Dankwoord,Kyrgyzstan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Officieren Van De Militaire School

367 BIJLAGE X (SIAPA DIA, WHO'S WHO )1) Bijvoegsel 1Inlandse officieren van de militaire school. Bijvoegsel 2(Aspirant-)officieren van KMA-Breda. Bijvoegsel 3(Aspirant-)officieren van de Hoofd Cursus. Bijvoegsel 4Aspirant-officieren van KMA-Bandoeng. Bijvoegsel 5Inheemse officieren van gezondheid. Bijvoegsel 6Aspirant-officieren van het CORO. Bijvoegsel 7Aspirant-officieren van de Inheemse Militie. Bijvoegsel 8Aspirant-officieren van de ML-KNIL. Bijvoegsel 9Andere vooroorlogse en oorlogs-opleidingen. Bijvoegsel 10De opleidingen van de SROI en het OCO. Bijvoegsel 11Officieren van andere na-oorlogse opleidingen. Bijvoegsel 12De reserve-legerpendeta en -legerpredikanten. 1) De informatie in de volgende bijvoegsels is in hoofdzaak afkomstig uit stamboeken, persoonsdossiers, archiefonderzoek en interviews. 368 BIJVOEGSEL 1 BIJ BIJLAGE X: INLANDSE OFFICIEREN * naam (geboortedatum) ** in werkelijke dienst (rang bij pensioen) *** overleden vóór 17-8-'45? (overleden) [wel/niet bij skn RI] * 1. ASMINO. (11-4-1891) ** 1-7-1910 (-) *** ? [-] 10-10-1913 inlands tlnt infanterie. Geplaatst bij diverse bataljons op Java. Ontslag niet op eigen verzoek per 29-1-1917. 2. HOLLAND SOEMODILOGO, Raden Bagoes (SOENDJOJO, Raden .). (12-6-1890) 1-7-1909 (kapt) - (okt 1945) [+] 22-10-1914 inlands tlnt infanterie, 22-10-1917 inlands elnt, 31-7-1925 opgenomen in de ranglijst der Europese officieren. Onderwierp zich 11-8-1926 aan het voor Europeanen vastgestelde burgerlijk- en handelsrecht, waarbij hij de geslachtsnaam Holland Soemodilogo aannam onder toevoeging van zijn toenmalige titel Raden Bagoes . Juni 1927 aangesteld als wervingsofficier van de II e Divisie. 27-9-1927 kapt. 31-7-1935 op verzoek e.o.. Kwam als niet-reserveplichtig gepensioneerd officier bij de algemene mobilisatie weer in dienst. -

Keputusan Menteri Kesehatan Republik Indonesia Nomor: Hk.01.07/Menkes/44/2019 Tentang Tim Kesehatan Haji Indonesia Tahun 1440 H/2019 M

KEPUTUSAN MENTERI KESEHATAN REPUBLIK INDONESIA NOMOR: HK.01.07/MENKES/44/2019 TENTANG TIM KESEHATAN HAJI INDONESIA TAHUN 1440 H/2019 M DENGAN RAHMAT TUHAN YANG MAHA ESA MENTERI KESEHATAN REPUBLIK INDONESIA, Menimbang : bahwa dalam rangka pelaksanaan tugas pembinaan, pelayanan, dan perlindungan kesehatan bagi jemaah haji di kelompok terbang (kloter), perlu menetapkan Keputusan Menteri Kesehatan tentang Penetapan Tim Kesehatan Haji Indonesia Tahun 1440 H/2019 M. Mengingat : 1. Undang-Undang Nomor 29 Tahun 2004 tentang Praktik Kedokteran (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 2004 Nomor 116, Tambahan Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Nomor 4431); 2. Undang-Undang Nomor 13 Tahun 2008 tentang Penyelenggaraan Ibadah Haji (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 2008 Nomor 60, Tambahan Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Nomor 4845) sebagaimana telah diubah dengan Undang-Undang Nomor 34 Tahun 2009 tentang Penetapan Paraturan Pemerintah Pengganti Undang-Undang Nomor 2 Tahun 2009 tentang Perubahan atas - 2 - Undang-Undang Nomor 13 Tahun 2008 tentang Penyelenggaraan Ibadah Haji menjadi Undang-Undang (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 2009 Nomor 110, Tambahan Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Nomor 5036); 3. Undang-Undang Nomor 36 Tahun 2009 tentang Kesehatan (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 2009 Nomor 144, Tambahan Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Nomor 5063); 4. Undang-Undang Nomor 36 Tahun 2014 tentang Tenaga Kesehatan (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 2014 Nomor 298, Tambahan Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia -

