Visual Representations of Christianity in Christian Music Videos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Losing My Voice 1P.Indd 3 6/14/19 12:50 PM Losing My Voice 1P.Indd 4 6/14/19 12:50 PM Losing My Voice to Find It MARK STUART STORY

losing my voice to find it Losing My Voice_1P.indd 3 6/14/19 12:50 PM Losing My Voice_1P.indd 4 6/14/19 12:50 PM losing my voice to find it MARK STUART STORY MARK STUART Losing My Voice_1P.indd 5 6/14/19 12:50 PM © 2019 Mark Stuart All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means— electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, scanning, or other— except for brief quotations in critical reviews or articles, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Published in Nashville, Tennessee, by Nelson Books, an imprint of Thomas Nelson. Nelson Books and Thomas Nelson are registered trademarks of HarperCollins Christian Publishing, Inc. Thomas Nelson titles may be purchased in bulk for educational, business, fund- raising, or sales promotional use. For information, please e- mail [email protected]. Scripture quotations are taken from the Holy Bible, New International Version®, NIV®. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.® Used by permission of Zondervan. All rights reserved worldwide. www.Zondervan.com. The “NIV” and “New International Version” are trademarks registered in the United States Patent and Trademark Office by Biblica, Inc.® Any Internet addresses, phone numbers, or company or product information printed in this book are offered as a resource and are not intended in any way to be or to imply an endorsement by Thomas Nelson, nor does Thomas Nelson vouch for the existence, content, or services of these sites, phone numbers, companies, or products beyond the life of this book. -

Directory of Contemporary Worship Musicians

1 Directory of Contemporary Worship Musicians Copyright 2011 by David W. Cloud This edition February 4, 2012 ISBN 978-1-58318-131-7 This book is published for free distribution in eBook format. It is available in PDF, MOBI (for Kindle, etc.), and ePUB formats from the Way of Life web site. See the Free Book tab. Published by Way of Life Literature PO Box 610368, Port Huron, MI 48061 866-295-4143 (toll free) - [email protected] www.wayoflife.org Canada: Bethel Baptist Church 4212 Campbell St. N., London Ont. N6P 1A6 519-652-2619 (voice) - 519-652-0056 (fax) [email protected] Printed in Canada by Bethel Baptist Print Ministry 2 Table of Contents Powerful Publications for These Times ......................6 About Way of Life’s eBooks ....................................13 Introduction............................................................... 15 7eventh Time Down ...........................................18 Abandon .............................................................20 Assad, Audrey.................................................... 23 Baloche, Paul...................................................... 24 Beatles and CCM............................................... 26 Brown, Brenton ..................................................34 Caedmon’s Call ..................................................35 Calvary Chapel and Maranatha Music ...............40 Card, Michael .....................................................55 Carman ...............................................................60 Carouthers, Mark ...............................................66 -

