Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bioregions of NSW: Cobar Peneplain

105 CHAPTER 9 The Cobar Peneplain Bioregion Cobar Cobar Peneplain 1. Location the Barwon, Macquarie, Yanda, Darling, Lachlan and Murrumbidgee catchments. The Cobar Peneplain Bioregion lies in central NSW west of the Great Dividing Range. It is one of only two of the state’s bioregions to occur entirely within the state, the other being the Sydney Basin Bioregion. The bioregion extends 2. Climate from just south of Bourke to north of Griffith, has a total area of 7,334,664 ha, The Cobar Peneplain is one of 6 bioregions that lie in Australia’s hot, and occupies 9.2% of the state. The bioregion is bounded to the north and persistently dry semi-arid climatic zone. This climate is complemented by east by the Darling Riverine Plains Bioregion, to the east by the South Western patches of sub-humid climate on the southeastern boundary of the Slopes Bioregion, and by the Riverina and Murray Darling Depression bioregion and, in the south, these areas are characterised by virtually no dry Bioregions to the south and west. The northwestern part of the Cobar season and a hot summer (Stern et al. 2000). Peneplain Bioregion falls in the Western Division. Throughout the year, average evaporation exceeds the average rainfall. The Cobar Peneplain Bioregion encompasses the townships of Cobar, Rainfall tends to be summer dominant in the north of the bioregion and Nymagee, Byrock, Girilambone, Lake Cargelligo and Rankins Springs with winter dominant in the south (Creaser and Knight 1996, Smart et al. 2000a). Louth and Tottenham lying at its boundary. Temperatures are typically mild in winter and hot in summer and exceed 40°C In the north of the bioregion, Yanda Creek, a major stream, discharges directly for short periods during December to February (Creaser and Knight 1996). -

BOOKBINDING .;'Ft1'

• BALOS BOOKBINDING .;'fT1'. I '::1 1 I't ABORIGINAL SONGS FROM THE BUNDJALUNG AND GIDABAL AREAS OF SOUTH-EASTERN AUSTRALIA by MARGARET JANE GUMMOW A thesis submitted in fulfihnent ofthe requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department ofMusic University of Sydney July 1992 (0661 - v£6T) MOWWnO UllOI U:lpH JO .uOW:lW :lip Ol p:ll1l:>W:l<J ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Firstly, I wish to express my most sincere thanks to all Bundjalung and Gidabal people who have assisted this project Many have patiently listened to recordings ofold songs from the Austra1ian Institute ofAboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, sung their own songs, translated, told stories from their past, referred me to other people, and so on. Their enthusiasm and sense ofurgency in the project has been a continual source of inspiration. There are many other people who have contributed to this thesis. My supervisor, Dr. Allan Marett, has been instrumental in the compilation of this work. I wish to thank him for his guidance and contributions. I am also indebted to Dr. Linda Barwick who acted as co-supervisor during part of the latter stage of my candidature. I wish to thank her for her advice on organising the material and assistance with some song texts. Dr. Ray Keogh meticulously proofread the entire penultimate draft. I wish to thank him for his suggestions and support. Research was funded by a Commonwealth Postgraduate Research Award. Field research was funded by the Austra1ian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. Several staff members at AlATSIS have been extremely helpful. -