DEMOKRASI DALAM SEJARAH MILITER INDONESIA Kajian Historis Tentang Pemilihan Panglima Tentara Pertama Pada 1945 Widyo Nugrahanto

Sosiohumaniora - Jurnal Ilmu-ilmu Sosial dan Humaniora Vol. 20, No. 1, Maret 2018: 78 - 85 ISSN 1411 - 0903 : eISSN: 2443-2660 DEMOKRASI DALAM SEJARAH MILITER INDONESIA Kajian Historis Tentang Pemilihan Panglima Tentara Pertama Pada 1945 Widyo Nugrahanto dan Rina Adyawardhina Program Studi Sejarah Fakultas Ilmu Budaya Universitas Padjadjaran E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRAK, Penelitian ini berjudul Demokrasi dalam Sejarah Militer Indonesia; Kajian Historis Tentang Pemilihan Panglima Tentara Pertama pada 1945. Penelitian ini adalah tentang bagaimana Soedirman terpilih sebagai Panglima Tentara Indonesia yang pertama. Begitu juga bagaimana cara pemilihannya sehingga Soedirman terpilih dan Oerip Soemohardjo terpilih mendampinginya sebagai kepala staf. Metode penelitian yang digunakan adalah metode sejarah. Metode Sejarah terdiri dari empat tahapan, yaitu heuristik, kritik, interpretasi, dan historiografi. Sumber-sumber penelitian ini menggunakan koran-koran sezaman, majalah sezaman, buku, dan jurnal. Kesimpulan penelitian ini menunjukkan bahwa terpilihnya Soedirman (Panglima Tentara) dan Oerip Soemohardjo (kepala Staf Tentara) merupakan cara-cara demokrasi langsung yang dilaksanakan pertama kali setelah Indonesia meredeka. Uniknya adalah cara ini justru digunakan oleh tentara dalam pemilihan panglima tertingginya. Kata kunci: Panglima, TNI, Demokrasi. DEMOCRACY IN INDONESIAN MILITARY HISTORY Historical Study about the Election of the First Army Commander in 1945 ABSTRACT, The main subject this study is election the first commander of Indonesia’s Military. In this case, Soedirman chose as Military Commander and Oerip Soemohardjo as Chief of Staff. Study emlpoys a Historical Method, which consists of four stage: Heuristic, Critic, Interpretation, Historiography. The study utilize some sources such as newspaper, magazine, book, and journal. Main finding of this study are the election applied a direct democratic system. -

