3 4 0 ^ 1 0 ^ Folklore Contributions in Sino-Mongoliga

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Auction Will Take Place at 9 A.M. (+8 G.M.T.) Sunday 18Th October 2020 at 2/135 Russell St, Morley, Western Australia

The Auction will take place at 9 a.m. (+8 G.M.T.) Sunday 18th October 2020 at 2/135 Russell St, Morley, Western Australia. Viewing of lots will take place on Saturday 17th October 9am to 4pm & Sunday 18th October 7:00am to 8:45am, with the auction taking place at 9am and finishing around 5:00pm. Photos of each lot can be viewed via our ‘Auction’ tab of our website www.jbmilitaryantiques.com.au Onsite registration can take place before & during the auction. Bids will only be accepted from registered bidders. All telephone and absentee bids need to be received 3 days prior to the auction. Online registration is via www.invaluable.com. All prices are listed in Australian Dollars. The buyer’s premium onsite, telephone & absentee bidding is 18%, with internet bidding at 23%. All lots are guaranteed authentic and come with a 90-day inspection/return period. All lots are deemed ‘inspected’ for any faults or defects based on the full description and photographs provided both electronically and via the pre-sale viewing, with lots sold without warranty in this regard. We are proud to announce the full catalogue, with photographs now available for viewing and pre-auction bidding on invaluable.com (can be viewed through our website auction section), as well as offering traditional floor, absentee & phone bidding. Bidders agree to all the ‘Conditions of Sale’ contained at the back of this catalogue when registering to bid. Post Auction Items can be collected during the auction from the registration desk, with full payment and collection within 7 days of the end of the auction. -

E6 D20 Stalker Zone Stalker

E6 D20 Stalker Zone Stalker. Enjoy your stay. Welcome to the D20 Stalker Game supplement for the D20 Modern system. The Zone: was relatively peaceful until sometime Before the 1986 disaster, the remote areas around 2001, when a bus full of tourists in around Chernobyl and Pripyat were used the zone disappeared. The incident by the Soviet Union for research and prompted the government to fully restrict development of psychotropic weapons the zone to civilians. In 2011, stalkers and study of the noospher[1] One of the reported encountering zombies who spoke earliest such programs was undertaken at garbled English, revealing the fate of the Limansk-13, a secret city where top Soviet tourists. scientists experimented with radiowaves, The first experiment in affecting human in order to harness them as a tool, to psyche on a massive scale took place on create unflinching loyalty to the Union in March 4, 2006[3]. It lasted two full hours all affected people. before it was shut down, likely due to However, the research was not safe. A unforeseen developments. A month later, surge in energy consumption during one on April 12, the experiment was performed of the experiments on April 26, 1986 was again and this time it continued until its one of the main reasons Reactor 4 completion[4]. However, it did not have the exploded. In response to the incident, the desired effect - instead, the generators USSR evacuated Pripyat and settlements in created a rift in the noosphere, allowing it the neighboring areas, until the Zone to directly affect the biosphere, creating a became almost totally deserted, save for a large area where physical laws were few die hard citizens (including the outright broken and mysterious Forester) and scientific teams working in phenomena not understood by modern secret laboratories. -

Consejo De Seguridad Distr

Naciones Unidas S/2018/1002 Consejo de Seguridad Distr. general 9 de noviembre de 2018 Español Original: inglés Carta de fecha 7 de noviembre de 2018 dirigida al Presidente del Consejo de Seguridad por el Presidente del Comité del Consejo de Seguridad dimanante de las resoluciones 751 (1992) y 1907 (2009) relativas a Somalia y Eritrea En nombre del Comité del Consejo de Seguridad dimanante de las resoluciones 751 (1992) y 1907 (2009) relativas a Somalia y Eritrea, y de conformidad con el párrafo 48 de la resolución 2385 (2017) del Consejo de Seguridad, tengo el honor de transmitir adjunto el informe sobre Somalia del Grupo de Supervisión para Somalia y Eritrea. A ese respecto, el Comité agradecería que la presente carta y el informe se señalaran a la atención de los miembros del Consejo de Seguridad y se publicaran como documento del Consejo. (Firmado) Kairat Umarov Presidente Comité del Consejo de Seguridad dimanante de las resoluciones 751 (1992) y 1907 (2009) relativas a Somalia y Eritrea 18-16126 (S) 091118 131118 *1816126* S/2018/1002 Carta de fecha 2 de octubre de 2018 dirigida al Presidente del Comité del Consejo de Seguridad dimanante de las resoluciones 751 (1992) y 1907 (2009) relativas a Somalia y Eritrea por el Grupo de Supervisión para Somalia y Eritrea De conformidad con el párrafo 48 de la resolución 2385 (2017) del Consejo de Seguridad, tenemos el honor de transmitir adjunto el informe sobre Somalia del Grupo de Supervisión para Somalia y Eritrea. (Firmado) James Smith Coordinador Grupo de Supervisión para Somalia y Eritrea (Firmado) Jay Bahadur Experto en grupos armados (Firmado) Charles Cater Experto en recursos naturales (Firmado) Mohamed Abdelsalam Babiker Experto en asuntos humanitarios (Firmado) Brian O’Sullivan Experto en grupos armados/cuestiones marítimas (Firmado) Nazanine Moshiri Experta en armas (Firmado) Richard Zabot Experto en armas 2/160 18-16126 S/2018/1002 Resumen En 1992 se impuso a Somalia un embargo de armas general y completo en virtud de la resolución 733 (1992) del Consejo de Seguridad. -

