Germany's Literary Intellectuals and the End of the Cold

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reviews of Recent Publications

Studies in 20th Century Literature Volume 19 Issue 2 Article 10 6-1-1995 Reviews of recent publications Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the French and Francophone Literature Commons, German Language and Literature Commons, Modern Literature Commons, and the Spanish and Portuguese Language and Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation (1995) "Reviews of recent publications," Studies in 20th Century Literature: Vol. 19: Iss. 2, Article 10. https://doi.org/10.4148/2334-4415.1376 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reviews of recent publications Abstract Adelson, Leslie A. Making Bodies Making History: Feminism and German Identity by Sander L. Gilman Barrat, Barnaby B. Psychoanalysis and the Post-Modern Impulse: Knowing and Being Since Freud's Psychology by Mitchell Greenberg Calinescu, Matei. Rereading by Laurence M. Porter Donahue, Neil H. Forms of Disruption: Abstraction in Modern German Prose by Burton Pike Feminisms of the Belle Epoque, A Historical and Literary Anthology. Jennifer Waelti-Walters and Steven C. Hause, Eds. (Translated by Jette Kjaer, Lydia Willis, and Jennifer Waelti-Walters by Christiane J.P. Makward Hutchinson, Peter. Stefan Heym: The Perpetual Dissident by Susan M. Johnson Julien, Eileen. African Novels and the Question of Orality by Lifongo Vetinde Kristof, Agota. Le Troisième Mensonge by Jane Riles Laronde, Michel. -

Schnelle Hilfe Durch D2

11 N /A- B i N ^ *c B R L N E R M O R G E N N G DER TAGESSPIEGEL COGNOSCERE Aus -1 rv\ * Berlin und / 1 ~n rvn f " / Ndl. 2,45 hfl / Frankr. 7,80 KP / Ital. 2925 L / Schweiz 2,45 str / . rr~~ « BERLIN, MONTAG, 17. OKTOBER 1994 / 50. Jahrgang / Nr. 15 064 1 UM Brandenburg / 1,31) 1JJV1 wärts / Ösrerr. 14 öS / Span. 200 Pias / Großbr. 140 p / Luxembg. 25 fr / AbOZZA BERLIN SPORT KULTUR Nichts ist unmöglich Das Bundesarchiy Michael Schumacher hat das Fragen an die deutsche VON GERD APPENZELLER zieht in die einstigen Formel-1 -Rennen in Jerez Geschichte - eine Ausstellung ie Wähler haben gestern, wenn Andrews-Barracks seiteio gewonnen seiteis zieht um SEHE 21 auch hauchdünn, die bisherige DRegierungskoalition bestätigt. Das Bedürfnis nach Sicherheit und Kontinui- tät wog schwerer als der Wunsch nach Veränderung, wenn auch bei weitem nicht in dem Ausmaß, wie es sich dei Kanzler gewünscht hätte. Dennoch: Hel- Hauchdünne Mehrheit für Kohl und Kinkel mut Kohl kann vermutlich im Amt blei- ben. Den Willen dazu hat er gestern Vorsprung schmolz im Lauf des Abends bis auf zwei Sitze / Gysi, Heym, Luft und Müller gewinnen PDS-Direktmandate in Berlin / FDP bei abend unmißverständlich bekundet. Sei- ne Feststellung, er verfüge über eine re- über sechs Prozent / Geringe Wahlbeteiligung / SPD in Berlin stärkste Partei / Liberale bei Landtagswahlen gescheitert / SPD im Saarland vorn gierungsfähige Mehrheit ist richtig, wenn der liberale Partner bei der Stange Tsp. BONN/BERLIN. Die Koalition von Union und FDP kann in Bonn voraussicht- bleibt. Diesem blieb die Verbannung aus lich mit der hauchdünnen Mehrheit von zwei Sitzen weiterregieren. -

