Indraprasth 2016-17

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Essence of Sanatsujatiya of Maha Bharata

ESSENCE OF SANATSUJATIYA OF MAHA BHARATA Translated, interpreted and edited by V.D.N.Rao 1 Other Scripts by the same Author: Essence of Puranas:-Maha Bhagavata, Vishnu, Matsya, Varaha, Kurma, Vamana, Narada, Padma; Shiva, Linga, Skanda, Markandeya, Devi Bhagavata;Brahma, Brahma Vaivarta, Agni, Bhavishya, Nilamata; Shri Kamakshi Vilasa- Dwadasha Divya Sahasranaama:a) Devi Chaturvidha Sahasra naama: Lakshmi, Lalitha, Saraswati, Gayatri;b) Chaturvidha Shiva Sahasra naama-Linga-Shiva-Brahma Puranas and Maha Bhagavata;c) Trividha Vishnu and Yugala Radha-Krishna Sahasra naama-Padma-Skanda-Maha Bharata and Narada Purana. Stotra Kavacha- A Shield of Prayers -Purana Saaraamsha; Select Stories from Puranas Essence of Dharma Sindhu - Dharma Bindu - Shiva Sahasra Lingarchana-Essence of Paraashara Smriti- Essence of Pradhana Tirtha Mahima- Essence of Ashtaadasha Upanishads: Brihadarankya, Katha, Taittiriya/ Taittiriya Aranyaka , Isha, Svetashvatara, Maha Narayana and Maitreyi, Chhadogya and Kena, Atreya and Kausheetaki, Mundaka, Maandukya, Prashna, Jaabaala and Kaivalya. Also ‗Upanishad Saaraamsa‘ - Essence of Virat Parva of Maha Bharata- Essence of Bharat Yatra Smriti -Essence of Brahma Sutras- Essence of Sankhya Parijnaana- Essence of Knowledge of Numbers for students-Essence of Narada Charitra; Essence Neeti Chandrika-Essence of Hindu Festivals and AusteritiesEssence of Manu Smriti- Quintessence of Manu Smriti- Essence of Paramartha Saara; Essence of Pratyaksha Bhaskra; Essence of Pratyaksha Chandra; Essence of Vidya-Vigjnaana-Vaak Devi; Essence -

Siyahi-Catalogue-2015-16.Pdf

Siyahi, in Urdu means ‘ink’, the dye that stains the shape of our thoughts. Tell us your story. And we’ll help you tell it to the world. Here at Siyahi, we’re with you right from the beginning. From assessing and editing the manuscript to finding the right publisher and promoting the book after publication, we stand firm by our authors through it all. While we deal primarily with manuscripts in English, we are actively involved in facilitating translation of books to and from various languages. We also organize literary events – everything from intimate readings to international literary festivals. RIGHTS LIST ALL RIGHTS AVAILABLE WORLD RIGHTS AVAILABLE LANGUAGE RIGHTS AVAILBLE AUTHORS FORTHCOMING PUBLISHED EVENTS TEAM RIGHTS LIST ALL RIGHTS AVAILABLE FICTION All Our Days by Keya Ghosh An Excess of Sanity by Anshumani Ruddra In Another Time by Keya Ghosh Indophrenia by Sudeep Chakravarti Men Without God by Meghna Pant Mohini’s Wedding by Selina Hossain (English Translation by Arunava Sinha) No More Tomorrows by Keya Ghosh Poskem by Wendell Rodricks The Ceaseless Chatter of Demons by Ashok Ferrey You Who Never Arrived by Anshumani Ruddra NON-FICTION Dream Catchers: Business Innovators of Bollywood by Priyanka Sinha Jha Dream Moghuls: Business Leaders of Bollywood by Priyanka Sinha Jha Folk Music and Musical Instruments of Punjab by Alka Pande Indian Street Food by Rocky Singh, Mayur Sharma Like Cotton from the Kapok Tree by Kalpana Mohan Managing Success...and Some Seriously Good Food by Rocky Singh, Mayur Sharma Magician in the Desert -