The 1St ASMIHA Digital Conference 23‐25 October 2020 Abstracts

Indonesian Journal of Cardiology Indonesian J Cardiol 2020:41:suppl_A pISSN: 0126-3773 / eISSN: 2620-4762 doi: 10.30701/ijc.1075 The 1st ASMIHA Digital Conference 23‐25 October 2020 Abstracts: Case Reports Indonesian Journal of Cardiology Indonesian J Cardiol 2020:41:suppl_A pISSN: 0126-3773 / eISSN: 2620-4762 doi: 10.30701/ijc.1075 1. Challenging Case of Cardiac Arrest due to Pure Inferior STEMI with Bad Comorbidities: A Case Report I. Sabrina1, M. R. Felani2, I. A. Siregar3 1Faculty of Medicine, Trisakti University, Jakarta, Indonesia; 2Department of Cardiology and Vascular Medicine, University of Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia; 3Departement of Cardiology, Dr. Mintohardjo Naval Hospital, Jakarta, Indonesia Background: Cardiac arrest is the worst complication that can occur in ACS. Myocardial infarction causes conductivity disturbances of myocardial electric potential, thus often triggered malignant arrhythmias lead to cardiac arrest. However, malignant arrhythmias are not always present in all types of ACS, depends on the infarction areas, so that patient with pure STEMI inferior rarely presents with malignant arrhythmias caused by ACS itself. Case illustration:65‐Year‐Old patient presented into ER with worsening squeezing chest pain since 5 hours before admission. He had any similar complaint before and ever refused to get CAG previously. He had uncontrolled hypertension and Type‐2 DM. On physical examination, we obtained BP 125/70 mmHg, HR 72 bpm, RR 20 x/min, afebrile, and SpO2 98%, crackles (+), with normal in other general physical examination. 12‐lead ECG showed pure Inferior STEMI, no Posterior or RV involvement. Echocardiography showed LVEF 45% and diastolic dysfunction, RMWA (+), and moderate MR. -

Tesis Analisis Kinerja Rumah Sakit Umum Daerah Dengan

TESIS ANALISIS KINERJA RUMAH SAKIT UMUM DAERAH DENGAN MENGGUNAKAN BALANCE SCORECARD (STUDI KASUS PADA RSUD Dr. SOEGIRI LAMONGAN) Diajukan Oleh: ZAKARIA ANSHORI 16440019 PROGRAM STUDI MAGISTER AKUNTANSI FAKULTAS EKONOMI DAN BISNIS UNIVERSITAS WIJAYA KUSUMA SURABAYA 2018 TESIS ANALISIS KINERJA RUMAH SAKIT UMUM DAERAH DENGAN MENGGUNAKAN BALANCE SCORECARD (STUDI KASUS PADA RSUD Dr. SOEGIRI LAMONGAN) TESIS Untuk memperoleh Gelar Magister Dalam Program Studi Magister Akuntansi Pada Fakultas Ekonomi dan Bisnis Universitas Wijaya Kusuma Surabaya Oleh: ZAKARIA ANSHORI 16440019 PROGRAM STUDI MAGISTER AKUNTANSI FAKULTAS EKONOMI DAN BISNIS UNIVERSITAS WIJAYA KUSUMA SURABAYA 2018 ii ANALISIS KINERJA RUMAH SAKIT UMUM DAERAH DENGAN MENGGUNAKAN BALANCE SCORECARD (STUDI KASUS PADA RSUD Dr. SOEGIRI LAMONGAN) “Untuk memperoleh Gelar Magister dalam Program Studi Magister Akuntansi Universitas Wijaya Kusuma Surabaya” Tanggal 16 Agustus 2018 Oleh: ZAKARIA ANSHORI 16440019 PROGRAM STUDI MAGISTER AKUNTANSI FAKULTAS EKONOMI DAN BISNIS UNIVERSITAS WIJAYA KUSUMA SURABAYA 2018 iii Lembar Pengesahan TESIS TELAE DISETUJUI TANGGAL 14 AGUSTTIS 2OI8 Pembimbing i Pembitrtbing II '--'W^*- Dr. Trntri Bararoh, Sll, U.Si. Nl. tk Drs. Ec. Ru i Pratono, Ali, MM, CA, CMPA Mengetahui Ketua Progam Studi Magister Al<untansi Iakultas Ekonomi dan Bisnis Univercitas Wijaya Kusuma Surabaya Dr. l'antri BaIaroh, Sla, \l.Si, M.,\h iv Tesis ini telah diuji dan dinilai Oleh panitia penguji pada Progam Pascasat'ana Universitas Wiiaya Kusurna Surabaya Pada tanggal 16 Agustus 2018 Panitia Pengrji . Ir, Ismanto IIadi S., M.Si Anggota ,VL\L I Lilik Pirmaningsih, Ak, M.Ak, CA I)r's. llc. Rutli o, IM, Ak, CA Tosis ini telah ditedma sebagai salah sat[ persyaratan Untuk memperoleh gela. Magiste. -

