Women, Theory and Horror Film

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Finn Ballard: No Trespassing: the Post-Millennial

Page 15 No Trespassing: The postmillennial roadhorror movie Finn Ballard Since the turn of the century, there has been released throughout America and Europe a spate of films unified by the same basic plotline: a group of teenagers go roadtripping into the wilderness, and are summarily slaughtered by locals. These films may collectively be termed ‘roadhorror’, due to their blurring of the aesthetic of the road movie with the tension and gore of horror cinema. The thematic of this subgenre has long been established in fiction; from the earliest oral lore, there has been evident a preoccupation with the potential terror of inadvertently trespassing into a hostile environment. This was a particular concern of the folkloric Warnmärchen or ‘warning tale’ of medieval Europe, which educated both children and adults of the dangers of straying into the wilderness. Pioneers carried such tales to the fledging United States, but in a nation conceptualised by progress, by the shining of light upon darkness and the pushing back of frontiers, the fear of the wilderness was diminished in impact. In more recent history, the development of the automobile consolidated the joint American traditions of mobility and discovery, as the leisure activity of the road trip became popular. The wilderness therefore became a source of fascination rather than fear, and the road trip became a transcendental voyage of discovery and of escape from the urban, made fashionable by writers such as Jack Kerouac and by those filmmakers such as Dennis Hopper ( Easy Rider, 1969) who influenced the evolution of the American road movie. -

Locations of Motherhood in Shakespeare on Film

Volume 2 (2), 2009 ISSN 1756-8226 Locations of Motherhood in Shakespeare on Film LAURA GALLAGHER Queens University Belfast Adelman’s Suffocating Mothers (1992) appropriates feminist psychoanalysis to illustrate how the suppression of the female is represented in selected Shakespearean play-texts (chronologically from Hamlet to The Tempest ) in the attempted expulsion of the mother in order to recover the masculine sense of identity. She argues that Hamlet operates as a watershed in Shakespeare’s canon, marking the prominent return of the problematic maternal presence: “selfhood grounded in paternal absence and in the fantasy of overwhelming contamination at the site of origin – becomes the tragic burden of Hamlet and the men who come after him” (1992, p.10). The maternal body is thus constructed as the site of contamination, of simultaneous attraction and disgust, of fantasies that she cannot hold: she is the slippage between boundaries – the abject. Julia Kristeva’s theory of the abject (1982) ostensibly provides a hypothesis for analysis of women in the horror film, yet the theory also provides a critical means of situating the maternal figure, the “monstrous- feminine” in film versions of Shakespeare (Creed, 1993, 1996). Therefore the choice to focus on the selected Hamlet , Macbeth , Titus Andronicus and Richard III film versions reflects the centrality of the mother figure in these play-texts, and the chosen adaptations most powerfully illuminate this article’s thesis. Crucially, in contrast to Adelman’s identification of the attempted suppression of the “suffocating mother” figures 1, in adapting the text to film the absent maternal figure is forced into (an extended) presence on screen. -

Mother Trouble: the Maternal-Feminine in Phallic and Feminist Theory in Relation to Bratta Ettinger's Elaboration of Matrixial Ethics

This is a repository copy of Mother trouble: the maternal-feminine in phallic and feminist theory in relation to Bratta Ettinger's Elaboration of Matrixial Ethics. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/81179/ Article: Pollock, GFS (2009) Mother trouble: the maternal-feminine in phallic and feminist theory in relation to Bratta Ettinger's Elaboration of Matrixial Ethics. Studies in the Maternal, 1 (1). 1 - 31. ISSN 1759-0434 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Mother Trouble: The Maternal-Feminine in Phallic and Feminist Theory in Relation to Bracha Ettinger’s Elaboration of Matrixial Ethics/Aesthetics Griselda Pollock Preface Most of us are familiar with Sigmund Freud’s infamous signing off, in 1932, after a lifetime of intense intellectual and analytical creativity, on the question of psychoanalytical research into femininity. -

