And After a Continentalist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Challenge of African Art Music Le Défi De La Musique Savante Africaine Kofi Agawu

Document généré le 30 sept. 2021 18:33 Circuit Musiques contemporaines The Challenge of African Art Music Le défi de la musique savante africaine Kofi Agawu Musiciens sans frontières Résumé de l'article Volume 21, numéro 2, 2011 Cet article livre des réflexions générales sur quelques défis auxquels les compositeurs africains de musique de concert sont confrontés. Le point de URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1005272ar départ spécifique se trouve dans une anthologie qui date de 2009, Piano Music DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1005272ar of Africa and the African Diaspora, rassemblée par le pianiste et chercheur ghanéen William Chapman Nyaho et publiée par Oxford University Press. Aller au sommaire du numéro L’anthologie offre une grande panoplie de réalisations artistiques dans un genre qui est moins associé à l’Afrique que la musique « populaire » urbaine ou la musique « traditionnelle » d’origine précoloniale. En notant les avantages méthodologiques d’une approche qui se base sur des compositions Éditeur(s) individuelles plutôt que sur l’ethnographie, l’auteur note l’importance des Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal rencontres de Steve Reich et György Ligeti avec des répertoires africains divers. Puis, se penchant sur un choix de pièces tirées de l’anthologie, l’article rend compte de l’héritage multiple du compositeur africain et la façon dont cet ISSN héritage influence ses choix de sons, rythmes et phraséologie. Des extraits 1183-1693 (imprimé) d’oeuvres de Nketia, Uzoigwe, Euba, Labi et Osman servent d’illustrations à cet 1488-9692 (numérique) article. Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Agawu, K. -

Afrofuturism: the World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture

AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISM Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 1 5/22/13 3:53 PM Copyright © 2013 by Ytasha L. Womack All rights reserved First edition Published by Lawrence Hill Books, an imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Womack, Ytasha. Afrofuturism : the world of black sci-fi and fantasy culture / Ytasha L. Womack. — First edition. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 (trade paper) 1. Science fiction—Social aspects. 2. African Americans—Race identity. 3. Science fiction films—Influence. 4. Futurologists. 5. African diaspora— Social conditions. I. Title. PN3433.5.W66 2013 809.3’8762093529—dc23 2013025755 Cover art and design: “Ioe Ostara” by John Jennings Cover layout: Jonathan Hahn Interior design: PerfecType, Nashville, TN Interior art: John Jennings and James Marshall (p. 187) Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 I dedicate this book to Dr. Johnnie Colemon, the first Afrofuturist to inspire my journey. I dedicate this book to the legions of thinkers and futurists who envision a loving world. CONTENTS Acknowledgments .................................................................. ix Introduction ............................................................................ 1 1 Evolution of a Space Cadet ................................................ 3 2 A Human Fairy Tale Named Black .................................. -

1 Chapter Three Historical

University of Pretoria etd, Adeogun A O (2006) CHAPTER THREE HISTORICAL-CULTURAL BACKCLOTH OF MUSIC EDUCATION IN NIGERIA This chapter traces the developments of music education in the precolonial Nigeria. It is aimed at giving a social, cultural and historical background of the country – Nigeria in the context of music education. It describes the indigenous African music education system that has been in existence for centuries before the arrival of Islam and Christianity - two important religions, which have influenced Nigerian music education in no small measure. Although the title of this thesis indicates 1842-2001, it is deemed expedient, for the purposes of historical background, especially in the northern part of Nigeria, to dwell contextually on the earlier history of Islamic conquest of the Hausaland, which introduced the dominant musical traditions and education that are often mistaken to be indigenous Hausa/northern Nigeria. The Islamic music education system is dealt with in Chapter four. 3.0 Background - Nigeria Nigeria, the primarily focus of this study, is a modern nation situated on the Western Coast of Africa, on the shores of the Gulf of Guinea which includes the Bights of Benin and Biafra (Bonny) along the Atlantic Coast. Entirely within the tropics, it lies between the latitude of 40, and 140 North and longitude 20 501 and 140 200 East of the Equator. It is bordered on the west, north (northwest and northeast) and east by the francophone countries of Benin, Niger and Chad and Cameroun respectively, and is washed by the Atlantic Ocean, in the south for about 313 kilometres. -

Wavelength (April 1981)