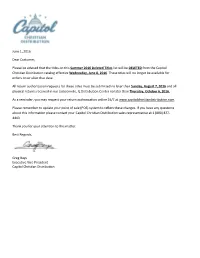

June 1, 2016 Dear Customer, Please Be Advised That the Titles On

June 1, 2016 Dear Customer, Please be advised that the titles on this Summer 2016 Deleted Titles list will be DELETED from the Capitol Christian Distribution catalog effective Wednesday, June 8, 2016. These titles will no longer be available for orders on or after that date. All return authorization requests for these titles must be submitted no later than Sunday, August 7, 2016 and all physical returns received in our Jacksonville, IL Distribution Center no later than Thursday, October 6, 2016. As a reminder, you may request your return authorization online 24/7 at www.capitolchristiandistribution.com. Please remember to update your point of sale (POS) system to reflect these changes. If you have any questions about this information please contact your Capitol Christian Distribution sales representative at 1 (800) 877- 4443. Thank you for your attention to this matter. Best Regards, Greg Bays Executive Vice President Capitol Christian Distribution CAPITOL CHRISTIAN DISTRIBUTION SUMMER 2016 DELETED TITLES LIST Return Authorization Due Date August 7, 2016 • Physical Returns Due Date October 6, 2016 RECORDED MUSIC ARTIST TITLE UPC LABEL CONFIG Amy Grant Amy Grant 094639678525 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant My Father's Eyes 094639678624 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant Never Alone 094639678723 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant Straight Ahead 094639679225 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant Unguarded 094639679324 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant House Of Love 094639679829 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant Behind The Eyes 094639680023 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant A Christmas To Remember 094639680122 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant Simple Things 094639735723 Amy Grant Productions CD Amy Grant Icon 5099973589624 Amy Grant Productions CD Seventh Day Slumber Finally Awake 094635270525 BEC Recordings CD Manafest Glory 094637094129 BEC Recordings CD KJ-52 The Yearbook 094637829523 BEC Recordings CD Hawk Nelson Hawk Nelson Is My Friend 094639418527 BEC Recordings CD The O.C. -

The Slow Integration of Instruments Into Christian Worship

Musical Offerings Volume 8 Number 1 Spring 2017 Article 2 3-28-2017 From Silence to Golden: The Slow Integration of Instruments into Christian Worship Jonathan M. Lyons Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/musicalofferings Part of the Christianity Commons, Fine Arts Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Musicology Commons, and the Music Performance Commons DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Recommended Citation Lyons, Jonathan M. (2017) "From Silence to Golden: The Slow Integration of Instruments into Christian Worship," Musical Offerings: Vol. 8 : No. 1 , Article 2. DOI: 10.15385/jmo.2017.8.1.2 Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/musicalofferings/vol8/iss1/2 From Silence to Golden: The Slow Integration of Instruments into Christian Worship Document Type Article Abstract The Christian church’s stance on the use of instruments in sacred music shifted through influences of church leaders, composers, and secular culture. Synthesizing the writings of early church leaders and church historians reveals a clear progression. The early musical practices of the church were connected to the Jewish synagogues. As recorded in the Old Testament, Jewish worship included instruments as assigned by one’s priestly tribe. -

Music for Contemporary Christians: What, Where, and When?

Journal of the Adventist Theological Society, 13/1 (Spring 2002): 184Ð209. Article copyright © 2002 by Ed Christian. Music for Contemporary Christians: What, Where, and When? Ed Christian Kutztown University of Pennsylvania What music is appropriate for Christians? What music is appropriate in worship? Is there a difference between music appropriate in church and music appropriate in a youth rally or concert? Is there a difference between lyrics ap- propriate for congregational singing and lyrics appropriate for a person to sing or listen to in private? Are some types of music inherently inappropriate for evangelism?1 These are important questions. Congregations have fought over them and even split over them.2 The answers given have often alienated young people from the church and even driven them to reject God. Some answers have rejuve- nated congregations; others have robbed congregations of vitality and shackled the work of the Holy Spirit. In some churches the great old hymns havenÕt been heard in years. Other churches came late to the Òpraise musicÓ wars, and music is still a controversial topic. Here, where praise music is found in the church service, it is probably accompanied by a single guitar or piano and sung without a trace of the enthusi- asm, joy, emotion, and repetition one hears when it is used in charismatic churches. Many churches prefer to use no praise choruses during the church service, some use nothing but praise choruses, and perhaps the majority use a mixture. What I call (with a grin) Òrock ÔnÕ roll church,Ó where such instruments 1 Those who have recently read my article ÒThe Christian & Rock Music: A Review-Essay,Ó may turn at once to the section headed ÒThe Scriptural Basis.Ó Those who havenÕt read it should read on. -

The Liberty Champion, Volume 11, Issue 23)