The Retriever, Issue 1, Volume 39

18 Features August 31, 2004 THE RETRIEVER Alien vs. Predator: as usual, humans screwed it up Courtesy of 20th Century Fox DOUGLAS MILLER After some groundbreaking discoveries on Retriever Weekly Editorial Staff the part of the humans, three Predators show up and it is revealed that the temple functions as prov- Many of the staple genre franchises that chil- ing ground for young Predator warriors. As the dren of the 1980’s grew up with like Nightmare on first alien warriors are born, chaos ensues – with Elm street or Halloween are now over twenty years Weyland’s team stuck right in the middle. Of old and are beginning to loose appeal, both with course, lots of people and monsters die. their original audience and the next generation of Observant fans will notice that Anderson’s filmgoers. One technique Hollywood has been story is very similar his own Resident Evil, but it exploiting recently to breath life into dying fran- works much better here. His premise is actually chises is to combine the keystone character from sort of interesting – especially ideas like Predator one’s with another’s – usually ending up with a involvement in our own development. Anderson “versus” film. Freddy vs. Jason was the first, and tries to allow his story to unfold and build in the now we have Alien vs. Predator, which certainly style of Alien, withholding the monsters almost will not be the last. Already, the studios have toyed altogether until the second half of the film. This around with making Superman vs. Batman, does not exactly work. -

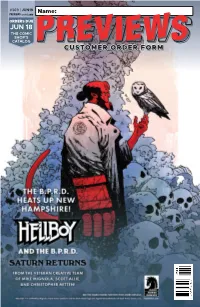

Jun 18 Customer Order Form

#369 | JUN19 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE JUN 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Jun19 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 5/9/2019 3:08:57 PM June19 Humanoids Ad.indd 1 5/9/2019 3:15:02 PM SPAWN #300 MARVEL ACTION: IMAGE COMICS CAPTAIN MARVEL #1 IDW PUBLISHING BATMAN/SUPERMAN #1 DC COMICS COFFIN BOUND #1 GLOW VERSUS IMAGE COMICS THE STAR PRIMAS TP IDW PUBLISHING BATMAN VS. RA’S AL GHUL #1 DC COMICS BERSERKER UNBOUND #1 DARK HORSE COMICS THE DEATH-DEFYING DEVIL #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT MARVEL COMICS #1000 MARVEL COMICS HELLBOY AND THE B.P.R.D.: SATURN RETURNS #1 ONCE & FUTURE #1 DARK HORSE COMICS BOOM! STUDIOS Jun19 Gem Page.indd 1 5/9/2019 3:24:56 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Bad Reception #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS The Flash: Crossover Crisis Book 1: Green Arrow’s Perfect Shot HC l AMULET BOOKS Archie: The Married Life 10 Years Later #1 l ARCHIE COMICS Warrior Nun: Dora #1 l AVATAR PRESS INC Star Wars: Rey and Pals HC l CHRONICLE BOOKS 1 Lady Death Masterpieces: The Art of Lady Death HC l COFFIN COMICS 1 Oswald the Lucky Rabbit: The Search for the Lost Disney Cartoons l DISNEY EDITIONS Moomin: The Lars Jansson Edition Deluxe Slipcase l DRAWN & QUARTERLY The Poe Clan Volume 1 HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Cycle of the Werewolf SC l GALLERY 13 Ranx HC l HEAVY METAL MAGAZINE Superman and Wonder Woman With Collectibles HC l HERO COLLECTOR Omni #1 l HUMANOIDS The Black Mage GN l ONI PRESS The Rot Volume 1 TP l SOURCE POINT PRESS Snowpiercer Hc Vol 04 Extinction l TITAN COMICS Lenore #1 l TITAN COMICS Disney’s The Lion King: The Official Movie Special l TITAN COMICS The Art and Making of The Expance HC l TITAN BOOKS Doctor Mirage #1 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT The Mall #1 l VAULT COMICS MANGA 2 2 World’s End Harem: Fantasia Volume 1 GN l GHOST SHIP My Hero Academia Smash! Volume 1 GN l VIZ MEDIA Kingdom Hearts: Re:Coded SC l YEN ON Overlord a la Carte Volume 1 GN l YEN PRESS Arifureta: Commonplace to the World’s Strongest Zero Vol. -

Re-Reading the Monstrous-Feminine : Art, Film, Feminism and Psychoanalysis Ebook

RE-READING THE MONSTROUS-FEMININE : ART, FILM, FEMINISM AND PSYCHOANALYSIS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Nicholas Chare | 268 pages | 18 Sep 2019 | Taylor & Francis Ltd | 9781138602946 | English | London, United Kingdom Re-reading the Monstrous-Feminine : Art, Film, Feminism and Psychoanalysis PDF Book More Details Creed challenges this view with a feminist psychoanalytic critique, discussing films such as Alien, I Spit on Your Grave and Psycho. Average rating 4. Name required. Proven Seller with Excellent Customer Service. Enlarge cover. This movement first reached success in the Pitcairn Islands, a British Overseas Territory in before reaching the United States in , and the United Kingdom in where women over thirty were only allowed to vote if in possession of property qualifications or were graduates of a university of the United Kingdom. Sign up Log in. In comparison, both films support the ideas of feminism as they depict women as more than the passive or lesser able figures that Freud and Darwin saw them as. EMBED for wordpress. Doctor of Philosophy University of Melbourne. Her argument that man fears woman as castrator, rather than as castrated, questions not only Freudian theories of sexual difference but existing theories of spectatorship and fetishism, providing a provocative re-reading of classical and contemporary film and theoretical texts. Physical description viii, p. The Bible, if read secularly, is our primal source of horror. The initial display of women as villains despite the little screen time will further allow understanding of the genre of monstrous feminine and the roles and depths allowed in it which may or may not have aided the feminist movement. -

