(Self-)Censorship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revisiting Zero Hour 1945

REVISITING ZERO-HOUR 1945 THE EMERGENCE OF POSTWAR GERMAN CULTURE edited by STEPHEN BROCKMANN FRANK TROMMLER VOLUME 1 American Institute for Contemporary German Studies The Johns Hopkins University REVISITING ZERO-HOUR 1945 THE EMERGENCE OF POSTWAR GERMAN CULTURE edited by STEPHEN BROCKMANN FRANK TROMMLER HUMANITIES PROGRAM REPORT VOLUME 1 The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies. ©1996 by the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies ISBN 0-941441-15-1 This Humanities Program Volume is made possible by the Harry & Helen Gray Humanities Program. Additional copies are available for $5.00 to cover postage and handling from the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies, Suite 420, 1400 16th Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036-2217. Telephone 202/332-9312, Fax 202/265- 9531, E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.aicgs.org ii F O R E W O R D Since its inception, AICGS has incorporated the study of German literature and culture as a part of its mandate to help provide a comprehensive understanding of contemporary Germany. The nature of Germany’s past and present requires nothing less than an interdisciplinary approach to the analysis of German society and culture. Within its research and public affairs programs, the analysis of Germany’s intellectual and cultural traditions and debates has always been central to the Institute’s work. At the time the Berlin Wall was about to fall, the Institute was awarded a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to help create an endowment for its humanities programs. -

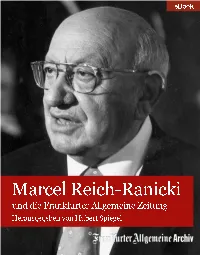

Marcel Reich-Ranicki

eBook Marcel Reich-Ranicki und die Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung Herausgegeben von Hubert Spiegel Marcel Reich-Ranicki und die Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung Herausgegeben von Hubert Spiegel F.A.Z.-eBook 21 Frankfurter Allgemeine Archiv Projektleitung: Franz-Josef Gasterich Produktionssteuerung: Christine Pfeiffer-Piechotta Redaktion und Gestaltung: Hans Peter Trötscher eBook-Produktion: rombach digitale manufaktur, Freiburg Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Rechteerwerb: [email protected] © 2013 F.A.Z. GmbH, Frankfurt am Main. Titelgestaltung: Hans Peter Trötscher. Foto: F.A.Z.-Foto / Barbara Klemm ISBN: 978-3-89843-232-0 Inhalt Ein sehr großer Mann 7 Marcel Reich-Ranicki ist tot – Von Frank Schirrmacher ..... 8 Ein Leben – Von Claudius Seidl .................... 16 Trauerfeier für Reich-Ranicki – Von Hubert Spiegel ...... 20 Persönlichkeitsbildung 25 Ein Tag in meinem Leben – Von Marcel Reich-Ranicki .... 26 Wie ein kleiner Setzer in Polen über Adolf Hitler trium- phierte – Das Gespräch führten Stefan Aust und Frank Schirrmacher ................................. 38 Rede über das eigene Land – Von Marcel Reich-Ranicki ... 55 Marcel Reich-Ranicki – Stellungnahme zu Vorwürfen ..... 82 »Mein Leben«: Das Buch und der Film 85 Die Quellen seiner Leidenschaft – Von Frank Schirrmacher � 86 Es gibt keinen Tag, an dem ich nicht ans Getto denke – Das Gespräch führten Michael Hanfeld und Felicitas von Lovenberg ................................... 95 Stille Hoffnung, nackte Angst: Marcel-Reich-Ranicki und die Gruppe 47 107 Alles war von Hass und Gunst verwirrt – Von Hubert Spiegel 108 Und alle, ausnahmslos alle respektierten diesen Mann – Von Marcel-Reich-Ranicki ....................... 112 Das Ende der Gruppe 47 – Von Marcel Reich-Ranicki .... 116 Große Projekte: die Frankfurter Anthologie und der »Kanon« 125 Der Kanonist – Das Gespräch führte Hubert Spiegel .... -

Stunde Null: the End and the Beginning Fifty Years Ago." Their Contributions Are Presented in This Booklet

