About Outing: Public Discourse, Private Lives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hrc-Coming-Out-Resource-Guide.Pdf

G T Being brave doesn’t mean that you’re not scared. It means that if you are scared, you do the thing you’re afraid of anyway. Coming out and living openly as a lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender or supportive straight person is an act of bravery and authenticity. Whether it’s for the first time ever, or for the first time today, coming out may be the most important thing you will do all day. Talk about it. TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 Welcome 3 Being Open with Yourself 4 Deciding to Tell Others 6 Making a Coming Out Plan 8 Having the Conversations 10 The Coming Out Continuum 12 Telling Family Members 14 Living Openly on Your Terms 15 Ten Things Every American Ought to Know 16 Reference: Glossary of Terms 18 Reference: Myths & Facts About LGBT People 19 Reference: Additional Resources 21 A Message From HRC President Joe Solmonese There is no one right or wrong way to come out. It’s a lifelong process of being ever more open and true with yourself and others — done in your own way and in your own time. WELCOME esbian, gay, bisexual and transgender Americans Lare sons and daughters, doctors and lawyers, teachers and construction workers. We serve in Congress, protect our country on the front lines and contribute to the well-being of the nation at every level. In all that diversity, we have one thing in common: We each make deeply personal decisions to be open about who we are with ourselves and others — even when it isn’t easy. -

Queer Theorists and Gay Journalists Wrestle Over

PLEASURE PRIPRINCIPLES BY CALEB CRAIN QUEER THEORISTS AND GAY JOURNALISTS WRESTLE OVER THE POLITICS OF SEX 26 PLEASURE PRINCIPLES PLEASURE PRIPRINCIPLES Nearly two hundred men and women have come to sit in the sweaty ground-floor assembly hall of New York City’s Lesbian and Gay Community Services Cen- ter. They’ve tucked their gym bags under their folding chairs, and, despite the thick late-June heat, they’re fully alert. Doz- ens more men and women cram the edges of the room, leaning against manila-colored card tables littered with Xerox- es or perching on the center’s grade-school-style water foun- tain, a row of three faucets in a knee-high porcelain trough. A video camera focuses on the podium, where activist Gregg Gonsalves and Columbia University law professor Kendall Thomas welcome the audience to a teach-in sponsored by the new organization Sex Panic. It might have been the Sex Panic flyer reading DANGER! ASSAULT! TURDZ! that drew this crowd. Handed out in New York City’s gay bars and coffee shops, the flyer identified continuing HIV transmission as the danger. It pointed to the recent closing of gay and transgender bars and an increase in arrests for public lewdness as the assault. And it named gay writers Andrew Sullivan, Michelangelo Signorile, Larry Kramer, and Gabriel Rotello as the Turdz. The flyer, however, is not how I first Kramer, or Sullivan with hisses, boos, thing called queer theory. Relatively found out about the Sex Panic meeting. and laughs. The men and women here new, queer theory represents a para- A fellow graduate student recommend- tonight feel sure of their enemies, and as digm shift in the way some scholars are ed it to me as a venue for academic the evening advances, these enemies thinking about homosexuality. -

Manchester Pride Festival 2019 Accessibility Information Pack the Team at Manchester Pride Think It Important That Everyone

Manchester Pride Festival 2019 Accessibility information Pack The team at Manchester Pride think it important that everyone who attends The Festival can enjoy the event. As such we have put together information to help you plan and prepare for your visit to The Festival. __________________________________________________ Welcome to The Manchester Pride Parade 2019. What was once a march in protest and a cry for equality, The Manchester Pride Festival is now a hugely anticipated staple event in the city that recognizes how far LGBT+ rights have moved on, yet a political reminder that there is still work to do, as the diverse LGBT+ communities strive for total equality, both here and abroad. Each and every one of you helps us turn the city of Manchester into a kaleidoscope of colour, placing you at the heart of the celebrations and demonstrates to the world that Manchester is a city proud of its diverse communities. Manchester Pride Festival 2019 will be made up of; Manchester Pride Live, the Superbia Weekend, the Gay Village Party, Manchester Pride Parade, Youth Pride MCR and the Candlelit Vigil. Our internationally renowned event will come alive across the city, on a scale never before seen. Stretching from Mayfield to Deansgate with our heart in The Village. An unforgettable weekend awaits. __________________________________________________ Getting to the event Manchester enjoys first-class transport links, making it easy to get to the city, The Festival and for exploring Greater Manchester. For travel information to get to Manchester please visit here. For travel around Manchester once you arrive in our fabulous city, there are a number of transport networks to choose from: Metrolink Manchester's light tramway system runs a fast and frequent service and is ideal for getting to The Festival. -