Areference Grammar of Gamilaraay, Northern New

A REFERENCE GRAMMAR OF GAMILARAAY, NORTHERN NEW SOUTH WALES Peter Austin Department of Linguistics La Trobe University Bundoora. Victoria 3083 Australia first draft: 29th March 1989 this draft: 8th September 1993 2 © Peter K. Austin 1993 THIS BOOK IS COPYRIGHT. DO NOT QUOTE OR REPRODUCE WITHOUT PERMISSION Preface The Gamilaraay people (or Kamilaroi as the name is more commonly spelled) have been known and studied for over one hundred and sixty years, but as yet no detailed account of their language has been available. As we shall see, many things have been written about the language but until recently most of the available data originated from interested amateurs. This description takes into account all the older materials, as well as the more recent data. This book is intended as a descriptive reference grammar of the Gamilaraay language of north-central New South Wales. My major aim has been to be as detailed and complete as possible within the limits imposed by the available source materials. In many places I have had to rely heavily on old data and to ‘reconstitute’ structures and grammatical patterns. Where possible I have included comparative notes on the closely related Yuwaalaraay and Yuwaaliyaay languages, described by Corinne Williams, as well as comments on patterns of similarity to and difference from the more distantly related Ngiyampaa language, especially the variety called Wangaaypuwan, described by Tamsin Donaldson. As a companion volume to this grammar I plan to write a practically-oriented description intended for use by individuals and communities in northern New South Wales. This practical description will be entitled Gamilaraay, an Aboriginal Language of Northern New South Wales. -

FROM SPEAKING NGIYAMPAA to SPEAKING ENGLISH Tamsin

FROM SPEAKING NGIYAMPAA TO SPEAKING ENGLISH Tamsin Donaldson This paper1 is both background and sequel to ‘What’s in a name? An etymological view of land, language and social identification from central western New South Wales.’2 That paper’s first part looked at traditional Ngiyampaa social nomenclature, and its second part ‘at changes in the ways in which people of Ngiyampaa descent perceive their social world, changes . which have taken place alongside their changeover from speaking Ngiyampaa to speaking English’. Here I outline the causes of the changeover and discuss some of its symptoms. Similar transitions have been or are being made all over Australia. It is now likely that less than a quarter of the two hundred odd discrete Australian languages known to have been spoken in the past are still being acquired by children. These children are also learning English, at the very least to the extent that educational policy is implemented. What does the future hold? Which elements in the linguistic history of the people of Ngiyampaa descent are likely to be repeated in communities whose languages are being as universally spoken now as Ngiyampaa was, at least in the southwest of Ngiyampaa territory, for a hundred years or so after the first intrusions of English speakers?3 (By ‘universally’ I mean ‘right through’, as the usual Aboriginal phrase goes, by all generations.) I shall be concentrating on the twentieth-century linguistic experiences of a group of Ngiyampaa speakers from this southwest corner, from the dry belar and nelia tree country north of Willandra Creek and south of Cobar and Sandy or Crowl Creek — see Map — and on those of their descendants. -

Skin, Kin and Clan: the Dynamics of Social Categories in Indigenous

Skin, Kin and Clan THE DYNAMICS OF SOCIAL CATEGORIES IN INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIA Skin, Kin and Clan THE DYNAMICS OF SOCIAL CATEGORIES IN INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIA EDITED BY PATRICK MCCONVELL, PIERS KELLY AND SÉBASTIEN LACRAMPE Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia ISBN(s): 9781760461638 (print) 9781760461645 (eBook) This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover image Gija Kinship by Shirley Purdie. This edition © 2018 ANU Press Contents List of Figures . vii List of Tables . xi About the Cover . xv Contributors . xvii 1 . Introduction: Revisiting Aboriginal Social Organisation . 1 Patrick McConvell 2 . Evolving Perspectives on Aboriginal Social Organisation: From Mutual Misrecognition to the Kinship Renaissance . 21 Piers Kelly and Patrick McConvell PART I People and Place 3 . Systems in Geography or Geography of Systems? Attempts to Represent Spatial Distributions of Australian Social Organisation . .43 Laurent Dousset 4 . The Sources of Confusion over Social and Territorial Organisation in Western Victoria . .. 85 Raymond Madden 5 . Disputation, Kinship and Land Tenure in Western Arnhem Land . 107 Mark Harvey PART II Social Categories and Their History 6 . Moiety Names in South-Eastern Australia: Distribution and Reconstructed History . 139 Harold Koch, Luise Hercus and Piers Kelly 7 . -

