Apostles of Abstinence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Monasteries

Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Monasteries Atlas of Whether used as a scholarly introduction into Eastern Christian monasticism or researcher’s directory or a travel guide, Alexei Krindatch brings together a fascinating collection of articles, facts, and statistics to comprehensively describe Orthodox Christian Monasteries in the United States. The careful examina- Atlas of American Orthodox tion of the key features of Orthodox monasteries provides solid academic frame for this book. With enticing verbal and photographic renderings, twenty-three Orthodox monastic communities scattered throughout the United States are brought to life for the reader. This is an essential book for anyone seeking to sample, explore or just better understand Orthodox Christian monastic life. Christian Monasteries Scott Thumma, Ph.D. Director Hartford Institute for Religion Research A truly delightful insight into Orthodox monasticism in the United States. The chapters on the history and tradition of Orthodox monasticism are carefully written to provide the reader with a solid theological understanding. They are then followed by a very human and personal description of the individual US Orthodox monasteries. A good resource for scholars, but also an excellent ‘tour guide’ for those seeking a more personal and intimate experience of monasticism. Thomas Gaunt, S.J., Ph.D. Executive Director Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA) This is a fascinating and comprehensive guide to a small but important sector of American religious life. Whether you want to know about the history and theology of Orthodox monasticism or you just want to know what to expect if you visit, the stories, maps, and directories here are invaluable. -

After the Wedding Night: the Confluence of Masculinity and Purity in Married Life Sarah H. Diefendorf a Thesis Submitted in Part

After the Wedding Night: The Confluence of Masculinity and Purity in Married Life Sarah H. Diefendorf A thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Washington 2012 Committee: Pepper Schwartz Julie Brines Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Department of Sociology University of Washington Abstract After the Wedding Night: The Confluence of Masculinity and Purity in Married Life Sarah H. Diefendorf Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Pepper Schwartz Department of Sociology Purity is congruent with cultural understandings of femininity, but incongruent with normative definitions of masculinity. Using longitudinal qualitative data, this study analyzes interviews with men who have taken pledges of abstinence pre and post marriage, to better understand the ways in which masculinity is asserted within discourses of purity. Building off of Wilkins’ concept of collective performances of temptation and Luker’s theoretical framing of the “sexual conservative” I argue that repercussions from collective performances of temptation carry over into married life; sex is thought of as something that needs to be controlled both pre and post marriage. Second, because of these repercussions, marriage needs to be re-conceptualized as a “verb”; marriage is not a static event for sexual liberals or sexual conservatives. The current study highlights the ways in which married life is affected by a pledge of abstinence and contributes to the theoretical framing of masculinities as fluid. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to thank Pepper Schwartz and Julie Brines for their pointed feedback and consistent encouragement and enthusiasm for this research. The author would also like to thank both Aimée Dechter and the participants of the 2011-2012 Masters Thesis Research Seminar for providing the space for many lively, helpful discussions about this work. -

7Th Grade 3.06 Define Abstinence As Voluntarily Refraining from Intimate

North Carolina Comprehensive School Health Training Center 3/07 C. 7th grade 3.06 Define abstinence as voluntarily refraining from intimate sexual contact that could result in unintended pregnancy or disease and analyze the benefits of abstinence from sexual until marriage. 7th grade 3.08 Analyze the effectiveness and failure rates of condoms as a means of preventing sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV/AIDS. 8th grade 3.08 Compare and contrast methods of contraception, their effectiveness and failure rates, and the risks associated with different methods of contraception, as a means of preventing sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV/AIDS. Materials Needed: Appendix 1 – Conception Quiz/STD Quiz – Teacher’s Key desk bells Appendix 2 – transparency of quotes about risk taking Appendix 3 – transparency of Effectiveness Rates for Contraceptive Methods Appendix 4 – background information on condom efficacy Appendix 5 – signs and cards for Contraceptive Effectiveness (cut apart) Appendix 6 – copies of What Would You Say? Review: Ask eight students to come to the front of the room and form two teams of four. They are to line up so they can ring in to answer questions using the Conception Quiz – Teacher’s Key for Appendix 1. Assign another student to determine who rings in first and explain they cannot ring in until they have heard the entire question. Each student will answer a question, go to the end of the line, and then have a second turn answering a question. If the question can be answered “yes” or “no,” they are to explain “why” or “why not.” Ask another eight students to come to the front and repeat the activity using the STD Quiz – Teacher’s Key. -

Abstinence Education in Context: History, Evidence, Premises, and Comparison to Comprehensive Sexuality Education