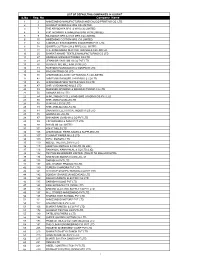

S.No Reg. No Company Name 1 2 AHMEDABAD MANUFACTURING and CALICO PRINTING CO

LIST OF DEFAULTING COMPANIES IN GUJRAT S.No Reg. No Company_Name 1 2 AHMEDABAD MANUFACTURING AND CALICO PRINTING CO. LTD. 2 3 GUJARAT GINNING & MFG CO.LIMITED. 3 7 THE ARYODAYA SPG & WVG.CO.LIMITED. 4 8 40817HCHOWK & AHMEDABAD MFG CO.LIMITED. 5 9 RAJNAGAR SPG & WVG MFG.CO.LIMITED. 6 10 HMEDABAD COTTON MFG. CO.LIMITED. 7 12 12DISPLAY STATUSSTEEL INDUSTRIES PVT. LTD. 8 18 ISHWER COTTON G.N.& PRES.CO.LIMITED. 9 22 THE AHMEDABAD NEW COTTON MILLS CO.LIMITED. 10 25 BHARAT KHAND TEXTILE MANUFACTURING CO LTD 11 27 HIMABHAI MANUFACTURING CO LTD 12 29 JEHANGIR VAKIL MILLS CO PVT LTD 13 30 GUJARAT OIL MILL & MFG CO LTD 14 31 RUSTOMJI MANGALDAS & COMPANY LTD 15 34 FINE KNITTING CO LTD 16 40 AHMEDABAD LAXMI COTTON MILLS CO.LIMITED. 17 42 AHMEDABAD KAISER-I-HIND MILLS CO LTD 18 45 AHMEDABAD NEW TEXTILE MILS CO LTD 19 47 SHRI VIVEKANAND MILLS LTD 20 49 MARSDEN SPINNING & MANUFACTURING CO LTD 21 50 ASHOKA MILLS LTD. 22 54 AHMEDABAD CYCLE & MOTORS TRADING CO PVT LTD 23 68 SHRI AMRUTA MILLS LTD 24 78 VIJAY MILLS CO LTD 25 79 SHRI ARBUDA MILLS LTD. 26 81 DHARWAR ELECTRICAL INDUSTRIES LTD 27 85 ANANTA MILLS LTD 28 87 BHIKABHAI JIVABHAI & CO PVT LTD 29 89 J R VAKHARIA & SONS PVT LTD 30 99 BIHARI MILLS LIMITED 31 101 ROHIT MILLS LTD 32 106 AHMEDABAD FIBRE-SALES & SUPPLIES LTD 33 107 GUJARAT PAPER MILLS LTD 34 109 IDEAL MOTORS LTD 35 110 MODEL THEATRES PVT LTD 36 115 HIMATLAL MOTILAL & CO LTD.(IN LIQ.) 37 116 RAMANLAL KANAIYALAL & CO LTD.(LIQ). -

Kunti, Satyavati's Grand

unti, Satyavati’s grand- Part III: Five Holy Virgins, Five Sacred Myths daughter-in-law, is a remarkable study in K 1 womanhood. Kunti chooses the handsome Pandu in a bridegroom- “One-in Herself” choice ceremony, svayamvara, only to find Bhishma snatching away her Why Kunti Remains a Kanya happiness by marrying him off again immediately to the captivating Madri. Pradip Bhattacharya She insists on accompanying her husband into exile and faces a horripilating situation: her beloved husband insists that she get son after In the first two parts of this quest we have explored two of son for him by others. It is in this 2 the five kanyas, Ahalya and Mandodari of the Ramayana, husband-wife encounter that Kunti’s seeking to understand what makes them such remarkable individuality shines forth. At first she women, as well as describe what special features firmly refuses saying, “Not even in characterise all these kanyas.We are now entering the dense thought will I be embraced by another (I.121.5).” forest of the Mahabharata to discuss Kunti. To help the Her statement is somewhat readers through its thickly interwoven maze of relationships, devious, as already she has embraced I have provided the broad linkages of these characters in a Surya and regained virgin status by separate box (see opposite page).* virtue of his boon after delivering Karna. It is, however, evidence of her and tries to persuade her urging that Shvetaketu’s scriptural directive for resolve to maintain an unsullied (a) she will only be doing what is implicitly obeying the husband’s reputation. -