Dr. Otto Graf Lambsdorff F.D.P

Plenarprotokoll 13/52 Deutscher Bundestag Stenographischer Bericht 52. Sitzung Bonn, Donnerstag, den 7. September 1995 Inhalt: Zur Geschäftsordnung Dr. Uwe Jens SPD 4367 B Dr. Peter Struck SPD 4394B, 4399A Dr. Otto Graf Lambsdorff F.D.P. 4368B Joachim Hörster CDU/CSU 4395 B Kurt J. Rossmanith CDU/CSU . 4369 D Werner Schulz (Berlin) BÜNDNIS 90/DIE Dr. Norbert Blüm, Bundesminister BMA 4371 D GRÜNEN 4396 C Rudolf Dreßler SPD 4375 B Jörg van Essen F.D.P. 4397 C Eva Bulling-Schröter PDS 4397 D Dr. Gisela Babel F.D.P 4378 A Marieluise Beck (Bremen) BÜNDNIS 90/ Tagesordnungspunkt 1 (Fortsetzung): DIE GRÜNEN 4379 C a) Erste Beratung des von der Bundesre- Hans-Joachim Fuchtel CDU/CSU . 4380 C gierung eingebrachten Entwurfs eines Rudolf Dreßler SPD 4382A Gesetzes über die Feststellung des Annelie Buntenbach BÜNDNIS 90/DIE Bundeshaushaltsplans für das Haus- GRÜNEN 4384 A haltsjahr 1996 (Haushaltsgesetz 1996) (Drucksache 13/2000) Dr. Gisela Babel F.D.P 4386B Manfred Müller (Berlin) PDS 4388B b) Beratung der Unterrichtung durch die Bundesregierung Finanzplan des Bun- Ulrich Heinrich F D P. 4388 D des 1995 bis 1999 (Drucksache 13/2001) Ottmar Schreiner SPD 4390 A Dr. Günter Rexrodt, Bundesminister BMWi 4345 B Dr. Norbert Blüm CDU/CSU 4390 D - Ernst Schwanhold SPD . 4346D, 4360 B Gerda Hasselfeldt CDU/CSU 43928 Anke Fuchs (Köln) SPD 4349 A Dr. Jürgen Rüttgers, Bundesminister BMBF 4399B Dr. Hermann Otto Solms F.D.P. 4352A Doris Odendahl SPD 4401 D Birgit Homburger F D P. 4352 C Günter Rixe SPD 4401 D Ernst Hinsken CDU/CSU 4352B, 4370D, 4377 C Dr. -

Über Gegenwartsliteratur About Contemporary Literature

Leseprobe Über Gegenwartsliteratur Interpretationen und Interventionen Festschrift für Paul Michael Lützeler zum 65. Geburtstag von ehemaligen StudentInnen Herausgegeben von Mark W. Rectanus About Contemporary Literature Interpretations and Interventions A Festschrift for Paul Michael Lützeler on his 65th Birthday from former Students Edited by Mark W. Rectanus AISTHESIS VERLAG ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Bielefeld 2008 Abbildung auf dem Umschlag: Paul Klee: Roter Ballon, 1922, 179. Ölfarbe auf Grundierung auf Nesseltuch auf Karton, 31,7 x 31,1 cm. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. © VG BILD-KUNST, Bonn 2008 Bibliographische Information Der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliographie; detaillierte bibliographische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.ddb.de abrufbar. © Aisthesis Verlag Bielefeld 2008 Postfach 10 04 27, D-33504 Bielefeld Satz: Germano Wallmann, www.geisterwort.de Druck: docupoint GmbH, Magdeburg Alle Rechte vorbehalten ISBN 978-3-89528-679-7 www.aisthesis.de Inhaltsverzeichnis/Table of Contents Danksagung/Acknowledgments ............................................................ 11 Mark W. Rectanus Introduction: About Contemporary Literature ............................... 13 Leslie A. Adelson Experiment Mars: Contemporary German Literature, Imaginative Ethnoscapes, and the New Futurism .......................... 23 Gregory W. Baer Der Film zum Krug: A Filmic Adaptation of Kleist’s Der zerbrochne Krug in the GDR ......................................................... -