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies 4-1981 Wavelength (April 1981) Connie Atkinson University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength Recommended Citation Wavelength (April 1981) 6 https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength/6 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wavelength by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. APRIL 1 981 VOLUME 1 NUMBE'J8. OLE MAN THE RIVER'S LAKE THEATRE APRIL New Orleans Mandeville, La. 6 7 8 9 10 11 T,HE THE THIRD PALACE SUCK'S DIMENSION SOUTH PAW SALOON ROCK N' ROLL Baton Rouge, La. Shreveport. La. New Orleans Lalaye"e, La. 13 14 15 16 17 18 THE OLE MAN SPECTRUM RIVER'S ThibOdaux, La. New Orleans 20 21 22 23 24 25 THE LAST CLUB THIRD HAMMOND PERFORMANCE SAINT DIMENSION SOCIAL CLUB OLE MAN CRt STOPHER'S Baton Rouge, La. Hammond, La. RIVER'S New Orleans New Orleans 27 29 30 1 2 WEST COAST TOUR BEGINS Barry Mendelson presents Features Whalls Success? __________________6 In Concert Jimmy Cliff ____________________., Kid Thomas 12 Deacon John 15 ~ Disc Wars 18 Fri. April 3 Jazz Fest Schedule ---------------~3 6 Pe~er, Paul Departments April "Mary 4 ....-~- ~ 2 Rock 5 Rhylhm & Blues ___________________ 7 Rare Records 8 ~~ 9 ~k~ 1 Las/ Page _ 8 Cover illustration by Rick Spain ......,, Polrick Berry. Edllor, Connie Atkinson. -

Lost Wax: an Exploration of Bronze Sculpture in Senegal Kevin Bell SIT Study Abroad

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2009 Lost Wax: An Exploration of Bronze Sculpture in Senegal Kevin Bell SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Art Practice Commons Recommended Citation Bell, Kevin, "Lost Wax: An Exploration of Bronze Sculpture in Senegal" (2009). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 735. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/735 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lost Wax: An Exploration of Bronze Sculpture in Senegal Bell, Kevin Academic Director: Diallo, Souleye Project Advisor: Diop, Issa University of Denver International Studies Africa, Senegal, Dakar Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Senegal Arts and Culture, SIT Study Abroad, Fall 2009 Table of Contents ABSTRACT: ................................................................................................................................................................1 I. LEARNING GOALS: .........................................................................................................................................2 I. RESOURCES AND METHODS: ......................................................................................................................3 -

Five Takes on African Art a Study Guide

FIVE TAKES ON AFRICAN ART A STUDY GUIDE TAKE 1 considers materiality, and the elements used to make aesthetic objects. It also considers the connections that materials have to the people who originally crafted them, and furthermore, their ties to new generations of crafters, interpreters, and collectors of African works. The objects in this collection challenge our notions of “African art” in that they were not formed for purely aesthetic purposes, but rather were created from raw, natural materials, carefully refined, and then skillfully handcrafted to serve particular needs in homes and communities. It is fascinating to consider that each object featured here bears a characteristic that identifies it as belonging to a distinct region or group of people, and yet is nearly impossible to unearth the narratives of the individual artists who created them. Through these works, we can consider the bridge between materiality and diaspora—objects of significance with “genetic codes” that move from one hand to the next, across borders, and oceans, with a dynamism that is defined by our ever-shifting world. Here, these “useful” objects take on a new function, as individual parts to an entire chorus of voices—each possessing a unique story in its creation and journey. What makes these objects ‘collectors’ items’? Pay close attention to the shapes, forms, and craftsmanship. Can you find common traits or themes? The curator talks about their ‘genetic codes’. Beside the object’s substance, specific to the location of its creation, it may carry traces of other accumulated materials, such as food, skin, fiber, or fluids. -

OJAI at BERKELEY VIJAY IYER, Music DIRECTOR

OJAI AT BERKELEY VIJAY IYER, MusIC DIRECTOR The four programs presented in Berkeley this month mark the seventh year of artistic partnership between the Ojai Music Festival and Cal Performances and represent the combined efforts of two great arts organizations committed to innovative and adventur- ous programming. The New York Times observes, “There’s prob- ably no frame wide enough to encompass the creative output of the pianist Vijay Iyer.” Iyer has released 20 albums covering remarkably diverse terrain, most recently for the ECM label. The latest include A Cosmic Rhythm with Each Stroke (2016), a collaboration with Iyer’s “hero, friend, and teacher,” Wadada Leo smith; Break Stuff (2015), featuring the Vijay Iyer Trio; Mutations (2014), featuring Iyer’s music for piano, string quartet, and electronics; and RADHE RADHE: Rites of Holi (2014), the score to a film by Prashant Bhargava, performed with the renowned International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE). The Vijay Iyer Trio (Iyer, stephan Crump on bass, and Marcus Gilmore on drums) made its name with two acclaimed and influential albums. Acceler ando (2012) was named Jazz Album of the Year in three separate critics polls, by the Los Angeles Times, Amazon.com, and NPR. Hailed by PopMatters as “the best band in jazz,” the trio was named 2015 Jazz Group of the Year in the DownBeat poll, with Vijay Iyer (music director), the Grammy- Iyer having earlier received an unprecedented nominated composer-pianist, was described “quintuple crown” in their 2012 poll (Jazz by Pitchfork as “one of the most interesting Artist of the Year, Pianist of the Year, Jazz and vital young pianists in jazz today,” by the Album of the Year, Jazz Group of the Year, and LA Weekly as “a boundless and deeply impor- Rising star Composer). -