Han Bing Siong Captain Huyer and the Massive Japanese Arms Transfer in East Java in October 1945

Han Bing Siong Captain Huyer and the massive Japanese arms transfer in East Java in October 1945 In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 159 (2003), no: 2/3, Leiden, 291-350 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com10/07/2021 03:57:08AM via free access HAN BING SIONG Captain Huyer and the massive Japanese arms transfer in East Java in October 1945 The interested layman surveying the historiography of Indonesia in the period immediately following the surrender of Japan will soon be struck by the obvious anti-Japanese bias of most Dutch historians (for examples see Han Bing Siong 1996,1998, 2000, and 2001b). Many of them interpret the part played by the Japanese in events in the post-surrender period negatively, as being antagonistic to the Dutch and supportive of the Indonesian cause. And where the Japanese did fight against the Indonesians and protected the Dutch, these authors often trivialize the Japanese actions and describe them as being too hesitant and ill-timed, as being inspired by concern for their own safety or by vindictiveness, or as following on direct orders from the Allied authorities. A few exceptions aside - such as the diaries or memoirs of H.E. Keizer-Heuzeveldt (1982:77), J. van Baal (1985:368, 1989:512), and G. Boissevain and L. van Empel (1991:305), and several other contemporary publications - there is a noticeable reluctance to acknowledge that Dutch people in some cases in fact owed their lives to the Japanese.1 This is curious, as many of these Dutch historians belong to a younger generation or have 1 According to Wehl (1948:41) the situation in Bandung especially was very dangerous for the Dutch. -

Bab 2 Perkembangan Fungsi Pembinaan Teritorial Satuan Komando Kewilayahan Tni Ad

BAB 2 PERKEMBANGAN FUNGSI PEMBINAAN TERITORIAL SATUAN KOMANDO KEWILAYAHAN TNI AD Bab 2 ini membahas perkembangan pelaksanaan fungsi pembinaan teritorial Satuan Kowil TNI AD dari tahun 1945 hingga tahun 2009. Pembahasan fungsi pembinaan teritorial Satuan Kowil TNI AD mencakup: (1) fungsi pembinaan teritorial sebagai perwujudan dari strategi perang semesta (total war); (2) fungsi pembinaan teritorial sebagai strategi pengelolaan potensi nasional; (3) fungsi pembinaan teritorial sebagai strategi penjaga stabilitas politik dan keamanan pemerintahan Orde Baru; (4) fungsi pembinaan teritorial sebagai pemberdayaan wilayah pertahanan di darat dan kekuatan pendukungnya secara dini untuk mendukung sistem pertahanan dan sistem pelawanan rakyat semesta. Pembahasan dimulai dari fungsi teritorial militer Belanda (KNIL) tahun 1830-1942 dan perang gerilya militer Jepang (PETA/Heiho) tahun 1942-1945 untuk melihat “benang merah” keterkaitan dengan pembentukan fungsi Satuan Kowil TNI AD. Sedangkan pelaksanaan fungsi pembinaan teritorial Satuan Kowil TNI AD dari masing-masing tahap pembentukannya sejak Komanden TKR hingga Satuan Kowil TNI AD dan konflik internal militer yang menyertainya merupakan inti pembahasan dari Sub-Bab 2 ini. 2.1. Komando Teritorial KNIL Koninklijk Nederlandsch Indische Leger (KNIL) merupakan badan militer resmi Kerajaan Belanda yang dibentuk pada tahun 1830 di Hindia Belanda.161 Tujuan pembentukan badan militer ini adalah untuk melaksanakan dua fungsi sekaligus (dwifungsi), yaitu: (1) fungsi militer untuk menjaga Hindia Belanda dari 161 Koninklijk Nederlands Indisch Leger (KNIL) yang terbentuk pada 10 Maret 1830 adalah nama resmi Tentara Kerajaan Hindia-Belanda. Meskipun KNIL militer pemerintahan Hindia Belanda, tapi banyak para anggotanya merupakan penduduk pribumi. Di antara perwira yang memegang peranan penting dalam pengembangan dan kepemimpinan angkatan bersenjata Indonesia yang pernah rnenjadi anggota KNIL pada saat rnenjelang kemerdekaan adalah Oerip Soemohardjo, E. -

