7 X 11 Long.P65

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TRISTAN UND MATHILDE Inspiration – Werk – Rezeption

TRISTAN UND MATHILDE Inspiration – Werk – Rezeption Sonderausstellung 29. 11. 2014 bis 11. 01. 2015 Stadtschloss Eisenach 2 / 3 Nicolaus J. Oesterlein (1841–1898), Sammler und Initiator der Sammlung DIE EISENACHER RICHARD-WAGNER-SAMMLUNG In der Reuter-Villa am Fuße der Wartburg schlummern manch vergessene Schätze: Das Abbild einer römischen Villa beherbergt die zweitgrößte Richard-Wagner-Sammlung der Welt. Den Grundstein hierfür legte der glühende Wagner-Verehrer Nicolaus J. Oesterlein (1841–1898) mit einer akribisch angelegten Sammlung von ca. 25.000 Objekten – darunter etwa 200 Handschriften und Originalbriefe Wagners, 700 Theaterzettel, 1000 Graphiken und Fotos, 15.000 Zeitungsausschnitte, handgeschriebene Partituren. Das Herzstück der Sammlung ist eine über 5.500 Bücher umfassende Bibliothek, die neben sämtlichen Wer- ken des Komponisten den fast lückenlosen Bestand der Wagner-Sekundärliteratur des 19. Jahrhunderts enthält. Das Archivmaterial stellt nicht nur einen umfassenden Zugang zu Wagners kompositori- schem und literarischem Schaffen dar, sondern ebenso zu musikästhetischen, philoso- phischen, kulturgeschichtlichen und soziopolitischen Kontroversen des späten 19. Jahr- hunderts. Oesterleins Sammlung kann somit als ein Spiegelbild der Wagner-Rezeption gedeutet werden. Die Sonderausstellung »Tristan und Mathilde. Inspiration – Werk – Rezeption« rückt einige der exquisiten Exemplare aus der Sammlung erstmals wieder in die Öffentlichkeit, die auf diese Weise mit diesem unschätzbaren Kulturgut konfrontiert werden soll. Wie die Sammlung nach Eisenach kam In den 1870er Jahren begann Nicolaus J. Oesterlein mit einem enormen finanziellen Auf- wand und einer fast manischen Akribie alles zu sammeln, was mit dem Komponisten in Verbindung stand. 1887 eröffnete Oesterlein ein Privatmuseum in Wien – in den 1890er Jahren brachte er seinen vierbändigen Katalog heraus. Zu diesem Zeitpunkt umfasste seine Sammlung – nach eigenen Angaben – ca. -

My Musical Lineage Since the 1600S

Paris Smaragdis My musical lineage Richard Boulanger since the 1600s Barry Vercoe Names in bold are people you should recognize from music history class if you were not asleep. Malcolm Peyton Hugo Norden Joji Yuasa Alan Black Bernard Rands Jack Jarrett Roger Reynolds Irving Fine Edward Cone Edward Steuerman Wolfgang Fortner Felix Winternitz Sebastian Matthews Howard Thatcher Hugo Kontschak Michael Czajkowski Pierre Boulez Luciano Berio Bruno Maderna Boris Blacher Erich Peter Tibor Kozma Bernhard Heiden Aaron Copland Walter Piston Ross Lee Finney Jr Leo Sowerby Bernard Wagenaar René Leibowitz Vincent Persichetti Andrée Vaurabourg Olivier Messiaen Giulio Cesare Paribeni Giorgio Federico Ghedini Luigi Dallapiccola Hermann Scherchen Alessandro Bustini Antonio Guarnieri Gian Francesco Malipiero Friedrich Ernst Koch Paul Hindemith Sergei Koussevitzky Circa 20th century Leopold Wolfsohn Rubin Goldmark Archibald Davinson Clifford Heilman Edward Ballantine George Enescu Harris Shaw Edward Burlingame Hill Roger Sessions Nadia Boulanger Johan Wagenaar Maurice Ravel Anton Webern Paul Dukas Alban Berg Fritz Reiner Darius Milhaud Olga Samaroff Marcel Dupré Ernesto Consolo Vito Frazzi Marco Enrico Bossi Antonio Smareglia Arnold Mendelssohn Bernhard Sekles Maurice Emmanuel Antonín Dvořák Arthur Nikisch Robert Fuchs Sigismond Bachrich Jules Massenet Margaret Ruthven Lang Frederick Field Bullard George Elbridge Whiting Horatio Parker Ernest Bloch Raissa Myshetskaya Paul Vidal Gabriel Fauré André Gédalge Arnold Schoenberg Théodore Dubois Béla Bartók Vincent -

