESTEMD… Indiener: Jasper van Dijk (SP) Van extra geld voor armoedebestrijding, tot aanpassingen in de Wajong. 50PLUS CDA CU D66 DENK FvD GL PvdA PvdD PVV SGP SP VVD De afgelopen vier jaar heeft de Tweede Kamer kunnen stemmen over diverse voorstellen ter verbetering van de sociale zekerheid. FNV Uitkeringsgerechtigden heeft er acht moties uitgepikt. Groen betekent AANPASSEN WETSVOORSTEL WAJONG OM DE REGELS TE HARMONISEREN ZONDER VERSLECHTERING Deze motie was bedoeld om het alternatief zoals opgesteld door belangenorganisaties (onder wie dat een partij voor heeft gestemd. Rood was een stem tegen. Duidelijk FNV Uitkeringsgerechtigden) in de wet te verwerken, zodat de nadelige gevolgen van de harmonisatie te zien is dat geen van de moties het heeft gehaald omdat de regerings- worden voorkomen. partijen (VVD, CDA, D66 en CU) steeds tegenstemden. Stemdatum: 30 oktober 2019 Indieners: PvdA, GL, SP en 50Plus 50PLUS CDA CU D66 DENK FvD GL PvdA PvdD PVV SGP SP VVD EEN AANGESCHERPT AFSLUITINGSBELEID VOOR DRINKWATER EN WIFI Deze motie was opgesteld om naast gas en elektriciteit ook drinkwater en internet op te nemen als basis- voorziening. Dit om te voorkomen dat mensen met een betalingsachterstand in een onleefbare situatie EXTRA GELD OM DE GEVOLGEN VAN ARMOEDE ONDER KINDEREN TE BESTRIJDEN belanden als deze voorzieningen worden afgesloten. -

I&O-Zetelpeiling 15 Maart 2021

Rapport I&O-Zetelpeiling 15 maart 2021 VVD levert verder in; D66 stijgt door; Volt en Ja21 maken goede kans Colofon Maart peiling #2 I&O Research Uitgave I&O Research Piet Heinkade 55 1019 GM Amsterdam Rapportnummer 2021/69 Datum maart 2021 Auteurs Peter Kanne Milan Driessen Het overnemen uit deze publicatie is toegestaan, mits de bron (I&O Research) duidelijk wordt vermeld. 15 maart 2021 2 van 15 Inhoudsopgave Belangrijkste uitkomsten _____________________________________________________________________ 4 1 I&O-zetelpeiling: VVD levert verder in ________________________________________________ 7 VVD levert verder in, D66 stijgt door _______________________ 7 Wie verliest aan wie en waarom? _________________________ 9 Aandeel zwevende kiezers _____________________________ 11 Partij van tweede (of derde) voorkeur_______________________ 12 Stemgedrag 2021 vs. stemgedrag 2017 ______________________ 13 2 Onderzoeksverantwoording _________________________________________________________ 14 15 maart 2021 3 van 15 Belangrijkste uitkomsten VVD levert verder in; D66 stijgt door; Volt en Ja21 maken goede kans In de meest recente I&O-zetelpeiling – die liep van vrijdag 12 tot maandagochtend 15 maart – zien we de VVD verder inleveren (van 36 naar 33 zetels) en D66 verder stijgen (van 16 naar 19 zetels). Bij peilingen (steekproefonderzoek) moet rekening gehouden worden met onnauwkeurigheids- marges. Voor VVD (21,0%, marge 1,6%) en D66 (11,8%, marge 1,3%) zijn dat (ruim) 2 zetels. De verschuiving voor D66 is statistisch significant, die voor VVD en PvdA zijn dat nipt. Als we naar deze zetelpeiling kijken – 2 dagen voor de verkiezingen – valt op hoezeer hij lijkt op de uitslag van de Tweede Kamerverkiezingen van 2017. Van de winst die de VVD boekte in de coronacrisis is niets over: nu 33 zetels, vier jaar geleden ook 33 zetels. -

