Ethnic Outbidding and the Emergence of DENK in the Netherlands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

En Zo Werd Er De Afgelopen Vier Jaar Gestemd

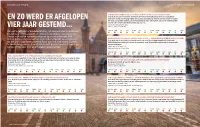

UITKERINGSGERECHTIGDEN TWEEDE KAMER VERKIEZINGEN EEN INKOMENSAANVULLING VOOR MENSEN MET EEN MEDISCHE URENBEPERKING Deze motie beoogde te bereiken dat mensen met een beperking/handicap die naar hun maximale EN ZO WERD ER AFGELOPEN vermogen werken, een toeslag krijgen die los staat van eventueel inkomen van een partner of ouders. Dit omdat zij vanwege die medische urenbeperking dus maar een beperkt aantal uren kunnen werken en zodoende onvoldoende inkomen kunnen genereren. Stemdatum: 24 september 2019 VIER JAAR GESTEMD… Indiener: Jasper van Dijk (SP) Van extra geld voor armoedebestrijding, tot aanpassingen in de Wajong. 50PLUS CDA CU D66 DENK FvD GL PvdA PvdD PVV SGP SP VVD De afgelopen vier jaar heeft de Tweede Kamer kunnen stemmen over diverse voorstellen ter verbetering van de sociale zekerheid. FNV Uitkeringsgerechtigden heeft er acht moties uitgepikt. Groen betekent AANPASSEN WETSVOORSTEL WAJONG OM DE REGELS TE HARMONISEREN ZONDER VERSLECHTERING Deze motie was bedoeld om het alternatief zoals opgesteld door belangenorganisaties (onder wie dat een partij voor heeft gestemd. Rood was een stem tegen. Duidelijk FNV Uitkeringsgerechtigden) in de wet te verwerken, zodat de nadelige gevolgen van de harmonisatie te zien is dat geen van de moties het heeft gehaald omdat de regerings- worden voorkomen. partijen (VVD, CDA, D66 en CU) steeds tegenstemden. Stemdatum: 30 oktober 2019 Indieners: PvdA, GL, SP en 50Plus 50PLUS CDA CU D66 DENK FvD GL PvdA PvdD PVV SGP SP VVD EEN AANGESCHERPT AFSLUITINGSBELEID VOOR DRINKWATER EN WIFI Deze motie was opgesteld om naast gas en elektriciteit ook drinkwater en internet op te nemen als basis- voorziening. Dit om te voorkomen dat mensen met een betalingsachterstand in een onleefbare situatie EXTRA GELD OM DE GEVOLGEN VAN ARMOEDE ONDER KINDEREN TE BESTRIJDEN belanden als deze voorzieningen worden afgesloten. -

I&O-Zetelpeiling 15 Maart 2021

Rapport I&O-Zetelpeiling 15 maart 2021 VVD levert verder in; D66 stijgt door; Volt en Ja21 maken goede kans Colofon Maart peiling #2 I&O Research Uitgave I&O Research Piet Heinkade 55 1019 GM Amsterdam Rapportnummer 2021/69 Datum maart 2021 Auteurs Peter Kanne Milan Driessen Het overnemen uit deze publicatie is toegestaan, mits de bron (I&O Research) duidelijk wordt vermeld. 15 maart 2021 2 van 15 Inhoudsopgave Belangrijkste uitkomsten _____________________________________________________________________ 4 1 I&O-zetelpeiling: VVD levert verder in ________________________________________________ 7 VVD levert verder in, D66 stijgt door _______________________ 7 Wie verliest aan wie en waarom? _________________________ 9 Aandeel zwevende kiezers _____________________________ 11 Partij van tweede (of derde) voorkeur_______________________ 12 Stemgedrag 2021 vs. stemgedrag 2017 ______________________ 13 2 Onderzoeksverantwoording _________________________________________________________ 14 15 maart 2021 3 van 15 Belangrijkste uitkomsten VVD levert verder in; D66 stijgt door; Volt en Ja21 maken goede kans In de meest recente I&O-zetelpeiling – die liep van vrijdag 12 tot maandagochtend 15 maart – zien we de VVD verder inleveren (van 36 naar 33 zetels) en D66 verder stijgen (van 16 naar 19 zetels). Bij peilingen (steekproefonderzoek) moet rekening gehouden worden met onnauwkeurigheids- marges. Voor VVD (21,0%, marge 1,6%) en D66 (11,8%, marge 1,3%) zijn dat (ruim) 2 zetels. De verschuiving voor D66 is statistisch significant, die voor VVD en PvdA zijn dat nipt. Als we naar deze zetelpeiling kijken – 2 dagen voor de verkiezingen – valt op hoezeer hij lijkt op de uitslag van de Tweede Kamerverkiezingen van 2017. Van de winst die de VVD boekte in de coronacrisis is niets over: nu 33 zetels, vier jaar geleden ook 33 zetels. -