IN MAUREEN KENNY (ED.) (2014). SEX EDUCATION. HAUPPAUGE, NY: NOVA SCIENCE PUBLISHERS. WWW.NOVAPUBLISHERS.COM ABSTINENCE EDUCATION IN CONTEXT: HISTORY, EVIDENCE, PREMISES, AND COMPARISON TO COMPREHENSIVE SEXUALITY EDUCATION Stan E. Weed, Ph.D. The Institute for Research and Evaluation Thomas Lickona, Ph.D. Center for the 4th and 5th Rs (Respect and Responsibility) School of Education, State University of New York at Cortland ABSTRACT This chapter provides a broad picture of the abstinence education movement in the U.S. and the historical, political, and theoretical context of its journey. It describes the problems it has targeted, the policies and programs it has designed to solve them, and the results of these various interventions. Solutions to the problems posed by adolescent sexual activity have fallen into three camps: risk reduction, risk avoidance, and a combination of those two approaches. This historical context permits a comparative analysis of the most common sex education strategies and provides a better understanding of what abstinence education actually looks like—what it is and what it is not. In addition to describing the outcomes of the different approaches to sex education, we examine their foundational premises and assumptions, with the intent to clarify not only what does or does not work but also the reasons for success or failure. As important as the effectiveness question is, the underlying rationale, theory, or premise on which any program strategy is based is equally important if we are to understand how to benefit from prior successes and failures. In addressing these issues, we propose and describe an empirical model that delineates key predictors of adolescent risk behavior and demonstrates important causal mechanisms that program developers can focus on for more effective interventions. -

Fear, Power, & Teeth (2007)

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Graduate School Professional Papers 2019 Fear, Power, & Teeth (2007) Olivia Hockenbroch Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Social Influence and Political Communication Commons, Speech and Rhetorical Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hockenbroch, Olivia, "Fear, Power, & Teeth (2007)" (2019). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 11326. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/11326 This Professional Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running Head: FEAR, POWER, AND TEETH (2007) FEAR, POWER, & TEETH (2007) By OLIVIA ANNE HOCKENBROCH Communication with Philosophy Bachelor of Arts Juniata College, Huntingdon, PA 2015 Professional Paper Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In Communication Studies, Rhetoric & Public Discourse The University of Montana Missoula, MT May 2019 Approved by: Dr. Greg Larson, Chair Department of Communication Studies Dr. Sara Hayden, Advisor Department of Communication Studies Dr. Betsy BacH Department of Communication Studies Dr. Kathleen Kane Department of English FEAR, POWER, AND TEETH (2007) 1 Fear, Power, and Teeth (2007) Literature Review Vagina dentata is the myth of the toothed vagina; in most iterations, it serves as a warning to men that women’s vaginas must be conquered to be safe for a man’s sexual pleasure (Koehler, 2017). -

Benefits of Sexual Expression

White Paper Published by the Katharine Dexter McCormick Library Planned Parenthood Federation of America 434 W est 33rd Street New York, NY 10001 212-261-4779 www.plannedparenthood.org www.teenwire.com Current as of July 2007 The Health Benefits of Sexual Expression Published in Cooperation with the Society for the Scientific Study of Sexuality In 1994, the 14th World Congress of Sexology with the vast sexological literature on dysfunction, adopted the Declaration of Sexual Rights. This disease, and unwanted pregnancy, we are document of “fundamental and universal human accumulating data to begin to answer many rights” included the right to sexual pleasure. This questions about the potential benefits of sexual international gathering of sexuality scientists expression, including declared, “Sexual pleasure, including autoeroticism, • What are the ways in which sexual is a source of physical, psychological, intellectual expression benefits us physically? and spiritual well-being” (WAS, 1994). • How do various forms of sexual expression benefit us emotionally? Despite this scientific view, the belief that sex has a • Are there connections between sexual negative effect upon the individual has been more activity and spirituality? common in many historical and most contemporary • Are there positive ways that early sex play cultures. In fact, Western civilization has a affects personal growth? millennia-long tradition of sex-negative attitudes and • How does sexual expression positively biases. In the United States, this heritage was affect the lives of the disabled? relieved briefly by the “joy-of-sex” revolution of the • How does sexual expression positively ‘60s and ‘70s, but alarmist sexual viewpoints affect the lives of older women and men? retrenched and solidified with the advent of the HIV • Do non-procreative sexual activities have pandemic. -