AWE and BEAUTY Joint Proof and Experimental Unit – a History Doctor Steven Anthony Schmied

AWE AND BEAUTY Joint Proof And Experimental Unit – A History Doctor Steven Anthony Schmied AWE AND BEAUTY A History of the Joint Proof and Experimental Unit Doctor Steven Anthony Schmied © Commonwealth Of Australia 2019 First Published 2019 This work is copyright. Permission is given by the Commonwealth of Australia for this publication to be copied royalty free within Australia solely for educational purposes. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced for commercial purposes. Designed and produced by Big Sky Publishing www.bigskypublishing.com.au AWE AND BEAUTY A History of the Joint Proof and Experimental Unit Doctor Steven Anthony Schmied www.bigskypublishing.com.au CONTENTS Chapter 1. Awe And Beauty ..........................................................................................................................................04 Chapter 2. Graytown ....................................................................................................................................................12 Chapter 3. Port Wakefield .............................................................................................................................................46 Chapter 4. Orchard Hills ..............................................................................................................................................73 Chapter 5. The Work ....................................................................................................................................................75 -

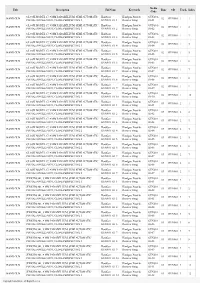

Title Description Filename Keywords Media Code Time CD Track Index

Media Title Description FileName Keywords Time CD Track Index Code GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC HandGun Handgun, Pistol & GUNS01- HAND GUN :02 GUNS01 1 1 PISTOL: SINGLE SHOT, CLOSE PERSPECTIVE 1 GUNS01_01_1 Revolver Firing 01-01 GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC HandGun Handgun, Pistol & GUNS01- HAND GUN :02 GUNS01 1 2 PISTOL: SINGLE SHOT, CLOSE PERSPECTIVE 1 GUNS01_01_2 Revolver Firing 01-02 GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC HandGun Handgun, Pistol & GUNS01- HAND GUN :02 GUNS01 1 3 PISTOL: SINGLE SHOT, CLOSE PERSPECTIVE 1 GUNS01_01_3 Revolver Firing 01-03 GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC HandGun Handgun, Pistol & GUNS01- HAND GUN :02 GUNS01 1 4 PISTOL: SINGLE SHOT, CLOSE PERSPECTIVE 1 GUNS01_01_4 Revolver Firing 01-04 GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC HandGun Handgun, Pistol & GUNS01- HAND GUN :02 GUNS01 1 5 PISTOL: SINGLE SHOT, CLOSE PERSPECTIVE 1 GUNS01_01_5 Revolver Firing 01-05 GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC HandGun Handgun, Pistol & GUNS01- HAND GUN :02 GUNS01 1 6 PISTOL: SINGLE SHOT, CLOSE PERSPECTIVE 1 GUNS01_01_6 Revolver Firing 01-06 GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC HandGun Handgun, Pistol & GUNS01- HAND GUN :02 GUNS01 1 7 PISTOL: SINGLE SHOT, CLOSE PERSPECTIVE 1 GUNS01_01_7 Revolver Firing 01-07 GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC HandGun Handgun, Pistol & GUNS01- HAND GUN :02 GUNS01 1 8 PISTOL: SINGLE SHOT, CLOSE PERSPECTIVE 1 GUNS01_01_8 Revolver Firing 01-08 GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC -

6 North and South Ossetia: Old Conflicts and New Fears

6 North and South Ossetia: Old conflicts and new fears Alan Parastaev Erman village in the high Caucasus mountains of South Ossetia PHOTO: PETER NASMYTH Summary The main source of weapons in South Ossetia during the conflict with Georgian forces in the early 1990s was Chechnya, but towards the end of the conflict arms were also obtained from Russian troops in North Ossetia. Following the end of the conflict in 1992, the unrecognised Republic of South Ossetia began to construct its own security structures. The government has made some attempts to control SALW proliferation and collect weapons from the population, as has the OSCE, though these programmes have had limited success. In North Ossetia it was much easier to acquire weapons from Russian military sources than in the South. North Ossetia fought a short war against the Ingush in 1992, and though relations between the two are now stable, North Ossetia is still very sensitive to events elsewhere in the North Caucasus. Recently, however, the increase in Russian military activity in the region has acted as a stabilising factor. Unofficial estimates of the amount of SALW in North Ossetia range between 20,000 and 50,000. 2 THE CAUCASUS: ARMED AND DIVIDED · NORTH AND SOUTH OSSETIA The years of The events at the end of the 1980s ushered in by perestroika – the move by the leader- conflict ship of the CPSU towards the democratisation of society – had an immediate impact on the social and political situation in South Ossetia and Georgia as a whole. In both Tbilisi and the South Ossetian capital Tskhinval national movements sprang to life which would in time evolve into political parties and associations. -

