'Dublin's North Inner City, Preservationism and Irish Modernity in the 1960S'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PHOENIX PARK TRANSPORT and MOBILITY OPTIONS STUDY Public Consultation Brochure | January 2021 PROJECT DESCRIPTION the PREFERRED OPTION

PHOENIX PARK TRANSPORT AND MOBILITY OPTIONS STUDY Public Consultation Brochure | January 2021 PROJECT DESCRIPTION THE PREFERRED OPTION The Office of Public Works with the National The Phoenix Park Transport and Mobility J Traffic will be reduced on the North Road and Transport Authority, Dublin City Council Options Report makes a number of key the Upper Glen Road so as to improve the and Fingal County Council, at a request recommendations including the following: amenities in these areas. In the medium to long of Minister of State at the Office of Public term, vehicular restriction will be introduced at Works, developed a framework to help J Prioritise pedestrian infrastructure Cabra, Ashtown and Knockmaroon Gates. shape and inform a vision for how visitors including the upgrade of over 7km of will access, experience and move within the footpaths along with strategic pedestrian J In the short to medium term a bus service will be Phoenix Park while protecting its character crossing points on Chesterfield Avenue and introduced for Dublin Zoo and the Phoenix Park and biodiversity, and thus enhancing the other key locations throughout the Park, Visitor Centre, serving all areas along this route overall visitor experience. including the Gate entrances. and linking to Heuston Station and Broombridge Luas Station. J Expand and upgrade the cycle network The Report is based on a set of core within the Park and linkages to the external J The speed limit will be set at 30kph with a review Movement Principles; that the Park is for networks to facilitate all cycling users. This of parking and byelaws being recommended. -

Stage 2: from Celbridge to Lyons Estate

ARTHUR’S WAY, CELBRIDGE Arthur’s Way is a heritage trail across northeast County Kildare that follows in the footsteps of Arthur Guinness. In just 16 km, it links many of the historic sites associated with Ireland’s most famous brewers – the Guinness family. Visitors are invited to explore Celbridge - where Arthur STAGE 2: FROM CELBRIDGE TO LYONS ESTATE spent his childhood, Leixlip - the site of his first brewery and Oughterard graveyard - Arthur’s final resting place near his ancestral home. The trail rises gently from the confluence of the Liffey and Rye rivers at Leixlip to the Palladian Castletown House estate and onto Celbridge. INTRODUCTION It then departs the Liffey Valley to join the Grand Canal at Hazelhatch. elbridge (in Irish Cill Droichid ) means ‘church by the The Manor Mills (or Celbridge Mill) was built by Louisa Conolly The grassy towpaths guide visitors past beautiful flora and fauna and the bridge’. Originally, the Anglicised form would have been in 1785-8, and was reputedly the largest woollen mills in Ireland enchanting Lyons Estate. At Ardclough, the route finally turns for Castletown House written as Kildrought, and this version of the name still in the early 1800s. It has been restored recently. Oughterard which offers spectacular views over Kildare, Dublin and the gate lodge survives in some parts of the town. There is a rich history in this Province of Leinster. designed by English area dating back 5,000 years, with many sites of interest. Local residents have developed an historical walking route which garden designer R o y MAYNOOTH a l C St. -

UCD Commuting Guide

University College Dublin An Coláiste Ollscoile, Baile Átha Cliath CAMPUS COMMUTING GUIDE Belfield 2015/16 Commuting Check your by Bus (see overleaf for Belfield bus map) UCD Real Time Passenger Information Displays Route to ArrivED • N11 bus stop • Internal campus bus stops • Outside UCD James Joyce Library Campus • In UCD O’Brien Centre for Science Arriving autumn ‘15 using • Outside UCD Student Centre Increased UCD Services Public ArrivED • UCD now designated a terminus for x route buses (direct buses at peak times) • Increased services on 17, 142 and 145 routes serving the campus Transport • UCD-DART shuttle bus to Sydney Parade during term time Arriving autumn ‘15 • UCD-LUAS shuttle bus to Windy Arbour on the LUAS Green Line during Transport for Ireland term time Transport for Ireland (www.transportforireland.ie) Dublin Bus Commuter App helps you plan journeys, door-to-door, anywhere in ArrivED Ireland, using public transport and/or walking. • Download Dublin Bus Live app for updates on arriving buses Hit the Road Don’t forget UCD operates a Taxsaver Travel Pass Scheme for staff commuting by Bus, Dart, LUAS and Rail. Hit the Road (www.hittheroad.ie) shows you how to get between any two points in Dublin City, using a smart Visit www.ucd.ie/hr for details. combination of Dublin Bus, LUAS and DART routes. Commuting Commuting by Bike/on Foot by Car Improvements to UCD Cycling & Walking Facilities Parking is limited on campus and available on a first come first served basis exclusively for persons with business in UCD. Arrived All car parks are designated either permit parking or hourly paid. -