STUNDE NULL: The End and the Beginning Fifty Years Ago Occasional Paper No. 20 Edited by Geoffrey J. Giles GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE WASHINGTON, D.C. STUNDE NULL The End and the Beginning Fifty Years Ago Edited by Geoffrey J. Giles Occasional Paper No. 20 Series editors: Detlef Junker Petra Marquardt-Bigman Janine S. Micunek © 1997. All rights reserved. GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE 1607 New Hampshire Ave., NW Washington, DC 20009 Tel. (202) 387–3355 Contents Introduction 5 Geoffrey J. Giles 1945 and the Continuities of German History: 9 Reflections on Memory, Historiography, and Politics Konrad H. Jarausch Stunde Null in German Politics? 25 Confessional Culture, Realpolitik, and the Organization of Christian Democracy Maria D. Mitchell American Sociology and German 39 Re-education after World War II Uta Gerhardt German Literature, Year Zero: 59 Writers and Politics, 1945–1953 Stephen Brockmann Stunde Null der Frauen? 75 Renegotiating Women‘s Place in Postwar Germany Maria Höhn The New City: German Urban 89 Planning and the Zero Hour Jeffry M. Diefendorf Stunde Null at the Ground Level: 105 1945 as a Social and Political Ausgangspunkt in Three Cities in the U.S. Zone of Occupation Rebecca Boehling Introduction Half a century after the collapse of National Socialism, many historians are now taking stock of the difficult transition that faced Germans in 1945. The Friends of the German Historical Institute in Washington chose that momentous year as the focus of their 1995 annual symposium, assembling a number of scholars to discuss the topic "Stunde Null: The End and the Beginning Fifty Years Ago." Their contributions are presented in this booklet. -

Berg Literature Festival Committee) Alexandra Eberhard Project Coordinator/Point Person Prof

HEIDELBERG UNESCO CITY OF LITERATURE English HEIDEL BERG CITY OF LITERATURE “… and as Carola brought him to the car she surprised him with a passionate kiss before hugging him, then leaning on him and saying: ‘You know how really, really fond I am of you, and I know that you are a great guy, but you do have one little fault: you travel too often to Heidelberg.’” Heinrich Böll Du fährst zu oft nach Heidelberg in Werke. Kölner Ausgabe, vol. 20, 1977–1979, ed. Ralf Schell and Jochen Schubert et. al., Kiepenheuer & Witsch Verlag, Cologne, 2009 “One thinks Heidelberg by day—with its surroundings—is the last possibility of the beautiful; but when he sees Heidelberg by night, a fallen Milky Way, with that glittering railway constellation pinned to the border, he requires time to consider upon the verdict.” Mark Twain A Tramp Abroad Following the Equator, Other Travels, Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., New York, 2010 “The banks of the Neckar with its chiseled elevations became for us the brightest stretch of land there is, and for quite some time we couldn’t imagine anything else.” Zsuzsa Bánk Die hellen Tage S. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main, 2011 HEIDEL BERG CITY OF LITERATURE FIG. 01 (pp. 1, 3) Heidelberg City of Literature FIG. 02 Books from Heidelberg pp. 4–15 HEIDELBERG CITY OF LITERATURE A A HEIDELBERG CITY OF LITERATURE The City of Magical Thinking An essay by Jagoda Marinic´ 5 I think I came to Heidelberg in order to become a writer. I can only assume so, in retro spect, because when I arrived I hadn’t a clue that this was what I wanted to be. -

Images of the German Soldier (1985-2008)

Soldiering On: Images of the German Soldier (1985-2008) DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Kevin Alan Richards Graduate Program in Germanic Languages and Literatures The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: Professor John E. Davidson, Advisor Professor Anna Grotans Professor Katra Byram Copyright by Kevin Alan Richards 2012 Abstract The criminal legacy of National Socialism cast a shadow of perpetration and collaboration upon the post-war image of the German soldier. These negative associations impeded Helmut Kohl’s policy to normalize the state use of the military in the mid-eighties, which prompted a politically driven public relations campaign to revise the image of the German soldier. This influx of new narratives produced a dynamic interplay between political rhetoric and literature that informed and challenged the intuitive representations of the German soldier that anchor positions of German national identity in public culture. This study traces that interplay via the positioning of those representations in relation to prototypes of villains, victims, and heroes in varying rescue narrative accounts in three genre of written culture in Germany since 1985: that is, since the overt attempts to change the function of the Bundeswehr in the context of (West) German normalization began to succeed. These genre are (1) security publications (and their political and academic legitimizations), (2) popular fantasy literature, and (3) texts in the tradition of the Vergangenheitsbewältigung. I find that the accounts presented in the government’s White Papers and by Kohl, Nolte, and Hillgruber in the mid-1980s gathered momentum over the course of three decades and dislodged the dominant association of the German soldier with the villainy of National Socialism. -

