Alan Krueck: Identity Crisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

My Musical Lineage Since the 1600S

Paris Smaragdis My musical lineage Richard Boulanger since the 1600s Barry Vercoe Names in bold are people you should recognize from music history class if you were not asleep. Malcolm Peyton Hugo Norden Joji Yuasa Alan Black Bernard Rands Jack Jarrett Roger Reynolds Irving Fine Edward Cone Edward Steuerman Wolfgang Fortner Felix Winternitz Sebastian Matthews Howard Thatcher Hugo Kontschak Michael Czajkowski Pierre Boulez Luciano Berio Bruno Maderna Boris Blacher Erich Peter Tibor Kozma Bernhard Heiden Aaron Copland Walter Piston Ross Lee Finney Jr Leo Sowerby Bernard Wagenaar René Leibowitz Vincent Persichetti Andrée Vaurabourg Olivier Messiaen Giulio Cesare Paribeni Giorgio Federico Ghedini Luigi Dallapiccola Hermann Scherchen Alessandro Bustini Antonio Guarnieri Gian Francesco Malipiero Friedrich Ernst Koch Paul Hindemith Sergei Koussevitzky Circa 20th century Leopold Wolfsohn Rubin Goldmark Archibald Davinson Clifford Heilman Edward Ballantine George Enescu Harris Shaw Edward Burlingame Hill Roger Sessions Nadia Boulanger Johan Wagenaar Maurice Ravel Anton Webern Paul Dukas Alban Berg Fritz Reiner Darius Milhaud Olga Samaroff Marcel Dupré Ernesto Consolo Vito Frazzi Marco Enrico Bossi Antonio Smareglia Arnold Mendelssohn Bernhard Sekles Maurice Emmanuel Antonín Dvořák Arthur Nikisch Robert Fuchs Sigismond Bachrich Jules Massenet Margaret Ruthven Lang Frederick Field Bullard George Elbridge Whiting Horatio Parker Ernest Bloch Raissa Myshetskaya Paul Vidal Gabriel Fauré André Gédalge Arnold Schoenberg Théodore Dubois Béla Bartók Vincent -

Espressivo Program Notes April 2018 the Evolution of Chamber Music For

Espressivo Program Notes April 2018 The evolution of chamber music for a mixed ensemble of winds and strings coincides with the domestication of the double bass. Previously used as an orchestral instrument or in dance music, the instrument was admitted into the salon in the late eighteenth century. The granddaddy of the genre is Beethoven’s Septet of 1800, for four strings, clarinet, horn and bassoon. Beethoven seems to have discovered that the largest string instrument, essentially doubling the cello an octave lower and with the capability to play six notes below the lowest note on the bassoon, provided overtones that enhanced the vibrations of the higher instruments. In any case, the popularity of the Septet, which sustains to this day, caused the original players to have a similar work commissioned from Franz Schubert, who added a second violin for his Octet (1824). (Espressivo performed it last season.) It is possible, if not probable, that Schubert’s good friend Franz Lachner wrote his Nonet for the same group, adding a flute, but the origins, and even the date of the composition are in dispute. An indicator might be the highlighting of the virtuosic violin part, as it would have been played by Ignaz Schuppanzigh, who had premiered both the Septet and the Octet. All three works, Septet, Octet and Nonet, have slow introductions to the first and last uptempo movements, and all include a minuet. All seem intended to please rather than to challenge. Beethoven’s Septet was commissioned by a noble patron for the delectation of his guests, as was Schubert’s Octet. -

