Faith, Virginity, and Shame in the Evangelical Purity Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fear, Power, & Teeth (2007)

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Graduate School Professional Papers 2019 Fear, Power, & Teeth (2007) Olivia Hockenbroch Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Social Influence and Political Communication Commons, Speech and Rhetorical Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hockenbroch, Olivia, "Fear, Power, & Teeth (2007)" (2019). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 11326. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/11326 This Professional Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running Head: FEAR, POWER, AND TEETH (2007) FEAR, POWER, & TEETH (2007) By OLIVIA ANNE HOCKENBROCH Communication with Philosophy Bachelor of Arts Juniata College, Huntingdon, PA 2015 Professional Paper Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In Communication Studies, Rhetoric & Public Discourse The University of Montana Missoula, MT May 2019 Approved by: Dr. Greg Larson, Chair Department of Communication Studies Dr. Sara Hayden, Advisor Department of Communication Studies Dr. Betsy BacH Department of Communication Studies Dr. Kathleen Kane Department of English FEAR, POWER, AND TEETH (2007) 1 Fear, Power, and Teeth (2007) Literature Review Vagina dentata is the myth of the toothed vagina; in most iterations, it serves as a warning to men that women’s vaginas must be conquered to be safe for a man’s sexual pleasure (Koehler, 2017). -

Praise & Worship from Moody Radio

Praise & Worship from Moody Radio 04/28/15 Tuesday 12 A (CT) Air Time (CT) Title Artist Album 12:00:10 AM Hold Me Jesus Big Daddy Weave Every Time I Breathe (2006) 12:03:59 AM Do Something Matthew West Into The Light 12:07:59 AM Wonderful Merciful Savior Selah Press On (2001) 12:12:20 AM Jesus Loves Me Chris Tomlin Love Ran Red (2014) 12:15:45 AM Crown Him With Many Crowns Michael W. Smith/Anointed I'll Lead You Home (1995) 12:21:51 AM Gloria Todd Agnew Need (2009) 12:24:36 AM Glory Phil Wickham The Ascension (2013) 12:27:47 AM Do Everything Steven Curtis Chapman Do Everything (2011) 12:31:29 AM O Love Of God Laura Story God Of Every Story (2013) 12:34:26 AM Hear My Worship Jaime Jamgochian Reason To Live (2006) 12:37:45 AM Broken Together Casting Crowns Thrive (2014) 12:42:04 AM Love Has Come Mark Schultz Come Alive (2009) 12:45:49 AM Reach Beyond Phil Stacey/Chris August Single (2015) 12:51:46 AM He Knows Your Name Denver & the Mile High Orches EP 12:55:16 AM More Than Conquerors Rend Collective The Art Of Celebration (2014) Praise & Worship from Moody Radio 04/28/15 Tuesday 1 A (CT) Air Time (CT) Title Artist Album 1:00:08 AM You Are My All In All Nichole Nordeman WOW Worship: Yellow (2003) 1:03:59 AM How Can It Be Lauren Daigle How Can It Be (2014) 1:08:12 AM Truth Calvin Nowell Start Somewhere 1:11:57 AM The One Aaron Shust Morning Rises (2013) 1:15:52 AM Great Is Thy Faithfulness Avalon Faith: A Hymns Collection (2006) 1:21:50 AM Beyond Me Toby Mac TBA (2015) 1:25:02 AM Jesus, You Are Beautiful Cece Winans Throne Room 1:29:53 AM No Turning Back Brandon Heath TBA (2015) 1:32:59 AM My God Point of Grace Steady On 1:37:28 AM Let Them See You JJ Weeks Band All Over The World (2009) 1:40:46 AM Yours Steven Curtis Chapman This Moment 1:45:28 AM Burn Bright Natalie Grant Hurricane (2013) 1:51:42 AM Indescribable Chris Tomlin Arriving (2004) 1:55:27 AM Made New Lincoln Brewster Oxygen (2014) Praise & Worship from Moody Radio 04/28/15 Tuesday 2 A (CT) Air Time (CT) Title Artist Album 2:00:09 AM Beautiful MercyMe The Generous Mr. -