Espressivo Program Notes April 2018 the Evolution of Chamber Music For

Espressivo Program Notes April 2018 The evolution of chamber music for a mixed ensemble of winds and strings coincides with the domestication of the double bass. Previously used as an orchestral instrument or in dance music, the instrument was admitted into the salon in the late eighteenth century. The granddaddy of the genre is Beethoven’s Septet of 1800, for four strings, clarinet, horn and bassoon. Beethoven seems to have discovered that the largest string instrument, essentially doubling the cello an octave lower and with the capability to play six notes below the lowest note on the bassoon, provided overtones that enhanced the vibrations of the higher instruments. In any case, the popularity of the Septet, which sustains to this day, caused the original players to have a similar work commissioned from Franz Schubert, who added a second violin for his Octet (1824). (Espressivo performed it last season.) It is possible, if not probable, that Schubert’s good friend Franz Lachner wrote his Nonet for the same group, adding a flute, but the origins, and even the date of the composition are in dispute. An indicator might be the highlighting of the virtuosic violin part, as it would have been played by Ignaz Schuppanzigh, who had premiered both the Septet and the Octet. All three works, Septet, Octet and Nonet, have slow introductions to the first and last uptempo movements, and all include a minuet. All seem intended to please rather than to challenge. Beethoven’s Septet was commissioned by a noble patron for the delectation of his guests, as was Schubert’s Octet. -

From Page to Stage: Wagner As Regisseur

Wagner Ia 5/27/09 3:55 PM Page 3 Copyrighted Material From Page to Stage: Wagner as Regisseur KATHERINE SYER Nowadays we tend to think of Richard Wagner as an opera composer whose ambitions and versatility extended beyond those of most musicians. From the beginning of his career he assumed the role of his own librettist, and he gradually expanded his sphere of involvement to include virtually all aspects of bringing an opera to the stage. If we focus our attention on the detailed dramatic scenarios he created as the bases for his stage works, we might well consider Wagner as a librettist whose ambitions extended rather unusually to the area of composition. In this light, Wagner could be considered alongside other theater poets who paid close attention to pro- duction matters, and often musical issues as well.1 The work of one such figure, Eugène Scribe, formed the foundation of grand opera as it flour- ished in Paris in the second quarter of the nineteenth century. Wagner arrived in this operatic epicenter in the fall of 1839 with work on his grand opera Rienzi already under way, but his prospects at the Opéra soon waned. The following spring, Wagner sent Scribe a dramatic scenario for a shorter work hoping that the efforts of this famous librettist would help pave his way to success. Scribe did not oblige. Wagner eventually sold the scenario to the Opéra, but not before transforming it into a markedly imaginative libretto for his own use.2 Wagner’s experience of operatic stage produc- tion in Paris is reflected in many aspects of the libretto of Der fliegende Holländer, the beginning of an artistic vision that would draw him increas- ingly deeper into the world of stage direction and production. -

Tristan Und Isolde - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

איזולדה Isolde – garland of flowers in her blonde hair, which has thin plaits falling down her face from her forehead. Identify your Ascended Master إيزولدى http://www.egyptianoasis.net/showthread.php?t=8350 ِاي ُزول ِدِ Ιζόλδη ISOLDE …. The origins of this name are uncertain, though some Celtic roots have been suggested. It is possible that the name is ultimately Germanic, perhaps from a hypothetic name like Ishild, composed of the elements is "ice" and hild "battle". http://www.behindthename.com/name/isolde Tristan und Isolde - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tristan_und_Isolde Tristan und Isolde From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Tristan und Isolde ( Tristan and Isolde , or Tristan and Isolda , or Tristran and Ysolt ) is an opera, or music drama, in three acts by Richard Wagner to a German libretto by the composer, based largely on the romance by Gottfried von Strassburg. It was composed between 1857 and 1859 and premiered at the Königliches Hof- und Nationaltheater in Munich on 10 June 1865 with Hans von Bülow conducting. Wagner referred to the work not as an opera, but called it "eine Handlung" (literally a drama , a plot or an action ), which was the equivalent of the term used by the Spanish playwright Calderón for his dramas. Wagner's composition of Tristan und Isolde was inspired by the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer (particularly The World as Will and Representation ) and Wagner's affair with Mathilde Wesendonck. Widely acknowledged as one of the peaks of the operatic repertoire, Tristan was notable for Wagner's unprecedented use of chromaticism, tonality, orchestral colour and harmonic suspension. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 28,1908-1909, Trip