Het Eindverslag Downloaden

(On)zichtbare invloed verslag parlementaire ondervragingscommissie naar ongewenste beïnvloeding uit onvrije landen 35 228 Parlementaire ondervraging ongewenste beïnvloeding uit onvrije landen Nr. 4 BRIEF VAN DE PARLEMENTAIRE ONDERVRAGINGSCOMMISSIE Aan de Voorzitter van de Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal Den Haag, 25 juni 2020 De Parlementaire ondervragingscommissie ongewenste beïnvloeding uit onvrije landen (POCOB), biedt u hierbij het verslag «(On)zichtbare invloed» aan van de parlementaire ondervraging die zij op grond van de haar op 2 juli 2019 gegeven opdracht (Kamerstuk 35 228, nr. 1) heeft uitgevoerd. De verslagen van de verhoren die onder ede hebben plaatsgevonden, zijn als bijlage toegevoegd.1 De voorzitter van de commissie, Rog De griffier van de commissie, Sjerp 1 Kamerstuk II 2019/20, 35 228, nr. 5. pagina 1 /238 pagina 2 /238 De leden van de de Parlementaire ondervragingscommissie ongewenste beïnvloeding uit onvrije landen parlementaire in de Enquêtezaal op 6 februari 2020 van links naar rechts: R.A.J. Schonis, T. Kuzu, C.N. van den Berge, G.J.M. Segers , A. de Vries , M.R.J. Rog, C. Stoffer, E. Mulder (op 4 juni 2020 door de Kamer ontslag verleend uit de commissie) en A.A.G.M. van Raak. De leden en s taf van de de Parlementaire ondervragingscommissie ongewenste beïnvloeding uit onvrije landen parlementaire in de Enquêtezaal op 6 februari 2020 van links naar rechts: H.M. Naaijen, M.I.L. Gijsberts, R.A.J. Schonis, T. Kuzu, M.E.W. Verhoeven, C.N. van den Berge, L.K. Mi ddel hov en, G.J.M. Segers , E.M. Sj erp, W.J. -

Mensenrechten in Nederland

JAARLIJKSE RAPPORTAGE MENSENRECHTEN IN NEDERLAND ‘ Het is de taak van de overheid om ervoor te zorgen dat de bescherming van mensenrechten voortdurend verbetert.’ College voor de Rechten van de Mens Kleinesingel 1-3 Postbus 16001 3500 DA Utrecht T 030 888 38 88 Teksttelefoon: 030 888 38 29 F 030 888 38 83 E [email protected] W www.mensenrechten.nl Voor vragen kunt u een e-mail sturen en op werkdagen bellen van 10.00 - 16.00 uur. Inhoud Voorwoord 6 1 Samenvatting en aanbevelingen 9 1.1 Mensenrechten voor iedereen? 10 1.2 Huisvesting 11 1.3 Het recht op goed onderwijs op basis van gelijke kansen 12 1.4 Zorg en ondersteuning voor volwassenen 13 1.5 De flexibele arbeidsmarkt 14 1.6 Geweld tegen minderjarigen en vrouwen 15 1.7 De vrijheid van meningsuiting, persvrijheid en demonstratievrijheid 16 1.8 Veiligheidsrisico’s en mensenrechten 17 1.9 De vrijheid van godsdienst 18 1.10 Toegang tot het recht en vrijheidsbeneming 19 1.11 Het VN-verdrag handicap 20 2 Mensenrechten voor iedereen? 23 2.1 Iedereen heeft mensenrechten 25 2.2 Mensenrechten echt voor iedereen? 26 2.3 Wie heeft de verantwoordelijkheid? 30 2.4 Waar kun je terecht als het misgaat? 32 2.5 Mensenrechten de komende vijf jaar als uitgangspunt 34 3 Huisvesting 37 3.1 Inleiding 39 3.2 Ontwikkeling: huizenmarkt is aangetrokken 39 3.3 Beschikbaarheid, betaalbaarheid en kwaliteit vloeien voort uit recht op huisvesting 39 3.4 Ontwikkeling: problemen met beschikbaarheid, betaalbaarheid en kwaliteit van huisvesting 40 3.5 Ontwikkeling: dakloosheid is een ernstig probleem 42 3.6 Conclusie -

