Part Three: the Maritime Air War Crews Were Rewarded with Time Off During Slow Periods, 'A Procedure That Was Not Common Before

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KUNGL ÖRLOGSMANNA SÄLLSKAPET N:R 5 1954 253

KUNGL ÖRLOGSMANNA SÄLLSKAPET N:r 5 1954 253 Kring några nyförvärv i Kungl. Orlogs- 111annasällskapets bibliotek Av Kommendörkapten GEORG HAFSTRöM. Bland äldre böcker, som_ under de senare åren tillförts Sällskapets bibliotek befinner sig fyra handskrivna volym_er, mottagna såsom gåva från ett sterbhus. Två av dessa här• stammar från slutet av 1700-talet och två från förra hälften av 1800-talet. De är skrivna av tvenne sjöofficerare, resp. far och son, nämligen fänriken vid amiralitetet Michael J a rislaf von Bord-. och premiärlöjtnanten vid Kungl. Maj :ts flotta J o han August von Borclc Som de inte sakna sitt in tresse vid studiet av förhållandena inom flottan under an förda tid utan fastmera bidrager att i sin mån berika vår kännedom om vissa delar av tjänsten och livet inom sjövap• net, må några ord om desamma här vara på sin plats. Först några orienterande data om herrarna von Borclc De tillhör de en gammal pommersk adelssläkt, som under svensktiden såg flera av sina söner ägna sig åt krigaryrket. Ej mindre än 6 von Borekar tillhörde sålunda armen un der Karl XII :s dagat·, samtliga dragonofficerare. Och un der m itten och senare delen av 1700-talet var 3 medlemmar av ätten officerare vid det i Siralsund garnisonerade Drott ningens livregemente. Förmodligen son till den äldste av dessa sistnämnda föd• des Michael Jarislaf von Borck 1758. Han antogs 1786 till arklintästare vid amiralitetet och utnämndes 1790 till fän• rik, P å hösten 1794 begärde han 3 års permission »för att un der sitt nuvarande vistande i England vinna all möjlig för• ~<ovr an i metiern». -

ACTION STATIONS! HMCS SACKVILLE - CANADA’S NAVAL MEMORIAL MAGAZINE VOLUME 34 - ISSUE 2 SUMMER 2015 Volume 34 - Issue 2 Summer 2015

ACTION STATIONS! HMCS SACKVILLE - CANADA’S NAVAL MEMORIAL MAGAZINE VOLUME 34 - ISSUE 2 SUMMER 2015 Volume 34 - Issue 2 Summer 2015 Editor: LCdr ret’d Pat Jessup [email protected] Action Stations! can be emailed to you and in full colour approximately 2 weeks before it will arrive Layout & Design: Tym Deal of Deal’s Graphic Design in your mailbox. If you would perfer electronic Editorial Committee: copy instead of the printed magazine, let us know. Cdr ret’d Len Canfi eld - Public Affairs LCdr ret’d Doug Thomas - Executive Director Debbie Findlay - Financial Offi cer IN THIS ISSUE: Editorial Associates: Diana Hennessy From the Executive 3 Capt (N) ret’d Bernie Derible The Chair’s Report David MacLean The Captain’s Cabin Lt(N) Blaine Carter Executive Director Report LCdr ret’d Dan Matte Richard Krehbiel Major Peter Holmes Crossed The Bar 6 Photographers: Lt(N) ret’d Ian Urquhart Cdr ret’d Bill Gard Castle Archdale Operations 9 Sandy McClearn, Smugmug: http://smcclearn.smugmug.com/ HMCS SACKVILLE 70th Anniversary of BOA events 13 PO Box 99000 Station Forces in Halifax Halifax, NS B3K 5X5 Summer phone number downtown berth: 902-429-2132 Winter phone in the Dockyard: 902-427-2837 HMCS Max Bernays 20 FOLLOW US ONLINE: Battle of the Atlantic Place 21 HMSCSACKVILLE1 Roe Skillins National Story 22 http://www.canadasnavalmemorial.ca/ HMCS St. Croix Remembered 23 OUR COVER: In April 1944, HMCS Tren- tonian joined the East Coast Membership Update 25 fi shing fl eet, when her skipper Lieutenant William Harrison ordered a single depth charge Mail Bag 26 fi red while crossing the Grand Banks. -