MECHANICS HALL . WORCESTER Twenty-eighth Season, I908-J909 Ionian ^ptpfjmuj GDrdf^fra MAX FIEDLER, Conductor ffrogramm? of a?* Third and Last Concert WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIP- TIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE TUESDAY EVENING, APRIL 20 AT 8. J 5 PRECISELY COPYRIGHT, 1908, BY C. A. ELLIS MANAGER PUBLISHED BY C. A. ELLIS, Mme. CECILE CHAMINADE The World's Greatest Woman Composer Mme. TERESA CARRENO The World's Greatest Woman Pianist Mme. LILLIAN NORDICA The World's Greatest Woman Singer USE ^^ Piano. THE JOHN CHURCH CO., 37 West 3*d Street New York City REPRESENTED BY THE JOHN CHURCH CO., 37 West 32d Street, New York City Boston Symphony Orchestra PERSONNEL TWENTY-EIOHTH SEASON, 1908-1909 MAX 1FIEDLER, Conductor First Violins. Hess, Willy Roth, O. Hoffmann, J, Krafft, W. Concert-master. Kuntz, D. Fiedler, E. Theodorowicz, J. Noach, S. Mahn, F. Eichheim, H, Bak, A. Mullaly, J. Strube, G. Rissland, K. Ribarsch, A. Traupe, W. Second Violins. Barleben, K. Akeroyd, J. Fiedler, B. Berger, H. Fiumara, P. Currier, F. Marble, E. Eichler, J. Tischer-Zeitz, H. Kuntz, A, Goldstein, H. Goldstein, S. Kurth, R. Werner, H. Violas. Fenr, E. Heindl, H. Zahn, F. Kolster, A. Krauss, H. Scheurer, K. Hoyer, H. Kluge, M. Sauer, G. Gietzen, A. Violoncellos. Warnke, H. Nagel, R. Barth, C. Loeffler, K Warnke, J. Keller, J. Kautzenbach, A. Nast, L. Hadley, A. Smalley, R. Basses. Keller, K. Agnesy, K. Seydel, T. Ludwig, O. Gerhardt, G. Kunze, M. Huber, E. Schurig, R. Flutes. Oboes. Clarinets. Bassoons. Maquarre, A. Longy, G. Grisez, G. Sadony, P. Brooke, A. Lenom, C. -

Das Rheingold by Richard Wagner CD 1 CD 1

WAGNER, R.: Ring des Nibelungen (Der) [Operas] 8.501403 https://www.naxos.com/catalogue/item.asp?item_code=8.501403 Das Rheingold by Richard Wagner Premiere: 22 September 1869 Das Rheingold (The Rhinegold) is the first of the four operas that constitute Richard Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen (The Ring of the Nibelung). It was originally written as an introduction to the tripartite Ring, but the cycle is now generally regarded as consisting of four individual operas. Das Rheingold received its premiere at the National Theatre in Munich on 22 September 1869, with August Kindermann in the role of Wotan, Heinrich Vogl as Loge, and Karl Fischer as Alberich. Wagner wanted this opera to be premiered as part of the entire cycle, but was forced to allow the performance at the insistence of his patron King Ludwig II of Bavaria. The opera received its premiere as part of the complete cycle on 13 August 1876, in the Bayreuther Festspielhaus. Das Rheingold von Richard Wagner Das Rheingold by Richard Wagner (English libretto) Personen Characters Wotan (Göttervater), Hoher Baß Wotan (ruler of the gods), Baritone Fricka (Göttin der Ehe), Tiefer Sopran Fricka (goddess of marriage). Mezzo-soprano Loge (Halb-Gott des Feuers), Tenor Loge (half-god of fire), Tenor Donner (ein Gott), Hoher Baß Donner (god of thunder), Baritone Froh (ein Gott), Tenor Froh (the fair god), Tenor Freia (Göttin der Jugend), Hoher Sopran Freia (goddess of youth and beauty), Soprano Erda (Urmutter Erde), Tiefer Sopran Erda (earth mother, goddess of wisdom), Mezzo-soprano Alberich (Nibelung), Hoher Baß Alberich (king of the Nibelungs). -