Purity for Life Handout for Parents

Purity for Life Handout for Parents Milestone 4: Purity for Life Welcome to Purity for Life. The goal of this seminar is to take a holistic approach to purity in all of life according to Scripture and to prepare families to celebrate the Milestone: Purity for Life together. God has said a great deal concerning purity in the life of every believer. As adolescence flows into everyday life, the issue of purity will be one that can literally alter life’s course for teenagers. A commitment to physical purity is only part of the story. Without addressing the underlying issues, committing to sexual abstinence will be hollow and often broken. God created the human heart, soul, mind and strength to work cohesively to bring Him glory by following His path for life. Purity for Life is guiding your kids along the path that God has laid for them. “I appeal to you therefore, brothers, by the mercies of God, to present your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and acceptable to God, which is your spiritual worship. Do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewal of our mind, that by testing you may discern what is the will of God, what is good and acceptable and perfect.” Romans 12:1-2 The Adolescent Pressures of Life During Milestone 3, the pressures of life on adolescents are discussed in detail. These pressures highly impact this roller coaster ride of emotions, hormones and physical development. Influence from every aspect of life is attempting to define your child’s worth and purpose. -

Congratulations, George. No Wonder They Call You "King"

A D V E R T I S E M E N T r EXPERIENCE THE BUZZ MA" 3 2003 56 NUMBER ONE SINGLES 32 PLATINUM ALBUMS COUNTRY MUSIC HALL OF FAME MEMBER COUNTRY ALBUM OF THE YEAR Congratulations, George. No wonder they call you "King" www.billboand.com www.billboerd.biz US $6.99 CAN $8 99 UK £5.50 99uS Y8.:9CtiN 18> MCA NASHVILLE #13INCT - SCII 3 -DIGIT 907 413124083434 MARI0 REG A04 000!004 s, 200: MCA Nashville 'lllllllliLlllllllulii llll IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIfII I MONTY G2EENIY 0027 l 3740 ELA AVE 4 P o 1 96 L7-Z0`_ 9 www.GeorgeStrait.co LONG BE.1CB CA 90807 -3 IC? "001160 www.americanradiohistory.com ATTENTION INDIE MUSICIANS! THE IMWS IS NOW ACCEPTING ENTRIES. DISC MAKERS" Independent Music World Series In 2008, the IMWS will award over $250,000 in cash GOSPEL, METAL, and prizes to independent musicians. No matter HIP HOP, PUNK, where you live, you are eligible to enter now! JAZZ, COUNTRY, EMO, ROCK, RAP, Whatever your act is... REGGAETON, we've showcased your style of music. AND MANY MORE! Deadline for entries is May 14, 2008 2008 Showcases in LOS ANGELES, ATLANTA, CHICAGO, and NEW YORK CITY. VISIT WWW.DISCMAKERS.COM /08BILLBOARD TO ENTER, READ THE RULES AND REGULATIONS, FIND OUT ABOUT PAST SHOWCASES, SEE PHOTOS,AND LEARN ALL ABOUT THE GREAT IMWS PRIZE PACKAGE. CAN'T GET ONLINE? CALL 1 -888- 800-5796 FOR MORE INFO. i/, Billboard sonicbíds,- REMO `t¡' 0 SAMSON' cakewalk DRUM! Dc.!1/Watk4 Remy sHvRE SLIM z=rn EleCtronic Musicioo www.americanradiohistory.com THEATER TWEETERS CONCERTS CASH IN AT THE MOVIES >P.27 DEF JAMMED LIFE AFTER JAY-Z FOR THE ROOTS -

Pg0140 Layout 1

New Releases HILLSONG UNITED: LIVE IN MIAMI Table of Contents Giving voice to a generation pas- Accompaniment Tracks . .14, 15 sionate about God, the modern Bargains . .20, 21, 38 rock praise & worship band shares 22 tracks recorded live on their Collections . .2–4, 18, 19, 22–27, sold-out Aftermath Tour. Includes 31–33, 35, 36, 38, 39 the radio single “Search My Heart,” “Break Free,” “Mighty to Save,” Contemporary & Pop . .6–9, back cover “Rhythms of Grace,” “From the Folios & Songbooks . .16, 17 Inside Out,” “Your Name High,” “Take It All,” “With Everything,” and the Gifts . .back cover tour theme song. Two CDs. Hymns . .26, 27 $ 99 KTCD23395 Retail $14.99 . .CBD Price12 Inspirational . .22, 23 Also available: Instrumental . .24, 25 KTCD28897 Deluxe CD . 19.99 15.99 KT623598 DVD . 14.99 12.99 Kids’ Music . .18, 19 Movie DVDs . .A1–A36 he spring and summer months are often New Releases . .2–5 Tpacked with holidays, graduations, celebra- Praise & Worship . .32–37 tions—you name it! So we had you and all your upcoming gift-giving needs in mind when we Rock & Alternative . .10–13 picked the products to feature on these pages. Southern Gospel, Country & Bluegrass . .28–31 You’ll find $5 bargains on many of our best-sell- WOW . .39 ing albums (pages 20 & 21) and 2-CD sets (page Search our entire music and film inventory 38). Give the special grad in yourConGRADulations! life something unique and enjoyable with the by artist, title, or topic at Christianbook.com! Class of 2012 gift set on the back cover. -