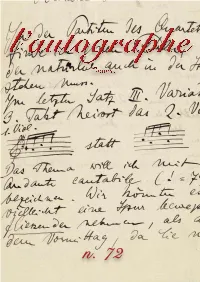

Genève L'autographe

l’autographe Genève l'autographe L’Autographe S.A. 24 rue du Cendrier, CH - 1201, Genève +41 22 510 50 59 (mobile) +41 22 523 58 88 (bureau) web: www.lautographe.com mail: [email protected] All autographs are offered subject to prior sale. Prices are quoted in US DOLLARS, SWISS FRANCS and EUROS and do not include postage. All overseas shipment will be sent by air. Orders above € 1000 benefits of free shipping. We accept payments via bank transfer, PayPal, and all major credit cards. We do not accept bank checks. Postfinance CCP 61-374302-1 3 rue du Vieux-Collège CH-1204, Genève IBAN: EUR: CH94 0900 0000 9175 1379 1 CHF: CH94 0900 0000 6137 4302 1 SWIFT/BIC: POFICHBEXXX paypal.me/lautographe The costs of shipping and insurance are additional. Domestic orders are customarily shipped via La Poste. Foreign orders are shipped with La Poste and Federal Express on request. 1. Richard Adler (New York City, 1921 - Southampton, 2012) Autograph dedication signed on the frontispiece of the musical score of the popular song “Whatever Lola Wants” from the musical comedy “Damn Yankees” by the American composer and producer of several Broadway shows and his partner Jerry Ross. 5 pp. In fine condition. Countersigned with signature and dated “6/2/55” by the accordionist Muriel Borelli. $ 125/Fr. 115/€ 110 2. Franz Allers (Carlsbad, 1905 - Paradise, 1995) Photo portrait with autograph dedication and musical quotation signed, dated June 1961 of the Czech born American conductor of ballet, opera and Broadway musicals. (8 x 10 inch.). In fine condition. -

Richard Strauss

RICHARD STRAUSS: The Origin, Dissemination and Reception of his Mozart Renaissance Raymond lIolden I I \,--,~/ PhD Goldsmiths' College University of London 1 Abstract Richard Strauss holds an important place in the history of performance. Of the major musical figures active during the second half of the nineteenth and the first half of the twentieth centuries, his endeavours as a Mozartian are of particular importance. Strauss' special interest in the works of Mozart was seminal to both his performance and compositional aesthetics. As a result of this affinity, Strauss consciously set out to initiate a Mozart renaissance that embodied a precise set of principles and reforms. It was these principles and reforms, described as literalist, rather than those of artists such .as Gustav Mahler, who edited Mozart's works both musically and dramatically, that found further expression in the readings of, amongst others, Otto Klemperer, George Szell, Sir John Pritchard and Wolfgang Sawallisch. It is the aim of this dissertation to investigate Strauss' activities as a Mozartian and to assess his influence on subsequent generations of Mozart conductors. Accordingly, the dissertation is divided into an Introduction, five chapters, a Conclusion and thirteen appendices. These consider both the nature and ramifications of Strauss' reforms and performance aesthetic. Within this framework, the breadth of his renaissance; his choice of edition, cuts and revisions; his use of tempo, as a means of structural delineation; his activities with respect to the -

Franz Lachner - Hofkapellmeister Und Komponist 79

Zu Unrecht vergessen Künstler im München des 19. und 20. Jahrhunderts Herausgegeben vom Präsidenten und vom Direktorium der Bayerischen Akademie der Schönen Künste WALLSTEIN VERLAG Inhalt Vorwort von Dieter Borchmeyer 7 ALBERT VON SCHIRNDING Georg ßritting - ein süddeutscher Homer 11 MICHAEL SEMFF Oskar Coester - Einzelgänger zwischen Tradition und Moderne 25 HANS-JOACHIM RUCKHÄBERLE Erich Engel - »... der Münchner ist mehr der Vergangenheit zugewandt, als offen für die Zukunft« 43 FRIEDRICH DENK Albrecht Haushofer für die Schule 63 Η ART MUT SCHICK Franz Lachner - Hofkapellmeister und Komponist 79 FR Α Ν Ζ I s ΚΑ D υ Ν Κ Ε L Hermann Landshoff - Karrierebrüche eines Photographen 5 INHALT JENS MALTE FISCHER Mechtilde Lichnowsky - Eine Erinnerung 125 WINFRIED NERDINGER Der Bildhauer und Architekt Hermann Rosa 141 STEPHAN HUΒER Günter Saree - MÖG-LICH 157 HARTWIG LEHR Rudi Stephan - ein vernachlässigter Seitenpfad in der Musik 173 BERND EDELMANN Ludwig Thuille - Komponist im Schatten von Richard Strauss 189 FRIEDHELM KEMP Konrad Weiß - Der Dichter der cumäischen Sibylle 211 Biographische Notizen 225 Bildnachweise 253 6 Franz Lachner April i8oy - 20. Januar 1 HARTMUT SCHICK Franz Lachner - Hofkapellmeister und Komponist Gänzlich vergessen ist der Name Franz Lachner wohl nicht, jedenfalls nicht in München und darüber hinaus im Kreis der dezidiert musikinteressierten Öffentlichkeit. Nicht wenige wissen zumindest noch, daß Franz Lachner ein Holkapellmeister und (eher konservativer) Komponist im München des 19. Jahrhunderts war. Doch viel mehr weiß man über ihn in der Regel nicht, und vor allem kennt man nach wie vor kaum - wenn überhaupt - seine Musik. Nur weniges davon ist auf CD eingespielt, und im heutigen Konzertleben spielt Lachner so gut wie keine Rolle mehr, abgesehen von ein paar Werken für Bläser, den verdienstvollen Bemühungen des Münchner Rodin- Quartetts um seine Streichquartette oder dem Bereich des Männerchorwesens, wo Lachner nach wie vor eine feste Größe ist. -