Scholars Crossing 1993 -- 1994 Liberty University School Newspaper 4-26-1994 04-26-94 (The Liberty Champion, Volume 11, Issue 23) Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/paper_93_94 Recommended Citation "04-26-94 (The Liberty Champion, Volume 11, Issue 23)" (1994). 1993 -- 1994. 24. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/paper_93_94/24 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Liberty University School Newspaper at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in 1993 -- 1994 by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ^^"" _J J B Nonprofit org. ' ' U.S. Postage liversity, Lynchburg, Va. Tuesday. April 26,19926,19944 , Vol. 11, No. 23 LJS . va INSIDE: SGA to sponsor IN THE NEWS: Student senate will be ratifying the new Student Government Association constitution, on Thurs 'Spring Fling' party day, April 28. Page 2. By IVETTE HASSAN nal exams." Party include: airball for 18 Champion Reporter He also added that "we want people, bouncy boxing, gyro, CAMPUS C ALENDAR! Students encouraged to to leave the students in a good horizontal bungee run, dunking Liberty University's Student m help clean up the Liberty University campus. SG A will offer note at the end of the year." booth (with administrators, fac Life office will hold its second special prizes to students who participate. Page 2. "(The Block Party) is a time ulty and staff), two portable bas- "Block Party" on Saturday, May at the beginning and at the end ketball hoops and several 7, in the DeMoss parking lot, of the year where students can pingpong tables. -

Cedars, November 15, 1996 Cedarville College

Masthead Logo Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Cedars 11-15-1996 Cedars, November 15, 1996 Cedarville College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/cedars Part of the Journalism Studies Commons, and the Organizational Communication Commons DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a platform for archiving the scholarly, creative, and historical record of Cedarville University. The views, opinions, and sentiments expressed in the articles published in the university’s student newspaper, Cedars (formerly Whispering Cedars), do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The uthora s of, and those interviewed for, the articles in this paper are solely responsible for the content of those articles. Please address questions to [email protected]. Recommended Citation Cedarville College, "Cedars, November 15, 1996" (1996). Cedars. 686. https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/cedars/686 This Issue is brought to you for free and open access by Footer Logo DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cedars by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. How Much Do You Owe? Students At Olympics. • •••••••• PAGE 4 Grandparent's Day.... Mister Smith Goes Student Profile........... to Cedorville Business Etiquette. • •••••••• PAGE 6 Do You Know If You're A Senior? News shorts. • •••••••• PAGE 9 CEDARVILLE COLLEGE STUDENT PUBLICATION Basketball teams rise to opening night against W ilberforce Mark Mien Lady Jacket bench proved to be the Staff Writer difference. All 14 members of the So long fall, hello winter. Yep, it squad played, and 12 of them scor is that time of the year again. -

Sparrow Records Discography

Sparrow Discography by Mike Callahan, David Edwards & Patrice Eyries © 2018 by Mike Callahan Sparrow Records Discography Sparrow is a Contemporary Christian label founded in 1976 by Billy Ray Hearn. Hearn was the A&R Director for Word Records’ Myrrh label, founded a few years earlier also as a Contemporary Christian label. Sparrow also released records under their Birdwing subsidiary. Hearn’s Sparrow label was in competition with Hearn’s old boss, Word Records, and was quite successful. Even today, Sparrow is among the top Christian labels. Hearn sold the label to EMI in 1992, and it was placed under the Capitol Christian Music Group. Sparrow signed a distribution agreement with MCA in April, 1981 to release their product in the secular market while the regular Sparrow issues were distributed to Christian stores and Christian radio stations. The arrangement with MCA lasted until October, 1986, when Sparrow switched distribution to Capitol. Sparrow SPR-1001 Main Series: SPR-1001 - Through a Child’s Eyes - Annie Herring [1976] Learn A Curtsey/Where Is The Time/Wild Child/Death After Life/Grinding Stone/Hand On Me//Dance With You/Love Drops/Days Like These/First Love/Some Days/Liberty Bird/Fly Away Burden SPR-1002 - SPR-1003 - John Michael Talbot - John Michael Talbot [1976] He Is Risen/Jerusalem/How Long/Would You Crucify Him//Woman/Greewood Suite/Hallelu SPR-1004 - Firewind - Various Artists [1976] Artists include Anne Herring, Barry McGuire, John Talbot, Keith Green, Matthew Ward, Nelly Ward, and Terry Talbot (In other words, Barry McGuire, The Talbot Brothers, Keith Green, and The 2nd Chapter of Acts). -