Draft Fingal County Development Plan 2017-2023

DRAFT FINGAL COUNTY DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2017-2023 SUBMISSION RELATING TO FORMER PHOENIX PARK RACECOURSE & ADJOINING LANDS, CASTLEKNOCK, DUBLIN 15 PART A: FORMER RACECOURSE - LANDS SOUTH OF THE N3 PART B: RAILWAY SITE - LANDS NORTH OF THE N3 On behalf of: FLYNN & O’FLAHERTY CONSTRUCTION April 2016 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Purpose of Submission On behalf of Flynn & O’Flaherty Construction (hereafter F&OF) the following submission to the proposed Draft Fingal County Development Plan 2017-2023 is made in respect of the former Phoenix Park Racecourse and adjoining lands, Castleknock, Dublin 15. The purpose of the current submission is to identify the policies and objectives of the Draft Fingal Development Plan that relate to the F&FO’F lands at the former Phoenix Park Racecourse and north of the N3 and to suggest “Amendments” that will facilitate the ongoing development of the lands over period 2017-2023 and beyond. 1.2 Lands Subject of this Submission Figure 1 identifies the location and extent of the F&OF lands. The overall F&OF land holding comprises 42.8ha. The F&O’F lands are described in detail within Section 2.0 to 4.0 below. However, for clarity and to reflect their very different planning considerations, this submission divides the lands into two parts as follows: - PART A: Former Phoenix Park Racecourse – Lands south of the N3 - 37.9ha. PART B: Railway Site – Lands north of the N3 – 4.9ha. (This area is part of the lands referred to in the Draft Development Plan as the “Navan Road Parkway” Local Area Plan lands). -

66 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

66 bus time schedule & line map 66 Merrion Square South - Kingsbury Estate View In Website Mode The 66 bus line (Merrion Square South - Kingsbury Estate) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Merrion Square South - Kingsbury Estate: 6:00 AM - 11:15 PM (2) Straffan Road (Kingsbury Estate) - Merrion Square South: 5:45 AM - 11:15 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 66 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 66 bus arriving. Direction: Merrion Square South - Kingsbury 66 bus Time Schedule Estate Merrion Square South - Kingsbury Estate Route 60 stops Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 7:05 AM - 11:05 PM Monday 6:00 AM - 11:15 PM Merrion Sq South, Stop 7391 Merrion Square South, Dublin Tuesday 6:00 AM - 11:15 PM Holles Street, Stop 493 Wednesday 6:00 AM - 11:15 PM 27 Merrion Square North, Dublin Thursday 6:00 AM - 11:15 PM Clare Street Friday 6:00 AM - 11:15 PM 20 Clare Street, Dublin Saturday 6:15 AM - 11:15 PM Pearse Station, Stop 495 Westland Row, Dublin Shaw Street, Stop 400 194 Pearse Street, Dublin 66 bus Info Direction: Merrion Square South - Kingsbury Estate Pearse St Garda Stn, Stop 346 Stops: 60 17 Botany Bay, Dublin Trip Duration: 68 min Line Summary: Merrion Sq South, Stop 7391, Holles Westmoreland Street Street, Stop 493, Clare Street, Pearse Station, Stop 28 Westmoreland Street, Dublin 495, Shaw Street, Stop 400, Pearse St Garda Stn, Stop 346, Westmoreland Street, Temple Bar, Temple Bar, Wellington Quay Wellington Quay, Merchant's Quay, Stop 1444, 11 Essex Street East, Dublin Usher's -