Music Manuscripts and Books Checklist

THE MORGAN LIBRARY & MUSEUM MASTERWORKS FROM THE MORGAN: MUSIC MANUSCRIPTS AND BOOKS The Morgan Library & Museum’s collection of autograph music manuscripts is unequaled in diversity and quality in this country. The Morgan’s most recent collection, it is founded on two major gifts: the collection of Mary Flagler Cary in 1968 and that of Dannie and Hettie Heineman in 1977. The manuscripts are strongest in music of the eighteenth, nineteenth, and early twentieth centuries. Also, the Morgan has recently agreed to purchase the James Fuld collection, by all accounts the finest private collection of printed music in the world. The collection comprises thousands of first editions of works— American and European, classical, popular, and folk—from the eighteenth century to the present. The composers represented in this exhibition range from Johann Sebastian Bach to John Cage. The manuscripts were chosen to show the diversity and depth of the Morgan’s music collection, with a special emphasis on several genres: opera, orchestral music and concerti, chamber music, keyboard music, and songs and choral music. Recordings of selected works can be heard at music listening stations. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791) Der Schauspieldirektor, K. 486. Autograph manuscript of the full score (1786). Cary 331. The Mary Flagler Cary Music Collection. Mozart composed this delightful one-act Singspiel—a German opera with spoken dialogue—for a royal evening of entertainment presented by Emperor Joseph II at Schönbrunn, the royal summer residence just outside Vienna. It took the composer a little over two weeks to complete Der Schauspieldirektor (The Impresario). The slender plot concerns an impresario’s frustrated attempts to assemble the cast for an opera. -

Der Fliegende Holländer

RICHARD WAGNER der fliegende holländer conductor Opera in three acts Valery Gergiev Libretto by the composer, based on the production François Girard novel Aus den Memoiren des Herren von Schnabelewopski by Heinrich Heine set designer John Macfarlane Monday, March 2, 2020 costume designer 8:00–10:25 PM Moritz Junge lighting designer New Production Premiere David Finn projection designer Peter Flaherty The production of Der Fliegende Holländer choreographer was made possible by a generous gift Carolyn Choa from Veronica Atkins dramaturg Serge Lamothe general manager Peter Gelb A co-production of the Metropolitan Opera; jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Dutch National Opera, Amsterdam; The Abu Dhabi Yannick Nézet-Séguin Festival; and Opéra de Québec 2019–20 SEASON The 160th Metropolitan Opera performance of RICHARD WAGNER’S der fliegende holländer conductor Valery Gergiev in order of vocal appearance daland Franz-Josef Selig steersman David Portillo dutchman Evgeny Nikitin mary Mihoko Fujimura DEBUT senta Anja Kampe DEBUT erik Sergey Skorokhodov This performance is being broadcast live on Metropolitan senta dancer Opera Radio on Alison Clancy SiriusXM channel 75 and streamed at metopera.org. Der Fliegende Holländer is performed without intermission. Monday, March 2, 2020, 8:00–10:25PM KEN HIOWARD / MET OPERA A scene Chorus Master Donald Palumbo from Wagner’s Interactive Video Development Jesse Garrison / Der Fliegende Nightlight Labs Holländer Associate Video Producer Terry Gilmore Musical Preparation John Keenan, Dan Saunders, Bradley -