A Linguistic Bibliography of Aboriginal Australia and the Torres Strait Islands

OZBIB: a linguistic bibliography of Aboriginal Australia and the Torres Strait Islands Dedicated to speakers of the languages of Aboriginal Australia and the Torres Strait Islands and al/ who work to preserve these languages Carrington, L. and Triffitt, G. OZBIB: A linguistic bibliography of Aboriginal Australia and the Torres Strait Islands. D-92, x + 292 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1999. DOI:10.15144/PL-D92.cover ©1999 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. PACIFIC LINGUISTICS FOUNDING EDITOR: Stephen A. Wurm EDITORIAL BOARD: Malcolm D. Ross and Darrell T. Tryon (Managing Editors), John Bowden, Thomas E. Dutton, Andrew K. Pawley Pacific Linguistics is a publisher specialising in linguistic descriptions, dictionaries, atlases and other material on languages of the Pacific, the Philippines, Indonesia and Southeast Asia. The authors and editors of Pacific Linguistics publications are drawn from a wide range of institutions around the world. Pacific Linguistics is associated with the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies at The Australian NatIonal University. Pacific Linguistics was established in 1963 through an initial grant from the Hunter Douglas Fund. It is a non-profit-making body financed largely from the sales of its books to libraries and individuals throughout the world, with some assistance from the School. The Editorial Board of Pacific Linguistics is made up of the academic staff of the School's Department of Linguistics. The Board also appoints a body of editorial advisors drawn from the international community of linguists. -

Wailwan Education Notes

POWERHOUSE MUSEUM SharingSharing aa WailwanWailwan storystory EDUCATION KIT Sharing a Wailwan story EDUCATION KIT Written by Steve Miller, Education officer, Aboriginal projects, Powerhouse Museum with additional material from Tamsin Donaldson, Joe Flick, Brad Steadman and Ann Stephen a touring exhibition from the Powerhouse Museum, Sydney Published in conjunction with the exhibition Sharing a Wailwan story, a touring exhibition from the Powerhouse Museum, Sydney. Developed and produced by the Powerhouse Museum. Written by Steve Miller, education officer, Aboriginal projects, Education and Visitor Services Additional material Tamsin Donaldson, Joe Flick, Brad Steadman and Ann Stephen, curator, Social History Cover art direction by Rea, an artist of Wailwan/Gamilaroi descent through her maternal grandfather, Harold Leslie. Artwork by Catherine Dunn, Print Media Editing and project coordination by Julie Donaldson and Kirsten Tilgals, Print Media Desktop publishing by Anne Slam, Print Media © 1999 Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences (Powerhouse Museum), Sydney The Powerhouse Museum, part of the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, also incorporating Sydney Observatory, is a NSW government cultural institution. Powerhouse Museum 500 Harris Street Ultimo Sydney NSW PO Box K346 Haymarket NSW 1238 telephone (02) 9217 0213 www.phm.gov.au This document is also available on the Powerhouse Museum website www.phm.gov.au Important notes The exhibition and this education kit contain photos and names of Aboriginal people who have passed away. All material used is with the consent of Wailwan elders. To avoid causing offence or distress, teachers and exhibitors are asked to draw the attention of all other Aboriginal people to this information prior to viewing the material. -