Rewriting GDR History: the Christa Wolf Controversy

GDR Bulletin Volume 17 Issue 1 Spring Article 15 1991 Rewriting GDR History: The Christa Wolf Controversy Anna K. Kuhn University of California, Davis Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/gdr This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Kuhn, Anna K. (1991) "Rewriting GDR History: The Christa Wolf Controversy," GDR Bulletin: Vol. 17: Iss. 1. https://doi.org/10.4148/gdrb.v17i1.1088 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in GDR Bulletin by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact cads@k- state.edu. I have been highly critical of the performanceKuhn: Rewritingof GDR the GDR's History: The Christaso far Wolf contributed. Controversy fledgling democratic movernents.? The point, however, is that to For the very first time, I would argue paradoxical1y, there is now conflate, say, intellectual figures from Btindnis 90 with leading an unparal1eledopportunity for GDR scholars real1yto get down to members of the Writers' Union by bracketing them all as the work. Now that the archives may be opened, historians, intellectuals is to commit a serious error. This is not a backhanded sociologists, and literary critics have their work cut out for them- relapse into the old division between "good" and "bad" Germans provided the historical record can be saved from the rapacious which was promoted here after the Second World War (and grasp of cynical politicians, and the sad legacy of academic acquired something of a life of its own in the sub-genre of GDR apologetics can be worked through and transcended in the spirit of studies), but a plea for methodological clarity, for a more nuanced genuine understanding. -

Kersten, Jens. “A Farewell to Residual Risk? a Legal Perspective on the Risks of Nuclear Power After Fukushima,” RCC Perspectives 2012, No

How to cite: Kersten, Jens. “A Farewell to Residual Risk? A Legal Perspective on the Risks of Nuclear Power after Fukushima,” RCC Perspectives 2012, no. 1, 51–64. All issues of RCC Perspectives are available online. To view past issues, and to learn more about the Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society, please visit www.rachelcarsoncenter.de. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society Leopoldstrasse 11a, 80802 Munich, GERMANY ISSN 2190-8087 © Copyright is held by the contributing authors. Europe After Fukushima 51 Jens Kersten A Farewell to Residual Risk? A Legal Perspective on the Risks of Nuclear Power after Fukushima. Following the “slow-motion catastrophe“1 that unfolded at Fukushima in March 2011, the German political establishment reacted by accelerating its controversial phaseout from domestic nuclear energy production the following June. Proponents of nuclear power regard this to be a premature end of the non-military use of nuclear energy;2 as far as they are concerned, Germany’s nuclear safety record has not been compromised by the Japanese reactor disaster. On the contrary, they argue that a rash jettisoning of nuclear technologies will weaken energy safety in Germany. For many pro-nuclear advo- cates, it is ultimately hypocritical for Germany to halt the domestic production of nuclear power while continuing to import it from neighbouring countries. Critics of nuclear power, on the other hand, consider the accelerated exit strategy long overdue.3 Coming after Three Mile Island and Chernobyl, Fukushima was hardly just another isolated ac- cident; the Japanese reactor debacle—with its catastrophic human, social, ecological, and economic consequences—proved once again the latent dangers of nuclear power plants. -

Downloaded Texts, Or to Solve Problems with Others

15 Studien und Berichte der Arbeitsstelle Fernstudienforschung der Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg Band 15 Otto Peters is one of the most prominent writers on distance Otto Peters education theory. His work spans from the late sixties when he developed his theory of distance education as ‘most industrial form of education’ to this decade when he explored the ‘new learning spaces’ afforded by digital technology. Against the Tide In this book Peters changed his vantage point: He introduces 21 authors critical of digitalization who examine the collateral damage done by the digital technology on which the new forms Critics of Digitalisation of learning at a distance, of which Peters was one of the most prominent theoreticians, depend. According to the motto he Warners, Sceptics, Scaremongers, Apocalypticists choose for this volume that “nothing is true anymore without its 20 Portraits opposite” he wants distance education enthusiasts to brave the ambiguities and trade-offs. Only then the distance educator is able to recognize the profound impact and breadth of digitalization without being naïve about it. Critics of Digitalisation ide Against the T Otto Peters: BIS-Verlag der Carl von Ossietzky Universität ISBN 978-3-8142-2285-1 Oldenburg Umschlag-ASF-Bd15.indd 1 27.06.2013 09:26:42 Studien und Berichte der Arbeitsstelle Fernstudienforschung der Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg Volume 15 Otto Peters Against the Tide Critics of Digitalisation Warners, Sceptics, Scaremongers, Apocalypticists 20 Portraits BIS-Verlag der Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg Studien und Berichte der Arbeitsstelle Fernstudienforschung der Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg Herausgeber: Dr. Ulrich Bernath Prof. -