Angelo Neumann Y La Extraordinaria Aventura Del Teatro Itinerante Richard Wagner

TEXTO DE NICOLAS CRAPANNE ANGELO NEUMANN y la extraordinaria aventura del TEATRO ITINERANTE RICHARD WAGNER (el Richard-Wagner-Wander-Theater) Associació Wagneriana. Apartat postal 1159. Barcelona 08080 Http://www.associaciowagneriana.com [email protected] INDICE: PRELUDIO 3 I- SINSABORES FINANCIEROS EN BAYREUTH, CONSECUENCIAS DEL PRIMER FESTIVAL DE 1876 4 I-1. BAYREUTH, 30 DE AGOSTO 1876: TRIUNFO ABSOLUTO DE UN ESPECTÁCULO FUERA DE SERIE, LA OBRA DE TODA UNA VIDA I-2. BAYREUTH, 9 DE SEPTIEMBRE DE 1876: CRÓNICA DE UNA CATÁSTROFE ANUNCIADA II-ANGELO NEUMANN, ALGÚN ELEMENTO BIOGRÁFICO 6 II-1. UNA ELECCIÓN DE CARRERA ARTÍSTICA CONTRA LA AUTORIDAD FAMILIAR. II-2. BARÍTONO EN LA ÓPERA DE VIENA Y PRIMEROS ENCUENTROS CON RICHARD WAGNER II-3. DIRECTOR DE LA ÓPERA DE LEIPZIG III- EL RING DE LEIPZIG (1878), LA PRIMERA TETRALOGÍA "FUERA DE LOS MUROS" 10 III-1. PRIMER ENCUENTRO (ABORTADO] DE UN MAESTRO CON SU DISCÍPULO III-2. "TEMPESTAD EN LA CABEZA... DE RICHARD WAGNER". INICIO DE LAS PRIMERAS NEGOCIACIONES III-3. PREPARATIVOS CON VISTAS A LAS REPRESENTACIONES EN LEIPZIG. EL PRIMER RING DE LEIPZIG EN 1878 IV-BERLÍN, LUEGO LONDRES: EL RICHARD-WAGNER-THEATER VE LA LUZ 16 IV-1. LAS REPRESENTACIONES BERLINESAS: UN PERFUME DE PRUEBA AL PROYECTO DE NEUMANN (mayo de 1881) IV-2. RECONCILIARON, DISCUSIONES, NEGOCIACIONES Y CONTRATOS: EL RICHARD- WAGNER-WANDER-THEATER VE LA LUZ IV-3. LAS REPRESENTACIONES LONDINENSES V-EL RICHARD-WAGNER-THEATER DE ANGELO NEUMANN 23 V-1. VIAJAR TRASPASANDO FRONTERAS PARA HACER CONOCER MEJOR EL ARTE DE RICHARD WAGNER V-2. PRIMERA GIRA DEL RICHARD-WAGNER-WANDER-THEATER - (1 de septiembre de 1882 - 5 de junio de 1883) VI-ANGELO NEUMANN EN PRAGA Y EL ÚLTIMO VIAJE DEL RICHARD-WAGNER-THEATER EN RUSIA 28 VI-1. -

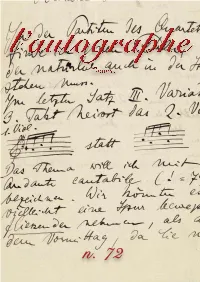

Genève L'autographe

l’autographe Genève l'autographe L’Autographe S.A. 24 rue du Cendrier, CH - 1201, Genève +41 22 510 50 59 (mobile) +41 22 523 58 88 (bureau) web: www.lautographe.com mail: [email protected] All autographs are offered subject to prior sale. Prices are quoted in US DOLLARS, SWISS FRANCS and EUROS and do not include postage. All overseas shipment will be sent by air. Orders above € 1000 benefits of free shipping. We accept payments via bank transfer, PayPal, and all major credit cards. We do not accept bank checks. Postfinance CCP 61-374302-1 3 rue du Vieux-Collège CH-1204, Genève IBAN: EUR: CH94 0900 0000 9175 1379 1 CHF: CH94 0900 0000 6137 4302 1 SWIFT/BIC: POFICHBEXXX paypal.me/lautographe The costs of shipping and insurance are additional. Domestic orders are customarily shipped via La Poste. Foreign orders are shipped with La Poste and Federal Express on request. 1. Richard Adler (New York City, 1921 - Southampton, 2012) Autograph dedication signed on the frontispiece of the musical score of the popular song “Whatever Lola Wants” from the musical comedy “Damn Yankees” by the American composer and producer of several Broadway shows and his partner Jerry Ross. 5 pp. In fine condition. Countersigned with signature and dated “6/2/55” by the accordionist Muriel Borelli. $ 125/Fr. 115/€ 110 2. Franz Allers (Carlsbad, 1905 - Paradise, 1995) Photo portrait with autograph dedication and musical quotation signed, dated June 1961 of the Czech born American conductor of ballet, opera and Broadway musicals. (8 x 10 inch.). In fine condition. -

