A Scientific Review of Abstinence and Abstinence Programs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SEX (Education)

A Guide to Eective Programming for Muslim Youth LET’S TALK ABOUT SEX (education) A Resource Developed by the HEART Peers Program i A Guide to Sexual Health Education for Muslim Youth AT THE heart of the CENTRAL TO ALL MATTER WORKSHOPS WAS THE HEART Women & Girls seeks to promote the reproductive FOLLOWING QUESTION: health and mental well-being of faith-based communities through culturally-sensitive health education. How can we convey information about sexual Acknowledgments About the Project and reproductive health This toolkit is the culmination of three years of research The inaugural peer health education program, HEART and fieldwork led by HEART Women & Girls, an Peers, brought together eight dynamic college-aged to American Muslim organization committed to giving Muslim women and Muslim women from Loyola University, the University girls a safe platform to discuss sensitive topics such as of Chicago, and the University of Wisconsin–Madison women and girls in a body image, reproductive health, and self-esteem. The for a twelve-session training on sexual and reproductive final toolkit was prepared by HEART’s Executive Director health, with a special focus on sexual violence. Our eight manner that is mindful Nadiah Mohajir, with significant contributions from peer educator trainees comprised a diverse group with of religious and cultural Ayesha Akhtar, HEART co-founder & former Policy and respect to ethnicity, religious upbringing and practice, Research Director, and eight dynamic Muslim college- and professional training. Yet they all came together values and attitudes aged women trained as sexual health peer educators. for one purpose: to learn how to serve as resources for We extend special thanks to each of our eight educators, their Muslim peers regarding sexual and reproductive and also advocates the Yasmeen Shaban, Sarah Hasan, Aayah Fatayerji, Hadia health. -

Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Monasteries

Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Monasteries Atlas of Whether used as a scholarly introduction into Eastern Christian monasticism or researcher’s directory or a travel guide, Alexei Krindatch brings together a fascinating collection of articles, facts, and statistics to comprehensively describe Orthodox Christian Monasteries in the United States. The careful examina- Atlas of American Orthodox tion of the key features of Orthodox monasteries provides solid academic frame for this book. With enticing verbal and photographic renderings, twenty-three Orthodox monastic communities scattered throughout the United States are brought to life for the reader. This is an essential book for anyone seeking to sample, explore or just better understand Orthodox Christian monastic life. Christian Monasteries Scott Thumma, Ph.D. Director Hartford Institute for Religion Research A truly delightful insight into Orthodox monasticism in the United States. The chapters on the history and tradition of Orthodox monasticism are carefully written to provide the reader with a solid theological understanding. They are then followed by a very human and personal description of the individual US Orthodox monasteries. A good resource for scholars, but also an excellent ‘tour guide’ for those seeking a more personal and intimate experience of monasticism. Thomas Gaunt, S.J., Ph.D. Executive Director Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA) This is a fascinating and comprehensive guide to a small but important sector of American religious life. Whether you want to know about the history and theology of Orthodox monasticism or you just want to know what to expect if you visit, the stories, maps, and directories here are invaluable. -

After the Wedding Night: the Confluence of Masculinity and Purity in Married Life Sarah H. Diefendorf a Thesis Submitted in Part

