Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maharashtra Tourism Development Corporation Ltd., Mumbai 400 021

WEL-COME TO THE INFORMATION OF MAHARASHTRA TOURISM DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION LIMITED, MUMBAI 400 021 UNDER CENTRAL GOVERNMENT’S RIGHT TO INFORMATION ACT 2005 Right to information Act 2005-Section 4 (a) & (b) Name of the Public Authority : Maharashtra Tourism Development Corporation (MTDC) INDEX Section 4 (a) : MTDC maintains an independent website (www.maharashtratourism. gov.in) which already exhibits its important features, activities & Tourism Incentive Scheme 2000. A separate link is proposed to be given for the various information required under the Act. Section 4 (b) : The information proposed to be published under the Act i) The particulars of organization, functions & objectives. (Annexure I) (A & B) ii) The powers & duties of its officers. (Annexure II) iii) The procedure followed in the decision making process, channels of supervision & Accountability (Annexure III) iv) Norms set for discharge of functions (N-A) v) Service Regulations. (Annexure IV) vi) Documents held – Tourism Incentive Scheme 2000. (Available on MTDC website) & Bed & Breakfast Scheme, Annual Report for 1997-98. (Annexure V-A to C) vii) While formulating the State Tourism Policy, the Association of Hotels, Restaurants, Tour Operators, etc. and its members are consulted. Note enclosed. (Annexure VI) viii) A note on constituting the Board of Directors of MTDC enclosed ( Annexure VII). ix) Directory of officers enclosed. (Annexure VIII) x) Monthly Remuneration of its employees (Annexure IX) xi) Budget allocation to MTDC, with plans & proposed expenditure. (Annexure X) xii) No programmes for subsidy exists in MTDC. xiii) List of Recipients of concessions under TIS 2000. (Annexure X-A) and Bed & Breakfast Scheme. (Annexure XI-B) xiv) Details of information available. -

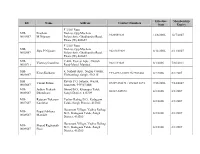

District Taluka Center Name Contact Person Address Phone No Mobile No

District Taluka Center Name Contact Person Address Phone No Mobile No Mhosba Gate , Karjat Tal Karjat Dist AHMEDNAGAR KARJAT Vijay Computer Education Satish Sapkal 9421557122 9421557122 Ahmednagar 7285, URBAN BANK ROAD, AHMEDNAGAR NAGAR Anukul Computers Sunita Londhe 0241-2341070 9970415929 AHMEDNAGAR 414 001. Satyam Computer Behind Idea Offcie Miri AHMEDNAGAR SHEVGAON Satyam Computers Sandeep Jadhav 9881081075 9270967055 Road (College Road) Shevgaon Behind Khedkar Hospital, Pathardi AHMEDNAGAR PATHARDI Dot com computers Kishor Karad 02428-221101 9850351356 Pincode 414102 Gayatri computer OPP.SBI ,PARNER-SUPA ROAD,AT/POST- 02488-221177 AHMEDNAGAR PARNER Indrajit Deshmukh 9404042045 institute PARNER,TAL-PARNER, DIST-AHMEDNAGR /221277/9922007702 Shop no.8, Orange corner, college road AHMEDNAGAR SANGAMNER Dhananjay computer Swapnil Waghchaure Sangamner, Dist- 02425-220704 9850528920 Ahmednagar. Pin- 422605 Near S.T. Stand,4,First Floor Nagarpalika Shopping Center,New Nagar Road, 02425-226981/82 AHMEDNAGAR SANGAMNER Shubham Computers Yogesh Bhagwat 9822069547 Sangamner, Tal. Sangamner, Dist /7588025925 Ahmednagar Opposite OLD Nagarpalika AHMEDNAGAR KOPARGAON Cybernet Systems Shrikant Joshi 02423-222366 / 223566 9763715766 Building,Kopargaon – 423601 Near Bus Stand, Behind Hotel Prashant, AHMEDNAGAR AKOLE Media Infotech Sudhir Fargade 02424-222200 7387112323 Akole, Tal Akole Dist Ahmadnagar K V Road ,Near Anupam photo studio W 02422-226933 / AHMEDNAGAR SHRIRAMPUR Manik Computers Sachin SONI 9763715750 NO 6 ,Shrirampur 9850031828 HI-TECH Computer -

