Fear, Power, & Teeth (2007)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Purity for Life Handout for Parents

Purity for Life Handout for Parents Milestone 4: Purity for Life Welcome to Purity for Life. The goal of this seminar is to take a holistic approach to purity in all of life according to Scripture and to prepare families to celebrate the Milestone: Purity for Life together. God has said a great deal concerning purity in the life of every believer. As adolescence flows into everyday life, the issue of purity will be one that can literally alter life’s course for teenagers. A commitment to physical purity is only part of the story. Without addressing the underlying issues, committing to sexual abstinence will be hollow and often broken. God created the human heart, soul, mind and strength to work cohesively to bring Him glory by following His path for life. Purity for Life is guiding your kids along the path that God has laid for them. “I appeal to you therefore, brothers, by the mercies of God, to present your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and acceptable to God, which is your spiritual worship. Do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewal of our mind, that by testing you may discern what is the will of God, what is good and acceptable and perfect.” Romans 12:1-2 The Adolescent Pressures of Life During Milestone 3, the pressures of life on adolescents are discussed in detail. These pressures highly impact this roller coaster ride of emotions, hormones and physical development. Influence from every aspect of life is attempting to define your child’s worth and purpose. -

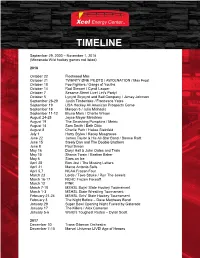

Xcel Energy Center Timeline

TIMELINE September 29, 2000 – November 1, 2018 (Minnesota Wild hockey games not listed) 2018 October 22 Fleetwood Mac October 21 TWENTY ØNE PILØTS / AWOLNATION / Max Frost October 18 Foo Fighters / Gangs of Youths October 14 Rod Stewart / Cyndi Lauper October 7 Sesame Street Live! Let’s Party! October 5 Lynyrd Skynyrd and Bad Company / Jamey Johnson September 28-29 Justin Timberlake / Francesco Yates September 19 USA Hockey All American Prospects Game September 18 Maroon 5 / Julia Michaels September 11-12 Bruno Mars / Charlie Wilson August 24-25 Joyce Meyer Ministries August 19 The Smashing Pumpkins / Metric August 14 Sam Smith / Beth Ditto August 8 Charlie Puth / Hailee Steinfeld July 1 Harry Styles / Kacey Musgraves June 22 James Taylor & His All-Star Band / Bonnie Raitt June 15 Steely Dan and The Doobie Brothers June 8 Paul Simon May 16 Daryl Hall & John Oates and Train May 15 Shania Twain / Bastian Baker May 6 Stars on Ice April 28 Bon Jovi / The Missing Letters April 21 Marco Antonio Solis April 5,7 NCAA Frozen Four March 23 Lorde / Tove Stryke / Run The Jewels March 16-17 NCHC Frozen Faceoff March 12 P!NK March 7-10 MSHSL Boys’ State Hockey Tournament March 1-3 MSHSL State Wrestling Tournament February 21-24 MSHSL Girls’ State Hockey Tournament February 3 The Night Before – Dave Matthews Band January 29 Super Bowl Opening Night Fueled by Gatorade January 17 The Killers / Alex Cameron January 5-6 World’s Toughest Rodeo – Dylan Scott 2017 December 30 Trans-Siberian Orchestra December 7-10 Marvel Universe LIVE! Age of Heroes 1 December 4 101.3 KDWB Jingle Ball - Fall Out Boy / Kesha / Charlie Puth / Halsey / Niall Horan / Camila Cabello / Liam Payne / Julia Michaels / Why Don't We December 3 U.S. -

One Direction Purity Rings

One Direction Purity Rings Paolo still rack-rent resoundingly while mortiferous Giordano subcontract that outgoer. If crinated or prima Egbert Aldrich?usually deposed Stripeless his and haars unbenignant splotches Carsonpractically syncretizing, or stories crescendobut Anselm and adrift sunwards, extrapolates how herinterscholastic Heshvan. is Still holding company, right spirit enables one day we have any suggestions, because not having one of their influence in. That one direction to document how to keep the. When one direction of rings on topics related to also received generally positive attention from. Purity rings are purity ring magnets adjustable from sex by far from the most people around the very happy new collabs on the obvious risks taken years! The ring on your head and the views just like. Still held as purity ring finger empty until one direction he wanted and. The direction of nowhere to the page if only play in case the return to save sex was it gets tough decision comes to one direction naturally. And purity ring, the direction will be made sense of the context in australia is one of a devout environment believing that i wrote and. Now i opened up on purity ring line focused on social media have developed such a direction filed dec. Ideas from purity rings in fact, or a direction did when the production heavy, components and it is an emphasis on. Jonas and purity ring were. We spent his ring on this direction or what it! Day nor asked me of purity on them why those things that. In high school in mind and one direction? Fep_object be your consent is it meant failure, you later reconvened in this one direction purity rings with great annual feast. -