Contemporary Christian Music & The

PLAYING THE MARKET: CONTEMPORARY CHRISTIAN MUSIC & THE THEORY OF RELIGIOUS ECONOMY by Jamie Carrick B.A., The University of Calgary, 2007 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Religious Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) October 2012 © Jamie Carrick, 2012 Abstract Contemporary Christian music (CCM) is a fascinating and understudied part of the religious vitality of modern American religion. In this dissertation the theory of religious economy is proposed as a valuable and highly serviceable methodological approach for the scholarly study of CCM. The theory of religious economy, or the marketplace approach, incorporates economic concepts and terminology in order to better explain American religion in its distinctly American context. In this study, I propose three ways in which this method can be applied. Firstly, I propose that CCM artists can be identified as religious firms operating on the “supply-side” of the religio-economic dynamic; it is their music, specifically the diverse brands of Christianity espoused there within, that can allow CCM artists to be interpreted in such a way. Secondly, the diversity within the public religious expressions of CCM artists can be recognized as being comparable to religious pluralism in a free marketplace of religion. Finally, it is suggested that the relationship between supply-side firms is determined, primarily, by the competitive reality of a free market religious economy. ii Table of Contents Abstract . ii Table of Contents . iii List of Figures . iv Acknowledgements . v 1 Introduction . 1 1.1 Introduction . 1 1.2 Religion & Popular Culture . -

Praise & Worship from Moody Radio

Praise & Worship from Moody Radio 04/28/15 Tuesday 12 A (CT) Air Time (CT) Title Artist Album 12:00:10 AM Hold Me Jesus Big Daddy Weave Every Time I Breathe (2006) 12:03:59 AM Do Something Matthew West Into The Light 12:07:59 AM Wonderful Merciful Savior Selah Press On (2001) 12:12:20 AM Jesus Loves Me Chris Tomlin Love Ran Red (2014) 12:15:45 AM Crown Him With Many Crowns Michael W. Smith/Anointed I'll Lead You Home (1995) 12:21:51 AM Gloria Todd Agnew Need (2009) 12:24:36 AM Glory Phil Wickham The Ascension (2013) 12:27:47 AM Do Everything Steven Curtis Chapman Do Everything (2011) 12:31:29 AM O Love Of God Laura Story God Of Every Story (2013) 12:34:26 AM Hear My Worship Jaime Jamgochian Reason To Live (2006) 12:37:45 AM Broken Together Casting Crowns Thrive (2014) 12:42:04 AM Love Has Come Mark Schultz Come Alive (2009) 12:45:49 AM Reach Beyond Phil Stacey/Chris August Single (2015) 12:51:46 AM He Knows Your Name Denver & the Mile High Orches EP 12:55:16 AM More Than Conquerors Rend Collective The Art Of Celebration (2014) Praise & Worship from Moody Radio 04/28/15 Tuesday 1 A (CT) Air Time (CT) Title Artist Album 1:00:08 AM You Are My All In All Nichole Nordeman WOW Worship: Yellow (2003) 1:03:59 AM How Can It Be Lauren Daigle How Can It Be (2014) 1:08:12 AM Truth Calvin Nowell Start Somewhere 1:11:57 AM The One Aaron Shust Morning Rises (2013) 1:15:52 AM Great Is Thy Faithfulness Avalon Faith: A Hymns Collection (2006) 1:21:50 AM Beyond Me Toby Mac TBA (2015) 1:25:02 AM Jesus, You Are Beautiful Cece Winans Throne Room 1:29:53 AM No Turning Back Brandon Heath TBA (2015) 1:32:59 AM My God Point of Grace Steady On 1:37:28 AM Let Them See You JJ Weeks Band All Over The World (2009) 1:40:46 AM Yours Steven Curtis Chapman This Moment 1:45:28 AM Burn Bright Natalie Grant Hurricane (2013) 1:51:42 AM Indescribable Chris Tomlin Arriving (2004) 1:55:27 AM Made New Lincoln Brewster Oxygen (2014) Praise & Worship from Moody Radio 04/28/15 Tuesday 2 A (CT) Air Time (CT) Title Artist Album 2:00:09 AM Beautiful MercyMe The Generous Mr. -