Introduction

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-86495-4 - German Intellectuals and the Nazi Past A. Dirk Moses Excerpt More information Introduction The proposition that the Federal Republic of Germany has developed a healthy democratic culture centered around memory of the Holocaust has almost become a platitude.1 Symbolizing the relationship between the Federal Repub- lic’s liberal political culture and honest reckoning with the past, an enormous Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe adjacent to the Bundestag (Federal Parliament) and Brandenburg Gate in the national capital was unveiled in 2005. States usually erect monuments to their fallen soldiers, after all, not to the vic- tims of these soldiers. In the eyes of many, the West German and, since 1990, the united German experience has become the model of how post-totalitarian and postgenocidal societies “come to terms with the past.”2 Germany now seemed no different from the rest of Europe – or, indeed, from the West generally. Jews from Eastern Europe are as happy to settle there as they are to emigrate to Israel, the United States, or Australia.3 1 Bill Niven, Facing the Nazi Past: United Germany and the Legacy of the Third Reich (London and New York, 2002). For an excellent overview of postwar memory politics, see Andrew H. Beattie, “The Past in the Politics of Divided and Unified Germany,” in Max Paul Friedman and Padraic Kenney, eds., Partisan Histories: The Past in Contemporary Global Politics (Houndmills, 2005), 17–38. 2 For example, Daniel J. Goldhagen, “Modell Bundesrepublik: National History, Democracy and Internationalization in Germany,” Common Knowledge, 3 (1997), 10–18. -

Wider Ein Skandalbuch - Der Streit Über Martin Walsers "Tod Eines Kritikers" Unter Literaturkritischem, Politischem Und Ökonomischem Aspekt

Wider ein Skandalbuch - Der Streit über Martin Walsers "Tod eines Kritikers" unter literaturkritischem, politischem und ökonomischem Aspekt- Kai Köhler (Seoul National Univ.) Schriftsteller brauchen die Buchkritik: Denn ihre Bücher sollen bekannt und verkauft werden, sie selbst berühmt und beachtet. - Schriftsteller hassen die Buchkritik: An einem einzigen Nachmittag vermag der Kritiker, das Schaffen eines ganzen Jahres zu zerschlagen. Viele Autoren haben wohl einmal insgeheim den "Tod eines Kritikers" gewünscht. Martin Walser, nach Günter Grass der bekannteste deutsche Autor der Gegenwart, hat ihnen den Roman geschrieben. Damit brachte er die Kritiker nicht zum Schweigen. Im Gegenteil: Während im Normalfall ein Buch erst nach Erscheinen gelobt oder getadelt wird, brach diesmal der Streit schon los, bevor das Manuskript gedruckt wurde. Problem war, daß Walser den Mord an einem Kritiker jüdischer Herkunft imaginierte; an einem Kritiker, der leicht als Marcel Reich-Ranicki dechiffrierbar war, der nur mit viel Mühe und Glück den faschistischen Völkermord überlebt hatte. Damit war ein Skandal da und nützte wiederum dem Autor: In kürzester Zeit wurden 200 000 Exemplare des Romans verkauft. Der Verdacht entstand, Walser habe gezielt einen Streit provoziert, um Aufmerksamkeit auf sein Buch zu lenken. Der Buchmarkt ist zwar ein Markt, aber vergleichsweise ruhig und behäbig; anspruchsvolle Literatur ist Angelegenheit einer Minderheit. 224 Kai Köhler Damit es in diesem Bereich überhaupt zu einem Skandal kommt, müssen also verschiedene Faktoren zusammentreffen. Im diesem Fall gab es persönliche, politische und wirtschaftliche Konflikte. Erst sie alle zusammen konnten die Auseinandersetzung verursachen, die es um Walsers Buch tatsächlich gab. Um den Roman selbst l soll es hier nicht gehen. Meine These, daß es sich um einen antisemitischen Roman handelt, habe ich bereits während der Debatte im Frühjahr 2002 formuliert. -