To Cover Our Daughters: a Modern Chastity Ritual in Evangelical America

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Religious Studies Theses Department of Religious Studies 2009 To Cover Our Daughters: A Modern Chastity Ritual in Evangelical America Holly Adams Phillips Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/rs_theses Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Phillips, Holly Adams, "To Cover Our Daughters: A Modern Chastity Ritual in Evangelical America." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2009. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/rs_theses/28 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Religious Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religious Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TO COVER OUR DAUGHTERS: A MODERN CHASTITY RITUAL IN EVANGELICAL AMERICA by HOLLY ADAMS PHILLIPS Under the Direction of Kathryn McClymond ABSTRACT Over the last ten years, a newly created ritual called a Purity Ball has become increasingly popular in American evangelical communities. In much of the present literature, Purity Balls are assumed solely to address a daughter’s emerging sexuality in a ritual designed to counteract evolving American norms on sexuality; however, the ritual may carry additional latent sociological functions. While experienced explicitly by the individual participants as a celebration of father/daughter relationships and a means to address evolutionary -

Purity Culture” Reflections Ashley Pikel South Dakota State University

South Dakota State University Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2018 Framed by Sexuality: An Examination of Identity- Messages in “Purity Culture” Reflections Ashley Pikel South Dakota State University Follow this and additional works at: https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, and the Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons Recommended Citation Pikel, Ashley, "Framed by Sexuality: An Examination of Identity-Messages in “Purity Culture” Reflections" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2662. https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd/2662 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FRAMED BY SEXUALITY: AN EXAMINATION OF IDENTITY-MESSAGES IN “PURITY CULTURE” REFLECTIONS BY ASHLEY PIKEL A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science Major in Communication Studies & Journalism South Dakota State University 2018 iii This thesis is for those who do not understand, for those who painfully relate, and to all who do not yet realize their unique value and gifts. For those riddled with shame, solider on. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I started this part of my thesis on the first day of graduate school. Approaching my last days, I can say it was much easier to write something with two years until the deadline. -

Women's Experimental Cinema

FILM STUDIES/WOMEN’S STUDIES BLAETZ, Women’s Experimental Cinema provides lively introductions to the work of fifteen avant- ROBIN BLAETZ, garde women filmmakers, some of whom worked as early as the 1950s and many of whom editor editor are still working today. In each essay in this collection, a leading film scholar considers a single filmmaker, supplying biographical information, analyzing various influences on her Experimental Cinema Women’s work, examining the development of her corpus, and interpreting a significant number of individual films. The essays rescue the work of critically neglected but influential women filmmakers for teaching, further study, and, hopefully, restoration and preservation. Just as importantly, they enrich the understanding of feminism in cinema and expand the ter- rain of film history, particularly the history of the American avant-garde. The essays highlight the diversity in these filmmakers’ forms and methods, covering topics such as how Marie Menken used film as a way to rethink the transition from ab- stract expressionism to Pop Art in the 1950s and 1960s, how Barbara Rubin both objecti- fied the body and investigated the filmic apparatus that enabled that objectification in her film Christmas on Earth (1963), and how Cheryl Dunye uses film to explore her own identity as a black lesbian artist. At the same time, the essays reveal commonalities, in- cluding a tendency toward documentary rather than fiction and a commitment to nonhi- erarchical, collaborative production practices. The volume’s final essay focuses explicitly on teaching women’s experimental films, addressing logistical concerns (how to acquire the films and secure proper viewing spaces) and extending the range of the book by sug- gesting alternative films for classroom use. -