Essence of Valmiki Ramayana in Four Parts So Far of Baala-Ayodhya-Aranya- and Now the Kishkindha

ESSENCE OF VALMIKI KISHKINDHA RAMAYANA Translated and interpreted byV.D.N.Rao, former General Manager, India Trade Promotion Organization, Ministry of Commerce, Govt. of India, Pragati Maidan, New Delhi, now at Chennai 1 Other Scripts by the same Author: Essence of Puranas:-Maha Bhagavata, Vishnu Purana, Matsya Purana, Varaha Purana, Kurma Purana, Vamana Purana, Narada Purana, Padma Purana; Shiva Purana, Linga Purana, Skanda Purana, Markandeya Purana, Devi Bhagavata;Brahma Purana, Brahma Vaivarta Purana, Agni Purana, Bhavishya Purana, Nilamata Purana; Shri Kamakshi Vilasa Dwadasha Divya Sahasranaama: a) Devi Chaturvidha Sahasra naama: Lakshmi, Lalitha, Saraswati, Gayatri; b) Chaturvidha Shiva Sahasra naama-Linga-Shiva-Brahma Puranas and Maha Bhagavata; c) Trividha Vishnu and Yugala Radha-Krishna Sahasra naama-Padma-Skanda- Maha Bharata and Narada Purana. Stotra Kavacha- A Shield of Prayers -Purana Saaraamsha; Select Stories from Puranas Essence of Dharma Sindhu - Dharma Bindu - Shiva Sahasra Lingarchana-Essence of Paraashara Smriti- Essence of Pradhana Tirtha Mahima Essence of Upanishads : Brihadaranyaka , Katha, Tittiriya, Isha, Svetashwara of Yajur Veda- Chhandogya and Kena of Saama Veda-Atreya and Kausheetaki of Rig Veda-Mundaka, Mandukya and Prashna of Atharva Veda ; Also ‘Upanishad Saaraamsa’ -Essence of Maha Narayanopanishad; Essence of Maitri Upanishad Essence of Virat Parva of Maha Bharata- Essence of Bharat Yatra Smriti Essence of Brahma Sutras Essence of Sankhya Parijnaana- Essence of Knowledge of Numbers for students Essence -

(Bharatavarsha) Zur Zeit Des Mahabharata / Ramayana 68° 70° 72° 74° 76° 78° 80° 82° 84° 86° 88° 90°

Das historische Indien (Bharatavarsha) zur Zeit des Mahabharata / Ramayana 68° 70° 72° 74° 76° 78° 80° 82° 84° 86° 88° 90° N 38° W O 38° Huna Saka S Bahlika Ramatha 8611 36° Darada 36° Bharata besiegt Gandhara Kamboja Mt.Godwin C Harahuna Nishkuta Kapisa 8126 H Skardu (O) Naubandhana I Uraga Kala Yavana Aroosa N Pahlava Yavana Gandhara (N) Yoni Abhisara Varaha Rishika Kabul A Kirata Pushkalavati Khuba Avisari Kasmira Loha Charsadda S Peshawar LohaSindhu (Indus) 34° Parasika Purushapura Takshashila 34° Islamabad (W Sweta Uttara-Jyotisha Kamboja Naga eißer Berg) Suhma Rajavasa Mahetta Reise zum Sweta, Gandhamadanum Arjuna zu treffen Utsava-Sanketa Sumala Amara Pisacha Kekaya ist das Königreich itashta von Bharatas Mutter Kaikeyi V Chandrabhaga Bhalika MBH3.130 Kekaya Hidimba Kimpurusha Dasarna Asikini MBH3.139 Madra Vipasa/Arjikia Kinnara 32° 32° Madhyamakeyas Sakala MBH3.177 Karnata Iravati Trigarta Vadava V Divyakutta Lahore isakhayupa Hemakuta Bhishma erobert Yamunotri Kulinda 19 (Yaksha) Sivi Matta- Madri für Pandu 6656 6040Bhrigutunga Mayuraka Harataka Kailash Arjunas Feldzug Dwarapala Vadari MBH1.1 HarappaTurvasa Bhagirati (Mandara) nach Norden MBH1.1 Vatadhana Parushni Belehrung des MBH3.140 ipasa 13 Manasa Arjunas Exil Mandakini V MBH3.37 MBH3.177MBH2.26 Lackhaus Markandeya im Wald Ganga Satadru Sarasvati Varanavata Saraswata Samantapanchaka Rishikesh Pandus Rückzug K 30° Gangadwara Saugandhika 30° Kamyaka MBH3.5 ChaitrarathaHaridwar in den Wald Sindhu Malava Feldzug nach Kurukshetra I Amvasta Kuru 14 Usinara R MBH1.141 MBH1.1 der -