Wiradjuri Dubbo College St Program

Stage 4 Unit of Work Aboriginal Language(s): Wiradjuri School: Dubbo College Term: 1 Unit: 4.2 Year: 2009 Theme / Focus: Country Indicative time: 25 hours (25 x 60-minute lessons) per term. 6 lessons per fortnight. Unit Description Focus and contributing outcomes for the unit Learning in this unit focuses on developing students’ understanding 4.UL.1 demonstrates understanding of the main ideas and supporting detail in spoken texts and responds of Wiradjuri knowledge of country and connections between the appropriately people and the river, culminating in an excursion to the river with 4.UL.2 demonstrates understanding of the main ideas and supporting detail in written texts and responds Elders and other community members. This theme includes appropriately language learning experiences and spoken and written texts related 4.UL.3 establishes and maintains communication in familiar situations to: relationships between language groups in western NSW, 4.UL.4 experiments with linguistic patterns and structures in Aboriginal languages to convey information and to mapping country, placenames, directions, and seasonal relationships express own ideas effectively between country, climate, flora and fauna. Students acquire 4.MLC.1 demonstrates understanding of the importance of correct and appropriate use of language in diverse vocabulary, expressions and language structures within this context. contexts A focus of the unit will be the story of the journey of Gaygaa along 4.MLC.2 explores the diverse ways in which meaning is conveyed by comparing and describing structures and the river and the connections between Wiradjuri and other features of Aboriginal languages Aboriginal language groups. 4.MBC.1 demonstrates understanding of the interdependence of language and culture 4.MBC.2 demonstrates knowledge of the cultures of Aboriginal communities Language structures Key new vocabulary • Suffixes for location and position, e.g. -

Water Management Plan 2020-21

Commonwealth Environmental Water Office Water Management Plan 2020–21 Acknowledgement of the Traditional Owners of the Murray–Darling Basin The Commonwealth Environmental Water Office respectfully acknowledges the Traditional Owners, their Elders past and present, their Nations of the Murray–Darling Basin, and their cultural, social, environmental, spiritual and economic connection to their lands and waters. © Copyright Commonwealth of Australia, 2020. Commonwealth Environmental Water Office Water Management Plan 2020-21 is licensed by the Commonwealth of Australia for use under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence with the exception of the Coat of Arms of the Commonwealth of Australia, the logo of the agency responsible for publishing the report, content supplied by third parties, and any images depicting people. For licence conditions see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ This report should be attributed as ‘Commonwealth Environmental Water Office Water Management Plan 2020-21, Commonwealth of Australia, 2020’. The Commonwealth of Australia has made all reasonable efforts to identify content supplied by third parties using the following format ‘© Copyright’ noting the third party. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian Government or the Minister for the Environment. While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Commonwealth does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly by, or reliance on, the contents of this publication. -

The AIATSIS Map of Indigenous Australia, List of Alternative Spellings

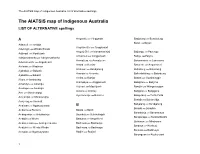

The AIATSIS map of Indigenous Australia, list of alternative spellings The AIATSIS map of Indigenous Australia LIST OF ALTERNATIVE spellings A Angardie see Yinggarda Badjulung see Bundjalung Baiali see Bayali Adawuli see Iwaidja Angkamuthi see Anggamudi Adetingiti see Winda Winda Angutj Giri see Marramaninjsji Baijungu see Payungu Adjinadi see Mpalitjanh Ankamuti see Anggamudi Bailgu see Palyku Adnjamathanha see Adnyamathanha Anmatjera see Anmatyerre Bakanambia see Lamalama Adumakwithi see Anguthimri Araba see Kurtjar Bakwithi see Anguthimri Airiman see Wagiman Arakwal see Bundjalung Balladong see Balardung Ajabakan see Bakanh Aranda see Arrernte Ballerdokking see Balardung Ajabatha see Bakanh Areba see Kurtjar Banbai see Gumbainggir Alura see Jaminjung Atampaya see Anggamudi Bandjima see Banjima Amandyo see Amangu Atjinuri see Mpalitjanh Bandjin see Wargamaygan Amangoo see Amangu Awara see Warray Bangalla see Banggarla Ami see Maranunggu Ayerrerenge see Bularnu Bangerang see Yorta Yorta Amijangal see Maranunggu Banidja see Bukurnidja Amurrag see Amarak Banjalang see Bundjalung Anaiwan see Nganyaywana B Barada see Baradha Anbarra see Burarra Baada see Bardi Baranbinja see Barranbinya Andagirinja see Antakarinja Baanbay see Gumbainggir Baraparapa see Baraba Baraba Andajin see Worla Baatjana see Anguthimri Barbaram see Mbabaram Andakerebina see Andegerebenha Badimaia see Badimaya Bardaya see Konbudj Andyinit see Winda Winda Badimara see Badimaya Barmaia see Badimaya Anewan see Nganyaywana Badjiri see Budjari Barunguan see Kuuku-yani 1 The -