Martin Walser's Tod Eines Kritikers

Stuart Parkes Martin Walser’s Tod eines Kritikers: A ‘Crime’ of Anti-Semitism? Even before the publication of Tod eines Kritikers, Martin Walser found himself accused by the critic Frank Schirrmacher of having written an anti-Semitic attack on Marcel Reich-Ranicki. When the text became available, others followed suit and Walser’s whole oeuvre was examined for the same ‘crime’. Walser had many defenders and, on the basis of the opposing comments, it is impossible to reach a conclusion. An examination of the text is made difficult by the narrative structure. Although Schirrmacher’s accusation appears dubious, the satirical attack on Reich-Ranicki and critics in general in the television age does not constitute one of Walser’s best novels. It is normally axiomatic that awareness that a crime has been committed rests on the existence of evidence of that fact. If one takes the example of what is generally seen as the most heinous of crimes, namely murder, it is usually the discovery of a body that will provide such evidence. If this principle is applied to a ‘text crime’, then one might assume that the very least that could be expected would be the existence of a text. This was hardly the case, not even for his journalist colleagues, not to mention the general public, when the head of the Feuilleton section of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Frank Schirrmacher, accused Walser of such a crime in the 29 May 2002 edition of his paper. 1 Walser had personally handed over to the newspaper an uncorrected copy of his Tod eines Kritikers manuscript in the hope and probably the expectation that, in keeping with a tradition going back a quarter of a century, it would serialise the work prior to or simultaneously with its publication in book form. -

Fall 2000

WORLD WAR TWO STUDIES ASSOCIATION (formerly American Committee on the History ofthe Second World War) DOllald S. DCl\vikr. Clwimltm Mark P. Pnrillo. Secrelary 1/1111 D~pal1l11~1lt of lIislOry Ncws!£'ucr Edilor SOUl hem 1I1il\0is Ullivcrsily Dep;Ulment of History a! Clrbondalc 208 Eisenhower Hall Cubontl:1lc, Illinois 62901·4519 Knnsas Stale University tlc.'rll'ilcr~,.'",itl\l'''j'/, nct Mnnh:lllnll. KnllsDS e,65Ob-1 002 785-532-0374 Permanent Directors FJ\.'\ 785-532-7004 parillof.wKsu.ctlu Charles F. Delzell V<l.nderbill UniversilY James t.hnnnl1, Assoctmc £llilOr amI Wclmwstcr Allhur L. Funk DC'panmelll of HislOry G:linesville. Florida .:!08 Eisenhower H:l1I Kansns State University Terms £'.'Cpiring 1000 Mnnhilllall. Knns:lS 66506·1002 Cnd Boyd Robin Higham, Archivist Old Dominioll University Depanmenr of Hislory 208 Eis~nhower Hall Jalnl.·s L Cullins. Jr, NEWSLETTER Knnsns State Universily Middlebllrg, Virginia Manhalfan. Kansas 66506-1002 ISSN 0885-5668 John Lewis G~lddis The WWTSA is "JJilialetl willi: Ohio UnivtTsily Arnl:ric~ll1 J-1islOricnl Associ~lliOll Robin Higham 400 A Strct'l. S, E. Kansas State University Wn~hjllglol1, D.C, 20003 hfl/J: 1/llwlV"hcalltl,org Wan'en F Kimball No. 64 Fall 2000 Rutgers University, Nc:w<l.rk Comite lntem.uionnl d'Hislolrc de 1:1 DC:Ll~il:llll' Gucm: Mondiale AII;U1 R.Milletl Hemy ROUSSl). SccrcflIrv Gel/eml Ohio St:.l.h: University Instilu( d'Hislolrc du Temps Presenl (CcllIrc n:llional dt: In r¢eh~rchc A giles F. Peterson scielltifiqw.: lCNRSJ) J-1oo\'~r Institution Ecole Nonnale Superieure de Cachan b I, ;lVcnuc du President Wilson Russell F.