Customer Service Poster

Improved Route 747 Airlink Express [ Airport ➔ City ] Dublin 2 Terminal 1 International Heuston Terminal 2 Exit road The O Convention Commons Street Talbot Street Gardiner Street Lower Cathal Brugha Street O’Connell Street College Green Christchurch Ushers Quay Dublin Airport Financial Rail Station Dublin Airport Dublin Airport Centre Dublin & Central Bus Station & O'Connell St. Upper & Temple Bar Cathedral Services Centre 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Luas Maldron Hotel Jurys Inn Busáras Maple Hotel The Gresham Hotel Wynns Hotel The Westin Hotel Jurys Inn Christchurch Maldron Hotel, Heuston Central Bus Station Rail Station Red Line Cardiff Lane Custom House Abbot Lodge Academy Plaza Hotel Abbey Court Hostel Barnacles Hostel The Arlington Hotel Smithfield Connolly Rail Station Luas Red line Gibson Hotel Clarion Guesthouse Cassidy's Hotel The Arlington Hotel Blooms Hotel Temple Bar Ellis Quay Apartments IFSC Hotel Luas Red line Ashling Hotel Abraham House Jurys Inn Parnell Street Bachelors Walk The Trinity Capitol Harding Hotel The Four Courts Hostel North Star Hotel Hostel Litton Lane Hostel Kinlay House O'Sheas Merchant The Hilton Lynams Hotel Temple Bar Hotel Kilmainham Airlink Timetable Hotel Isaacs Amberley House The Morrison Hotel Paramount Hotel Park Inn Smithfield Maldron Hotel The Times Hostel Phoenix Park Isaacs Hostel Browns Hotel Parnell Square Clifton Court Hotel The Parliament Hotel Generator Hostel Brooks Hotel Faireld Ave Guesthouse Airlink 747 A irport City Centre Heuston Station Jacobs Inn Dergvale Hotel Smithfield -

The Phoenix Park Visitor Guide

Recreation Beautiful vistas of the Dublin Mountains, tree lined paths, wildflower meadows, Phoenix Park Phoenix Park - A National Historic Park Over 2,300 sporting events take place in the lakeside and woodland walks are just some Phoenix Park in the intensive recreation of the many opportunities to enjoy in the The Phoenix Park at 707 hectares is one of the largest enclosed zone every year. They are organised by park. Parks within any European City. accredited sporting organisations to train VISITOR’S GUIDE and play matches such as soccer, gaelic Biodiversity SIGNIFICANT PARK DATES football, hurling and camogie.There are also General demesne of Kilmainham Priory south of the many athletic events. About 30% of the Phoenix Park is covered c.1177 Hugh Tyrell 1st Baron of Castleknock, granted River Liffey, but with the building of the A wide range of recreational activities by trees, which are mainly broadleaf The Phoenix Park at 707 hectares is one Royal Hospital at Kilmainham, which including orienteering, astronomy, cross land, including what is now Phoenix Park land, parkland species such as oak, ash, lime, of the largest enclosed recreational spaces (commenced in 1680), the Park was country events, athletics, cycle races and beech, sycamore and horsechestnut. A to the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem at within any European capital city. It is larger reduced to its present size, all of which is model aeroplane flying are organised by more ornamental selection of trees is Kilmainham. than all of London’s city parks put together, now North of the river Liffey. In 1747 the various clubs and groups who use the park. -

Appendix 5.4.3 – RMP Sites Within the Surrounding Area

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT REPORT PARNELL SQUARE CULTURAL QUARTER Appendix 5.4.3 – RMP Sites within the Surrounding Area RMP No.: DU018-024 Street naMe: Hardwicke Lane Ward: Rotunda Ward Classification: Well Dist. from c. 170m north-northeast development: Description: No information in file. Reference: SMR File RMP No.: DU018-425 Street naMe: Parnell Street Ward: Rotunda Ward Classification: Monumental structure Dist. from c. 270m southeast development: Description: The following account of this monument is derived from the report on the ‘History of monuments. O’Connell Street area’ commissioned by Dublin City Council in 2003 (SMR file): ‘Sackville Street was also to be the location for one of the last sculptural initiatives in the city before independence when, in 1899, the foundation stone was laid for a monument dedicated to Charles Stewart Parnell (1846- 1891). On 3 January 1882 a resolution was passed by Dublin City Council to grant the freedom of the city to Parnell. Later that year, on 15 August 1882 Parnell arrived at the unveiling ceremony for the O’Connell Monument accompanying the archbishop in his ceremonial carriage. A scene which would seem unlikely as subsequent events in Parnell’s personal life unfolded. The plan for the Parnell monument was instigated by John Redmond (who succeeded Parnell as leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party) partly as a symbolic gesture to honour the ‘uncrowned king of Ireland’ and to consolidate his aspiration to reunite the constitutionalists under his own leadership. The monument would be funded through the efforts of a voluntary body, the Parnell Committee founded in 1898. The committee was chaired by Lord Mayor Daniel Tallon, other members were Count Plunkett, Dr. -