After the Wedding Night: The Confluence of Masculinity and Purity in Married Life Sarah H. Diefendorf A thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Washington 2012 Committee: Pepper Schwartz Julie Brines Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Department of Sociology University of Washington Abstract After the Wedding Night: The Confluence of Masculinity and Purity in Married Life Sarah H. Diefendorf Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Pepper Schwartz Department of Sociology Purity is congruent with cultural understandings of femininity, but incongruent with normative definitions of masculinity. Using longitudinal qualitative data, this study analyzes interviews with men who have taken pledges of abstinence pre and post marriage, to better understand the ways in which masculinity is asserted within discourses of purity. Building off of Wilkins’ concept of collective performances of temptation and Luker’s theoretical framing of the “sexual conservative” I argue that repercussions from collective performances of temptation carry over into married life; sex is thought of as something that needs to be controlled both pre and post marriage. Second, because of these repercussions, marriage needs to be re-conceptualized as a “verb”; marriage is not a static event for sexual liberals or sexual conservatives. The current study highlights the ways in which married life is affected by a pledge of abstinence and contributes to the theoretical framing of masculinities as fluid. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to thank Pepper Schwartz and Julie Brines for their pointed feedback and consistent encouragement and enthusiasm for this research. The author would also like to thank both Aimée Dechter and the participants of the 2011-2012 Masters Thesis Research Seminar for providing the space for many lively, helpful discussions about this work. -

7Th Grade 3.06 Define Abstinence As Voluntarily Refraining from Intimate

North Carolina Comprehensive School Health Training Center 3/07 C. 7th grade 3.06 Define abstinence as voluntarily refraining from intimate sexual contact that could result in unintended pregnancy or disease and analyze the benefits of abstinence from sexual until marriage. 7th grade 3.08 Analyze the effectiveness and failure rates of condoms as a means of preventing sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV/AIDS. 8th grade 3.08 Compare and contrast methods of contraception, their effectiveness and failure rates, and the risks associated with different methods of contraception, as a means of preventing sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV/AIDS. Materials Needed: Appendix 1 – Conception Quiz/STD Quiz – Teacher’s Key desk bells Appendix 2 – transparency of quotes about risk taking Appendix 3 – transparency of Effectiveness Rates for Contraceptive Methods Appendix 4 – background information on condom efficacy Appendix 5 – signs and cards for Contraceptive Effectiveness (cut apart) Appendix 6 – copies of What Would You Say? Review: Ask eight students to come to the front of the room and form two teams of four. They are to line up so they can ring in to answer questions using the Conception Quiz – Teacher’s Key for Appendix 1. Assign another student to determine who rings in first and explain they cannot ring in until they have heard the entire question. Each student will answer a question, go to the end of the line, and then have a second turn answering a question. If the question can be answered “yes” or “no,” they are to explain “why” or “why not.” Ask another eight students to come to the front and repeat the activity using the STD Quiz – Teacher’s Key. -

Abstinence Education in Context: History, Evidence, Premises, and Comparison to Comprehensive Sexuality Education

IN MAUREEN KENNY (ED.) (2014). SEX EDUCATION. HAUPPAUGE, NY: NOVA SCIENCE PUBLISHERS. WWW.NOVAPUBLISHERS.COM ABSTINENCE EDUCATION IN CONTEXT: HISTORY, EVIDENCE, PREMISES, AND COMPARISON TO COMPREHENSIVE SEXUALITY EDUCATION Stan E. Weed, Ph.D. The Institute for Research and Evaluation Thomas Lickona, Ph.D. Center for the 4th and 5th Rs (Respect and Responsibility) School of Education, State University of New York at Cortland ABSTRACT This chapter provides a broad picture of the abstinence education movement in the U.S. and the historical, political, and theoretical context of its journey. It describes the problems it has targeted, the policies and programs it has designed to solve them, and the results of these various interventions. Solutions to the problems posed by adolescent sexual activity have fallen into three camps: risk reduction, risk avoidance, and a combination of those two approaches. This historical context permits a comparative analysis of the most common sex education strategies and provides a better understanding of what abstinence education actually looks like—what it is and what it is not. In addition to describing the outcomes of the different approaches to sex education, we examine their foundational premises and assumptions, with the intent to clarify not only what does or does not work but also the reasons for success or failure. As important as the effectiveness question is, the underlying rationale, theory, or premise on which any program strategy is based is equally important if we are to understand how to benefit from prior successes and failures. In addressing these issues, we propose and describe an empirical model that delineates key predictors of adolescent risk behavior and demonstrates important causal mechanisms that program developers can focus on for more effective interventions. -