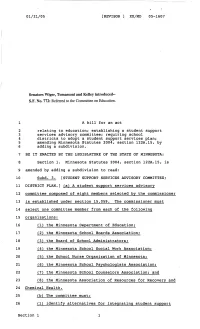

1 a Bill for an .Act 05-1607 2 Relating to Education

01/21/05 [REVISOR ] XX/MD 05-1607 Senators Wiger, Tomassoni and Kelley introduced- S.F. No. 772: Referred to the Committee on Education. 1 A bill for an .act 2 relating to education; establishing a student support 3 services advisory committee; requiring school 4 districts to adopt a student support services plan; 5 amending Minnesota Statutes 2004, section 122A.15, by 6 adding a subdivision. 7 BE IT ENACTED BY THE LEGISLATURE OF THE STATE OF MINNESOTA: 8 Section 1. Minnesota Statutes 2004, section 122A.15, is 9 amended by adding a subdivision to read: 10 Subd. 3. [STUDENT SUPPORT SERVICES ADVISORY COMMITTEE; 11 DISTRICT PLAN.] (a) A student support services advisory 12 committee composed of eight members selected by .the commissioner 13 is established under section 15.059. The commissioner must 14 select one committee member from each of the following 15 organizations: 16 (1) the Minnesota Department of Education; 17 (2) the Minnesota School Boards Association; 18 (3) the Board of School Administrators; 19 (4) the Minnesota School Social Work Association; 20 (5) the School Nurse Organization of Minnesota; 21 (6) the Minnesota School Psychologists Association; 22 (7) the Minnesota School Counselors Association; and 23 (8) the Minnesota Association of Resources for Recovery and 24 Chemical Health. 25 (b) The committee must: 26 (1) identify alternatives for integrating student support Section 1 1 01/21/05 [REVISOR ] XX/MD 05-1607 1 services into public schools; 2 (2) recommend support staff to student ratios and best 3 practices for providing student support services premised on 4 valid, widely recognized research; 5 (3) identify the substance and extent of the work that 6 . -

CROSSLING, LOVE L., Ph.D. Abstinence Curriculum in Black Churches: a Critical Examination of the Intersectionality of Race, Gender, and SES

CROSSLING, LOVE L., Ph.D. Abstinence Curriculum in Black Churches: A Critical Examination of the Intersectionality of Race, Gender, and SES. (2009) Directed by Dr. Kathleen Casey. 243 pp. Current sex education curriculum focuses on pregnancy and disease, but very little of the curriculum addresses the social, emotional, or moral elements. Christian churches have made strides over the last two decades to design an abstinence curriculum that contains a moral strand, which addresses spiritual, mental, social, and emotional challenges of premarital sex for youth and singles. However, many black churches appear to be challenged in four areas: existence, purpose, developmental process, and content of teaching tools at it relates to abstinence curriculum. Existence refers to whether or not a church body deems it necessary or has the available resources to implement an abstinence curriculum. Purpose refers to the overall goals and motivations used to persuade youth and singles. Developmental process describes communicative power dynamics that influence the recognized voices at the decision-making table when designing a curriculum. Finally, content of teaching tools refers to prevailing white middle class messages found in Christian inspirational abstinence texts whose cultural irrelevance creates a barrier in what should be a relevant message for any population. The first component of the research answers the question of why the focus should be black churches by exploring historical and contemporary distinctions of black sexuality among youth and single populations. The historical and contemporary distinctions are followed by an exploration of how the history of black church development influenced power dynamics, which in turn affects the freedom with which black Christian communities communicate about sexuality in the church setting. -

Purity for Life Handout for Parents

Purity for Life Handout for Parents Milestone 4: Purity for Life Welcome to Purity for Life. The goal of this seminar is to take a holistic approach to purity in all of life according to Scripture and to prepare families to celebrate the Milestone: Purity for Life together. God has said a great deal concerning purity in the life of every believer. As adolescence flows into everyday life, the issue of purity will be one that can literally alter life’s course for teenagers. A commitment to physical purity is only part of the story. Without addressing the underlying issues, committing to sexual abstinence will be hollow and often broken. God created the human heart, soul, mind and strength to work cohesively to bring Him glory by following His path for life. Purity for Life is guiding your kids along the path that God has laid for them. “I appeal to you therefore, brothers, by the mercies of God, to present your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and acceptable to God, which is your spiritual worship. Do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewal of our mind, that by testing you may discern what is the will of God, what is good and acceptable and perfect.” Romans 12:1-2 The Adolescent Pressures of Life During Milestone 3, the pressures of life on adolescents are discussed in detail. These pressures highly impact this roller coaster ride of emotions, hormones and physical development. Influence from every aspect of life is attempting to define your child’s worth and purpose. -