D66 Morrelt Aan Vrijheid, Democratie En Burgerrechten

D66 morrelt aan vrijheid, democratie en burgerrechten Door Coen de Jong - 7 maart 2020 Geplaatst in D66 - Democratie D66 werpt zichzelf graag op als de hoeder van de rechtsstaat, de vrijheid en de democratie tegenover het oprukkende populisme. Vicepremier en minister van Binnenlandse Zaken Kajsa Ollongren sprak in 2018 in een lezing: ‘Het populisme wil sommige Nederlanders anders behandelen dan andere. En daarmee bedreigt het kernwaarden van Nederland’. Woorden gericht aan het adres van oppositiepartij Forum voor Democratie. D66 wilde bij oprichting een alternatief zijn voor het vermolmde Nederlandse partijstelsel. D66 stond voor bestuurlijke vernieuwing, inspraak van de burger in plaats van handjeklap tussen verzuilde elites en voor het kiezen van burgemeesters. Directe democratie, zoals via referenda, stond ook hoog aangeschreven. En D66 zag zichzelf als vanaf het begin in 1966 pragmatisch en later tevens als ‘redelijk alternatief’. Het hoogtepunt van D66 waren de ‘paarse’ coalities in de jaren negentig waarbij D66 het CDA uit de regering wist te houden. Maar in 2006 wist lijsttrekker Alexander Pechtold – geen succes als minister van Bestuurlijke Vernieuwing – met moeite drie Kamerzetels te halen. Maar de redding was nabij. Pechtold positioneerde D66 tegenover de PVV en Geert Wilders, wat hem populair maakte bij journalisten én progressieve kiezers. Deelname in 2017 aan Rutte-3 betekende voor D66 de terugkeer in het centrum van de macht. Alleen: van de oorspronkelijke principes en van bestuurlijke vernieuwing hoorden we niets meer. Integendeel, het raadgevend referendum sneuvelde uitgerekend met Kajsa Ollongren op Binnenlandse Zaken. De website van D66 beschrijft de uitgangspunten van de partij in vijf vage ‘richtingwijzers’ over Wynia's week: D66 morrelt aan vrijheid, democratie en burgerrechten | 1 D66 morrelt aan vrijheid, democratie en burgerrechten duurzaamheid, harmonie en vertrouwen. -