AUDIO + VIDEO 9/14/10 Audio & Video Releases *Click on the Artist Names to Be Taken Directly to the Sell Sheet

NEW RELEASES WEA.COM ISSUE 18 SEPTEMBER 14 + SEPTEMBER 21, 2010 LABELS / PARTNERS Atlantic Records Asylum Bad Boy Records Bigger Picture Curb Records Elektra Fueled By Ramen Nonesuch Rhino Records Roadrunner Records Time Life Top Sail Warner Bros. Records Warner Music Latina Word AUDIO + VIDEO 9/14/10 Audio & Video Releases *Click on the Artist Names to be taken directly to the Sell Sheet. Click on the Artist Name in the Order Due Date Sell Sheet to be taken back to the Recap Page Street Date DV- En Vivo Desde Morelia 15 LAT 525832 BANDA MACHOS Años (DVD) $12.99 9/14/10 8/18/10 CD- FER 888109 BARLOWGIRL Our Journey…So Far $11.99 9/14/10 8/25/10 CD- NON 524138 CHATHAM, RHYS A Crimson Grail $16.98 9/14/10 8/25/10 CD- ATL 524647 CHROMEO Business Casual $13.99 9/14/10 8/25/10 CD- Business Casual (Deluxe ATL 524649 CHROMEO Edition) $18.98 9/14/10 8/25/10 Business Casual (White ATL A-524647 CHROMEO Colored Vinyl) $18.98 9/14/10 8/25/10 DV- Crossroads Guitar Festival RVW 525705 CLAPTON, ERIC 2004 (Super Jewel)(2DVD) $29.99 9/14/10 8/18/10 DV- Crossroads Guitar Festival RVW 525708 CLAPTON, ERIC 2007 (Super Jewel)(2DVD) $29.99 9/14/10 8/18/10 COLMAN, Shape Of Jazz To Come (180 ACG A-1317 ORNETTE Gram Vinyl) $24.98 9/14/10 8/25/10 REP A-524901 DEFTONES White Pony (2LP) $26.98 9/14/10 8/25/10 CD- RRR 177622 DRAGONFORCE Twilight Dementia (Live) $18.98 9/14/10 8/25/10 DV- LAT 525829 EL TRI Sinfonico (DVD) $12.99 9/14/10 8/18/10 JACKSON, MILT & HAWKINS, ACG A-1316 COLEMAN Bean Bags (180 Gram Vinyl) $24.98 9/14/10 8/25/10 CD- NON 287228 KREMER, GIDON -

How to Order by Phone Call the Hal Leonard E-Z Order Line at 1-800-554-0626, Monday Through Friday Between 8:30 A.M

HOW TO ORDER By Phone Call the Hal Leonard E-Z Order Line at 1-800-554-0626, Monday through Friday between 8:30 a.m. and 9:00 p.m. or Saturday and Sunday 9:00 a.m. - 5:00 C.S.T. Please have ready the following information: • Your customer account number • Your purchase order number • Special shipping instructions (if any) • Quantity of each item • Hal Leonard inventory number of each item (the 8-digit number listed with all products) By Fax You may fax your order to 414-774-3259. Be sure to put “Attention: Sales” on your cover page, and include all of the same information listed under the “By Phone” section. By E-Mail Simply e-mail us at [email protected] with the same information as above. By Mail For stock orders, simply indicate the quantity of each item you wish to order directly in this catalog and mail it back to us. A Hal Leonard sales representative will be happy to provide you with a replacement catalog. On Line Visit Hal Leonard on the internet at http://www.halleonard.com/dealers. Ask your sales rep about our dealer access web features. International Orders For international inquiries, please contact the Hal Leonard International Sales Department at [email protected]. Canadian Dealers, please contact the Sales Representative for Canada at [email protected]. Customer Service Should you have any questions regarding your account (shipping, orders, etc.), please call our Customer Service Department in Winona, Minnesota, toll-free at 1-800-321-3408 Monday through Friday between 8:00 a.m. -