Revisiting Zero Hour 1945

REVISITING ZERO-HOUR 1945 THE EMERGENCE OF POSTWAR GERMAN CULTURE edited by STEPHEN BROCKMANN FRANK TROMMLER VOLUME 1 American Institute for Contemporary German Studies The Johns Hopkins University REVISITING ZERO-HOUR 1945 THE EMERGENCE OF POSTWAR GERMAN CULTURE edited by STEPHEN BROCKMANN FRANK TROMMLER HUMANITIES PROGRAM REPORT VOLUME 1 The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies. ©1996 by the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies ISBN 0-941441-15-1 This Humanities Program Volume is made possible by the Harry & Helen Gray Humanities Program. Additional copies are available for $5.00 to cover postage and handling from the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies, Suite 420, 1400 16th Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036-2217. Telephone 202/332-9312, Fax 202/265- 9531, E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.aicgs.org ii F O R E W O R D Since its inception, AICGS has incorporated the study of German literature and culture as a part of its mandate to help provide a comprehensive understanding of contemporary Germany. The nature of Germany’s past and present requires nothing less than an interdisciplinary approach to the analysis of German society and culture. Within its research and public affairs programs, the analysis of Germany’s intellectual and cultural traditions and debates has always been central to the Institute’s work. At the time the Berlin Wall was about to fall, the Institute was awarded a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to help create an endowment for its humanities programs. -

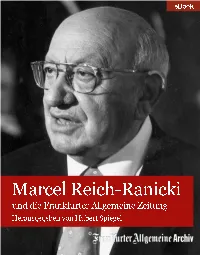

Marcel Reich-Ranicki

eBook Marcel Reich-Ranicki und die Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung Herausgegeben von Hubert Spiegel Marcel Reich-Ranicki und die Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung Herausgegeben von Hubert Spiegel F.A.Z.-eBook 21 Frankfurter Allgemeine Archiv Projektleitung: Franz-Josef Gasterich Produktionssteuerung: Christine Pfeiffer-Piechotta Redaktion und Gestaltung: Hans Peter Trötscher eBook-Produktion: rombach digitale manufaktur, Freiburg Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Rechteerwerb: [email protected] © 2013 F.A.Z. GmbH, Frankfurt am Main. Titelgestaltung: Hans Peter Trötscher. Foto: F.A.Z.-Foto / Barbara Klemm ISBN: 978-3-89843-232-0 Inhalt Ein sehr großer Mann 7 Marcel Reich-Ranicki ist tot – Von Frank Schirrmacher ..... 8 Ein Leben – Von Claudius Seidl .................... 16 Trauerfeier für Reich-Ranicki – Von Hubert Spiegel ...... 20 Persönlichkeitsbildung 25 Ein Tag in meinem Leben – Von Marcel Reich-Ranicki .... 26 Wie ein kleiner Setzer in Polen über Adolf Hitler trium- phierte – Das Gespräch führten Stefan Aust und Frank Schirrmacher ................................. 38 Rede über das eigene Land – Von Marcel Reich-Ranicki ... 55 Marcel Reich-Ranicki – Stellungnahme zu Vorwürfen ..... 82 »Mein Leben«: Das Buch und der Film 85 Die Quellen seiner Leidenschaft – Von Frank Schirrmacher � 86 Es gibt keinen Tag, an dem ich nicht ans Getto denke – Das Gespräch führten Michael Hanfeld und Felicitas von Lovenberg ................................... 95 Stille Hoffnung, nackte Angst: Marcel-Reich-Ranicki und die Gruppe 47 107 Alles war von Hass und Gunst verwirrt – Von Hubert Spiegel 108 Und alle, ausnahmslos alle respektierten diesen Mann – Von Marcel-Reich-Ranicki ....................... 112 Das Ende der Gruppe 47 – Von Marcel Reich-Ranicki .... 116 Große Projekte: die Frankfurter Anthologie und der »Kanon« 125 Der Kanonist – Das Gespräch führte Hubert Spiegel .... -