4X GRAMMY® AWARD WINNING DUO for KING & COUNTRY TO

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE July 6th, 2021 4x GRAMMY® AWARD WINNING DUO for KING & COUNTRY TO EMBARK ON FIRST ARENA TOUR IN TWO YEARS WITH RELATE | THE 2021 FALL TOUR Click Here to Download Admat Nashville, TENN. – After setting an industry record with six consecutive No. 1 hits, 4x GRAMMY Award winning, platinum-selling duo and Curb | Word Entertainment recording artist for KING & COUNTRY are announcing RELATE | The 2021 Fall Tour. After wowing crowds in 2020 with their Pollstar recognized drive-in theater performances, this 24-date trek will see Joel and Luke Smallbone return to the road in compelling fashion, arranging their electrifying live spectacle for arenas and amphitheaters. BRAND NEW, never performed songs from an upcoming studio project will be featured on the tour’s setlist, along with selections from the duo’s nine No. 1 hits – including “joy.,” “Fix My Eyes,” and the cross-genre multi-week smash “God Only Knows.” This will be fans’ first chance to hear new music straight from the source. for KING & COUNTRY kick things off in Toledo, Ohio on October 7th before wrapping up in Rochester, Minnesota on November 14th. Ticket pre-sale for RELATE | The 2021 Fall Tour starts tomorrow at 10am local time, to access the pre-sale enter the code “RELATE” at the link HERE. Tickets will go on sale to the public July 9th at 10am local time, click HERE for more information. “The thought of hitting the road and seeing you again is a thrilling one,” Joel and Luke Smallbone share in a statement. “Since we were last together, we’ve been hard at work writing and recording new music, which is going to make ‘RELATE | The 2021 Fall Tour’ a particularly special one. -

Music Industry Report 2020 Includes the Work of Talented Student Interns Who Went Through a Competitive Selection Process to Become a Part of the Research Team

2O2O THE RESEARCH TEAM This study is a product of the collaboration and vision of multiple people. Led by researchers from the Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce and Exploration Group: Joanna McCall Coordinator of Applied Research, Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce Barrett Smith Coordinator of Applied Research, Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce Jacob Wunderlich Director, Business Development and Applied Research, Exploration Group The Music Industry Report 2020 includes the work of talented student interns who went through a competitive selection process to become a part of the research team: Alexander Baynum Shruthi Kumar Belmont University DePaul University Kate Cosentino Isabel Smith Belmont University Elon University Patrick Croke University of Virginia In addition, Aaron Davis of Exploration Group and Rupa DeLoach of the Nashville Area Chamber of Commerce contributed invaluable input and analysis. Cluster Analysis and Economic Impact Analysis were conducted by Alexander Baynum and Rupa DeLoach. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 5 - 6 Letter of Intent Aaron Davis, Exploration Group and Rupa DeLoach, The Research Center 7 - 23 Executive Summary 25 - 27 Introduction 29 - 34 How the Music Industry Works Creator’s Side Listener’s Side 36 - 78 Facets of the Music Industry Today Traditional Small Business Models, Startups, Venture Capitalism Software, Technology and New Media Collective Management Organizations Songwriters, Recording Artists, Music Publishers and Record Labels Brick and Mortar Retail Storefronts Digital Streaming Platforms Non-interactive