Seeschlachten Im Atlantik (Zusammenfassung)

Seeschlachten im Atlantik (Zusammenfassung) U-Boot-Krieg (aus Wikipedia) 07_48/U 995 vom Typ VII C/41, der meistgebauten U-Boot-Klasse im Zweiten Weltkrieg Als U-Boot-Krieg (auch "Unterseebootkrieg") werden Kampfhandlungen zur See bezeichnet, bei denen U-Boote eingesetzt werden, um feindliche Kriegs- und Frachtschiffe zu versenken. Die Bezeichnung "uneingeschränkter U-Boot-Krieg" wird verwendet, wenn Schiffe ohne vorherige Warnung angegriffen werden. Der Einsatz von U-Booten wandelte sich im Laufe der Zeit vom taktischen Blockadebrecher zum strategischen Blockademittel im Rahmen eines Handelskrieges. Nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg änderte sich die grundsätzliche Einsatzdoktrin durch die Entwicklung von Raketen tragenden Atom- U-Booten, die als Träger von Kernwaffen eine permanente Bedrohung über den maritimen Bereich hinaus darstellen. Im Gegensatz zum Ersten und Zweiten Weltkrieg fand hier keine völkerrechtliche Weiterentwicklung zum Einsatz von U-Booten statt. Der Begriff wird besonders auf den Ersten und Zweiten Weltkrieg bezogen. Hierbei sind auch völkerrechtliche Rahmenbedingungen von Bedeutung. Anfänge Während des Amerikanischen Bürgerkrieges wurden 1864 mehrere handgetriebene U-Boote gebaut. Am 17. Februar 1864 versenkte die C.S.S. H. L. Hunley durch eine Sprengladung das Kriegsschiff USS Housatonic der Nordstaaten. Es gab 5 Tote auf dem versenkten Schiff. Die Hunley gilt somit als erstes U-Boot der Welt, das ein anderes Schiff zerstört hat. Das U-Boot wurde allerdings bei dem Angriff auf die Housatonic durch die Detonation schwer beschädigt und sank, wobei auch seine achtköpfige Besatzung getötet wurde. Auftrag der Hunley war die Brechung der Blockade des Südstaatenhafens Charleston durch die Nordstaaten. Erster Weltkrieg Die technische Entwicklung der U-Boote bis zum Beginn des Ersten Weltkrieges beschreibt ein Boot, das durch Dampf-, Benzin-, Diesel- oder Petroleummaschinen über Wasser und durch batteriegetriebene Elektromotoren unter Wasser angetrieben wurde. -

Coastal Command in the Second World War

AIR POWER REVIEW VOL 21 NO 1 COASTAL COMMAND IN THE SECOND WORLD WAR By Professor John Buckley Biography: John Buckley is Professor of Military History at the University of Wolverhampton, UK. His books include The RAF and Trade Defence 1919-1945 (1995), Air Power in the Age of Total War (1999) and Monty’s Men: The British Army 1944-5 (2013). His history of the RAF (co-authored with Paul Beaver) will be published by Oxford University Press in 2018. Abstract: From 1939 to 1945 RAF Coastal Command played a crucial role in maintaining Britain’s maritime communications, thus securing the United Kingdom’s ability to wage war against the Axis powers in Europe. Its primary role was in confronting the German U-boat menace, particularly in the 1940-41 period when Britain came closest to losing the Battle of the Atlantic and with it the war. The importance of air power in the war against the U-boat was amply demonstrated when the closing of the Mid-Atlantic Air Gap in 1943 by Coastal Command aircraft effectively brought victory in the Atlantic campaign. Coastal Command also played a vital role in combating the German surface navy and, in the later stages of the war, in attacking Germany’s maritime links with Scandinavia. Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the authors concerned, not necessarily the MOD. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form without prior permission in writing from the Editor. 178 COASTAL COMMAND IN THE SECOND WORLD WAR introduction n March 2004, almost sixty years after the end of the Second World War, RAF ICoastal Command finally received its first national monument which was unveiled at Westminster Abbey as a tribute to the many casualties endured by the Command during the War. -