Welcome to UCD Dear Student, It Is a Great Pleasure to Welcome You to University College Dublin

Welcome to UCD Dear Student, It is a great pleasure to welcome you to University College Dublin. As an international university, UCD offers many learning opportunities both inside and outside the lecture theatre. It is our sincere hope that you will be able to take full advantage of these, and become involved in the dynamic life of our University. The staff of the UCD International Office are here to provide you with the necessary support that you may require and will help you minimise any disruptions you may experience. If you need help, you should not hesitate to ask for our assistance. We are also pleased to welcome you to Dublin. Take time to experience the city’s vibrant life and culture – be sure to explore this cosmopolitan European city and the multitude of activities on offer. You will find that the more you seek, the more you will discover. Finally, we hope that this practical handbook will help you to get to know more about life in UCD and Dublin. Please read it and keep it for future reference during your stay. Its aim is to provide you with practical information about life as a new international student at UCD and as a new member of the wider Dublin community. CONTACT DETAILS: International Office Reception Tierney Building UCD, Belfield, Dublin 4, Ireland Tel: +353 1 716 1701 This booklet is produced for information only. Every effort is made to ensure that Fax: +353 1 716 1165/1071 it is accurate at time of going to print. Email: [email protected] However, the University is not bound by Website: www.ucd.ie/international any error or omission therein. -

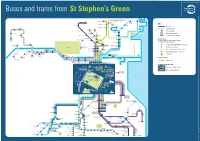

Buses and Trams from St Stephen's Green

142 Buses and trams from St Stephen’s Green 142 continues to Waterside, Seabury, Malahide, 32x continues to 41x Broomfield, Hazelbrook, Sainthelens and 15 Portmarnock, Swords Manor Portmarnock Sand’s Hotel Baldoyle Malahide and 142 Poppintree 140 Clongriffin Seabury Barrysparks Finglas IKEA KEY Charlestown SWORDS Main Street Ellenfield Park Darndale Beaumont Bus route Fosterstown (Boroimhe) Collinstown 14 Coolock North Blakestown (Intel) 11 44 Whitehall Bull Tram (Luas) line Wadelai Park Larkhill Island Finglas Road Collins Avenue Principal stop Donnycarney St Anne’s Park 7b Bus route terminus Maynooth Ballymun and Gardens (DCU) Easton Glasnevin Cemetery Whitehall Marino Tram (Luas) line terminus Glasnevin Dublin (Mobhi) Harbour Maynooth St Patrick’s Fairview Transfer Points (Kingsbury) Prussia Street 66x Phibsboro Locations where it is possible to change Drumcondra North Strand to a different form of transport Leixlip Mountjoy Square Rail (DART, COMMUTER or Intercity) Salesian College 7b 7d 46e Mater Connolly/ 67x Phoenix Park Busáras (Infirmary Road Tram (Luas Red line) Phoenix Park and Zoo) 46a Parnell Square 116 Lucan Road Gardiner Bus coach (regional or intercity) (Liffey Valley) Palmerstown Street Backweston O’Connell Street Lucan Village Esker Hill Abbey Street Park & Ride (larger car parks) Lower Ballyoulster North Wall/Beckett Bridge Ferry Port Lucan Chapelizod (142 Outbound stop only) Dodsboro Bypass Dublin Port Aghards 25x Islandbridge Heuston Celbridge Points of Interest Grand Canal Dock 15a 15b 145 Public Park Heuston Arran/Usher’s -