Alexander Kluge Raw Materials for the Imagination

FILM CULTURE IN TRANSITION Alexander Kluge Raw Materials for the Imagination EDITED BY TARA FORREST Amsterdam University Press Alexander Kluge Alexander Kluge Raw Materials for the Imagination Edited by Tara Forrest Front cover illustration: Alexander Kluge. Photo: Regina Schmeken Back cover illustration: Artists under the Big Top: Perplexed () Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam isbn (paperback) isbn (hardcover) e-isbn nur © T. Forrest / Amsterdam University Press, All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Every effort has been made to obtain permission to use all copyrighted illustra- tions reproduced in this book. Nonetheless, whosoever believes to have rights to this material is advised to contact the publisher. For Alexander Kluge …and in memory of Miriam Hansen Table of Contents Introduction Editor’s Introduction Tara Forrest The Stubborn Persistence of Alexander Kluge Thomas Elsaesser Film, Politics and the Public Sphere On Film and the Public Sphere Alexander Kluge Cooperative Auteur Cinema and Oppositional Public Sphere: Alexander Kluge’s Contribution to G I A Miriam Hansen ‘What is Different is Good’: Women and Femininity in the Films of Alexander Kluge Heide -

GESAMTARBEIT Kulturtechniken Des Kollektiven Bei Alexander Kluge

Jens Grimstein GESAMTARBEIT Kulturtechniken des Kollektiven bei Alexander Kluge Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Philosophie am Fachbereich Philosophie und Geisteswissenschaften der Freien Universität Berlin Gutachterinnen und Gutachter: Erstgutachterin: Frau Prof. Dr. Irene Albers Zweitgutachter: Herr PD Dr. Wolfram Ette Tag der Disputation: 03. Juli 2019 INHALTSVERZEICHNIS 1. Einleitung ............................................................................ 2 2. Begriffe (Theorie) ............................................................. 12 2.1. Kollektive................................................................................ 12 2.2. Kulturtechniken ...................................................................... 25 2.3. Arbeit ...................................................................................... 40 2.4. Gesamtarbeit ........................................................................... 47 3. Kluges Theoriearbeit (Theoros) ........................................ 57 3.1. Kluge und die Theorie ............................................................ 58 3.2. Kluge und die Kollektive ........................................................ 64 3.3. Kluge und die Kulturtechniken ............................................... 66 3.4. Die Kritische Theorie zwischen Aufklärung und Theorie der Kulturtechnik ............................................... 85 4. Medien (Textilia) .............................................................. 92 4.1. Zivilisation, Turm, Stadt -

Hostage to Feminism? the Success of Christa Wolf's Kassandra in Its 1984

This is a repository copy of Hostage to feminism? The success of Christa Wolf’s Kassandra in its 1984 English translation. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/127025/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Summers, C (2018) Hostage to feminism? The success of Christa Wolf’s Kassandra in its 1984 English translation. Gender and History, 30 (1). pp. 226-239. ISSN 0953-5233 https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0424.12345 © 2018 John Wiley & Sons Ltd. This is the peer reviewed version of the following article: Summers, C (2018) Hostage to feminism? The success of Christa Wolf’s Kassandra in its 1984 English translation. Gender and History, 30 (1). pp. 226-239, which has been published in final form at https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0424.12345. This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance with Wiley Terms and Conditions for Self-Archiving. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. -

The Rhetorical Crisis of the Fall of the Berlin Wall

THE RHETORICAL CRISIS OF THE FALL OF THE BERLIN WALL: FORGOTTEN NARRATIVES AND POLITICAL DIRECTIONS A Dissertation by MARCO EHRL Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Nathan Crick Committee Members, Alan Kluver William T. Coombs Gabriela Thornton Head of Department, J. Kevin Barge August 2018 Major Subject: Communication Copyright 2018 Marco Ehrl ABSTRACT The accidental opening of the Berlin Wall on November 9th, 1989, dismantled the political narratives of the East and the West and opened up a rhetorical arena for political narrators like the East German citizen movements, the West German press, and the West German leadership to define and exploit the political crisis and put forward favorable resolutions. With this dissertation, I trace the neglected and forgotten political directions as they reside in the narratives of the East German citizen movements, the West German press, and the West German political leadership between November 1989 and February 1990. The events surrounding November 9th, 1989, present a unique opportunity for this endeavor in that the common flows of political communication between organized East German publics, the West German press, and West German political leaders changed for a moment and with it the distribution of political legitimacy. To account for these new flows of political communication and the battle between different political crisis narrators over the rhetorical rights to reestablish political legitimacy, I develop a rhetorical model for political crisis narrative. This theoretical model integrates insights from political crisis communication theories, strategic narratives, and rhetoric. -