KEY QUESTIONS the Big Six

The Netherlands Donor Profile KEY QUESTIONS the big six Who are the main actors in the Netherlands' development cooperation? Minister for Foreign Trade and Development Coop- advocating for shorter public versions of these strategies eration leads on strategy; embassies administer bi- to be openly available, when finalized. lateral ODA The role of Parliament is to scrutinize development poli- Prime Minister Mark Rutte (People’s Party for Freedom cy and budget allocations. Parliament can annually and Democracy, VVD), currently in his third term of of- amend the government’s draft budget bill. Parliamenta- fice, has led a coalition government with the social-liber- ry debates in November/December can lead to significant al Democrats 66 (D66), the Christian Democratic Appeal changes to the ODA budget. (CDA), and the Christian Union (CU) since 2017. The Min- istry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) defines priorities for Dutch Dutch civil society organizations (CSOs) play an active development policy, currently under the leadership of role in Dutch development cooperation. The develop- Stef Blok (VVD). Minister for Foreign Trade and Develop- ment CSO umbrella association, Partos, represents over ment Cooperation (MFTDC) Sigrid Kaag (D66) leads the 100 organizations. They engage with the Parliament and MFA’s work on development cooperation. Within the the MFA to influence policy and funding decisions. Many MFA, the Directorate-General for International Coopera- CSOs implement their own programs in developing coun- tion (DGIS) is responsible for designing and coordinating tries and are funded by the Dutch government and the implementation of development policy. through private donations. In 2015, program funding for CSOs was sharply cut, and since then, a larger focus has Unlike many other donors, the Netherlands does not been placed on strategic partnerships and advocacy. -

Voter Turnout in Texas: Can It Be Higher?

Voter Turnout in Texas: Can It Be Higher? JAMES MCKENZIE Texas Lyceum Fellow WHAT’S THE TAKEAWAY? In the 2016 presidential election, Texas’ voter turnout Texas’ voter turnout is among placed near the bottom of all the states, ranking 47th. In the lowest in the nation. Texas’ recent 2018 mid-term election, which featured a Low turnout can lead to policies closely contested US Senate race and concurrent favoring the interests of gubernatorial election, not even half of eligible voters demographic groups whose (46.3%) participated.1 members are more likely to vote. Low voter turnout is not a recent phenomenon in Texas. Tex- There are deterrents to as has consistently lagged the national average in presidential registering and voting that the elections for voter turnout among the voting eligible popula- state can address. tion (VEP). In fact, since 2000, the gap between Texas’ turn- out and the national average consecutively widened in all but Policies such as same-day registration, automatic voter one election cycle.2 Texans may be open to changes to address registration, mail-in early voting, low turnout. According to a 2019 poll by the Texas Lyceum on and Election Day voting centers Texans’ attitudes toward democracy, a majority (61%) agreed could help. that “significant changes” are needed to make our electoral system work for current times.3 VOLUME 10 | ISSUE 6 | SEPTEMBER 2019 2 DOES VOTER TURNOUT MATTER? This report addresses ways to boost voter Voter turnout is often considered the curren- participation in both population sets. cy of democracy, a way for citizen’s prefer- ences to be expressed. -

INVITATION Award Ceremony for Maneka Gandhi: Award Ceremony for Richard Ryder: in Part 2 Only Starting at 9:00 A.M

Peter-Singer-Preis 2021 The award ceremony is carried out as a closed event and is open to altogether 120 guests only Förderverein des Association for the Peter-Singer-Preises Promotion of the Peter für Strategien zur Singer Prize for AWARD CEREMONY MEMBERSHIP Tierleidminderung e.V. Strategies to Reduce the Suffering of Animals Award Ceremony for Maneka Gandhi as the Winner of the 6th and Richard Ryder as the I would like to become a member of the Association for the Promo- tion of the Peter Singer Prize for Strategies to Reduce the Suffe- th ring of Animals. Winner of the 7 Peter Singer Prize for Strategies to Reduce the Suffering of Animals. Registered non-profit association www.peter-singer-preis.de • E-Mail: [email protected] th My membership fee is Euro every year DATE: Saturday, May 29 , 2021 (minimal fee is 50 Euro every year for one person) VENUE: Hollywood Media Hotel (Cinema Hall) • Kurfürstendamm 202 • 10719 Berlin PARTICIPATION I would like to participate in the whole evemt. PROGRAMME: FIRST PART PROGRAMME: SECOND PART in part 1 only INVITATION Award Ceremony for Maneka Gandhi: Award Ceremony for Richard Ryder: in part 2 only Starting at 9:00 A.M. Starting at 4:00 P.M. Name: • Welcome: Dr. Walter Neussel • Moderation: Prof. Edna Hillmann Street, house number: • Moderation: Prof. Dr. Peter Singer (Professor for Animal Husbandry, Humboldt University, Berlin) • Prof. Dr. Ernst Ulrich von Weizsäcker Postcode, city: (Honorary President of the Club of Rome): • Prof. Dr. Dr. h.c. Dieter Birnbacher Telephone, fax: Avoiding Collapse of the “Full World” (Institute of Philosophy, Heinrich Heine University, Düsseldorf): • Renate Künast Email adress: (Former German Minister of Consumer Protection, „Speciesism“– a Re-Evaluation Place, date, signature: Food and Agriculture from 2001 to 2005): • Prof. -