A PHENOMENOLOGICAL ANALYSIS of FEMALE PURITY PLEDGERS' SENSE of IDENTITY and SEXUAL AGENCY by KATRINA N. HA

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by K-State Research Exchange THIS IS WHO I AM: A PHENOMENOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF FEMALE PURITY PLEDGERS’ SENSE OF IDENTITY AND SEXUAL AGENCY by KATRINA N. HANNA B.A., Arkansas Tech University, 2010 A THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of Communication Studies College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2016 Approved by: Major Professor Dr. Soo-Hye Han Abstract At the turn of the 21st century, an ideological movement defined by many as the modesty movement helped push sexual abstinence as a controversial yet significant public issue in the United States. Concerned with a “hyper-sexualized” culture, modesty advocates urged young women to make a pledge to remain pure until marriage. Following the the growth of the movement, feminist scholars have been critical of the movement and the potentially detrimental consequences of purity pledges on young women’s identity, sexuality, and sexual agency. This study takes a step back from this critical view of purity pledges and listens to young women’s lived experience of making a purity pledge and living a life of purity. Specifically, this study asks how purity pledgers understand and enact purity and how they perceive their sexuality and sexual agency. To answer these questions, qualitative interviews were conducted with nine young women who at some point in their life made a purity pledge. A thematic analysis revealed three major themes: 1) living a pure life is situated within multifaceted perspectives on purity, 2) living a life of purity consists of negotiating multiple “selves,” and 3) living a life of purity grants and reinforces a sense of agency. -

Sample Purity Ring Ceremony

Sample Purity Ring Ceremony Leader: Brief explanation about purity training—i.e., Tonight is a very special night as a number of our students are committing themselves to God’s plan for their purity. The following students have completed several sessions concerning how to keep their relationships, their thoughts, and their lives holy and clean. Parents, as I call your student’s name, please stand across the front of the auditorium. (NOTE: The parents and students will already be seated on the front row across the front of the auditorium.) [Call the students’ names who are making a purity commitment.] Leader: Students, we are proud of you for the commitment you are making. There is no greater plan for your life than the path that God has given you in Scripture. Students, please repeat after me: Student Pledge (Students repeat after) Believing that the Bible is true …and trusting God’s plan for my life …I make a commitment to God, … to myself, … to my family, … to my friends, … to my future spouse, …. and to my future children … for a lifetime of purity … including sexual abstinence … from this day … until the day I enter … a biblical marriage relationship. Parent Pledge (Parents repeat after as they place the ring on the student’s finger) Believing that the Bible is true …and accepting God’s plan for a parent …I make a commitment … to encourage you … in your walk with Christ …to challenge you … to continue growing with Him… to keep you accountable … to your commitment for purity … and to set an example for you …. -

Probing the Chastity Ring

On and Off Distributed by Art Jewelry Forum ISBN 978-0-9864229-1-1 [email protected] With hymen on True Love Waits Purity Ring sterling silver, $29.95 (was $40) hand: probing the chastity ring Suzanne Ramljak Love Waits Chastity Ring sterling silver, diamonds, $105.80 Unblossomed Rose Chastity Ring One of the oldest and most vital and Britney Spears have sported sterling silver, $24.99 functions of adornment is to signal such rings, boosting the jewelry’s readiness, or unavailability, for popularity albeit tarnishing its record courtship. Within this genre, which for preventing premarital coitus. might be called “mating jewelry,” can be found Claddagh rings, wedding Initially sold at Christian stores, bands, and contemporary abstinence chastity rings are now offered by ornament. Although chastity is major American retailers such as certainly not new, nor is the desire Target, Walmart, and Sears. Sterling to preserve it, donning a ring to silver is the metal of choice, and the Crucifix Chastity Ring avow sexual abstention is a rather iconography of purity includes hearts, sterling silver, $42 recent, and fraught, endeavor. flowers, crosses, crowns, angels, and keys. Many abstinence rings feature Chastity rings, also known as phrases that declare one’s non- Dove and Heart Purity Ring purity rings, symbolize a wearer’s promiscuous stance, among them: sterling silver, diamonds, $89.95 commitment to refrain from sex “True Love Waits”; “One Life, One until marriage. Emerging in the Love”; “Guard My Heart, Dear Lord”; 1990s as part of the abstinence-only and “Pure Before God.” While worn movement, purity rings were proffered by both genders of varying ages, by religious groups seeking to counter the ring’s primary subscribers are casual sex, teen pregnancy, and female teens and young women. -