The Trevor Project’S Coming Out: a Handbook Are At

COMING OUT A Handbook for LGBTQ Young People CONTENTS IDENTITY 4 HEALTHY RELATIONSHIPS 17 THE BASICS 4 SELF-CARE 18 What Is Sex Assigned at Birth? 5 Checking in on Your Mental Health 19 What Is Gender? 5 Warning Signs 19 Gender Identity 6 RESOURCES 20 Gender Expression 7 Transitioning 8 TREVOR PROGRAMS 21 What Is Sexual Orientation? 9 Map Your Own Identity 21 Sexual Orientation 10 Sexual/Physical Attraction 11 Romantic Attraction 12 Emotional Attraction 13 COMING OUT 14 Planning Ahead 14 Testing The Waters 15 Environment 15 Timing 15 Location 15 School 16 Support 16 Safety Around Coming Out 16 2 Exploring your sexual orientation Some people may share their identity with a few trusted friends online, some may choose to share and/or gender identity can bring up a lot with a counselor or a trusted family member, and of feelings and questions. Inside this handbook, others may want everyone in their life to know we will work together to explore your identity, about their identity. An important thing to know what it might be like to share your identity with is that for a lot of people, coming out doesn’t just others, and provide you with tools and guiding happen once. A lot of folks find themselves com- questions to help you think about what coming ing out at different times to different people. out means to you. It is all about what works for you, wherever you The Trevor Project’s Coming Out: A Handbook are at. The things you hear about coming out for LGBTQ Young People is here to help you nav- may make you feel pressured to take steps that igate questions around your identity. -

Every Class in Every School: Final Report on the First National Climate Survey on Homophobia, Biphobia, and Transphobia in Canadian Schools

EVERY CLASS IN EVERY SCHOOL: FINAL REPORT ON THE FIRST NATIONAL CLIMATE SURVEY ON HOMOPHOBIA, BIPHOBIA, AND TRANSPHOBIA IN CANADIAN SCHOOLS RESEARCHERS: CATHERINE TAYLOR (PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR), PH.D., UNIVERSITY OF WINNIPEG AND TRACEY PETER (CO-INVESTIGATOR), PH.D., UNIVERSITY OF MANITOBA Human Rights Trust EVERY CLASS IN EVERY SCHOOL: FINAL REPORT ON THE FIRST NATIONAL CLIMATE SURVEY ON HOMOPHOBIA, BIPHOBIA, AND TRANSPHOBIA IN CANADIAN SCHOOLS RESEARCHERS: CATHERINE TAYLOR (PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR), PH.D., UNIVERSITY OF WINNIPEG AND TRACEY PETER (CO-INVESTIGATOR), PH.D., UNIVERSITY OF MANITOBA RESEARCHERS: PROJECT FUNDERS: Catherine Taylor Egale Canada Human Rights Trust (Principal Investigator), Ph.D., Canadian Institutes of Health Research University of Winnipeg and Tracey Peter (Co-Investigator), Ph.D., The University of Winnipeg SSHRC Research University of Manitoba Grant Program Sexual and Gender Diversity: Vulnerability PROJECT RESEARCH ASSISTANTS: and Resilience (Canadian Institutes for Health TL McMinn, Sarah Paquin, and Kevin Research) Schachter (Senior RAs) Stacey Beldom, Allison Ferry, and Zoe Gross Winnipeg, Manitoba PROJECT ADVISORY PANEL: May 2011 Joan Beecroft, Jane Bouey, James Thank you to The McLean Foundation for so Chamberlain, Ellen Chambers-Picard, Tara kindly supporting the printing and distribution Elliott, Noble Kelly, Wayne Madden, Joan of this report. Merrifield, Elizabeth J. Meyer, Susan Rose, Annemarie Shrouder, and Helen Victoros Human Rights Trust Published by Egale Canada Human Rights Trust 185 Carlton Street, Toronto, ON M5A 2K7 Ph: 1-888-204-7777 Fax: 416-963-5665 Email: [email protected] www.egale.ca When referencing this document, we recommend the following citation: Taylor, C. & Peter, T., with McMinn, T.L., Elliott, T., Beldom, S., Ferry, A., Gross, Z., Paquin, S., & Schachter, K. -

Queer Periodicals Collection Timeline

Queer Periodicals Collection Timeline 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 Series I 10 Percent 13th Moon Aché Act Up San Francisco Newsltr. Action Magazine Adversary After Dark Magazine Alive! Magazine Alyson Gay Men’s Book Catalog American Gay Atheist Newsletter American Gay Life Amethyst Among Friends Amsterdam Gayzette Another Voice Antinous Review Apollo A.R. Info Argus Art & Understanding Au Contraire Magazine Axios Azalea B-Max Bablionia Backspace Bad Attitude Bar Hopper’s Review Bay Area Lawyers… Bear Fax B & G Black and White Men Together Black Leather...In Color Black Out Blau Blueboy Magazine Body Positive Bohemian Bugle Books To Watch Out For… Bon Vivant 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 Bottom Line Brat Attack Bravo Bridges The Bugle Bugle Magazine Bulk Male California Knight Life Capitol Hill Catalyst The Challenge Charis Chiron Rising Chrysalis Newsletter CLAGS Newsletter Color Life! Columns Northwest Coming Together CRIR Mandate CTC Quarterly Data Boy Dateline David Magazine De Janet Del Otro Lado Deneuve A Different Beat Different Light Review Directions for Gay Men Draghead Drummer Magazine Dungeon Master Ecce Queer Echo Eidophnsikon El Cuerpo Positivo Entre Nous Epicene ERA Magazine Ero Spirit Esto Etcetera 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 -