Conquering the Night Army Air Forces Night Fighters at War

The U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II Conquering the Night Army Air Forces Night Fighters at War PRINTER: strip in FIGURE NUMBER A-1 Shoot at 277% bleed all sides Stephen L. McFarland A Douglas P–70 takes off for a night fighter training mission, silhouetted by the setting Florida sun. 2 The U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II Conquering the Night Army Air Forces Night Fighters at War Stephen L. McFarland AIR FORCE HISTORY AND MUSEUMS PROGRAM 1998 Conquering the Night Army Air Forces Night Fighters at War The author traces the AAF’s development of aerial night fighting, in- cluding technology, training, and tactical operations in the North African, European, Pacific, and Asian theaters of war. In this effort the United States never wanted for recruits in what was, from start to finish, an all-volunteer night fighting force. Cut short the night; use some of it for the day’s business. — Seneca For combatants, a constant in warfare through the ages has been the sanctuary of night, a refuge from the terror of the day’s armed struggle. On the other hand, darkness has offered protection for operations made too dangerous by daylight. Combat has also extended into the twilight as day has seemed to provide too little time for the destruction demanded in modern mass warfare. In World War II the United States Army Air Forces (AAF) flew night- time missions to counter enemy activities under cover of darkness. Allied air forces had established air superiority over the battlefield and behind their own lines, and so Axis air forces had to exploit the night’s protection for their attacks on Allied installations. -

Bb16 Instruction

Belcher Belcher Bits BB-16: Bits Liberator GRV Dumbo Radome / Leigh Light 1/48 33 Norway Spruce Street, Stittsville, ON, Canada K2S 1P3 Phone: (613) 836-6575, e-mail: [email protected] Intended kit: Revell Monogram B-24D rine. The first installation The Coastal Command use of the long range B-24 for anti-submarine replaced the dustbin work was the beginning of the end of the U-Boat menace in the North Atlantic; retractable lower turret on it meant there was less opportunity for submarines to surface away from con- the Wellington with a voys to recharge batteries and receive radio directions. The B-24 had the range similar mount for the Leigh for the work required as well as the capacity for the load in addition to the radar Light. A later development fit, and the speed necessary for the attack. Earlier Coastal Command aircraft housed the light in a such as the Consolidated Canso (PBY) used Yagi antenna and underslung streamlined pod slung weapons which slowed the aircraft down (and they were never speedy to start under the wing. This large with) so that a depth charge attack on a surfaced submarine often turned into a pod added considerably to shooting match. the drag of the aircraft but The B-24D (or Liberator GR V in RAF service) were delivered to the the B-24 had the neces- RCAF with the ASV Mk III centimetric radar fitted in either a retractable sary power and generating radome replacing the belly turret, or the Dumbo radome below the nose green- capacity to operate the house. -

THE HANNA HERALD "AND EAST CENTRAL ALBERTA NEWS" VOLUME XXXXV — No

™W>%wr/ • •" • ' Stars in Ploy "Charlie's Aunt" THE HANNA HERALD "AND EAST CENTRAL ALBERTA NEWS" VOLUME XXXXV — No. 26 THE HANNA HERALD ond EAST CENTRAL ALBERTA NEWS — THURSDAY, MAY 1, 1958 $3.00 per year iri Canada *—7c par copy. "HOUSECLEMING" CAMPAION GETS ^viaciaj Library UPPORT FROM TOWN COlMI L ' • • PLAY CONDUCTOR COUNCIL 6IVES FINE RECEPTION "OPEN HOUSE" AT HOSPITAL ON CHANGES COMING IN MAIL SERVICE TO BOARD OF TRADE SUGGESTION; MAY 10; PUBLIC INVITED TO Important changes in local it postal services are announced this week by Post Master C. CLEAN UP" WEEK MAY 12 lo 17 GO ON TOUR OF INSTITUTION T. Grover. One of the major changes is the closing of the Extra Garbage Collection Crews Newly Remodelled Kitchen And post office on Wednesday af Offered to Residents Who Wish To Cafeteria Centre of Much Interest; ternoon, commencing May 12. Starting June 2 the Hanna- Join In Town-wide General Clean Up Auxiliary Bfg Help To Institution Warden C.N.R. train will not arrive until late in the even "A most gratifying response", wos the way delegates The annual "Open House" at Hanna Municipal Hosp ing Tuesdays, and Saturdays. from the Hanna Board of Trade described the reception from ital will be observed Saturday, May 10th. The public is in Hence there will be no mail the Town Council Monday night, when they submitted numer vited to visit the hospital and will be conducted, in groups, sorting off this train until the ous suggestions for general clean up and improvement of the his comedy duo are stars in the play "Charlie's Aunt" com- through the hospital. -