Aboriginal History Journal: Volume 9

Aboriginal History Volume nine 1985 ABORIGINAL HISTORY INCORPORATED THE EDITORIAL BOARD Committee of Management: Stephen Foster (Chairman), Peter Grimshaw (Treasurer/Public Officer), May McKenzie (Secretary), Diane Bell, Tom Dutton, Niel Gunson, Isabel McBryde, Luise Hercus, Isobel White. Board Members: Gordon Briscoe, David Horton, Hank Nelson, Judith Wilson. ABORIGINAL HISTORY 1985 Editors: Tom Dutton, Luise Hercus. Review Editor: Isabel McBryde. CORRESPONDENTS Jeremy Beckett, Ann Curthoys, Eve Fesl, Fay Gale, Ron Lampert, Andrew Markus, John Mulvaney, Peter Read, Robert Reece, Henry Reynolds, Shirley Andrews Rosser, Charles Rowley, Lyndall Ryan, Tom Stannage, Robert Tonkinson, James Urry. Aboriginal History aims to present articles and information in the field of Australian ethno- history, particularly in the post-contact history of the Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders. Historical studies based on anthropological, archaeological, linguistic and sociological research, including comparative studies of other ethnic groups such as Pacific Islanders in Australia, will be welcomed. Future issues will include recorded oral traditions and biographies, verna cular narratives with translations, previously unpublished manuscript accounts, resumes of current events, archival and bibliographical articles, and book reviews. Aboriginal History is administered by an Editorial Board which is responsible for all unsigned material in the journal. Views and opinions expressed by the authors of signed articles and reviews are not necessarily shared by Board members. The editors invite contributions for consideration; reviews will be commissioned by the review editor. Contributions, correspondence and inquiries about subscriptions should be sent to: The Editors, Aboriginal History, C/- Department of Pacific and Southeast Asian History, Australian National University, G.P.O. Box 4, Canberra, A.C.T. -

Indigenous Languages Programmes In

Indigenous Languages Programmes in Australian Schools: A Way Forward Nola Purdie, Tracey Frigo Clare Ozolins, Geoff Noblett Nick Thieberger, Janet Thieberger, Nick Geoff Noblett Frigo Clare Ozolins, Tracey Forward Nola Purdie, Way A Australian Schools: Indigenous Languages Programmes in Indigenous Languages Programmes in Australian Schools A Way Forward Nola Purdie, Tracey Frigo Clare Ozolins, Geoff Noblett Nick Thieberger, Janet Sharp Indigenous Languages Programmes in Australian Schools A Way Forward Nola Purdie, Tracey Frigo Clare Ozolins, Geoff Noblett Nick Thieberger, Janet Sharp Australian Council for Educational Research This project was funded by the former Australian Government Department of Education, Science and Training through the Australian Government’s School Languages Programme. The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Australian Government Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations. © Commonwealth of Australia 2008 This work is copyright. It may be reproduced in whole or in part for study or for training purposes subject to the inclusion of an acknowledgement of the source and no commercial usage or sale. Reproduction for purposes other than those indicated above requires the prior written permission from the Commonwealth. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to Commonwealth Copyright Administration, Attorney General's Department, Robert Garran Offices, National Circuit, Barton ACT 2600 or posted at http://www.ag.gov.au/cca. Front cover artwork by Betty Bolton, Year 4 student at Moorditj Noongar Community College. Western Australia. ISBN 978-0-86431-842-8 Map of Aboriginal Australia David R Horton, creator, © Aboriginal Studies Press, AIATSIS and Auslig/Sinclair, Knight, Merz, 1996.