36429721.Pdf

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Publikationsserver der RWTH Aachen University Reflexionen über Entfremdungserscheinungen in Christa Wolfs Medea. Stimmen Yildiz Aydin Reflexionen über Entfremdungserscheinungen in Christa Wolfs Medea. Stimmen Von der Philosophischen Fakultät der Rheinisch-Westfälischen Technischen Hochschule Aachen zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades einer Doktorin der Philosophie genehmigte Dissertation von Yildiz Aydin, M.A. Berichter: Universitätsprofessor Dr. Dieter Breuer Universitätsprofessorin Dr. Monika Fick Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 13.09.2010 Diese Dissertation ist auf den Internetseiten der Hochschulbibliothek online verfügbar. Meiner Mutter Danksagung Für meine Doktorarbeit schulde ich sehr vielen Menschen einen herzlichen Dank. An erster Stelle möchte ich meinem Doktorvater, Herrn Prof. Dr. Dieter Breuer, danken. Ohne seine weitreichende Unterstützung, seinen Ansporn und seine konstruktive Kritik wäre diese Dissertation nie entstanden. Viele haben diese Arbeit mit motivierendem Zuspruch unterstützt. Ihnen allen gehört mein persönlicher Dank, insbesondere an Josipa Spoljaric für die jahrelange freundschaftliche Unter- stützung und für endlose literarische Gespräche. Frau Sabine Durchholz war mir bei der End- korrektur und Layoutgestaltung sehr behilflich, wofür ich ihr danke. Zum Schluss möchte ich mich ganz herzlich bei meiner Mutter, Sevim Aydin, und meinen Geschwistern, Hülya, Derya, Ayla und Murat bedanken, die mir sehr viel Geduld entgegen- -

Stunde Null: the End and the Beginning Fifty Years Ago." Their Contributions Are Presented in This Booklet

STUNDE NULL: The End and the Beginning Fifty Years Ago Occasional Paper No. 20 Edited by Geoffrey J. Giles GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE WASHINGTON, D.C. STUNDE NULL The End and the Beginning Fifty Years Ago Edited by Geoffrey J. Giles Occasional Paper No. 20 Series editors: Detlef Junker Petra Marquardt-Bigman Janine S. Micunek © 1997. All rights reserved. GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE 1607 New Hampshire Ave., NW Washington, DC 20009 Tel. (202) 387–3355 Contents Introduction 5 Geoffrey J. Giles 1945 and the Continuities of German History: 9 Reflections on Memory, Historiography, and Politics Konrad H. Jarausch Stunde Null in German Politics? 25 Confessional Culture, Realpolitik, and the Organization of Christian Democracy Maria D. Mitchell American Sociology and German 39 Re-education after World War II Uta Gerhardt German Literature, Year Zero: 59 Writers and Politics, 1945–1953 Stephen Brockmann Stunde Null der Frauen? 75 Renegotiating Women‘s Place in Postwar Germany Maria Höhn The New City: German Urban 89 Planning and the Zero Hour Jeffry M. Diefendorf Stunde Null at the Ground Level: 105 1945 as a Social and Political Ausgangspunkt in Three Cities in the U.S. Zone of Occupation Rebecca Boehling Introduction Half a century after the collapse of National Socialism, many historians are now taking stock of the difficult transition that faced Germans in 1945. The Friends of the German Historical Institute in Washington chose that momentous year as the focus of their 1995 annual symposium, assembling a number of scholars to discuss the topic "Stunde Null: The End and the Beginning Fifty Years Ago." Their contributions are presented in this booklet.