The Lived Experience of Monogamy Among Gay Men in Monogamous Relationships

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2020 The Lived Experience of Monogamy Among Gay Men in Monogamous Relationships Kellie L. Barton Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Clinical Psychology Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Social and Behavioral Sciences This is to certify that the doctoral dissertation by Kellie Barton has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Chet Lesniak, Committee Chairperson, Psychology Faculty Dr. Scott Friedman, Committee Member, Psychology Faculty Dr. Susan Marcus, University Reviewer, Psychology Faculty Chief Academic Officer and Provost Sue Subocz, Ph.D. Walden University 2020 Abstract The Lived Experience of Monogamy Among Gay Men in Monogamous Relationships by Kellie Barton MS, Walden University, 2012 BS, University of Phoenix, 2010 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Clinical Psychology Walden University February 2020 Abstract Research on male gay relationships spans more than 50 years, and the focus of most of this research has been on understanding the development processes, consequences, and risk factors of nonmonogamous relationships. Few researchers have explored the nature and meaning of monogamy in the male gay community. -

26891 HRC COVER.Indd

The Human Rights Campaign and the Human Rights Campaign Foundation / 2005 Annual Report / 25 Years of Progress / 2005 Annual Report 25 Years Human Rights Campaign and the Foundation The 1640 RHODE ISLAND AVENUE NW WASHINGTON, D.C. 20036-3278 TEL 202 628 4160 FAX 202 347 5323 2005 ANNUAL REPORT / 25 YEARS OF PROGRESS TTY 202 216 1572 WWW.HRC.ORG PR LIED INTI AL NG UNION R TRADES LABEL COUNCIL W 30 A S H I N G T O N TWENTY-FIVE YEARS OF PROGRESS. ABOVE: HUMAN RIGHTS CAMPAIGN FOUNDER STEVE ENDEAN 1980 (RIGHT) WITH VIC BASILE, THE FIRST EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR. Steve Endean establishes the Human Rights Campaign Fund, raising money for gay-supportive congressional candidates. LETTER FROM THE BOARD CO-CHAIRS Over the last year, the Human Rights Campaign and Human Rights Campaign Foundation family commemorated 25 years of working toward equality. In many ways, our work over the past year was emblematic of the progress we’ve made since 1980 and the challenges we still face. From stopping the Federal Marriage Amendment to making corporate America a fairer place, our staff worked tirelessly, logging countless hours on Capitol Hill, traveling thousands of miles to help in legislative battles on the state level, advocating in board rooms, reaching new supporters and informing reporters and editors across the country about the lives of gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender Americans. We also faced serious challenges in the states and on Capitol Hill, which served as an important reminder of the hard work ahead in educating the American people and of the importance of our enhanced investment in religion, coming out, workplace and family education projects. -

APPENDIX B Syphilis Case Illustrating the Application of the Manual APPENDIX B

APPENDIX B Syphilis Case Illustrating the Application of the Manual APPENDIX B Appendix B Syphilis Case Illustrating the Application of the Manual THE SITUATION After analyzing syphilis morbidity reports and interview records, STD officials in the city of Chancri-La noticed an increase in the number of syphilis cases among men who reported having sex with men (MSM). From 1999 to 2002, the number of MSM cases had gone up, as well as the percentage of MSM cases. In 1999, there was only 1 MSM case, which represented .9% of the syphilis cases in males. By 2002, the number of MSM cases had increased to 14, and represented 29.2% of their male cases. Further analysis revealed that the cases were not concentrated in one geographic part of the city, based on the males’ residences. However, through interviews conducted by the Disease Intervention Specialists (DIS), the STD officials learned that most of the males socialized in the same area. ACTIONS TAKEN A DIS was already screening sporadically at a gay bar. To address this emerging problem, STD officials initiated meetings with six community-based organizations (CBOs) that work with the MSM community. Together, they designed a plan of action to implement jointly. One of the activities implemented was syphilis screening in different venues (i.e., bathhouses, gay bars, CBOs, mobile unit, and a gay parade). The STD director and program staff were interested in determining which of these screening approaches was more successful in reaching the target population. The following illustrates the steps involved in designing and implementing this evaluation. -