Meat and Morality: Alternatives to Factory Farming

J Agric Environ Ethics (2010) 23:455–468 DOI 10.1007/s10806-009-9226-x Meat and Morality: Alternatives to Factory Farming Evelyn B. Pluhar Accepted: 30 November 2009 / Published online: 18 December 2009 Ó Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2009 Abstract Scientists have shown that the practice of factory farming is an increasingly urgent danger to human health, the environment, and nonhuman animal welfare. For all these reasons, moral agents must consider alternatives. Vegetarian food production, humane food animal farming, and in-vitro meat production are all explored from a variety of ethical perspectives, especially utilitarian and rights- based viewpoints, all in the light of current U.S. and European initiatives in the public and private sectors. It is concluded that vegetarianism and potentially in-vitro meat production are the best-justified options. Keywords Factory farming Á Humane farming Á In-vitro meat production Á Rights theory Á Utilitarianism Á Vegetarianism factory farming (FAK-tuh-ree FAHR-ming) noun: an industrialized system of producing meat, eggs, and milk in large-scale facilities where the animal is treated as a machine (Wordsmith 2008) After several years of receiving ‘‘A Word for the Day’’ from a dictionary service, the author was interested to see the above definition pop up in the email inbox. The timing was perhaps not coincidental. In spring 2008, the Pew Commission on Industrial Farm Animal Production completed a two-year investigation of factory- farming practices in the United States. At the end of its 1,100-page report, the Commission recommended a ten-year timeline for the termination of the most intensive production techniques, including battery cages, gestation crates, and force- feeding birds to harvest their fatty livers for foie gras (Hunger Notes 2008). -

THE CASE AGAINST Marine Mammals in Captivity Authors: Naomi A

s l a m m a y t T i M S N v I i A e G t A n i p E S r a A C a C E H n T M i THE CASE AGAINST Marine Mammals in Captivity The Humane Society of the United State s/ World Society for the Protection of Animals 2009 1 1 1 2 0 A M , n o t s o g B r o . 1 a 0 s 2 u - e a t i p s u S w , t e e r t S h t u o S 9 8 THE CASE AGAINST Marine Mammals in Captivity Authors: Naomi A. Rose, E.C.M. Parsons, and Richard Farinato, 4th edition Editors: Naomi A. Rose and Debra Firmani, 4th edition ©2009 The Humane Society of the United States and the World Society for the Protection of Animals. All rights reserved. ©2008 The HSUS. All rights reserved. Printed on recycled paper, acid free and elemental chlorine free, with soy-based ink. Cover: ©iStockphoto.com/Ying Ying Wong Overview n the debate over marine mammals in captivity, the of the natural environment. The truth is that marine mammals have evolved physically and behaviorally to survive these rigors. public display industry maintains that marine mammal For example, nearly every kind of marine mammal, from sea lion Iexhibits serve a valuable conservation function, people to dolphin, travels large distances daily in a search for food. In learn important information from seeing live animals, and captivity, natural feeding and foraging patterns are completely lost. -

JA21 VERKIEZINGSPROGRAMMA 2021-2025 Het Juiste Antwoord VOORWOORD

JA21 VERKIEZINGSPROGRAMMA 2021-2025 Het Juiste Antwoord VOORWOORD Net als velen van u zou ik nergens liever willen leven dan hier. Ons mooie land heeft een gigantisch potentieel. We zijn innovatief, nuchter, hardwer- kend, trots op wie we zijn en gezegend met een indrukwekkende geschie- denis en een gezonde handelsgeest. Een Nederland dat Nederland durft te zijn is tot ongekende prestaties in staat. Al sinds de komst van Pim Fortuyn in 2002 laten miljoenen kiezers weten dat het op de grote terreinen van misdaad, migratie, het functioneren van de publieke sector en Europa anders moet. Nederland zal in een uitdijend en oncontroleerbaar Europa meer voor zichzelf moeten kiezen en vertrouwen en macht moeten terugleggen bij de kiezer. Maar keer op keer krijgen rechtse kiezers geen waar voor hun stem. Wie rechts stemt krijgt daar immigratierecords, een steeds verder uitdijende overheid, stijgende lasten, een verstikkend ondernemersklimaat, afschaffing van het referendum en een onbetaalbaar en irrationeel klimaatbeleid voor terug die ten koste gaan van onze welvaart en ons woongenot. Ons programma is een realistische conservatief-liberale koers voor ieder- een die de schouders onder Nederland wil zetten. Positieve keuzes voor een welvarender, veiliger en herkenbaarder land waarin we criminaliteit keihard aanpakken, behouden wat ons bindt en macht terughalen uit Europa. Met een overheid die er voor de burgers is en goed weet wat ze wel, maar ook juist niet moet doen. Een land waarin we hart hebben voor wie niet kan, maar hard zullen zijn voor wie niet wil. Wij zijn er klaar voor. Samen met onze geweldige fracties in de Eerste Kamer, het Europees Parlement en de Amsterdamse gemeenteraad én met onze vertegenwoordigers in de Provinciale Staten zullen wij na 17 maart met grote trots ook uw stem in de Tweede Kamer gaan vertegenwoordigen. -