Nightfighter Rulebook

NIGHTFIGHTER 1 NIGHTFIGHTER Air Warfare in the Night Skies of World War Two RULE BOOK Design by Lee Brimmicombe-Wood © 2011 GMT Games, LLC P.O. Box 1308, Hanford, CA 93232-1308, USA www.GMTGames.com © GMTGMT Games 1109 LLC, 2011 2 NIGHTFIGHTER CONTENTS 16.0 ADVANCED FOG OF WAR 13 1.0 Introduction 3 17.0 ADVANCED Combat 13 1.1 Rules 3 17.1 Firepower 13 1.2 Players 3 17.2 Experten 13 1.3 Scenarios 3 17.3 Aircraft Destruction 13 1.4 Scale 3 17.4 Bomber Response 14 1.5 Glossary 3 18.0 Altitude ADVantage 15 2.0 COMPONENTS 4 19.0 AI Radar 15 2.1 Maps 4 19.1 AI Radar Introduction 15 2.2 Counters 4 2.3 Play Aid Screen 5 20.0 OBLIQUE GUNS 16 2.4 Dice 5 20.1 Schräge Musik 16 3.0 SETTING UP PLAY 5 21.0 HIGH AND Low Altitudes 16 3.1 Set Up the Table 5 21.1 Low Altitude Operations 16 3.2 Scenarios 5 21.2 High Altitude Operations 16 3.3 Environment 6 22.0 FLAK 16 3.4 Scenario Setup 7 23.0 RADIO Beacon BOX 17 4.0 SEQUENCE OF PLAY 7 24.0 ADVANCED Electronics 17 4.1 End of Game 7 24.1 Special AI Radar 17 5.0 FOG OF WAR 7 24.2 Warning Devices 17 5.1 Map Information 7 24.3 Navigation Radars 17 6.0 AIRCRAFT Data Charts 8 24.4 Serrate 18 24.5 Jamming 18 7.0 MOVING BOMBERS 8 7.1 Bomber Facing 8 25.0 Ground Control INTERCEPT 18 7.2 Bomber Movement 8 25.1 GCI Search 18 25.2 MEW 19 8.0 ENTERING BOMBERS 9 8.1 Entry Chits 9 26.0 NAVAL ACTIONS 19 8.2 Bomber Entry 9 26.1 Task Forces 19 26.2 Flare Droppers 19 9.0 MOVING FIGHTERS 9 26.3 Torpedo Bombers 19 9.1 Movement Points 9 9.2 Moving 9 27.0 Intruders 20 27.1 Picking Intruders 20 10.0 BASIC TALLYING 10 27.2 Intruder -