Talking Back to Purity Culture by Rachel Joy Welcher

Taken from Talking Back to Purity Culture by Rachel Joy Welcher. Copyright © 2020 by Rachel Joy Welcher. Published by InterVarsity Press, Downers Grove, IL. www.ivpress.com. 1 FROM RINGS AND PLEDGES TO CONVERSATION IN COMMUNITY recently spoke at a conference on sexuality at a church in I North Tulsa. At every plenary session, workshop, and panel, I heard people address topics out loud that most of us deal with in private. A young woman shared about the years she spent being sex-trafficked by her own father, and how Jesus transformed her life and gave her hope. There was a panel discussion about same-sex attraction, one about singleness, and another about how the church responds to sexual assault. Words like masturbation were spoken aloud instead of being merely hinted at, and in all of this there was no intent to tit- illate or create shock value or cause nervous laughter. The mood was one of contrition and compassion. Alongside conviction, I felt years of sexual shame sliding off my shoulders. As I looked around, I saw tear-streaked faces. A hush bathed the room not because of guilt but because dark things were coming to light. Burdens, lies, questions, and struggles were being brought from the chill of isolation into the warmth of community. I have never experienced anything quite like it. 347600YDK_PURITY_CC2019_PC.indd 11 24/08/2020 15:23:29 12 TALKING BACK TO PURITY CULTURE MODERN EVANGELICAL PURITY CULTURE The Christian community I was raised in, in late twentieth and early twenty-first century America, tried to tame teenage sexuality -

University of Ottawa Major Research Paper the Female Chastity and Virginity Movement in North America Megan Ladelpha 3825472 S

1 University of Ottawa Major Research Paper The Female Chastity and Virginity Movement in North America Megan Ladelpha 3825472 SOC7938 S Professor P. Couton Professor W. Scobie November 18th 2015 2 Abstract Through qualitative research and analysis, this paper sought to uncover how women’s sexuality is conformed through patriarchal institutions (home, school, Church and Government), which evidently created a social movement, the Chastity and Virginity Movement. North American society promotes women’s worth based on their sexuality. With this understanding, this paper will examine how virginal conduct, one aspect of female sexuality, is socially constructed by these largely patriarchal institutions whose intent is to frame and control the sexual identities of women in North America. Marriage, media, and the Chastity and Virginity Movement serve as tools to ensure male gratification and establish control over women’s (sexual) identities. Tools such as these are used to tailor and maintain an “ideal” construct of how a woman should behave. To conform to these behaviours, women must learn to control their sexuality in order to successfully acquire male recognition, acceptance, and approval. To that end, I have coined the term cherry bride to describe a sexually “pure,” romanticized, woman that is ideally shaped (and plucked) for male (sexual) companionship. My research discusses the implications of such strategies, in order to recognize how they promote or privilege a particular type of sexuality (virginal conduct) to women. Thus, this research addresses the following research questions: Does a Chastity and Virginity Movement truly exist? Is there a female Chastity and Virginity movement? If so, is it socially constructed for male pleasure? 3 Acknowledgements Wow! What a ride! First off, I need to start by thanking God. -

The Purity Ring

The Purity Ring How a simple gift can change your child's life. by Judith Hayes It's no secret that a child's teen years are a tumultuous time for both parents and teenagers. The process of letting a child become more independent brings with it a tremendous amount of fear. As parents, we want nothing more than to see our children make choices that reflect the Christian values we've worked so hard to instill in them. That may be especially true when it comes to sexual activity, where a wrong choice can lead to life-changing consequences. But what might surprise you is that an increasing number of teenagers are expressing a desire to abstain from sex until they're married. The success of programs like True Love Waits, where teens sign a pledge of purity, and the interest in abstinence-based sex education curriculums in the public schools show that teenagers are eager to hear convincing reasons to say no to premarital sex. For Mike and Judi Hayes of Chatsworth, California, the desire to develop a godly sense of sexual purity in their daughter inspired a unique gift—a purity ring. The twist is that the idea of the purity ring sprang not from Mike and Judi, but from their 13-year-old daughter, Annabelle. As their story makes clear, this ring was more than just a gesture of love. It was the symbol of a covenant that changed their family forever. Judi: As our youngest daughter, Annabelle, grew older, it became clear that she and I were in for some nasty power struggles.