Wagner 'S Das Liebesverbot

A l WAGNER 'S DAS LIEBESVERBOT THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By Danna Behne, B. M. E. Denton, Texas May, 1973 Behne, Danna, Wagner's Das Liebesverbot. Master of Music (Musicology), May, 1973, 192 pp., 162 illustrations, bibliography, 76 titles. Wagner's second opera Das Liebesverbot, composed in 1835 and first performed in Magdeburg in 1836, could be termed Wagner's "Italian" opera. It represents Wagner's attitudes and feelings at the time of its composition. During this period in Wagner's life the composer had be come particularly enchanted with Italian music and also with the Italian way of sensuous and carefree living. At the same time his disillusionment with German conservatism and pedantry also had an influence on the composition of this opera. Although Das Liebesverbot sounds for the most part like the French and Italian operas after which it was patterned, a few traits of the later Wagner can also be detected. The use of the leitmotif in Das Liebesverbot foreshadows its more highly developed use in the later dramas. The dramatic compactness in this early opera is also a characteristic trait of all of Wagner's operas. Das Liebesverbot was termed a "sin of my youth" by the composer and ordered never to be performed at Bayreuth. This decree was recently broken with the performance of the 1 2 opera by the Bayreuth International Youth Festival. Over the years a few other German and English theaters have staged Das Liebesverbot, among those being Munich, Leipzig, Berlin, Dortmund, Nottingham, and London. -

Richard Strauss

RICHARD STRAUSS: The Origin, Dissemination and Reception of his Mozart Renaissance Raymond lIolden I I \,--,~/ PhD Goldsmiths' College University of London 1 Abstract Richard Strauss holds an important place in the history of performance. Of the major musical figures active during the second half of the nineteenth and the first half of the twentieth centuries, his endeavours as a Mozartian are of particular importance. Strauss' special interest in the works of Mozart was seminal to both his performance and compositional aesthetics. As a result of this affinity, Strauss consciously set out to initiate a Mozart renaissance that embodied a precise set of principles and reforms. It was these principles and reforms, described as literalist, rather than those of artists such .as Gustav Mahler, who edited Mozart's works both musically and dramatically, that found further expression in the readings of, amongst others, Otto Klemperer, George Szell, Sir John Pritchard and Wolfgang Sawallisch. It is the aim of this dissertation to investigate Strauss' activities as a Mozartian and to assess his influence on subsequent generations of Mozart conductors. Accordingly, the dissertation is divided into an Introduction, five chapters, a Conclusion and thirteen appendices. These consider both the nature and ramifications of Strauss' reforms and performance aesthetic. Within this framework, the breadth of his renaissance; his choice of edition, cuts and revisions; his use of tempo, as a means of structural delineation; his activities with respect to the -

Copyright by Brian James Watson 2005

Copyright by Brian James Watson 2005 The Treatise Committee for Brian James Watson certifies that this is the approved version of the following treatise: Wagner’s Heldentenors: Uncovering the Myths Committee: K. M. Knittel, Supervisor William Lewis, Co-Supervisor Rose A. Taylor Michael C. Tusa John Weinstock Darlene Wiley Wagner’s Heldentenors: Uncovering the Myths by Brian James Watson, B.A., M.M. Treatise Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts The University of Texas at Austin August 2005 Acknowledgements This treatise would not have been possible without the assistance and encouragement of several people whom I would like to thank. First and foremost, I would like to thank Dr. K. M. Knittel for her careful supervision. Her advice and guidance helped shape this project and I am very grateful for her participation. I would also like to thank my co-supervisor, William Lewis, whose encouragement has been instrumental to my academic career. His singing helped stir my interest in Heldentenors. I am also grateful for the support of Darlene Wiley. Without her, my knowledge of vocal pedagogy would be quite limited. Rose Taylor should also be thanked for her positive attitude and encouragement. The other members of my committee should also be recognized. I want to thank Dr. Michael C. Tusa, for his participation on this committee and for his assistance in finding sources, and Dr. John Weinstock, for being a part of this committee. I would be remiss if I did not also thank my family, primarily my father for his understanding and sympathy.