Contemporary Africa Arts

CONTEMPORARY AFRICAN ARTS MAPPING PERCEPTIONS, INSIGHTS AND UK-AFRICA COLLABORATIONS 2 CONTENTS 1. Key Findings 4 2. Foreword 6 3. Introduction 8 4. Acknowledgements 11 5. Methodology 12 6. What is contemporary African arts and culture? 14 7. How do UK audiences engage? 16 8. Essay: Old Routes, New Pathways 22 9. Case Studies: Africa Writes & Film Africa 25 10. Mapping Festivals - Africa 28 11. Mapping Festivals - UK 30 12. Essay: Contemporary Festivals in Senegal 32 13. What makes a successful collaboration? 38 14. Programming Best Practice 40 15. Essay: How to Water a Concrete Rose 42 16. Interviews 48 17. Resources 99 Cover: Africa Nouveau - Nairobi, Kenya. Credit: Wanjira Gateri. This page: Nyege Nyege Festival - Jinja, Uganda. Credit: Papashotit, commissioned by East Africa Arts. 3 1/ KEY FINDINGS We conducted surveys to find out about people’s perceptions and knowledge of contemporary African arts and culture, how they currently engage and what prevents them from engaging. The first poll was conducted by YouGov through their daily online Omnibus survey of a nationally representative sample of 2,000 adults. The second (referred to as Audience Poll) was conducted by us through an online campaign and included 308 adults, mostly London-based and from the African diaspora. The general British public has limited knowledge and awareness of contemporary African arts and culture. Evidence from YouGov & Audience Polls Conclusions Only 13% of YouGov respondents and 60% of There is a huge opportunity to programme a much Audience respondents could name a specific wider range of contemporary African arts and example of contemporary African arts and culture, culture in the UK, deepening the British public’s which aligned with the stated definition. -

Sustaining Afrocentric Spiritual Jazz in 21St Century Chicago

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2016 Sacred Freedom: Sustaining Afrocentric Spiritual Jazz in 21St Century Chicago Adam Zanolini The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1617 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] SACRED FREEDOM: SUSTAINING AFROCENTRIC SPIRITUAL JAZZ IN 21ST CENTURY CHICAGO by ADAM ZANOLINI A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 ADAM ZANOLINI All Rights Reserved ii Sacred Freedom: Sustaining Afrocentric Spiritual Jazz in 21st Century Chicago by Adam Zanolini This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Music in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _________________ __________________________________________ DATE David Grubbs Chair of Examining Committee _________________ __________________________________________ DATE Norman Carey Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: _________________ __________________________________________ DATE Jeffrey Taylor _________________ __________________________________________ DATE Fred Moten _________________ __________________________________________ DATE Michele Wallace iii ABSTRACT Sacred Freedom: Sustaining Afrocentric Spiritual Jazz in 21st Century Chicago by Adam Zanolini Advisor: Jeffrey Taylor This dissertation explores the historical and ideological headwaters of a certain form of Great Black Music that I call Afrocentric spiritual jazz in Chicago. However, that label is quickly expended as the work begins by examining the resistance of these Black musicians to any label. -