Marty Kline Storyboards

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c88k7d82 No online items Marty Kline storyboards Special Collections Margaret Herrick Library© 2014 Marty Kline storyboards 535 1 Descriptive Summary Title: Marty Kline storyboards Date (inclusive): 1989-1993 Collection number: 535 Creator: Kline, Marty Extent: 1.3 linear feet of papers. Repository: Margaret Herrick Library. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Languages: English Access Available by appointment only. Publication rights Property rights to the physical object belong to the Margaret Herrick Library. Researchers are responsible for obtaining all necessary rights, licenses, or permissions from the appropriate companies or individuals before quoting from or publishing materials obtained from the library. Preferred Citation Marty Kline storyboards, Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Biography Martin A. Kline is an American storyboard artist, production and concept illustrator, and visual effects art director active in film since the 1980s. He served as a storyboard artist on several films directed by Robert Zemeckis. Collection Scope and Content Summary The Marty Kline storyboards span the years 1989-1993 and encompass 1.3 linear feet. There are photocopies of storyboards for three films directed by Robert Zemeckis, BACK TO THE FUTURE PART II (1989), DEATH BECOMES HER (1992), and FORREST GUMP (1993); and one directed by Steven Spielberg, JURASSIC PARK (1993). While the drawings are primarily by Kline, some are drawn by other storyboard artists. Arrangement Arranged in the following series: 1. Production files. Indexing Terms Kline, Marty--Archives. storyboard artists Marty Kline storyboards 535 2. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents PART I. Introduction 5 A. Overview 5 B. Historical Background 6 PART II. The Study 16 A. Background 16 B. Independence 18 C. The Scope of the Monitoring 19 D. Methodology 23 1. Rationale and Definitions of Violence 23 2. The Monitoring Process 25 3. The Weekly Meetings 26 4. Criteria 27 E. Operating Premises and Stipulations 32 PART III. Findings in Broadcast Network Television 39 A. Prime Time Series 40 1. Programs with Frequent Issues 41 2. Programs with Occasional Issues 49 3. Interesting Violence Issues in Prime Time Series 54 4. Programs that Deal with Violence Well 58 B. Made for Television Movies and Mini-Series 61 1. Leading Examples of MOWs and Mini-Series that Raised Concerns 62 2. Other Titles Raising Concerns about Violence 67 3. Issues Raised by Made-for-Television Movies and Mini-Series 68 C. Theatrical Motion Pictures on Broadcast Network Television 71 1. Theatrical Films that Raise Concerns 74 2. Additional Theatrical Films that Raise Concerns 80 3. Issues Arising out of Theatrical Films on Television 81 D. On-Air Promotions, Previews, Recaps, Teasers and Advertisements 84 E. Children’s Television on the Broadcast Networks 94 PART IV. Findings in Other Television Media 102 A. Local Independent Television Programming and Syndication 104 B. Public Television 111 C. Cable Television 114 1. Home Box Office (HBO) 116 2. Showtime 119 3. The Disney Channel 123 4. Nickelodeon 124 5. Music Television (MTV) 125 6. TBS (The Atlanta Superstation) 126 7. The USA Network 129 8. Turner Network Television (TNT) 130 D. -