LATUR ZONE, LATUR. Admin

MAHAVITARAN RTI ONLINE Maharashtra State Electricity Distribution Company Ltd. LATUR ZONE, LATUR. Admin. Bldg.,1 st. Floor, Old Power House, Sale Galli, Latur- 413 512. Name of Nodal Nodal Officer, Officer, Public Public Information Landli Sr. Information Officer / ne / Designatio E-mail Address given by NIC No Office Name Officer / First First Mobile n in office or IT . Appellate Appellate Numb Authority Authority er and System and System Administrato Administrat r or 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Chief PIO & Engineer Exe. M. S. Misal System Office, Engineer Administrato Admin. Bldg.,1 r Ph. st. Floor, Old 02382- 1 [email protected] Power House, 25334 FAA & Sale Galli, Chief R. B. Burud Nodal 4 Latur- 413 Engineer Officer 512. Ph. D. D. PIO & Suptdg. 02382- Hamand System [email protected] Engineer Administrato 25709 Infrastructure Plan, r 3 2 Latur Zone, Ph. Latur. Chief FAA & 02382- R. B. Burud Nodal [email protected] Engineer 25334 Officer 4 Latur Circle PIO & Shrikrishna Office, System Admin. Ramchandra Exe. Administrato Ph. Bldg.,Ground Kulkarni Engineer r 02382- 3 floor, Old [email protected] 24532 Power House, Sachin FAA & 9 Sale Galli, Laxmikant Suptdg. Nodal Latur- 413 Talewar Engineer Officer 512. Latur Rumdeo Poma PIO & Ph. Division Add. Exe. System 4 Chavan 02382- [email protected] Office, Engineer Administrato Old Power r 24416 1 House, Sale Madan 2 FAA & Galli, Latur- Kisanrao Exe. Nodal 413 512. Sangle Engineer Officer Ph. Mangalsing PIO & 02382 Bandu Add. Exe. System - [email protected] Latur North Chavhan Engineer Administrato Urban r 24421 5 Sub Division. 2 Sale Galli, Madan Ph. -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

0001S07 Prashant M.Nijasure F 3/302 Rutu Enclave,Opp.Muchal

Effective Membership ID Name Address Contact Numbers from Expiry F 3/302 Rutu MH- Prashant Enclave,Opp.Muchala 9320089329 12/8/2006 12/7/2007 0001S07 M.Nijasure Polytechnic, Ghodbunder Road, Thane (W) 400607 F 3/302 Rutu MH- Enclave,Opp.Muchala Jilpa P.Nijasure 98210 89329 8/12/2006 8/11/2007 0002S07 Polytechnic, Ghodbunder Road, Thane (W) 400607 MH- C-406, Everest Apts., Church Vianney Castelino 9821133029 8/1/2006 7/30/2011 0003C11 Road-Marol, Mumbai MH- 6, Nishant Apts., Nagraj Colony, Kiran Kulkarni +91-0233-2302125/2303460 8/2/2006 8/1/2007 0004S07 Vishrambag, Sangli, 416415 MH- Ravala P.O. Satnoor, Warud, Vasant Futane 07229 238171 / 072143 2871 7/15/2006 7/14/2007 0005S07 Amravati, 444907 MH MH- Jadhav Prakash Bhood B.O., Khanapur Taluk, 02347-249672 8/2/2006 8/1/2007 0006S07 Dhondiram Sangli District, 415309 MH- Rajaram Tukaram Vadiye Raibag B.O., Kadegaon 8/2/2006 8/1/2007 0007S07 Kumbhar Taluk, Sangli District, 415305 Hanamant Village, Vadiye Raibag MH- Popat Subhana B.O., Kadegaon Taluk, Sangli 8/2/2006 8/1/2007 0008S07 Mandale District, 415305 Hanumant Village, Vadiye Raibag MH- Sharad Raghunath B.O., Kadegaon Taluk, Sangli 8/2/2006 8/1/2007 0009S07 Pisal District, 415305 MH- Omkar Mukund Devrashtra S.O., Palus Taluk, 8/2/2006 8/1/2007 0010S07 Vartak Sangli District, 415303 MH MH- Suhas Prabhakar Audumbar B.O., Tasgaon Taluk, 02346-230908, 09960195262 12/11/2007 12/9/2008 0011S07 Patil Sangli District 416303 MH- Vinod Vidyadhar Devrashtra S.O., Palus Taluk, 8/2/2006 8/1/2007 0012S07 Gowande Sangli District, 415303 MH MH- Shishir Madhav Devrashtra S.O., Palus Taluk, 8/2/2006 8/1/2007 0013S07 Govande Sangli District, 415303 MH Patel Pad, Dahanu Road S.O., MH- Mohammed Shahid Dahanu Taluk, Thane District, 11/24/2005 11/23/2006 0014S07 401602 3/4, 1st floor, Sarda Circle, MH- Yash W. -