Benefits of Sexual Expression

White Paper Published by the Katharine Dexter McCormick Library Planned Parenthood Federation of America 434 W est 33rd Street New York, NY 10001 212-261-4779 www.plannedparenthood.org www.teenwire.com Current as of July 2007 The Health Benefits of Sexual Expression Published in Cooperation with the Society for the Scientific Study of Sexuality In 1994, the 14th World Congress of Sexology with the vast sexological literature on dysfunction, adopted the Declaration of Sexual Rights. This disease, and unwanted pregnancy, we are document of “fundamental and universal human accumulating data to begin to answer many rights” included the right to sexual pleasure. This questions about the potential benefits of sexual international gathering of sexuality scientists expression, including declared, “Sexual pleasure, including autoeroticism, • What are the ways in which sexual is a source of physical, psychological, intellectual expression benefits us physically? and spiritual well-being” (WAS, 1994). • How do various forms of sexual expression benefit us emotionally? Despite this scientific view, the belief that sex has a • Are there connections between sexual negative effect upon the individual has been more activity and spirituality? common in many historical and most contemporary • Are there positive ways that early sex play cultures. In fact, Western civilization has a affects personal growth? millennia-long tradition of sex-negative attitudes and • How does sexual expression positively biases. In the United States, this heritage was affect the lives of the disabled? relieved briefly by the “joy-of-sex” revolution of the • How does sexual expression positively ‘60s and ‘70s, but alarmist sexual viewpoints affect the lives of older women and men? retrenched and solidified with the advent of the HIV • Do non-procreative sexual activities have pandemic. -

LESSON 1 Isti'faf (Abstinence) 1. Explain the Concept of Isti'faf: Ans

LESSON 1 Isti’faf (Abstinence) 1. Explain the concept of Isti’faf: Ans : Isti'faf or abstinence means to seek modesty and honesty. Abstinence means to abstain from improper behavior and all that is contrary to sense of honor and good character. 2. The importance and effects of abstinence: First: The effects of istifaf (abstinence) on individuals: 1. Higher ambition, keeping away from unimportant matters and involvement in useful things, like seeking knowledge and searching for solutions to scientific, social or humanitarian issues. Thus, man develops higher goals and endeavors which he seeks to achieve. 2. Assuming communal responsibility, for abstinence prevents Muslims from harming others. This enables an individual to conduct his duty toward his community by keeping and defending his interests and extending benefits to all creatures. 3. Winning the trust, respect and love of others. Allah, glory be to Him, says: “The good deed and the evil deed are not alike. Repel (the evil deed) with one which is better, then lo! He, between whom and you there was enmity (will become) as though he was a bosom friend." (Surat Fussilat) Second: The effect of abstinence on society:: 1. The solidarity of society against dangers as a result of confidence among its members. 2. Freedom of society from crime because its members bear their societal responsibilities. 3. The progress and prosperity of the community as a result of diligence and high aspirations of its members. 4. Stable financial and economic dealings and exchange of benefits and interests, which strengthens the economic security of society. 3. What are the two areas of ísti’faf’ the holy verses focus on? Explain. -