HOLLIS, DEBORAH LEE, DMA Orchestral Color in Richard Strauss's Lieder

HOLLIS, DEBORAH LEE, D.M.A. Orchestral Color in Richard Strauss’s Lieder: Enhancing Performance Choices of All of Strauss’s Lieder through a Study of His Orchestrated Lieder. (2009) Directed by Dr. James Douglass. 83 pp. Strauss was a major composer of Lieder , with more than 200 published songs composed between 1870 and 1948, many of which belong to the standard song repertoire. Strauss’s lieder are distinctive because they reflect his simultaneous preoccupation with composing tone poems and operas. The vocal lines are declamatory, dramatic, and lyrical, while the accompaniments are richly textured. Strauss learned the craft of orchestration through studying scores of the masters, playing in orchestras, conducting, and through exposure to prominent composers. Equally important was his affiliation with leading figures of the New German School including Liszt, Wagner, and Berlioz. Berlioz used the expressive characteristics of the orchestral instruments as the primary inspiration for his compositions. Like Berlioz, Strauss used tone color as a crucial element that gave expression to poetic ideas in his symphonic works, operas, and songs. Strauss’s approach to orchestration gives insight into ways that a collaborative pianist may use tone color to enhance renderings of all of the composer’s lieder. In this study, I use my own analysis of Strauss’s orchestrations of his songs, as well as Strauss’s statements in his revision of Berlioz’s Treatise on Instrumentation , to show how his orchestrations bring out important aspects of the songs, clarifying and enriching their meaning. I further show how collaborative pianists can emulate these orchestral effects at the keyboard using specific techniques of touch, pedal, and phrasing, thereby rendering each song richer and more meaningful. -

Consortium Classicum

Große Kammermusik Samstag 12. Januar 2013, 18 Uhr, Fiskina Fischen Consortium classicum Gunhild Ott, Flöte Andreas Krecher, Violine Pavel Sokolov, Oboe Niklas Schwarz, Viola Manfred Lindner, Klarinette Armin Fromm, Cello Helman Jung, Fagott Jürgen Normann, Kontrabass Jan Schröder, Horn Programm: Louis Spohr Gran Nonetto, F-Dur, op.31 (1819) W. A. Mozart Flötenquartett D-Dur, KV 285 (1777/78) Franz Lachner Nonett F-Dur, (1875) `Hommage à Franz Schubert´ 29 Mit der Grundung des Consortium Classicum betrat vor Darüber hinaus wird die Arbeit des CC durch ein hausei- etwa fünfzig Jahren ein deutsches Kammerensemble die genes Musikarchiv unterstützt, welches exklusiv einen Musikszene, um in variabler Besetzung, neben der selbst- reichhaltigen Bestand an Werken zu Unrecht vergessener verständlichen Pflege des Standardrepertoires auch zahl- Meister des 18. und 19. Jahrhunderts beinhaltet. Dieses reiche wiederentdeckte Musikschätze lebendig werden zu Archiv, das seit Jahrzehnten der Grundlagenforschung lassen. Initiator war der inzwischen verstorbene verpflichtet ist, garantiert, daß auch in Zukunft auf CD, Klarinettist Dieter Klöcker, der bis zu zehn Solisten, im Fernsehen und selbstverständlich ganz besonders im Hochschulprofessoren und Stimmfuhrer aus Konzertleben die Breite der künstlerischen Aussagen und Spitzenorchestern um sich scharte und mit ihnen den die Qualität der Ausfuhrungen auf hohem Niveau Ensemblegedanken in einer sehr eigenen und konsequen- gewährleistet ist. ten Form pflegte. Diese Vielfalt von solistischem Können, Ensemblegeist Eine internationale Konzerttätigkeit sowie zahlreiche und Forschung bestätigt den exzeptionellen Rang dieses ehrenvolle Auszeichnungen und Einladungen zu promi- in jeder Hinsicht einzigartigen Ensembles. nenten Festivals, wie den Salzburger Festspielen oder den Festwochen in Wien und Berlin, brachten dem Ensemble Pavel Sokolov, Oboe, lernte ab 1981 bei Sergej Burdukov weltweite Anerkennung. -