Issue 41 Easter 2015

EASTWARD RAF Butterworth & Penang Association Easter 2015 1 Issue 41 ‘Eastward ' ’’ The RAF Butterworth &Penang Association was formed on the 30th August 1996 at the Casuarina Hotel, Batu Ferringhi, Penang Island. Association officials Chairman: Tony Parrini Treasurer : Len Wood Hamethwaite 3 Fairfield Avenue Rockcliffe Grimsby Carlisle Lincs CA6 4AA DN33 3DS Tel: 01228 674553 Tel: 01472 327886 e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] Secretary: Richard Harcourt Newsletter Editor/Archivist: 7 Lightfoot Close Dave Croft Newark West Lodge Cottage Notts 3 Boynton, Bridlington NG24 2HT YO16 4XJ Tel: 01636 650281 Tel: 01262 677520 e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] RAFBPA Shop: Don Donovan 16 The Lea Leasingham Sleaford NG34 8JY Tel: 01529 419080 e-mail: [email protected] Association website: http://raf-butterworth-penang-association.co.uk Webmaster - George Gault, e-mail: [email protected] 2 Contents Chairman’s Corner 4 From the Editor 5 Harmony in Air Traffic Control 6 General RAFBPA News and Short Stories Arnot Hill War Memorial 7 WW2 Airfields Tour Project 7 60 Squadron FEAF 8 Stop Press of the Jungle 8 Far East Mosquitos 8 Masai 'invade' Butterworth 8 Short Stories H. D. Noone 9 Richard Noone 10 Wild Beasts in Malayan Skies 11 Penang Submarine Base 14 Main Stories RAAF Butterworth 16 Memories of National Service - part 3 20 As I remember it - part 3 23 1936 Imperial Airways introduced a feeder air mail service between Penang and Hong Kong starting 24 March 1936 using DH86 aircraft.1936 3 From Your Chairman Recent events in the world remind us of the fragility of the relationships we once enjoyed when we were in the Far East. -

Brooklands Aerodrome & Motor

BROOKLANDS AERODROME & MOTOR RACING CIRCUIT TIMELINE OF HERITAGE ASSETS Brooklands Heritage Partnership CONSULTATION COPY (June 2017) Radley House Partnership BROOKLANDS AERODROME & MOTOR RACING CIRCUIT TIMELINE OF HERITAGE ASSETS CONTENTS Aerodrome Road 2 The 1907 BARC Clubhouse 8 Bellman Hangar 22 The Brooklands Memorial (1957) 33 Brooklands Motoring History 36 Byfleet Banking 41 The Campbell Road Circuit (1937) 46 Extreme Weather 50 The Finishing Straight 54 Fuel Facilities 65 Members’ Hill, Test Hill & Restaurant Buildings 69 Members’ Hill Grandstands 77 The Railway Straight Hangar 79 The Stratosphere Chamber & Supersonic Wind Tunnel 82 Vickers Aviation Ltd 86 Cover Photographs: Aerial photographs over Brooklands (16 July 2014) © reproduced courtesy of Ian Haskell Brooklands Heritage Partnership CONSULTATION COPY Radley House Partnership Timelines: June 2017 Page 1 of 93 ‘AERODROME ROAD’ AT BROOKLANDS, SURREY 1904: Britain’s first tarmacadam road constructed (location?) – recorded by TRL Ltd’s Library (ref. Francis, 2001/2). June 1907: Brooklands Motor Circuit completed for Hugh & Ethel Locke King and first opened; construction work included diverting the River Wey in two places. Although the secondary use of the site as an aerodrome was not yet anticipated, the Brooklands Automobile Racing Club soon encouraged flying there by offering a £2,500 prize for the first powered flight around the Circuit by the end of 1907! February 1908: Colonel Lindsay Lloyd (Brooklands’ new Clerk of the Course) elected a member of the Aero Club of Great Britain. 29/06/1908: First known air photos of Brooklands taken from a hot air balloon – no sign of any existing route along the future Aerodrome Road (A/R) and the River Wey still meandered across the road’s future path although a footbridge(?) carried a rough track to Hollicks Farm (ref. -

Argonauta, Vol XIV, No 2 (April 1997)