The Collapse of Ascetical Discipline and Clerical Misconduct: Sex and Prayer

The Linacre Quarterly Volume 73 | Number 1 Article 1 February 2006 The olC lapse of Ascetical Discipline And Clerical Misconduct: Sex and Prayer: A Reflection on the Relationship Between the Lack of Asceticism and Sex Abuse Richard Cross Daniel Thoma Follow this and additional works at: http://epublications.marquette.edu/lnq Recommended Citation Cross, Richard and Thoma, Daniel (2006) "The oC llapse of Ascetical Discipline And Clerical Misconduct: Sex and Prayer: A Reflection on the Relationship Between the Lack of Asceticism and Sex Abuse," The Linacre Quarterly: Vol. 73 : No. 1 , Article 1. Available at: http://epublications.marquette.edu/lnq/vol73/iss1/1 The Collapse of Ascetical Discipline And Clerical Misconduct: Sex and Prayer by Richard Cross, Ph.D., (With research data from Daniel Thoma, Ph.D.) A Reflection on the Relationship Between the Lack ofAsceticism and Sex Abuse Sponsored by the Linacre Institute and The Catholic Physicians' Guild of Chicago Preface The Linacre Institute and the Chicago Catholic Physicians' Guild commissioned this analysis of the priest abuse crisis became we feel that the National Review Board and the John Jay Reports, valuablt! as they are, do not uncover the fundamental cause of the scandal nor do they make suggestions to correct that cause. This short forward willi) note the NCCB efforts to define the scandal but without really discussing the basic cause, which was an absence of priestly asceticism; 2) define the role of asceticism as essential to obtain holiness in priestly formation and, 3) briefly summarize this book's content. The priest sex abuse scandal, since it first received national media attention in Boston in 2002, has been a major source of concern for the American Catholic Church. -

Abuse, Celibacy, Catholic, Church, Priest

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences 2012, 2(4): 88-93 DOI: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20120204.03 The Psychology Behind Celibacy Kas o mo Danie l Maseno University in Kenya, Department of Religion Theology and Philosophy Abstract Celibacy began in the early church as an ascetic discipline, rooted partly in a neo-Platonic contempt for the physical world that had nothing to do with the Gospel. The renunciation of sexual expression by men fit nicely with a patriarchal denigration of women. Non virginal women, typified by Eve as the temptress of Adam, were seen as a source of sin. In Scripture: Jesus said to the Pharisees, “And I say to you, whoever divorces his wife, except for unchastity, and marries another commits adultery.” His disciples said to him, “If such is the case of a man with his wife, it is better not to marry.” But he said to them, “Not everyone can accept this teaching, but only those to whom it is given. For there are eunuchs who have been so from birth, there are eunuchs who have been made eunuchs by others, and there are eunuchs who have made themselves eunuchs for the sake of the kingdom of heaven. Let anyone accept this who can.” (Matthew 19:3-12).Jesus Advocates for optional celibacy. For nearly 2000 years the Catholic Church has proclaimed Church laws and doctrines intended to more clearly explain the teachings of Christ. But remarkably, while history reveals that Jesus selected only married men to serve as His apostles, the Church today forbids priestly marriage. -

The Addictive Potential of Sexual Behavior (Impulse) Review2

Page 1 of 9 Impulse: The Premier Journal for Undergraduate Publications in the Neurosciences Submitted for Publication January, 2018 The Addictive Potential of Sexual Behavior Heather Bool D’Youville College, Buffalo, New York This paper examines the addictive potential of sexual behavior through behavioral and neurophysiological mechanisms analogous to other formalized addictions. Sexual behavior refers to any action or thought preformed with the intention of sexual gratification, such as the consumption of explicit material, masturbation, fantasizing of sexual scenarios, and sexual intercourse. Addiction is defined by the presence of tolerance, preoccupation, withdrawal, dependence, and the continuation of behavior despite risk and/or harm. Sexual addiction demonstrates high relapse potential due to the frequency of reward-associated cues encountered in daily life, and the low effort and risk required for sexual pleasure. Currently, sexual addiction lacks a formal diagnosis despite behavioral, psychological, and physiological evidence. An official diagnosis recognized by a governing authority, such as the American Psychological Association, would offer greater access to treatment, funding for research, and exposure and education for the general public about this disorder. Abbreviations: None Keywords: Sexual Behavior; Addiction; Sexual Addiction; Neurophysiology; Behavioral Neuroscience Introduction “Sexual addiction” is an umbrella term Confusion remains regarding the for sexual impulsivity, sexual compulsivity, out- etiology and nosology of sexual addiction, of-control sexual behavior, hypersexual which has led to the lack of a universally behavior or disorder, sexually excessive accepted criterion and, more importantly, the behavior or disorder, Don Jaunism, satyriasis, absence of a formal diagnosis. A lack of and obsessive-compulsive sexual behavior operationalization of the disorder has severe (Beech et al., 2009; Karila et al., 2014; effects on research; due to the use of Rosenberg et al., 2014). -