About Outing: Public Discourse, Private Lives

Washington University Law Review Volume 73 Issue 4 January 1995 About Outing: Public Discourse, Private Lives Katheleen Guzman University of Oklahoma Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview Part of the First Amendment Commons Recommended Citation Katheleen Guzman, About Outing: Public Discourse, Private Lives, 73 WASH. U. L. Q. 1531 (1995). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol73/iss4/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABOUT OUTING: PUBLIC DISCOURSE, PRIVATE LIVES KATHELEEN GUZMAN* Out of sight, out of mind. We're here. We're Queer. Get used to it. You made your bed. Now lie in it.' I. INTRODUCTION "Outing" is the forced exposure of a person's same-sex orientation. While techniques used to achieve this end vary,2 the most visible examples of outing are employed by gay activists in publications such as The Advocate or OutWeek,4 where ostensibly, names are published to advance a rights agenda. Outing is not, however, confined to fringe media. The mainstream press has joined the fray, immortalizing in print "the love[r] that dare[s] not speak its name."' The rules of outing have changed since its national emergence in the early 1990s. As recently as March of 1995, the media forced a relatively unknown person from the closet.6 The polemic engendered by outing * Associate Professor of Law, University of Oklahoma College of Law. -

This Is Who I Am: a Phenomenological Analysis of Female Purity Pledgers’ Sense of Identity and Sexual Agency

THIS IS WHO I AM: A PHENOMENOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF FEMALE PURITY PLEDGERS’ SENSE OF IDENTITY AND SEXUAL AGENCY by KATRINA N. HANNA B.A., Arkansas Tech University, 2010 A THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of Communication Studies College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2016 Approved by: Major Professor Dr. Soo-Hye Han Abstract At the turn of the 21st century, an ideological movement defined by many as the modesty movement helped push sexual abstinence as a controversial yet significant public issue in the United States. Concerned with a “hyper-sexualized” culture, modesty advocates urged young women to make a pledge to remain pure until marriage. Following the the growth of the movement, feminist scholars have been critical of the movement and the potentially detrimental consequences of purity pledges on young women’s identity, sexuality, and sexual agency. This study takes a step back from this critical view of purity pledges and listens to young women’s lived experience of making a purity pledge and living a life of purity. Specifically, this study asks how purity pledgers understand and enact purity and how they perceive their sexuality and sexual agency. To answer these questions, qualitative interviews were conducted with nine young women who at some point in their life made a purity pledge. A thematic analysis revealed three major themes: 1) living a pure life is situated within multifaceted perspectives on purity, 2) living a life of purity consists of negotiating multiple “selves,” and 3) living a life of purity grants and reinforces a sense of agency. -

A Magazine About Acadia National Park and Surrounding Communities 13 1149.Qxd:13 1149 7/26/13 9:34 AM Page Cvr2

13_1149.qxd:13_1149 7/26/13 9:34 AM Page Cvr1 Summer 2013 Volume 18 No. 2 A Magazine about Acadia National Park and Surrounding Communities 13_1149.qxd:13_1149 7/26/13 9:34 AM Page Cvr2 PURCHASE YOUR PARK PASS! Whether driving, walking, bicycling, or riding the Island Explorer through the park, we all must pay the entrance fee. Eighty percent of all fees paid in the park stay in the park, to be used for projects that directly benefit park visitors and resources. The Acadia National Park $20 weekly pass ($10 in the off-season) and $40 annual pass are available at the following locations: Open in the Off-Season: ~ Acadia National Park Headquarters (Eagle Lake Road) Open through November: ~ Hulls Cove Visitor Center ~ Thompson Island Information Center ~ Bar Harbor Village Green Bus Center ~ Sand Beach Entrance Station ~ Blackwoods and Seawall Campgrounds ~ Jordan Pond and Cadillac Mountain Gift Shops For more information visit www.friendsofacadia.org 13_1149.qxd:13_1149 7/31/13 5:18 PM Page 1 President’s Message LESSONS FROM CADILLAC s I swung my bike off the Park Loop summit to vehicles a week earlier than orig- and onto the Cadillac Summit Road, inally forecasted. But overall, far too many A I entered a cool pocket of shade. The people concluded that without all motor road narrowed here and the hemlock trees roads open to cars, “Acadia was closed,” and grew taller. The gurgle of a stream reached many businesses and visitors lost out as a my ears from the dense woods on either side result.