^4Jfong FRIENDS

Ttos BETHEL UNIVERSITY L'. -VJARY ^4jfONG FRIENDS VOLUME 7, NUMBER 1 AUTUMN 2006 SET SAIL WITH US AT HOMECOMING 2006! FRIENDS OF THE By: Verena Larson John has led a rich and inter Of course there will be LIBRARY esting life which you can read refreshments and time to chat We will be Sailing into the HOMECOMING about below. with other Friends. Sea of Knowledge as we highlight OPEN HOUSE the benefits and joys of lifelong We will also hear how learning. other Friends have made life long learning an important SATURDAY Bethel Friend, John Law part of their lives, experienc yer, has donated his Great SEPTEMBER 30 ing everything from scuba Courses series to the library. diving to Elderhostel. 10:00-11:30 This extensive collection of videos and CDs covers a wide We'll invite you to share BETHEL variety of topics in religion, your experiences and questions UNIVERSITY philosophy, history, music, on your voyage of lifelong LIBRARY drama, and more. John will learning. Be thinking about tell us how he discovered what you have learned since See you September 30th! them, how he uses them, and leaving school and what you what he gets out of them. still want to learn. BETHEL FACULTY CORNER By: Nancy Olson versity of Delaware while he land studying the impact of INSIDE THIS ISSUE: was based at Dover Air Force current changes in Europe and Friend of the BUL and Be Base. In 1970, he obtained a Russia on U.S. foreign policy. thel University Professor, John Master of Public Administra BETHEL FACULTY 2 E. -

Visual Representations of Christianity in Christian Music Videos

Visual Representations of Christianity in Christian Music Videos ANDREAS HÄGER Åbo Akademi University Abstract This article discusses Christian rock videos. Videos from a collection entitled Wow Hits 2002: the year’s top Christian music videos are used as examples. The title of the collection declares that the videos are “Christian”, and the question asked in the article is how this quality may be seen in the videos. How may the videos be seen as visual representations of Christianity? Using a semiotic framework, two possible types of such representations of Christianity in the videos are discussed. These are references to traditional Christian imagery; and the style and appearance of the artists. This article discusses Christian rock videos as an example of the interaction between religion and popular culture. The genre of “contemporary Christian music”, or Christian rock, by being rock music as well as an expression of Christianity, stands with one foot in institutional (often evangelical) Chris tianity and the other in the secular commercial music industry. This article studies how this ambiguous position is manifested in Christian rock videos. Examples will be taken from the Christian hit video collection Wow hits 2002: the year’s top Christian music videos. © The Finnish Society for the Study of Religion Temenos Vol. 41 No. 2 (2005), 251–274 252 ANDREAS HÄGER The research context for the article is constituted by two overlapping fields of research: sociology of religion and the study of religion and popu lar culture. The view here is that these fields are connected, as the relation between religion and popular culture is understood as an example of the overarching topic of the sociology of religion: the role of religion in con temporary society. -

Music and Shopping Suggestions

Looking for Something Similar to Disney Channel Artists? BarlowGirl Point of Grace ZoeGirl Francesca Battistelli Superchick Jamie Grace Fireflight Mandisa Britt Nicole Looking for Christian Rappers? Lecrae Tedashii Tobymac Looking for Something Similar to Popular Rock and Pop Bands? Switchfoot Newsboys Skillet Thousand Foot Krutch Building 429 RED Kutless Relient K Tenth Avenue North Hawk Nelson Group I Crew Jars of Clay Hollyn Everyday Sunday David Crowder Band Third Day Looking for Great Christian Artists? Danielle Rose Hillsong Young & Free Laura Story Audrey Assad Amy Grant Sarah Kroger Natalie Grant Marie Miller Rich Mullins L’Angelus Brother Isaiah Emily Wilson Avalon Elevation Worship Phil Joel Plumb Casting Crowns Matt Maher Luke Sephar All Sons & Daughters Mindy Smith Bethel Music NeedToBreath Fernando Ortega Mercy Me Katie Rose Hillsong United Aly Aleigha Andrew Peterson Land’s End (Check out their overstock section on the website or their seasonal clearance in the back of the store). Modcloth and Unique Vintage for modest swimsuits. L.L.Bean, Down East Basics, Mikarose Clothing, Lime Ricki koshercasual.com ("What I like about this particular site is the layering pieces. As There are half tees that are high-necked, yet don't bulk up an otherwise pretty dress or top. Also, the skirts are nicely cut and knee length”) eshakti.com (My pre-teen and teen daughters and I have all purchased from eShakti. Not all dresses are modestly cut, but for an additional $9.95 you have the option to customize your dress length, neck style, and sleeve length as well as have it made to fit your measurements.) Thrift Stores & Garage Sales Marshall’s, T.J. -