Pancha Maha Bhutas (Earth-Water-Fire-Air-Sky)

1 ESSENCE OF PANCHA MAHA BHUTAS (EARTH-WATER-FIRE-AIR-SKY) Compiled, composed and interpreted by V.D.N.Rao, former General Manager, India Trade Promotion Organisation, Pragati Maidan, New Delhi, Ministry of Commerce, Govt. of India, now at Chennai. Other Scripts by the same Author: Essence of Puranas:-Maha Bhagavata, Vishnu Purana, Matsya Purana, Varaha Purana, Kurma Purana, Vamana Purana, Narada Purana, Padma Purana; Shiva Purana, Linga Purana, Skanda Purana, Markandeya Purana, Devi Bhagavata;Brahma Purana, Brahma Vaivarta Purana, Agni Purana, Bhavishya Purana, Nilamata Purana; Shri Kamakshi Vilasa Dwadasha Divya Sahasranaama: a) Devi Chaturvidha Sahasra naama: Lakshmi, Lalitha, Saraswati, Gayatri; b) Chaturvidha Shiva Sahasra naama-Linga-Shiva-Brahma Puranas and Maha Bhagavata; c) Trividha Vishnu and Yugala Radha-Krishna Sahasra naama-Padma-Skanda-Maha Bharata and Narada Purana. Stotra Kavacha- A Shield of Prayers -Purana Saaraamsha; Select Stories from Puranas Essence of Dharma Sindhu - Dharma Bindu - Shiva Sahasra Lingarchana-Essence of Paraashara Smriti Essence of Pradhana Tirtha Mahima Essence of Upanishads : Brihadaranyaka , Katha, Tittiriya, Isha, Svetashwara of Yajur Veda-Chhandogya and Kena of Saama Veda-Atreya and Kausheetaki of Rig Veda-Mundaka, Mandukya and Prashna of Atharva Veda ; Also ‗Upanishad Saaraamsa‘ (Quintessence of Upanishads) Essence of Virat Parva of Maha Bharata- Essence of Bharat Yatra Smriti Essence of Brahma Sutras Essence of Sankhya Parijnaana- Also Essence of Knowledge of Numbers Essence of Narada Charitra; Essence Neeti Chandrika-Essence of Hindu Festivals and Austerities Essence of Manu Smriti- Quintessence of Manu Smriti- Essence of Paramartha Saara; Essence of Pratyaksha Bhaskra; Essence of Maha Narayanopashid; Essence of Maitri Upanishad Essence of Vidya-Vigjnaana-Vaak Devi; Essence of Bhagya -Bhogya-Yogyata Lakshmi Essence of Soundarya Lahari*- Essence of Popular Stotras*- Essence of Pratyaksha Chandra*- Essence of Pancha Bhutas* Note: All the above Scriptures already released on www. -