Freewave-456

FREEWAVE • maandelijks mediamagazine Jaargang 34 — nummer 456 — november 2011 COLOFON Exploitatie: Stichting Media Communicatie Beste lezers, Hoofdredacteur: Hans Knot Misschien waren de mankementen aan de zendmas- Lay-out: Jan van Heeren ten de afgelopen zomer wel tekenend voor de situatie Druk: EPC in omroepland. Niet alleen de mast in Smilde brok- kelde af, ook de omroepzuilen lijken een zelfde lot Vaste medewerkers: te ondergaan met de gedwongen fusies in het voor- Michel van Hooff (Nederland); Rene Burck- uitzicht. sen, Jan Hendrik Kruidenier (VS); Jelle Knot Voor Freewave Media Magazine staan er ook veran- (Internationaal); Martin van der Ven (inter- deringen op stapel. Slechts één gedrukt exemplaar netnieuws); Ingo Paternoster (Duitsland); Gijs staat ons nog te wachten. Dan breekt het digitale van den Heuvel (Caribisch Gebied) tijdperk aan. Verantwoordelijke uitgever: Ditmaal starten we zoals gebruikelijk met “Heden en Stichting Media Communicatie, Postbus 53121, verleden”, gevolgd door “Perikelen”. Verder nieuws 1007 RC Amsterdam uit Engeland en de wereld rond. Hans Knot schreef e-mail: [email protected] een artikel over de voorgeschiedenis van een bijzon- web: www.mediacommunicatie.nl der restaurant in Amsterdam: het REM-eiland welte- verstaan! Correspondentieadres: Rob Olthof schrijft in zijn colums over Radio 227 en Hans Knot, over de ruis op de publieke radio. Bert Bossink neemt Populierenlaan 8, 9741 HE Groningen voor de vijfde maal een duik in de voorgeschiedenis e-mail: [email protected] van de Nederbeat en we sluiten af met een aantal www.hansknot.com & www.soundscapes.info boekrecensies. Lidmaatschap: Veel leesplezier, Jan van Heeren De lidmaatschapsprijzen gaan met ingang van 1 ja- nuari 2012 veranderen. -

Prinsjesdagpeiling 2017

Rapport PRINSJESDAGPEILING 2017 Forum voor Democratie wint terrein, PVV zakt iets terug 14 september 2017 www.ioresearch.nl I&O Research Prinsjesdagpeiling september 2017 Forum voor Democratie wint terrein, PVV zakt iets terug Als er vandaag verkiezingen voor de Tweede Kamer zouden worden gehouden, is de VVD opnieuw de grootste partij met 30 zetels. Opvallend is de verschuiving aan de rechterflank. De PVV verliest drie zetels ten opzichte van de peiling in juni en is daarmee terug op haar huidige zetelaantal (20). Forum voor Democratie stijgt, na de verdubbeling in juni, door tot 9 zetels nu. Verder zijn er geen opvallende verschuivingen in vergelijking met drie maanden geleden. Zes op de tien Nederlanders voor ruimere bevoegdheden inlichtingendiensten Begin september werd bekend dat een raadgevend referendum over de ‘aftapwet’ een stap dichterbij is gekomen. Met deze wet krijgen Nederlandse inlichtingendiensten meer mogelijkheden om gegevens van internet te verzamelen, bijvoorbeeld om terroristen op te sporen. Tegenstanders vrezen dat ook gegevens van onschuldige burgers worden verzameld en bewaard. Hoewel het dus nog niet zeker is of het referendum doorgaat, heeft I&O Research gepeild wat Nederlanders nu zouden stemmen. Van de kiezers die (waarschijnlijk) gaan stemmen, zijn zes op de tien vóór ruimere bevoegdheden van de inlichtingendiensten. Een kwart staat hier negatief tegenover. Een op de zes kiezers weet het nog niet. 65-plussers zijn het vaakst voorstander (71 procent), terwijl jongeren tot 34 jaar duidelijk verdeeld zijn. Kiezers van VVD, PVV en de christelijke partijen CU, SGP en CDA zijn in ruime meerderheid voorstander van de nieuwe wet. Degenen die bij de verkiezingen in maart op GroenLinks en Forum voor Democratie stemden, zijn per saldo tegen. -