Daftar Nama Rumah Sakit Rujukan Penanggulangan Infeksi Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-2019) Sesuai Keputusan Menteri Kesehatan RI

Daftar Nama Rumah Sakit Rujukan Penanggulangan Infeksi Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-2019) Sesuai Keputusan Menteri Kesehatan RI Nama RS Alamat Nanggroe Aceh Darussalam RSU Dr. Zainoel Abidin Jl. Tgk. Daud Beurueh No. 108 1. Banda Aceh Banda Aceh Telp : 651-22077, 28148 RSU Cut Meutia Jl. Banda Aceh-Medan Km.6 Buket Rata 2. Lhokseumawe Lhokseumawe Telp : 0645-43012 Sumatera Utara RSU H. Adam Malik Jl. Bunga Lau No. 17 3. Medan Telp : 061-8360381 ; Fax : 061-8360255 Jl. KS Ketaren 8 Kabanjahe 4. RSU Kabanjahe Tlp : 0628-20550 Jl. Sutomo No. 230 P. Siantar 5. RSU Pematang Siantar Telp : 0634-21780 Jl. Bin Harun Said Tarutung 6. RSU Tarutung Telp : 0633-21303 Jl. Dr FL Tobing Pd Sidempuan 7. RSU Padang Sidempuan Telp : 0634-21780 Sumatera Barat RSU Dr. M. Jamil Jl. Perintis Kemerdekaan, Padang 8. Padang Telp : 0751-32372 Jl. Dr A. Rivai Bukit Tinggi 9. RSU Dr. Achmad Modchtar Telp : 0752-21720 Riau RSU Arifin Ahmad Jl. Diponegoro No. 2, Pekan Baru 10. Pekan Baru Telp : 0761-21618 RSU M. Sani Jl. Poros No. 1 Tg. Balai Karimun 11. Kab. Karimun Telp : 0777-327808 ; Fax : 0777-29611 Nama RS Alamat Jl. Sudirman No. 795, Tanjung Pinang 12. RSU Tanjung Pinang Telp : 0771- 21163 Jl. Veteran No. 52, Hilir Tembilahan 13. RSU Puri Husada Telp : 0768-22118 Jl. Tanjung Jati No. 4 Dumai 14. RSU Dumai Telp : 0762-38368 Kepulauan Riau Jl. Dr. Ciptomangunkusumo, Sekupang Batam 15. RS Otorita Batam Telp : 0778-322121 Jambi Jl. Letjend. Soeprapto No. 31 Telanaipura Jambi 16. RSU Raden Mattaher Jambi Telp : 0741-61692 Palembang RSU Dr. -