ARGONAUTA The Newsletter of The Canadian Nautical Research Society Volume XIV, Number Two April 1997 ARGONAUTA Founded 1984 by Kenneth S. Mackenzie ISSN No. 0843-8544 EDITORS Michael HENNESSY Maurice SMITH MANAGING EDITOR Margaret M. GULLIVER HONORARY EDITOR Gerald E. PANTING ARGONAUTA EDITORIAL OFFICE Maritime Studies Research Unit Memorial University of Newfoundland St. John's, NF AIC 5S7 Telephones: (709) 737-2602/(709) 737-8424 FAX: (709) 737-8427 ARGONAUTA is published four times per year in January, April, July and October and is edited for the Canadian Nautical Research society within the Maritime Studies Research Unit at Memorial University of Newfoundland. THE CANADIAN NAUTICAL RESEARCH SOCIETY Executive Officers Liaison Committee President: G. Edward REED, Ottawa Chair: William GLOVER, Markdale Past President: Faye KERT, Ottawa Atlantic: David FLEMMING, Halifax Vice-President: Christon I. ARCHER, Calgary Quebec: Eileen R. MARCIL, Charlesbourg Vice-President: William R. GLOVER, London, ON Ontario: Maurice D. SMITH, Kingston Councillor: Richard GIMBLETT, Ottawa Western: Christon I. ARCHER, Calgary Councillor: Gerald JORDAN, Toronto Pacific: John MACFARLANE, Port Alberni Councillor: James PRITCHARD, Kingston Arctic: D. Richard VALPY, Yellowknife Councillor: Maurice SMITH, Kingston Secretary: Lewis R. FISCHER, St. John's Treasurer: Ann MARTIN, Ottawa CNRS MAILING ADDRESS Annual Membership including four issues of P.O. Box 55035 ARGONAUTA and four issues of The Northern 240 Sparks Street Mariner: Individuals, $35; Institutions, $60; Students, Ottawa, ON KIP IAI $25. APRIL 1997 ARGONAUTA 1 dedicated work of Bill Glover, Ann Martin and Bob Elliot - and I hope that as many members as possible, especially INTIDSISSUE those in the Maritimes, will be able to attend. -

B&W Real.Xlsx

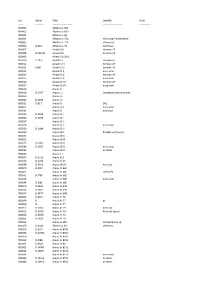

NO REGN TYPE OWNER YEAR ‐‐‐‐‐‐ ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ X00001 Albatros L‐68C X00002 Albatros L‐68D X00003 Albatros L‐69 X00004 Albatros L‐72C Hamburg Fremdenblatt X00005 Albatros L‐72C striped c/s X00006 D‐961 Albatros L‐73 Lufthansa X00007 Aviatik B.II German AF X00008 B.558/15 Aviatik B.II German AF X00009 Aviatik PG.20/2 X00010 C.1952 Aviatik C.I German AF X00011 Aviatik C.III German AF X00012 6306 Aviatik C.IX German AF X00013 Aviatik D.II nose view X00014 Aviatik D.III German AF X00015 Aviatik D.III nose view X00016 Aviatik D.VII German AF X00017 Aviatik D.VII nose view X00018 Arado J.1 X00019 D‐1707 Arado L.1 Ostseebad Warnemunde X00020 Arado L.II X00021 D‐1874 Arado L.II X00022 D‐817 Arado S.I DVL X00023 Arado S.IA nose view X00024 Arado S.I modified X00025 D‐1204 Arado SC.I X00026 D‐1192 Arado SC.I X00027 Arado SC.Ii X00028 Arado SC.II nose view X00029 D‐1984 Arado SC.II X00030 Arado SD.1 floatplane @ (poor) X00031 Arado SD.II X00032 Arado SD.III X00033 D‐1905 Arado SSD.I X00034 D‐1905 Arado SSD.I nose view X00035 Arado SSD.I on floats X00036 Arado V.I X00037 D‐1412 Arado W.2 X00038 D‐2994 Arado Ar.66 X00039 D‐IGAX Arado AR.66 Air to Air X00040 D‐IZOF Arado Ar.66C X00041 Arado Ar.68E Luftwaffe X00042 D‐ITEP Arado Ar.68E X00043 Arado Ar.68E nose view X00044 D‐IKIN Arado Ar.68F X00045 D‐2822 Arado Ar.69A X00046 D‐2827 Arado Ar.69B X00047 D‐EPYT Arado Ar.69B X00048 D‐IRAS Arado Ar.76 X00049 D‐ Arado Ar.77 @ X00050 D‐ Arado Ar.77 X00051 D‐EDCG Arado Ar.79 Air to Air X00052 D‐EHCR