Download Booklet

THE CAPTIVE NIGHTINGALE Nineteenth century art song was firmly harnessed That much of the music on this disc was long to the instrument found in every genteel forgotten is symptomatic of the neglect of this GERMAN ROMANTIC RARITIES home – the piano. Other available players were repertoire. A ‘Lieder recital’ gradually established FOR SOPRANO, CLARINET & PIANO eagerly welcomed to the salon and editions were itself in the concert hall rather than the published with ad libitum or obbligato parts household, predominantly with voice and piano for violin, flute, horn, cello, harmonium, and the alone, and the twentieth century turned a instrument outstandingly raised in status by largely deaf ear to the perceived sentimentality 1 Alpenlied | Song of the Alps Andreas Späth (1792-1876) [3.31] Mozart and Weber, and well suited in range and or Biedermeier qualities of ‘salon music’. 2 Das Mühlrad | The Mill-Wheel Conradin Kreutzer (1780-1849) [5.06] tone colour – the clarinet. The winning combination Discovering items long overlooked can bring 3 Schweitzers Heimweh | Homesick for Switzerland Heinrich Proch (1809-1878) [5.00] of voice, clarinet and piano delighted intimate many rewards. One item in this recital, the 4 Die gefangene Nachtigall | The Captive Nightingale * Heinrich Proch [5.02] gatherings and inspired many lovely works. iconic song for this combination, Schubert’s 5 Heimathlied | Home Song Johann Baptist Wenzel Kalliwoda (1801-1866) [4.03] Shepherd on the Rock, has always been admired 6 Seit ich ihn gesehen | Ever Since I Saw Him Franz Lachner (1803-1890) [4.54] Musical history owes much to clarinettists and performed, and exerted its influence in whose talents stimulated a series of subject matter and style on others heard here. -

Here Better Than in the Sonata for Two Pianos in F Minor

BRONFMAN & MCDERMOTT THURSDAY, AUGUST 6, 2020 GERALD R. FORD AMPHITHEATER CONCERT 7 PM Yefim Bronfman, piano Anne-Marie McDermott, piano SCHUBERT Marche Militaire in D major for Piano, Four Hands, D. 733, No. 1 (5 minutes) SCHUBERT Fantasy in F minor for Piano, Four Hands, D. 940 (19 minutes) Allegro molto moderato — Largo — Allegro vivace — Tempo I BRAHMS Sonata in F minor for Two Pianos, Op. 34b (35 minutes) (piano version of the Quintet for Piano, Two Violins, Viola and Cello, Op. 34) Allegro non troppo Andante, un poco adagio Scherzo: Allegro Finale: Poco sostenuto — Allegro non troppo Marche Militaire in D major for Piano, Four Hands, D. 733, No. 1 (1818) Franz Schubert (1797-1828) In June 1816, when he was nineteen, Schubert received his first fee for one of his compositions (a now-lost cantata for the name-day of his teacher, Heinrich Watteroth), and decided that he had sufficient reason to leave his irksome teaching post at his father’s school in order to follow the life of an artist. He moved into the Viennese apartments of his devoted friend Franz von Schober, an Austrian civil servant who was then running the state lottery, and celebrated his new freedom by composing incessantly, rising shortly after dawn (sometimes he slept with his glasses on so as not to waste any time getting started in the morning), pouring out music until early afternoon, and then spending the evening haunting the cafés of Grinzing or making music with friends. Those convivial soirées became more frequent and drew increasing notice during the following months, and they were the principal means by which Schubert’s works became known to the city’s music lovers. -

7 X 11 Long.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-72815-7 - The Cambridge Companion to Richard Strauss Edited by Charles Youmans Excerpt More information Part I Background © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-72815-7 - The Cambridge Companion to Richard Strauss Edited by Charles Youmans Excerpt More information 1 The musical world of Strauss’s youth James Deaville Born in Munich on June 11, 1864, Richard Strauss entered the world at a crucial time of change for the political and cultural environment in which he would develop as person and musician: three months earlier, Ludwig II had acceded to power over the Kingdom of Bavaria, while almost six weeks earlier, Richard Wagner had first arrived in Munich under the new king’s aegis. That these related events did not have an immedi- ate impact on Strauss in his earliest years does not diminish their ultim- ate real and symbolic significance for his life and career: he emerged as musician within a city where the revolution in music was a matter of public debate, especially to the extent that its progenitor Wagner dir- ectly influenced the monarch and indirectly had an impact on affairs of state. Character of the city However, of all German-speaking major cities, Munich may have been the least suited for artistic upheaval, given the nature of its institutions and the character of its citizens. In his study Pleasure Wars, Peter Gay paints a picture of a Munich that was hopelessly polarized, between the cultural offerings sponsored by the ruling Wittelsbachs and the middle class that preferred popular types of entertainment.1 Notably absent during the reigns of Ludwig I, Maximilian II, and Ludwig II was a significant bour- geois involvement in the higher forms of art, which Gay attributes in part to what he calls the “habitual passivity” of Munich’s Bürger,2 formed by a nexus of the monarch’s paternalist attitude towards his subjects and the residents’ appetite for amusement.