Section 124- Unpaid and Unclaimed Dividend

Sr No First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 ASHOK KUMAR GOLCHHA 305 ASHOKA CHAMBERS ADARSHNAGAR HYDERABAD 500063 0000000000B9A0011390 36.00 2 ADAMALI ABDULLABHOY 20, SUKEAS LANE, 3RD FLOOR, KOLKATA 700001 0000000000B9A0050954 150.00 3 AMAR MANOHAR MOTIWALA DR MOTIWALA'S CLINIC, SUNDARAM BUILDING VIKRAM SARABHAI MARG, OPP POLYTECHNIC AHMEDABAD 380015 0000000000B9A0102113 12.00 4 AMRATLAL BHAGWANDAS GANDHI 14 GULABPARK NEAR BASANT CINEMA CHEMBUR 400074 0000000000B9A0102806 30.00 5 ARVIND KUMAR DESAI H NO 2-1-563/2 NALLAKUNTA HYDERABAD 500044 0000000000B9A0106500 30.00 6 BIBISHAB S PATHAN 1005 DENA TOWER OPP ADUJAN PATIYA SURAT 395009 0000000000B9B0007570 144.00 7 BEENA DAVE 703 KRISHNA APT NEXT TO POISAR DEPOT OPP OUR LADY REMEDY SCHOOL S V ROAD, KANDIVILI (W) MUMBAI 400067 0000000000B9B0009430 30.00 8 BABULAL S LADHANI 9 ABDUL REHMAN STREET 3RD FLOOR ROOM NO 62 YUSUF BUILDING MUMBAI 400003 0000000000B9B0100587 30.00 9 BHAGWANDAS Z BAPHNA MAIN ROAD DAHANU DIST THANA W RLY MAHARASHTRA 401601 0000000000B9B0102431 48.00 10 BHARAT MOHANLAL VADALIA MAHADEVIA ROAD MANAVADAR GUJARAT 362630 0000000000B9B0103101 60.00 11 BHARATBHAI R PATEL 45 KRISHNA PARK SOC JASODA NAGAR RD NR GAUR NO KUVO PO GIDC VATVA AHMEDABAD 382445 0000000000B9B0103233 48.00 12 BHARATI PRAKASH HINDUJA 505 A NEEL KANTH 98 MARINE DRIVE P O BOX NO 2397 MUMBAI 400002 0000000000B9B0103411 60.00 13 BHASKAR SUBRAMANY FLAT NO 7 3RD FLOOR 41 SEA LAND CO OP HSG SOCIETY OPP HOTEL PRESIDENT CUFFE PARADE MUMBAI 400005 0000000000B9B0103985 96.00 14 BHASKER CHAMPAKLAL -