Edisi Khusus 2017 2

1 MAJALAH KIPRAH Vol 86 th XVII | Edisi Khusus 2017 2 MAJALAH KIPRAH Vol 86 th XVII | Edisi Khusus 2017 NUANSA 3 BAKTI PUPR BANGUN DAYA SAING BANGSA REDAKSI KIPRAH AHUN ini, 17 Agustus 2017, 72 tahun negeri ini, Indonesia, merdeka. Di tahun ini pula, Kementerian Pekerjaan Umum dan Perumahan Rakyat (PUPR) genap 72 tahun mengabdi untuk negara. Sejarah mencatat Tbanyak torehan peristiwa dan capaian yang sudah dilalui warga PUPR. Dari ikut berjuang membela negara di awal kemerdekaan, yang mana salah satunya berpuncak pada peristiwa 3 desember, saat 7 orang sapta taruna gugur mempertahankan Gedung Sate, hingga pembangunan berbagai infrastruktur hingga kini. Dengan itu, pada edisi kali ini, KIPRAH hadir khusus untuk menengok lintasan sejarah panjang pengabdian PUPR untuk negeri. Dibuka dengan pembahasan terkait awal mula berdirinya Kementerian PU yang sempat berulang kali berganti nama dan struktur organisasi, hingga kini, di era Pemerintahan Kabinet Kerja Presiden Joko Widodo, Kementerian Pekerjaan Umum dengan Kementerian Perumahan Rakyat bergabung menjadi Kementerian Pekerjaan Umum dan Perumahan Rakyat (PUPR). Untuk mengenang dan mendekatkan pembaca, KIPRAH mengulas terkait profil setiap Menteri PU yang telah menjabat, dari era awal kemerdekaan yaitu Abikoesno Tjokrosoejoso hingga era Kabinet Kerja, dimana Basuki Hadimuljono menjabat sebagai Menteri PUPR. Bukan hanya pengulasan profil, KIPRAH pun turut menghadirkan beberapa sejarah proyek-proyek besar yang telah berhasil dibangun dan menjadi salah satu dari sekian banyak pencapaian di bidang infrastruktur pada masanya. Ulasan ini dihadirkan setelah pengulasan profil Menteri terkait proyek tersebut. Hadir pula wawancara eksklusif KIPRAH dengan empat tokoh penting terkait kinerja dan harapannya untuk pemerintahan kali ini. Keempat tokoh tersebut, ialah Danang Parikesit, Guru Besar Universitas Gajah Mada (UGM) - Ketua dan Pendiri Yayasan Nusa Patris Infrastruktur “Pekerjaan 90 Persen Bagus, Tinggal Tunggu Manfaatnya”, M. -

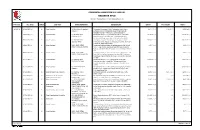

Register Sp2d

PEMERINTAH KABUPATEN BOJONEGORO REGISTER SP2D Periode : 15-Desember-2016 s/d 19-Desember-2016 TANGGAL NO. SP2D JENIS SUB UNIT NAMA PENERIMA KETERANGAN BRUTO POTONGAN NETTO 15/12/2016 6695/LS-BJ/2016 LS Dinas Kesehatan CV Adya Putra ( Drs Bambang Pembayaran Pengawasan Teknik Pembangunan Fisik Polindes 32.000.000,00 4.072.727,00 27.927.273,00 Hariyono ) Kumpulrejo, setren, Ponkesdes Dk.Singget Dinas Kesehatan Kabupaten Bojonegoro Tahun 2016, sumber dana DBHM 6696/LS-BJ/2016 LS Dinas Kesehatan CV. ANUGRAH JAYA Pembayaran Termyn 100% pembangunan gedung / ruang jaga 173.646.900,00 0,00 173.646.900,00 (Subechan al arif) PONED Puskesmas Tambakrejo Kec. Tambakrejo pada Dinas Kesehatan Kab. Bojonegoro Tahun 2016, sumber dana DBHM 6697/LS-BJ/2016 LS Dinas Kesehatan CV. ANUGRAH JAYA Pembayaran Termyn 100% Pekerjaan pembangunan gedung 166.281.500,00 0,00 166.281.500,00 (Subechan Al Arif) polindes Sstren Kec. Ngasem pada Dinas Kesehatan Kab. Bojonegoro Tahun 2016, sumber dana (DBHM) 6698/LS-BJ/2016 LS Dinas Kesehatan MOKH. SALIM (BEND. Pembayaran belanja perjalanan dinas dalam daerah bulan Juni s/d 8.850.000,00 0,00 8.850.000,00 PENGEL. DINAS KESEHATAN) Juli 2016, keg. bantuan operasional kesehatan (BOK) Puskesmas Kasiman, pada DinKes Kab. Bojonegoro 2016, sumber dana DAK non Fisik 6699/LS-BJ/2016 LS Dinas Kesehatan MOKH. SALIM (BEND. Pembayaran belanja perjalanan dinas dalam daerah bulan Maret s/d 13.625.000,00 0,00 13.625.000,00 PENGEL. DINAS KESEHATAN) April 2016, keg. bantuan operasional kesehatan (BOK) Puskesmas Pungpungan, pada DinKes Kab. Bojonegoro 2016, sumber dana DAK non Fisik 6700/LS-BJ/2016 LS Dinas Kesehatan CV. -