JA21 VERKIEZINGSPROGRAMMA 2021-2025 Het Juiste Antwoord VOORWOORD

JA21 VERKIEZINGSPROGRAMMA 2021-2025 Het Juiste Antwoord VOORWOORD Net als velen van u zou ik nergens liever willen leven dan hier. Ons mooie land heeft een gigantisch potentieel. We zijn innovatief, nuchter, hardwer- kend, trots op wie we zijn en gezegend met een indrukwekkende geschie- denis en een gezonde handelsgeest. Een Nederland dat Nederland durft te zijn is tot ongekende prestaties in staat. Al sinds de komst van Pim Fortuyn in 2002 laten miljoenen kiezers weten dat het op de grote terreinen van misdaad, migratie, het functioneren van de publieke sector en Europa anders moet. Nederland zal in een uitdijend en oncontroleerbaar Europa meer voor zichzelf moeten kiezen en vertrouwen en macht moeten terugleggen bij de kiezer. Maar keer op keer krijgen rechtse kiezers geen waar voor hun stem. Wie rechts stemt krijgt daar immigratierecords, een steeds verder uitdijende overheid, stijgende lasten, een verstikkend ondernemersklimaat, afschaffing van het referendum en een onbetaalbaar en irrationeel klimaatbeleid voor terug die ten koste gaan van onze welvaart en ons woongenot. Ons programma is een realistische conservatief-liberale koers voor ieder- een die de schouders onder Nederland wil zetten. Positieve keuzes voor een welvarender, veiliger en herkenbaarder land waarin we criminaliteit keihard aanpakken, behouden wat ons bindt en macht terughalen uit Europa. Met een overheid die er voor de burgers is en goed weet wat ze wel, maar ook juist niet moet doen. Een land waarin we hart hebben voor wie niet kan, maar hard zullen zijn voor wie niet wil. Wij zijn er klaar voor. Samen met onze geweldige fracties in de Eerste Kamer, het Europees Parlement en de Amsterdamse gemeenteraad én met onze vertegenwoordigers in de Provinciale Staten zullen wij na 17 maart met grote trots ook uw stem in de Tweede Kamer gaan vertegenwoordigen. -

Factsheet: the Dutch House of Representatives Tweede Kamer 1

Directorate-General for the Presidency Directorate for Relations with National Parliaments Factsheet: The Dutch House of Representatives Tweede Kamer 1. At a glance The Netherlands is the main constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, with its monarch King Willem-Alexander. Since 1848 it has been governed as a parliamentary democracy and a constitutional monarchy, organised as a unitary state. The Dutch Parliament "Staten-Generaal" is a bicameral body. It consists of two chambers, both of which are elected for four-year terms. The Senate, the Eerste Kamer is indirectly elected. It consists of 75 members and is elected by the (directly elected) members of the 12 provincial state councils, known as the "staten". The 150 members of the House of Representatives, the Tweede Kamer, are directly elected through a national party-list system, on the basis of proportional representation. On 26 October 2017 the third Cabinet of Prime Minister Mark Rutte took office. Four political parties formed the governing coalition: People's Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD), Christian Democratic Appeal (CDA), Democrats 66 (D66) and Christian Union (CU). On 15 January 2021 the government resigned over the child benefits affair. The government will stay on in caretaker capacity until general elections scheduled for 17 March 2021. 2. Composition Results of the parliamentary elections of 15 March 2017 and current redistribution of seats Party EP % Seats affiliation Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie (VVD) 321 People's Party for Freedom and Democracy 21,3% (33) Partij Voor de Vrijheid (PVV) Party for Freedom 13,1% 20 Christen Democratisch Appèl (CDA) Christian Democratic Appeal 12,4% 19 Democraten 66 (D66) Democrats 66 12,2% 19 1 In 2019, Wybren van Haga, was expelled from the VVD. -

Citizenship, Structural Inequality and the Political Elite

Citizenship, Structural Inequality and The Political Elite Michael S. Merry (University of Amsterdam) The class that is the ruling material force of society is at the same time the ruling intellectual force. Karl Marx Wherever there is an ascendant class, a large portion of the morality of the country emanates from its class interests and its feelings of class superiority. John Stuart Mill For a long time now, liberal theorists have championed the belied by the conditions of deep structural inequality idea that citizenship is the task of the school. endemic to most schools, and indeed to entire school Notwithstanding substantive disagreement among these systems. It is also belied by the ways in which most schools theorists, all liberal accounts share the same basic faith are designed to promote and reward competition, rule concerning both the duty and the ability of schools to do compliance, deference to authority and nationalist loyalty. what their theories require. Matthew Clayton’s highly These problems are further exacerbated by the un- idealized philosophical account is representative; he preparedness and unwillingness of most teachers to confidently asserts that civic education in schools ought to facilitate ‘deliberative interactions’ in classrooms of diverse prepare background and opinion, not to mention parents who do not want their child’s education ‘politicized’. “deliberative citizens [to] display a set of skills and Of course, this empirical state of affairs does not virtues related to deliberative interaction: skills related foreclose possibilities for normative argument, nor does it to articulating a position and the reasons for its prevent us from imagining incremental improvements. -