Indian Serpent Lore Or the Nagas in Hindu Legend And

D.G.A. 79 9 INDIAN SERPENT-LOEE OR THE NAGAS IN HINDU LEGEND AND ART INDIAN SERPENT-LORE OR THE NAGAS IN HINDU LEGEND AND ART BY J. PH. A'OGEL, Ph.D., Profetsor of Sanskrit and Indian Archirology in /he Unircrsity of Leyden, Holland, ARTHUR PROBSTHAIN 41 GREAT RUSSELL STREET, LONDON, W.C. 1926 cr," 1<A{. '. ,u -.Aw i f\0 <r/ 1^ . ^ S cf! .D.I2^09S< C- w ^ PRINTED BY STEPHEN AUSTIN & SONS, LTD., FORE STREET, HERTFORD. f V 0 TO MY FRIEND AND TEACHER, C. C. UHLENBECK, THIS VOLUME IS DEDICATED. PEEFACE TT is with grateful acknowledgment that I dedicate this volume to my friend and colleague. Professor C. C. Uhlenbeck, Ph.D., who, as my guru at the University of Amsterdam, was the first to introduce me to a knowledge of the mysterious Naga world as revealed in the archaic prose of the Paushyaparvan. In the summer of the year 1901 a visit to the Kulu valley brought me face to face with people who still pay reverence to those very serpent-demons known from early Indian literature. In the course of my subsequent wanderings through the Western Himalayas, which in their remote valleys have preserved so many ancient beliefs and customs, I had ample opportunity for collecting information regarding the worship of the Nagas, as it survives up to the present day. Other nations have known or still practise this form of animal worship. But it would be difficult to quote another instance in which it takes such a prominent place in literature folk-lore, and art, as it does in India. -

Bhagavad Geeta – 10

|| ´ÉÏqÉ°aÉuɪÏiÉÉ || BHAGAVAD GEETA – 10 The YogaTEXT of 00 Divine Glories “THE SANDEEPANY EXPERIENCE” Reflections by SWAMI GURUBHAKTANANDA TEXT 28.10 Sandeepany’s Vedanta Course List of All the Course Texts in Chronological Sequence: Text TITLE OF TEXT Text TITLE OF TEXT No. No. 1 Sadhana Panchakam 24 Hanuman Chalisa 2 Tattwa Bodha 25 Vakya Vritti 3 Atma Bodha 26 Advaita Makaranda 4 Bhaja Govindam 27 Kaivalya Upanishad 5 Manisha Panchakam 28.10 Bhagavad Geeta (Discourse 10 ) 6 Forgive Me 29 Mundaka Upanishad 7 Upadesha Sara 30 Amritabindu Upanishad 8 Prashna Upanishad 31 Mukunda Mala (Bhakti Text) 9 Dhanyashtakam 32 Tapovan Shatkam 10 Bodha Sara 33 The Mahavakyas, Panchadasi 5 11 Viveka Choodamani 34 Aitareya Upanishad 12 Jnana Sara 35 Narada Bhakti Sutras 13 Drig-Drishya Viveka 36 Taittiriya Upanishad 14 “Tat Twam Asi” – Chand Up 6 37 Jivan Sutrani (Tips for Happy Living) 15 Dhyana Swaroopam 38 Kena Upanishad 16 “Bhoomaiva Sukham” Chand Up 7 39 Aparoksha Anubhuti (Meditation) 17 Manah Shodhanam 40 108 Names of Pujya Gurudev 18 “Nataka Deepa” – Panchadasi 10 41 Mandukya Upanishad 19 Isavasya Upanishad 42 Dakshinamurty Ashtakam 20 Katha Upanishad 43 Shad Darshanaah 21 “Sara Sangrah” – Yoga Vasishtha 44 Brahma Sootras 22 Vedanta Sara 45 Jivanmuktananda Lahari 23 Mahabharata + Geeta Dhyanam 46 Chinmaya Pledge A NOTE ABOUT SANDEEPANY Sandeepany Sadhanalaya is an institution run by the Chinmaya Mission in Powai, Mumbai, teaching a 2-year Vedanta Course. It has a very balanced daily programme of basic Samskrit, Vedic chanting, Vedanta study, Bhagavatam, Ramacharitmanas, Bhajans, meditation, sports and fitness exercises, team-building outings, games and drama, celebration of all Hindu festivals, weekly Gayatri Havan and Guru Paduka Pooja, and Karma Yoga activities. -