LGBT History

LGBT History Just like any other marginalized group that has had to fight for acceptance and equal rights, the LGBT community has a history of events that have impacted the community. This is a collection of some of the major happenings in the LGBT community during the 20th century through today. It is broken up into three sections: Pre-Stonewall, Stonewall, and Post-Stonewall. This is because the move toward equality shifted dramatically after the Stonewall Riots. Please note this is not a comprehensive list. Pre-Stonewall 1913 Alfred Redl, head of Austrian Intelligence, committed suicide after being identified as a Russian double agent and a homosexual. His widely-published arrest gave birth to the notion that homosexuals are security risks. 1919 Magnus Hirschfeld founded the Institute for Sexology in Berlin. One of the primary focuses of this institute was civil rights for women and gay people. 1933 On January 30, Adolf Hitler banned the gay press in Germany. In that same year, Magnus Herschfeld’s Institute for Sexology was raided and over 12,000 books, periodicals, works of art and other materials were burned. Many of these items were completely irreplaceable. 1934 Gay people were beginning to be rounded up from German-occupied countries and sent to concentration camps. Just as Jews were made to wear the Star of David on the prison uniforms, gay people were required to wear a pink triangle. WWII Becomes a time of “great awakening” for queer people in the United States. The homosocial environments created by the military and number of women working outside the home provide greater opportunity for people to explore their sexuality. -

Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame 2001

CHICAGO GAY AND LESBIAN HALL OF FAME 2001 City of Chicago Commission on Human Relations Richard M. Daley Clarence N. Wood Mayor Chair/Commissioner Advisory Council on Gay and Lesbian Issues William W. Greaves Laura A. Rissover Director/Community Liaison Chairperson Ó 2001 Hall of Fame Committee. All rights reserved. COPIES OF THIS PUBLICATION ARE AVAILABLE UPON REQUEST City of Chicago Commission on Human Relations Advisory Council on Gay and Lesbian Issues 740 North Sedgwick Street, 3rd Floor Chicago, Illinois 60610 312.744.7911 (VOICE) 312.744.1088 (CTT/TDD) Www.GLHallofFame.org 1 2 3 CHICAGO GAY AND LESBIAN HALL OF FAME The Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame is both a historic event and an exhibit. Through the Hall of Fame, residents of Chicago and our country are made aware of the contributions of Chicago's lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered (LGBT) communities and the communities’ efforts to eradicate homophobic bias and discrimination. With the support of the City of Chicago Commission on Human Relations, the Advisory Council on Gay and Lesbian Issues established the Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame in June 1991. The inaugural induction ceremony took place during Pride Week at City Hall, hosted by Mayor Richard M. Daley. This was the first event of its kind in the country. The Hall of Fame recognizes the volunteer and professional achievements of people of the LGBT communities, their organizations, and their friends, as well as their contributions to their communities and to the city of Chicago. This is a unique tribute to dedicated individuals and organizations whose services have improved the quality of life for all of Chicago's citizens. -

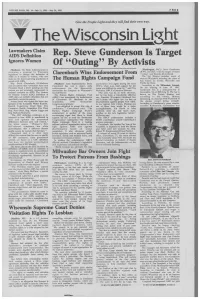

View Full Issue As

VOLUME FOUR, NO. 14—July 11, 1991—July 24, 1991 FREE Give the People Light and they will find their own way. The Wisconsin Light Lawmakers Claim AIDS Definition Rep. Steve Gunderson Is Target Ignores Women Of "Outing" By Activists [Madison]- The Bush Administration is [Washington, D.C.]- Steve Gunderson reviewing a proposal by Wisconsin (R-WI, 3rd Dist.) was the target of heavy legislators to change the definition of Clarenbach Wins Endorsement From "outing" over the July 4th weekend. AIDS as it relates to women, who now The 3rd District includes much of make up the fastest-growing population of The Human Rights Campaign Fund western Wisconsin including the cities of people with AIDS. Eau Claire, La Crosse, Platteville and Rep. David Clarenbach (D-Madison) [Madison]. State Representative David and Lesbian civil rights during the early Prairie du Chien. and seventeen other lawmakers have sent Clarenbach has won a major, early 1970's, when even mild support for the According to the Milwaukee Journal, President Bush a letter pointing out that endorsement for the Democratic cause was difficult to come by," said Tim On the evening of June 30, 1991, woman are not accurately represented in nomination for Congress in Wisconsin's McFeeley, HRCF's Executive Director. Gunderson was in a restaurant/bar in national statistics on AIDS. The Centers Second District. "Not only was he an early advocate, Alexandria, VA at 808 King St. The bar is for Disease Control (CDC) definition of The Human Rights Campaign Fund but he has been a remarkable effective known as The French Quarter and AIDS does not include infections that are (HRCF) has announced its endorsement one.