Canon DR-G1100 Serienr. 21GGJ01978

4 Model N 10-1 - Proces-verbaal van een stembureau 1 / 65 Model N 10-1 Proces-verbaal van een stembureau De verkiezing van de leden van Tweede Kamerverkiezing 2021 op woensdag 17 maart 2021 Gemeente Helmond Kieskring 18 Wa arom een proces-verbaal? Elk stembureau maakt bij een verkiezing een proces-verbaal op. Met het proces-verbaal legt het stembureau verantwoording af over het verloop van de stemming en over de telling van de stemmen. Op basis van de processen-verbaal wordt de uitslag van de verkiezing vastgesteld. Vul het proces-verbaal daarom altijd juist en volledig in. Na de stemming mogen kiezers het proces-verbaal inzien. Zo kunnen zij nagaan of de stemming en de telling van de stemmen correct verlopen zijn. Wie vullen het proces-verbaal in en ondertekenen het? Alle stembureauleden zijn verantwoordelijk voor het correct en volledig invullen van het proces-verbaal. Na afloop van de telling van de stemmen ondertekenen alle stembureauleden die op dat moment aanwezig zijn het proces-verbaal. Dat zijn in elk geval de voorzitter van het stembureau en minimaal twee andere stembureauleden. 1. Locatie en openingstijden stembureau A Als het stembureau een nummer heeft, vermeld dan het nummer 502 B Op welke datum vond de stemming plaats? Datum 17-03-2021 van O 1 3 I O tot 2 ±A 3 I O uur. C Waar vond de stemming plaats? Openingstijden voor kiezers Adres of omschrijving locatie van GEMEENSCHAPSHUIS DE LOOP, Peeleik 7, 5704 AP Helmond uur 07 l3o D Op welke datum vond de telling plaats? 2 \ Datum \~7 ' C> 3' van ^ | : ^IQ tot () I tl pl Q uur. -

Pleidooi Voor Ethische Crisiscommunicatie

“Het gaat om de relatie, niet om de reputatie” Pleidooi voor ethische crisiscommunicatie Door Frank Vergeer en Nico de Leeuw Met dank aan Frank Regtvoort, Jan Merton en Anne-Marie van het Erve Inhoudsopgave Probleemstelling & samenvatting 3 1 Belangrijke ontwikkelingen 4 1.1 Vertrouwen all time low 5 1.2 Transparantie en verantwoording 6 2 Reputatie versus publiek belang 7 2.1 Definitie ethische crisiscommunicatie 7 2.2 Omgevingsanalyse als basis 8 2.3 De circel van getroffenen 9 2.4 Succesvolle voorbeelden 11 2.5 Communiceren voor vertrouwen 12 2.6 Struisvogelgedrag een herhalend patroon 15 2.7 Lastig vinger op te leggen 18 2.8 Burgemeesters en hun reputatie 19 2.9 De corruptie in woningcorporatieland 21 2.10 De toeslagenaffaire 21 2.11 Paard achter de wagen spannen 24 3 De verschillen op een rijtje 26 4 Conclusies 28 Over de auteurs 30 Bronnenoverzicht 31 PLEIDOOI VOOR ETHISCHE CRISISCOMMUNICATIE 2 Probleemstelling en samenvatting Binnen de communicatieberoepswereld wordt crisiscommunicatie verward met reputatiemanagement, terwijl dit toch twee totaal verschillende vakgebieden zijn. Geclaimd wordt door reputatieprofessionals de juiste aanpak en oplossingen te hebben voor kwesties die crisiscommunicatie behoeven. Echter, de doelstelling en aanpak die wordt gehanteerd, is niet vergelijkbaar met die van crisiscommuni- catie professionals. Bij reputatiemanagement ligt de focus op de organisatie: hoe komt die er zo ongeschonden mogelijk uit. Bij crisiscommunicatie staan de getroffenen centraal. In feite is er sprake van een belangenconflict tussen twee verschillende soorten vakgebieden die zich met dezelfde soort kwesties bezig houden. Het belang van het publiek en de betrokkenen versus het belang van de organisatie of instantie waar de kwestie speelt.