Au Echo 2021 1 Note from the Editor

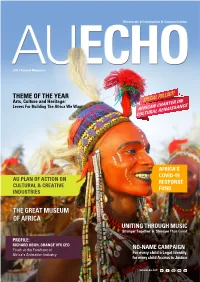

Directorate of Information & Communication 2021 Annual Magazine THEME OF THE YEAR Arts, Culture and Heritage: Levers For Building The Africa We Want AFRICAN CHARTER ON CULTURAL RENAISSANCE AFRICA’S COVID-19 AU PLAN OF ACTION ON RESPONSE CULTURAL & CREATIVE FUND INDUSTRIES THE GREAT MUSEUM OF AFRICA UNITING THROUGH MUSIC ‘Stronger Together’ & ‘Stronger Than Covid’ PROFILE: RICHARD OBOH, ORANGE VFX CEO Youth at the Forefront of NO-NAME CAMPAIGN Africa’s Animation Industry For every child a Legal Identity, for every child Access to Justice www.au.int AU ECHO 2021 1 NOTE FROM THE EDITOR he culture and creative industries (CCIs) generate annual global revenues of up to US$2,250 billion dollars and Texports in excess of US$250 billion. This sector currently provides nearly 30 million jobs worldwide and employs more people aged 15 to 29 than any other sector and contributes LESLIE RICHER up to 10% of GDP in some countries. DIRECTOR Directorate of Information & In Africa, CCIs are driving the new economy as young Africans Communication tap into their unlimited natural resource and their creativity, to create employment and generate revenue in sectors traditionally perceived as “not stable” employment options. taking charge of their destiny and supporting the initiatives to From film, theatre, music, gaming, fashion, literature and art, find African solutions for African issues. On Africa Day (25th the creative economy is gradually gaining importance as a May), the African Union in partnership with Trace TV and All sector that must be taken seriously and which at a policy level, Africa Music Awards (AFRIMA) organised a Virtual Solidarity decisions must be made to invest in, nurture, protect and grow Concert under the theme ‘Stronger Together’ and ‘Stronger the sectors. -

Pan-Africanism and the Black Festivals of Arts and Culture: Today’S Realities and Expectations

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 20, Issue 3, Ver. 1 (Mar. 2015), PP 22-28 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Pan-Africanism and the Black Festivals of Arts and Culture: Today’s Realities and Expectations Babasehinde Augustine Ademuleya (Ph. D) & Michael Olusegun Fajuyigbe (M. Phil) Department of Fine and Applied Arts, Obáfémi Awólówò University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria . Abstract: The first two editions of the Festivals of Blacks arts and culture which owed much to the ideologies of the Pan-Africanism and Negritude that preceded them, no doubt laid legacies that have continued to serve as strong reference points in the discussion of Africans and African descent relationship. Apart from providing an unusual forum that brought to light the diverse contributions of Blacks and African peoples to the universal currents of thought and arts, both editions drew attentions to the expected relationship between the continental Africans and their offspring in the Diaspora. The events reassert the African identity thus creating the platform for continental Africa and the Diaspora to move through the borders of nation state and the psychosocial borders of racism which is central to all Pan-Africanist freedom movements. It is however worrisome that forty eight years after the maiden edition of the festival (FESMAN) and thirty seven years after the second (FESTAC), the achieved cultural integration is yet to translate into much expected economical, political, educational, philosophical and technological advancements of African nations and that of the Diaspora. This paper therefore attempts a review of the Black Festivals of Arts with a view to highlighting how the achieved cultural integration through the arts could be further explored for today’s realities and expectations. -

Module 1 AFRO-LATIN AMERICAN and POPULAR MUSIC

Republic of the Philippines Department of Education Regional Office IX, Zamboanga Peninsula 10 Zest for Progress Zeal of Partnership MUSIC Quarter 2, Wk.1 - Module 1 AFRO-LATIN AMERICAN AND POPULAR MUSIC Name of Learner: ___________________________ Grade & Section: ___________________________ 0 Name of School: ___________________________ WHAT I NEED TO KNOW KkKNOW Music has always been an important part in the daily life of the African, whether for work, religion, ceremonies, or even communication. Singing, dancing, hand clapping and the beating of drums are essential to many African ceremonies, including those for birth, death, initiation, marriage, and funerals. Music and dance are also important to religious expression and political events. However, because of its wide influences on global music that has permeated contemporary American, Latin American, and European styles, there has been a growing interest in its own cultural heritage and musical sources. In this module, it contains review on the different elements of music and to analyze the characteristics of Afro-Latin American and popular music were: African music, Latin American music, Jazz music, and Popular music. Also includes the vocal forms, instruments, vocal and dance, and instrumental forms mentioned above. At the end of this module, you are expected to: 1. Analyzes musical characteristics of Afro-Latin American and popular music through listening activities. ( MU10AP-IIa-h-5) WHAT I KNOW Directions: Read and understand the questions carefully and write your answers on the blanks provided. 1. What is the overall quality of sound of a piece, most often indicated by the number/layer of voices in the music ? Answer: ________________ 2.