Integrated State Water Plan for Lower Bhima Sub Basin (K-6) of Krishna Basin

Maharashtra Krishna Valley Development Corporation Pune. Chief Engineer (S.P) W.R.D Pune. Integrated state water Plan for Lower Bhima Sub basin (K-6) of Krishna Basin Osmanabad Irrigation Circle, Osmanabad K6 Lower Bhima Index INDEX CHAPTER PAGE NO. NAME OF CHAPTER NO. 1.0 INTRODUCTION 0 1.1 Need and principles of integrated state water plan. 1 1.2 Objectives of a state water plan for a basin. 1 1.3 Objectives of the maharashtra state water policy. 1 1.4 State water plan. 1 1.5 Details of Catchment area of Krishna basin. 2 1.6 krishna basin in maharashtra 2 1.7 Location of lower Bhima sub basin (K-6). 2 1.8 Rainfall variation in lower Bhima sub basin. 2 1.9 Catchment area of sub basin. 3 1.10 District wise area of lower Bhima sub basin. 3 1.11 Topographical descriptions. 5 1.11 Flora and Fauna in the sub basin. 6 2.0 RIVER SYSTEM 2.1 Introduction 11 2.2 Status of Rivers & Tributaries. 11 2.3 Topographical Description. 11 2.4 Status of Prominent Features. 12 2.5 Geomorphology. 12 2.6 A flow chart showing the major tributaries in the sub basin. 13 3.0 GEOLOGY AND SOILS 3.1 Geology. 16 3.1.1 Introduction. 16 3.1.2 Drainage. 16 3.1.3 Geology. 16 3.1.4 Details of geological formation. 17 K6 Lower Bhima Index 3.2 Soils 18 3.2.1 Introduction. 18 3.2.2 Land capability Classification of Lower Bhima Sub Basin (K6). -

On the Importance of Triangulating Data Sets to Examine Indians on the Move

SPECIAL ARTICLE On the Importance of Triangulating Data Sets to Examine Indians on the Move S Chandrasekhar, Mukta Naik, Shamindra Nath Roy A chapter dedicated to migration in the Economic Survey t would not be an exaggeration to say that migration statis- 2016–17 signals the willingness on the part of Indian tics has not been anyone’s priority in India. The National Sample Survey Offi ce’s (NSSO) survey of employment– policymakers to address the linkages between I unemployment and migration was last conducted in 2007–08. migration, labour markets, and economic development. Subsequent surveys of NSSO, at best, have had a question or This paper attempts to take forward this discussion. We two on a specifi c aspect of migration, which are certainly not comment on the salient mobility trends in India gleaned enough to piece together any compelling evidence on migration fl ows. Based on information collected as part of the Census of from existing data sets, and then compare and critique India 2011, the Offi ce of the Registrar General and Census estimates of the Economic Survey with traditional data Commissioner, India (RGI) has released exactly one state- sets. After highlighting the data and resultant specifi c table on internal migration in India. The year is 2017 knowledge gaps, the article comments on the possibility and we know precious little about migration patterns between 2001 and 2011, leave alone what is happening in real time. As a of using innovative data sources and methods to result, in the era of “smart” and “digital,” programmes and understand migration and human mobility. -

By Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Vidyavachaspati (Doctor of Philosophy) Faculty for Moral and Social Sciences Department Of