Randomocracy

Randomocracy A Citizen’s Guide to Electoral Reform in British Columbia Why the B.C. Citizens Assembly recommends the single transferable-vote system Jack MacDonald An Ipsos-Reid poll taken in February 2005 revealed that half of British Columbians had never heard of the upcoming referendum on electoral reform to take place on May 17, 2005, in conjunction with the provincial election. Randomocracy Of the half who had heard of it—and the even smaller percentage who said they had a good understanding of the B.C. Citizens Assembly’s recommendation to change to a single transferable-vote system (STV)—more than 66% said they intend to vote yes to STV. Randomocracy describes the process and explains the thinking that led to the Citizens Assembly’s recommendation that the voting system in British Columbia should be changed from first-past-the-post to a single transferable-vote system. Jack MacDonald was one of the 161 members of the B.C. Citizens Assembly on Electoral Reform. ISBN 0-9737829-0-0 NON-FICTION $8 CAN FCG Publications www.bcelectoralreform.ca RANDOMOCRACY A Citizen’s Guide to Electoral Reform in British Columbia Jack MacDonald FCG Publications Victoria, British Columbia, Canada Copyright © 2005 by Jack MacDonald All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by an information storage and retrieval system, now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher. First published in 2005 by FCG Publications FCG Publications 2010 Runnymede Ave Victoria, British Columbia Canada V8S 2V6 E-mail: [email protected] Includes bibliographical references. -

Factsheet: the Dutch House of Representatives Tweede Kamer 1

Directorate-General for the Presidency Directorate for Relations with National Parliaments Factsheet: The Dutch House of Representatives Tweede Kamer 1. At a glance The Netherlands is the main constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, with its monarch King Willem-Alexander. Since 1848 it has been governed as a parliamentary democracy and a constitutional monarchy, organised as a unitary state. The Dutch Parliament "Staten-Generaal" is a bicameral body. It consists of two chambers, both of which are elected for four-year terms. The Senate, the Eerste Kamer is indirectly elected. It consists of 75 members and is elected by the (directly elected) members of the 12 provincial state councils, known as the "staten". The 150 members of the House of Representatives, the Tweede Kamer, are directly elected through a national party-list system, on the basis of proportional representation. On 26 October 2017 the third Cabinet of Prime Minister Mark Rutte took office. Four political parties formed the governing coalition: People's Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD), Christian Democratic Appeal (CDA), Democrats 66 (D66) and Christian Union (CU). On 15 January 2021 the government resigned over the child benefits affair. The government will stay on in caretaker capacity until general elections scheduled for 17 March 2021. 2. Composition Results of the parliamentary elections of 15 March 2017 and current redistribution of seats Party EP % Seats affiliation Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie (VVD) 321 People's Party for Freedom and Democracy 21,3% (33) Partij Voor de Vrijheid (PVV) Party for Freedom 13,1% 20 Christen Democratisch Appèl (CDA) Christian Democratic Appeal 12,4% 19 Democraten 66 (D66) Democrats 66 12,2% 19 1 In 2019, Wybren van Haga, was expelled from the VVD. -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Professionalization of Green Parties?

Professionalization of Green parties? Analyzing and explaining changes in the external political approach of the Dutch political party GroenLinks Lotte Melenhorst (0712019) Supervisor: Dr. A. S. Zaslove 5 September 2012 Abstract There is a relatively small body of research regarding the ideological and organizational changes of Green parties. What has been lacking so far is an analysis of the way Green parties present them- selves to the outside world, which is especially interesting because it can be expected to strongly influence the image of these parties. The project shows that the Dutch Green party ‘GroenLinks’ has become more professional regarding their ‘external political approach’ – regarding ideological, or- ganizational as well as strategic presentation – during their 20 years of existence. This research pro- ject challenges the core idea of the so-called ‘threshold-approach’, that major organizational changes appear when a party is getting into government. What turns out to be at least as interesting is the ‘anticipatory’ adaptations parties go through once they have formulated government participation as an important party goal. Until now, scholars have felt that Green parties are transforming, but they have not been able to point at the core of the changes that have taken place. Organizational and ideological changes have been investigated separately, whereas in the case of Green parties organi- zation and ideology are closely interrelated. In this thesis it is argued that the external political ap- proach of GroenLinks, which used to be a typical New Left Green party but that lacks governmental experience, has become more professional, due to initiatives of various within-party actors who of- ten responded to developments outside the party.