Arnout Van Der Meer

©2014 Arnout Henricus Cornelis van der Meer ALL RIGHTS RESERVED AMBIVALENT HEGEMONY: CULTURE AND POWER IN COLONIAL JAVA, 1808-1927 by ARNOUT HENRICUS CORNELIS VAN DER MEER A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History Written under the direction of Professor Michael Adas And approved by: _________________________________" _________________________________" _________________________________" _________________________________New Brunswick, New Jersey " OCTOBER, 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Ambivalent Hegemony: Culture and Power in Colonial Java, 1808-1927 By ARNOUT HENRICUS CORNELIS VAN DER MEER Dissertation Director: Professor Michael Adas “Ambivalent Hegemony” explores the Dutch adoption and subsequent rejection of Javanese culture, in particular material culture like dress, architecture, and symbols of power, to legitimize colonial authority around the turn of the twentieth century. The Dutch established an enduring system of hegemony by encouraging cultural, social and racial mixing; in other words, by embedding themselves in Javanese culture and society. From the 1890s until the late 1920s this complex system of dominance was transformed by rapid technological innovation, evolutionary thinking, the emergence of Indonesian nationalism, and the intensification of the Dutch “civilizing” mission. This study traces the interactions between Dutch and Indonesian civil servants, officials, nationalists, journalists and novelists, to reveal how these transformations resulted in the transition from cultural hegemony based on feudal traditions and symbols to hegemony grounded in enhanced Westernization and heightened coercion. Consequently, it is argued that we need to understand the civilizing mission ideology and the process of modernization in the colonial context as part of larger cultural projects of control. -

86 Sejarah Diplomasi Roem-Roijen Dalam

SEJARAH DIPLOMASI ROEM-ROIJEN DALAM PERJUANGAN MEMPERTAHANKAN KEMERDEKAAN REPUBLIK INDONESIA TAHUN 1949 Oleh: Agus Budiman1) 1)Dosen Prodi. Pendidikan Sejarah FKIP-UNIGAL ABSTRAK Mohammad Roem dan Dr. J.H. van Roijen merupakan dua nama wakil delegasi antara Indonesia dan Belanda yang menandatangani sebuah persetujuan yang diwakili oleh KTN (Komisi Tiga Negara) diantaranya Belgia sebagai wakil dari Belanda, Australia sebagai wakil dari Indonesia, dan Amerika sebagai penengah antara keduanya. Setelah melalui perundingan yang berlarut-larut, maka akhirnya pada tanggal 7 Mei 1949 tercapai persetujuan, yang kemudian dikenal dengan nama “Roem-Royen Statements”. Pada awalnya Persetujuan Roem- Roijentersebut ternyata tidak dapatditerima begitu saja oleh sebagian besar kalangan politisi maupun petinggi militer dari kedua belah pihak (Republik Indonesia dan Belanda),keduanyasama-sama berasumsi bahwa jika menerima hasil Perundingan Roem-Roijen berartimenerima suatu kekalahan. Namun demikan, akhirnya baik pemerintah Belanda maupun pihak R.I.mau menerima hasil persetujuan tersebut.Adapun inti dari Persetujuan Roem-Roijen adalah pelaksanaan gencatan senjatadan pengembalian Pemerintahan R.I ke Ibukota Yogyakarta, disertai dengan penarikanmundur pasukan Belanda di bawah pengawasan UNCI (United Nations Commission forIndonesia).Setelah Ibukota Yogyakarta sepenuhnya dikosongkan dari pasukanBelandamaka pada tanggal 29 Juni 1949, Tentara Republik Indonesia (TRI)danPresiden,Wakil Presiden, beserta para pemimpin Republik Indonesia lainnya, kembali ke Ibukota