“A STUDY OF AN ECOLOGICAL PATHOLOGICAL AND BIO-CHEMICAL IMPACT OF URBANISATION AND INDUSTRIALISATION ON WATER POLLUTION OF BHIMA RIVER AND ITS TRIBUTARIES PUNE DISTRICTS, MAHARASHTRA, INDIA” BY Dr. PRATAPRAO RAMGHANDRA DIGHAVKAR, I. P. S. THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF VIDYAVACHASPATI (DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY) FACULTY FOR MORAL AND SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY TILAK MAHARASHTRA VIDHYAPEETH PUNE JUNE 2016 CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the entire work embodied in this thesis entitled A STUDY OFECOLOGICAL PATHOLOGICAL AND BIOCHEMICAL IMPACT OF URBANISATION AND INDUSTRILISATION ON WATER POLLUTION OF BHIMA RIVER AND Its TRIBUTARIES .PUNE DISTRICT FOR A PERIOD 2013-2015 has been carried out by the candidate DR.PRATAPRAO RAMCHANDRA DIGHAVKAR. I. P. S. under my supervision/guidance in Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune. Such materials as has been obtained by other sources and has been duly acknowledged in the thesis have not been submitted to any degree or diploma of any University or Institution previously. Date: / / 2016 Place: Pune. Dr.Prataprao Ramchatra Dighavkar, I.P.S. DECLARATION I hereby declare that this dissertation entitled A STUDY OF AN ECOLOGICAL PATHOLOGICAL AND BIO-CHEMICAL IMPACT OF URBANISNTION AND INDUSTRIALISATION ON WATER POLLUTION OF BHIMA RIVER AND Its TRIBUTARIES ,PUNE DISTRICT FOR A PERIOD 2013—2015 is written and submitted by me at the Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The present research work is of original nature and the conclusions are base on the data collected by me. To the best of my knowledge this piece of work has not been submitted for the award of any degree or diploma in any University or Institution. -

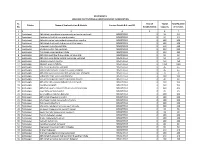

Sr. No. Taluka Name of the Institution & Hostels Contact Details & E- Mail

STATEMENT-I WELFARE INSTITUTIONS & HOSTELS SCHEME INFORMATION Sr. Yeat of Toatal Total Number Taluka Name of the Institution & Hostels Contact Details & E- mail ID No. Establishment Capacity of Inmates 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 Ambajogai Adhikshak vasundhara magaswargiy mulanche vastigrah 9850276553 0 24 24 2 Ambajogai Rastriya dalit shikshn prasarak mandal 9850276553 0 24 24 3 Ambajogai Adhyaksh vatan bahuuddeshiya sevabhavi sanstha 9850276553 0 100 100 4 Ambajogai Adhikshak chatrapati shahu maharaj bal sadan 9850276553 0 100 100 5 Ambajogai Yogeswari vidyarthi vastigrah 9850276553 0 110 110 6 Ambajogai Mhatma jyotiba fule vastigrah 9850276553 0 250 250 7 Ambajogai Tulsi kisan niwasi aashram shala 9850276553 0 150 150 8 Ambajogai Adhikshk sawitribai fule muliche nirikshn grah 9850276553 0 50 50 9 Ambajogai Adhikshk vasundahra balgrah mulanche vastigrah 9850276553 0 50 50 10 Ambajogai Bhumika viswast sanstha 9850276553 0 150 150 11 Ambajogai Adyaksh madrsa fallaha 9850276553 0 1000 1000 12 Ambajogai Maji sainik mulanche vastigrah 9850276553 0 45 45 13 Ambajogai Babasaheb paranjpe mulanche niwasi vastigrah 9850276553 0 45 45 14 Ambajogai Adhikshk swami ramanand tirth gramin pari. Vastigrah 9850276553 0 70 70 15 Ambajogai Sidhanath sama v seva sanstha latur 9850276553 0 100 100 16 Ambajogai Sa.sumatibai gunale shikshan prasarak mandal 9850276553 0 40 40 17 Ambajogai Adhikshk sidhi vinayak balkashram morewadi 9850276553 0 100 100 18 Ambajogai Kaushlya balagrah 9850276553 0 100 100 19 Ambajogai Adhkshak swami ramand tirth gra.vai.mahavidyalay 9850276553 -