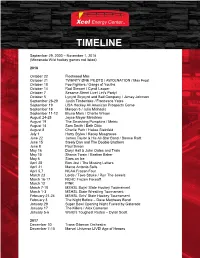

Xcel Energy Center Timeline

TIMELINE September 29, 2000 – November 1, 2018 (Minnesota Wild hockey games not listed) 2018 October 22 Fleetwood Mac October 21 TWENTY ØNE PILØTS / AWOLNATION / Max Frost October 18 Foo Fighters / Gangs of Youths October 14 Rod Stewart / Cyndi Lauper October 7 Sesame Street Live! Let’s Party! October 5 Lynyrd Skynyrd and Bad Company / Jamey Johnson September 28-29 Justin Timberlake / Francesco Yates September 19 USA Hockey All American Prospects Game September 18 Maroon 5 / Julia Michaels September 11-12 Bruno Mars / Charlie Wilson August 24-25 Joyce Meyer Ministries August 19 The Smashing Pumpkins / Metric August 14 Sam Smith / Beth Ditto August 8 Charlie Puth / Hailee Steinfeld July 1 Harry Styles / Kacey Musgraves June 22 James Taylor & His All-Star Band / Bonnie Raitt June 15 Steely Dan and The Doobie Brothers June 8 Paul Simon May 16 Daryl Hall & John Oates and Train May 15 Shania Twain / Bastian Baker May 6 Stars on Ice April 28 Bon Jovi / The Missing Letters April 21 Marco Antonio Solis April 5,7 NCAA Frozen Four March 23 Lorde / Tove Stryke / Run The Jewels March 16-17 NCHC Frozen Faceoff March 12 P!NK March 7-10 MSHSL Boys’ State Hockey Tournament March 1-3 MSHSL State Wrestling Tournament February 21-24 MSHSL Girls’ State Hockey Tournament February 3 The Night Before – Dave Matthews Band January 29 Super Bowl Opening Night Fueled by Gatorade January 17 The Killers / Alex Cameron January 5-6 World’s Toughest Rodeo – Dylan Scott 2017 December 30 Trans-Siberian Orchestra December 7-10 Marvel Universe LIVE! Age of Heroes 1 December 4 101.3 KDWB Jingle Ball - Fall Out Boy / Kesha / Charlie Puth / Halsey / Niall Horan / Camila Cabello / Liam Payne / Julia Michaels / Why Don't We December 3 U.S. -

A Semiological Analysis of Contemporary Christian Music (Ccm) As Heard on 95.5 Wfhm-Fm Cleveland, Ohio "The Fish" Radio Station (July 2001 to July 2006)

A SEMIOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF CONTEMPORARY CHRISTIAN MUSIC (CCM) AS HEARD ON 95.5 WFHM-FM CLEVELAND, OHIO "THE FISH" RADIO STATION (JULY 2001 TO JULY 2006) A dissertation submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Alexandra A. Vago May 2011 Dissertation written by Alexandra A. Vago B.S., Temple University, 1994 M.M., Kent State University, 1998 M.A., Kent State University, 2001 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2011 Approved by ___________________________, Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Denise Seachrist ___________________________, Co-Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Ralph Lorenz ___________________________, Members, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Thomas Janson ___________________________, David Odell-Scott Accepted by ___________________________, Director, School of Music Denise Seachrist ___________________________, Dean, College of the Arts John R. Crawford ii TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS...................................................................................................iii! LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................................................... iv! ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................. v! CHAPTER ! I. 95.5 FM: FROM WCLV TO WFHM "THE FISH"! A Brief History ............................................................................................ 6! Why Radio?..............................................................................................