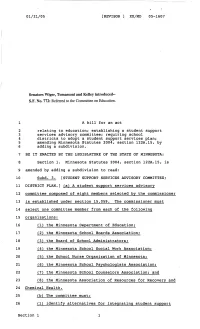

1 a Bill for an .Act 05-1607 2 Relating to Education

01/21/05 [REVISOR ] XX/MD 05-1607 Senators Wiger, Tomassoni and Kelley introduced- S.F. No. 772: Referred to the Committee on Education. 1 A bill for an .act 2 relating to education; establishing a student support 3 services advisory committee; requiring school 4 districts to adopt a student support services plan; 5 amending Minnesota Statutes 2004, section 122A.15, by 6 adding a subdivision. 7 BE IT ENACTED BY THE LEGISLATURE OF THE STATE OF MINNESOTA: 8 Section 1. Minnesota Statutes 2004, section 122A.15, is 9 amended by adding a subdivision to read: 10 Subd. 3. [STUDENT SUPPORT SERVICES ADVISORY COMMITTEE; 11 DISTRICT PLAN.] (a) A student support services advisory 12 committee composed of eight members selected by .the commissioner 13 is established under section 15.059. The commissioner must 14 select one committee member from each of the following 15 organizations: 16 (1) the Minnesota Department of Education; 17 (2) the Minnesota School Boards Association; 18 (3) the Board of School Administrators; 19 (4) the Minnesota School Social Work Association; 20 (5) the School Nurse Organization of Minnesota; 21 (6) the Minnesota School Psychologists Association; 22 (7) the Minnesota School Counselors Association; and 23 (8) the Minnesota Association of Resources for Recovery and 24 Chemical Health. 25 (b) The committee must: 26 (1) identify alternatives for integrating student support Section 1 1 01/21/05 [REVISOR ] XX/MD 05-1607 1 services into public schools; 2 (2) recommend support staff to student ratios and best 3 practices for providing student support services premised on 4 valid, widely recognized research; 5 (3) identify the substance and extent of the work that 6 . -

CROSSLING, LOVE L., Ph.D. Abstinence Curriculum in Black Churches: a Critical Examination of the Intersectionality of Race, Gender, and SES

CROSSLING, LOVE L., Ph.D. Abstinence Curriculum in Black Churches: A Critical Examination of the Intersectionality of Race, Gender, and SES. (2009) Directed by Dr. Kathleen Casey. 243 pp. Current sex education curriculum focuses on pregnancy and disease, but very little of the curriculum addresses the social, emotional, or moral elements. Christian churches have made strides over the last two decades to design an abstinence curriculum that contains a moral strand, which addresses spiritual, mental, social, and emotional challenges of premarital sex for youth and singles. However, many black churches appear to be challenged in four areas: existence, purpose, developmental process, and content of teaching tools at it relates to abstinence curriculum. Existence refers to whether or not a church body deems it necessary or has the available resources to implement an abstinence curriculum. Purpose refers to the overall goals and motivations used to persuade youth and singles. Developmental process describes communicative power dynamics that influence the recognized voices at the decision-making table when designing a curriculum. Finally, content of teaching tools refers to prevailing white middle class messages found in Christian inspirational abstinence texts whose cultural irrelevance creates a barrier in what should be a relevant message for any population. The first component of the research answers the question of why the focus should be black churches by exploring historical and contemporary distinctions of black sexuality among youth and single populations. The historical and contemporary distinctions are followed by an exploration of how the history of black church development influenced power dynamics, which in turn affects the freedom with which black Christian communities communicate about sexuality in the church setting.