The Invisible Monstrous-Feminine

THE INVISIBLE MONSTROUS-FEMININE: THE BLAIR WITCH AND HER HETEROTOPIC WOODS Nb A thesis submitted to the faculty of 30 San Francisco State University Z0\S In partial fulfillment of F im the requirements for * the Degree Master of Arts In Cinema by Erez Genish San Francisco, California May 2015 Copyright by Erez Genish 2015 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read The Invisible Monstrous-Feminine: The Blair Witch and her Heterotopic Woods by Erez Genish, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree Master of Arts in Cinema at San Francisco State University. THE INVISIBLE MONSTROUS-FEMININE: THE BLAIR WITCH AND HER HETEROTOPIC WOODS Erez Genish San Francisco, California 2015 What is absent in the pseudo found-footage film of Eduardo Sanchez and Daniel Myrick’s The Blair Witch Project (1999), is the visual depiction of the Blair witch. The nontraditional tactic of leaving the witch in the woods without form stands in contrast to other folklore and fairytales that perpetuated the mythic figure of the crone, an old woman whose decaying body represents the blurred line between life and death. The crone- witch corresponds to Barbara Creed’s notion of the monstrous-feminine and her analysis of Julia Kristeva’s abject. As her polluted, filthy old mark her a phobic referent, the crone-witch becomes the non-object that draws the subject to the regenerative womb. However, what draws a parallel in the BWP between the monstrous-feminine crone and abjection is the witch’s invisibility. -

Twilight Saga

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OTHES DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit Tracing Female Subjectivity and Self-affirmation in Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight Saga Verfasserin Astrid Ernst angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, 2011 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 343 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Anglistik und Amerikanistik (Diplom) Betreuerin Ao. Univ.- Prof. Mag. Dr. Eva Müller-Zettelmann 1 Table of Contents 1. Introduction.......................................................................................................3 2. Tracing Bella’s Subjectivity: Ideal Love as the Only Way Out..........................4 3. Edward and Jacob: Magnets with reversed polarities or two poles of Bella’s existence?.......................................................................................................12 4. The Cullen Vampires: the ideal family and its enemies..................................20 4.1. Carlisle Cullen......................................................................................20 4.2. Esme Cullen.........................................................................................23 4.3. Rosalie Cullen......................................................................................25 4.4. Alice Cullen..........................................................................................28 4.5. The Cullens’ Enemies..........................................................................30 5. Quileute Legends: -

Preston, John, & Bishop, Mark

Preston, John, & Bishop, Mark (2002), Views into the Chinese Room: New Essays on Searle and Artificial Intelligence (Oxford: Oxford University Press), xvi + 410 pp., ISBN 0-19-825057-6. Reviewed by: William J. Rapaport Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Department of Philosophy, and Center for Cognitive Science, State University of New York at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY 14260-2000; [email protected], http://www.cse.buffalo.edu/ rapaport ∼ This anthology’s 20 new articles and bibliography attest to continued interest in Searle’s (1980) Chinese Room Argument. Preston’s excellent “Introduction” ties the history and nature of cognitive science, computation, AI, and the CRA to relevant chapters. Searle (“Twenty-One Years in the Chinese Room”) says, “purely . syntactical processes of the implemented computer program could not by themselves . guarantee . semantic content . essential to human cognition” (51). “Semantic content” appears to be mind-external entities “attached” (53) to the program’s symbols. But the program’s implementation must accept these entities as input (suitably transduced), so the program in execution, accepting and processing this input, would provide the required content. The transduced input would then be internal representatives of the external content and would be related to the symbols of the formal, syntactic program in ways that play the same roles as the “attachment” relationships between the external contents and the symbols (Rapaport 2000). The “semantic content” could then just be those mind-internal -

Negotiating the Non-Narrative, Aesthetic and Erotic in New Extreme Gore

NEGOTIATING THE NON-NARRATIVE, AESTHETIC AND EROTIC IN NEW EXTREME GORE. A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Communication, Culture, and Technology By Colva Weissenstein, B.A. Washington, DC April 18, 2011 Copyright 2011 by Colva Weissenstein All Rights Reserved ii NEGOTIATING THE NON-NARRATIVE, AESTHETIC AND EROTIC IN NEW EXTREME GORE. Colva O. Weissenstein, B.A. Thesis Advisor: Garrison LeMasters, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This thesis is about the economic and aesthetic elements of New Extreme Gore films produced in the 2000s. The thesis seeks to evaluate film in terms of its aesthetic project rather than a traditional reading of horror as a cathartic genre. The aesthetic project of these films manifests in terms of an erotic and visually constructed affective experience. It examines the films from a thick descriptive and scene analysis methodology in order to express the aesthetic over narrative elements of the films. The thesis is organized in terms of the economic location of the New Extreme Gore films in terms of the film industry at large. It then negotiates a move to define and analyze the aesthetic and stylistic elements of the images of bodily destruction and gore present in these productions. Finally, to consider the erotic manifestations of New Extreme Gore it explores the relationship between the real and the artificial in horror and hardcore pornography. New Extreme Gore operates in terms of a kind of aesthetic, gore-driven pornography. Further, the films in question are inherently tied to their economic circumstances as a result of the significant visual effects technology and the unstable financial success of hyper- violent films.