Irish Marriages, Being an Index to the Marriages in Walker's Hibernian

— .3-rfeb Marriages _ BBING AN' INDEX TO THE MARRIAGES IN Walker's Hibernian Magazine 1771 to 1812 WITH AN APPENDIX From the Notes cf Sir Arthur Vicars, f.s.a., Ulster King of Arms, of the Births, Marriages, and Deaths in the Anthologia Hibernica, 1793 and 1794 HENRY FARRAR VOL. II, K 7, and Appendix. ISSUED TO SUBSCRIBERS BY PHILLIMORE & CO., 36, ESSEX STREET, LONDON, [897. www.genespdf.com www.genespdf.com 1729519 3nK* ^ 3 n0# (Tfiarriages 177.1—1812. www.genespdf.com www.genespdf.com Seventy-five Copies only of this work printed, of u Inch this No. liS O&CLA^CV www.genespdf.com www.genespdf.com 1 INDEX TO THE IRISH MARRIAGES Walker's Hibernian Magazine, 1 771 —-1812. Kane, Lt.-col., Waterford Militia = Morgan, Miss, s. of Col., of Bircligrove, Glamorganshire Dec. 181 636 ,, Clair, Jiggmont, co.Cavan = Scott, Mrs., r. of Capt., d. of Mr, Sampson, of co. Fermanagh Aug. 17S5 448 ,, Mary = McKee, Francis 1S04 192 ,, Lt.-col. Nathan, late of 14th Foot = Nesbit, Miss, s. of Matt., of Derrycarr, co. Leitrim Dec. 1802 764 Kathcrens, Miss=He\vison, Henry 1772 112 Kavanagh, Miss = Archbold, Jas. 17S2 504 „ Miss = Cloney, Mr. 1772 336 ,, Catherine = Lannegan, Jas. 1777 704 ,, Catherine = Kavanagh, Edm. 1782 16S ,, Edmund, BalIincolon = Kavanagh, Cath., both of co. Carlow Alar. 1782 168 ,, Patrick = Nowlan, Miss May 1791 480 ,, Rhd., Mountjoy Sq. = Archbold, Miss, Usher's Quay Jan. 1S05 62 Kavenagh, Miss = Kavena"gh, Arthur 17S6 616 ,, Arthur, Coolnamarra, co. Carlow = Kavenagh, Miss, d. of Felix Nov. 17S6 616 Kaye, John Lyster, of Grange = Grey, Lady Amelia, y. -

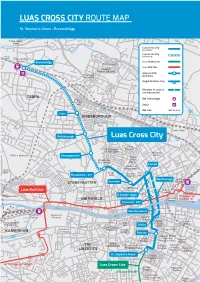

LUAS CROSS CITY ROUTE MAP Luas Cross City I

LUAS CROSS CITY ROUTE MAP Luas Cross City i St. Stephen’s Green - Broombridge GLASNEVIN Tolka Valley Park Luas Cross City (on street) Luas Cross City Royal (off street) Canal Broombridge Station Broombridge Luas Green Line Rose Garden Luas Red Line National Botanic Gardens Stops in both Glasnevin directions DRUMCONDRA Cemetery Griffith Park Single direction stop Direction of Luas on one way section Tolka Park CABRA Mount Rail Interchange Bernard Park Depot Royal Canal Rail Line Tolka River Cabra PHIBSBOROUGH Dalymount Park Croke Park Phibsborough Luas Cross City Royal Canal Mater Blessington Hospital Street Basin Mountjoy McKee Barracks Grangegorman Square Hugh Broadstone Lane Bus Garage Gallery Parnell Garden of Remembrance Dublin Zoo Kings Rotunda The Broadstone - DIT Inns Hospital Gate Marlborough Connolly STONEYBATTER Dominick Station Ilac Shopping Luas Red Line Centre Abbey Theatre O’Connell Upper GPO Phoenix Park To Docklands/ Custom The Point SMITHFIELD House O’Connell - GPO IFSC Liffey Westmoreland Heuston Guinness Liffey Station Brewery Bank of Ireland Civic Trinity Science Royal Hospital Offices City Trinity College Gallery Kilmainham Hall Dublin NCAD Christ Church Guinness Cathedral Dublin College Park KILMAINHAM Storehouse Castle Dawson Camac Leinster House River Gaiety Houses of National Theatre the Oireachtas Gallery Saint THE Patrick's Park Stephen’s Green National Natural Shopping Center Museum History Merrion LIBERTIES Museum Square Fatima St. Stephen’s Green Saint Stephen's Green To Saggart/Tallaght Luas Green Line Iveagh Fitzwilliam Gardens Square To Brides Glen National Concert Hall Wilton Park DOLPHIN’S BARN PORTOBELLO Dartmouth Square Kevins GAA Club 5-10 O3 11-13 EXTENT OF APPROVED RAILWAY ORDER REF.