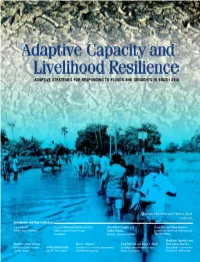

Marcus Moench and Ajaya Dixit ADAPTIVE STRATEGIES FOR

ADAPTIVE STRATEGIES FOR RESPONDING TO FLOODS AND DROUGHTS IN SOUTH ASIA Marcus Moench and Ajaya Dixit EDITORS Contributors and their Institutions Sara Ahmed Sanjay Chaturvedi and Eva Saroch Shashikant Chopde and Ajaya Dixit and Dipak Gyawali Independent Consultant Indian Ocean Research Group, Sudhir Sharma Institute for Social and Environmental Chandigarh Winrock International-India Transition-Nepal Madhukar Upadhya and Manohar Singh Rathore Marcus Moench Tariq Rehman and Shiraj A. Wajih Ram Kumar Sharma Institute of Development Srinivas Mudrakartha Institute for Social and Environmental Gorakhpur Environmental Action Nepal Water Conservation Studies, Jaipur VIKSAT, Ahmedabad Transition-International Group, Gorakhpur Foundation, Kathmandu ADAPTIVE STRATEGIES FOR RESPONDING TO FLOODS AND DROUGHTS IN SOUTH ASIA Marcus Moench and Ajaya Dixit EDITORS Contributors and their Institutions Sara Ahmed Sanjay Chaturvedi and Eva Saroch Shashikant Chopde and Ajaya Dixit and Dipak Gyawali Independent Consultant Indian Ocean Research Group, Sudhir Sharma Institute for Social and Environmental Chandigarh Winrock International-India Transition-Nepal Marcus Moench Madhukar Upadhya and Manohar Singh Rathore Institute for Social and Tariq Rehman and Shiraj A. Wajih Ram Kumar Sharma Institute of Development Srinivas Mudrakartha Environmental Transition- Gorakhpur Environmental Action Nepal Water Conservation Studies, Jaipur VIKSAT, Ahmedabad International Group, Gorakhpur Foundation, Kathmandu © Copyright, 2004 Institute for Social and Environmental Transition, International, Boulder Institute for Social and Environmental Transition, Nepal No part of this publication may be reproduced or copied in any form without written permission. This project was supported by the Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA) and the U.S. State Department through a co-operative agreement with the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). -

Chapm I INTRODUCTION I Geographical Aspects of Ichandesh

C H A P m I INTRODUCTION I Geographical aspects of IChandesh Khandesh, lying between 20* 8' and 22* 7* north latitude and 75* 42' and 76* 28' longitude with a total area of 20,099 sQuare Km formed the 'most northern district' of the terri tories under tne control of the sole Conunissioner of Deccan in 1818 Ad J Stretching nearly 256 Kin along the Tapi and varying in breadth from 92 to 144 iOn, Khaiidesh forms an upland basin, the most northerly section of the Deccan table-laiid. Captain John Briggs, the then Political Agent of Khandesh (1818-1823) described Khandesh as 'bounded on the south by the range of Hills in v/hich the forts of Kunhur, Uhkye and Chandoor lie; on tue north by the Satpoora Mountains; on the east by the districts of Aseer, Zeinabad, Edlabad, Badur, sind Jamner, 2 and on the west by the Hills and forests of Baglana', Prom the north-east corner, as far as the Sindwa pass on the Agra roaa, the hiil coimtry belonged to Holkar, Purther »i/est, in Sahada, the Khandesh bounaary skirts, the base of the hills; then, including the Akrani territory, it moved north, right into the heart of the hills, to where, in a deep narrow channel, the Narmada forces its way through the Satpuda. Prom this to its north-west centre, the Narmada remained the northern boundary of the district* On the east ana south-east, a row of pillars and some conveiiient streams without any marked natiiral boimdary, separated Khandesh 1‘rom the central Provinces and Berar, To the south of the Ajanta, Satmala or Chandor marked the line between Khandesh and the Mizam’s territory.