Raman Women in India a Social and Cultural History

Women in India India Physical Map Courtesy of Natraj A. Raman Women in India A Social and Cultural History Volume 1 SITA ANANTHA RAMAN PRAEGER An Imprint of ABC-CLIO, LLC Copyright 2009 by Sita Anantha Raman All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Raman, Sita Anantha. Women in India : a social and cultural history / Sita Anantha Raman. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978 0 275 98242 3 (hard copy (set) : alk. paper) ISBN 978 0 313 37710 5 (hard copy (vol. 1) : alk. paper) ISBN 978 0 313 37712 9 (hard copy (vol. 2) : alk. paper) ISBN 978 0 313 01440 6 (ebook (set)) ISBN 978 0 313 37711 2 (ebook (vol. 1)) ISBN 978 0 313 37713 6 (ebook (vol. 2)) 1. Women India. 2. Women India Social conditions. I. Title. HQ1742.R263 2009 305.48’891411 dc22 2008052685 131211100912345 This book is also available on the World Wide Web as an eBook. Visit www.abc clio.com for details. ABC CLIO, LLC 130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911 Santa Barbara, California 93116 1911 This book is printed on acid free paper Manufactured in the United States of America YOKED OXEN Pipes played, drums rolled the chant of mantras cleansed the air as showered with flowers we took seven steps together, you and I two oxen, one yoke Since that day pebbles on my path became petals on a rug For dear Babu CONTENTS Volume 1: Early India Preface ix Introduction xi Abbreviations xxi 1. -

Indian Histriography-Vedic and Puranic Perceptions Sumer Khajuria Advocate

IJARSCT ISSN (Online) 2581-9429 ISSN (Print) 2581-XXXX International Journal of Advanced Research in Science, Communication and Technology (IJARSCT) Volume 2, Issue 2, February 2021 Impact Factor: 4.819 Indian Histriography-Vedic and Puranic Perceptions Sumer Khajuria Advocate Abstract: Etymology attested to by Panini indicates. “Itihasa” to mean “Thus indeed in this tradition”. Chankya’s Artshastra defines “Itihasa” as Purana (the chronicles of ancients); Itivarta (history), Akhyayika (tales), Udhaaharana (Illustrative stories), Dharma Shastra (the canon of righteous conduct) are known by history, (comprise corpus of Itihasa).1 According to Mahabharata which itself considered to be Itihasa, a knowledge of Itihasa and Purana is essential to the proper understanding the veda.2 Thus Mahabarta and Manu-Samhita states “One should compliment one’s understanding of the Vedas with the of Itihasa and Puranas likewise Puran as are called by that name because they are complete. I. INTRODUCTION It is an endeavour in writing the history especially writing of such history based on the critical examination of sources, by selection of particular details from the authentic materials in these sources and the sysnthesis of those details into a narrative that stands in the test of critical examination. The term hisrorigraphy also refers to the theory and history of history writing. Webster’s Encyclopedic unbrideged Dictionary of the English Language defines “Historiography” as the body of literature dealing with historical matters; histories collectively, the body of techniques, Theories and principles of historical scholarship; the narrative presentation of history based on a critical examination, evaluation and selection of material from primary, secondary sources and subject to scholarly criteria3. -

Women, Serpent and Devil: Female Devilry in Hindu and Biblical Myth and Its Cultural Representation: a Comparative Study Suman Chakraborty

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 18 | Issue 2 Article 11 Jan-2017 Women, Serpent and Devil: Female Devilry in Hindu and Biblical Myth and its Cultural Representation: A Comparative Study Suman Chakraborty Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Hindu Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Chakraborty, Suman (2017). Women, Serpent and Devil: Female Devilry in Hindu and Biblical Myth and its Cultural Representation: A Comparative Study. Journal of International Women's Studies, 18(2), 156-165. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol18/iss2/11 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2017 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Women, Serpent and Devil: Female Devilry in Hindu and Biblical Myth and its Cultural Representation: A Comparative Study Suman Chakraborty1 Abstract Association of Women with Serpent and Devil or evil is common in today’s popular movies and literature. A large number of movies have been made on serpent woman, or Nagin- Kanya, both in India and the West in the last century. But the root of this popular trend lies in Genesis of the Bible, and its interpretations by the theologians and the church fathers. In India, this motif came with British literary and cultural products through colonization.