JSS 063 2B Workshoponsouth

PAPERS PRESENTED AT THE WORKSHOP ON SOUTHEAST' ASIAN LANGUAGES THEME:' LINGUISTIC PROBLEMS IN MINORITY /MAJORITY GROUP RELATIONS IN SOUTHEAST ASIAN COUNTRIES MAHIDOL UNIVERSITY, BANGKOK, 13-17 JANUARY 1975. * * * WHY AND HOW THE "SMALL LANGUAGES" SHOULD BE STUDIED by A.G. Haudricourt* The languages which gene;rally form the object of teaching and study are those spoken by a number of people and endowed with a prolific literature. On the other hand, a question may be raised: why should languages spoken by few people and are never written be studied? There are at least three reasons: 1. Anthropological reason. If one'wishes to know a people scienti fically it is necessary to study its language and oral literature for the fact that a language is never written does not mean that it has neither grammar, nor poetry, nor folktales. · 2. Educational reason. If one wishes a minority population to participate in the national life, itis essential that there be schools where the national language is taught. Now,; all educationists know that it is in the first place necessary for children to learn to write in their mother tongue before proceeding to learn the national language wit.h complete success. * Prof~$seur, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Pari$, 2 A.G. Haudricourt 3. Historical reason. Peoples without writing are not without history but this history is not clearly formulated; it is simply woven into the language and thanks to the comparative linguistic methods we are able to establish the various relationships of the language under the question with the other languages of the region. -

Sound Ideas Guns Sound Effects Series Complete Track and Index

Sound Ideas Guns Sound Effects Series Complete Track and Index Listing CD # Tr/In Title & Description Time GUNS01 01-01 HAND GUN GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC PISTOL: SINGLE SHOT, CLOSE PERSPECTIVE 1 :02 GUNS01 01-02 HAND GUN GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC PISTOL: SINGLE SHOT, CLOSE PERSPECTIVE 1 :02 GUNS01 01-03 HAND GUN GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC PISTOL: SINGLE SHOT, CLOSE PERSPECTIVE 1 :02 GUNS01 01-04 HAND GUN GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC PISTOL: SINGLE SHOT, CLOSE PERSPECTIVE 1 :02 GUNS01 01-05 HAND GUN GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC PISTOL: SINGLE SHOT, CLOSE PERSPECTIVE 1 :02 GUNS01 01-06 HAND GUN GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC PISTOL: SINGLE SHOT, CLOSE PERSPECTIVE 1 :02 GUNS01 01-07 HAND GUN GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC PISTOL: SINGLE SHOT, CLOSE PERSPECTIVE 1 :02 GUNS01 01-08 HAND GUN GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC PISTOL: SINGLE SHOT, CLOSE PERSPECTIVE 1 :02 GUNS01 01-09 HAND GUN GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC PISTOL: SINGLE SHOT, CLOSE PERSPECTIVE 1 :02 GUNS01 01-10 HAND GUN GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC PISTOL: SINGLE SHOT, CLOSE PERSPECTIVE 1 :02 GUNS01 02-01 HAND GUN GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC PISTOL: SINGLE SHOT, CLOSE PERSPECTIVE 2 :03 GUNS01 02-02 HAND GUN GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC PISTOL: SINGLE SHOT, CLOSE PERSPECTIVE 2 :03 GUNS01 02-03 HAND GUN GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC PISTOL: -

Inventory to Archival Boxes in the Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress

INVENTORY TO ARCHIVAL BOXES IN THE MOTION PICTURE, BROADCASTING, AND RECORDED SOUND DIVISION OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Compiled by MBRS Staff (Last Update December 2017) Introduction The following is an inventory of film and television related paper and manuscript materials held by the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress. Our collection of paper materials includes continuities, scripts, tie-in-books, scrapbooks, press releases, newsreel summaries, publicity notebooks, press books, lobby cards, theater programs, production notes, and much more. These items have been acquired through copyright deposit, purchased, or gifted to the division. How to Use this Inventory The inventory is organized by box number with each letter representing a specific box type. The majority of the boxes listed include content information. Please note that over the years, the content of the boxes has been described in different ways and are not consistent. The “card” column used to refer to a set of card catalogs that documented our holdings of particular paper materials: press book, posters, continuity, reviews, and other. The majority of this information has been entered into our Merged Audiovisual Information System (MAVIS) database. Boxes indicating “MAVIS” in the last column have catalog records within the new database. To locate material, use the CTRL-F function to search the document by keyword, title, or format. Paper and manuscript materials are also listed in the MAVIS database. This database is only accessible on-site in the Moving Image Research Center. If you are unable to locate a specific item in this inventory, please contact the reading room. -

Army Special Forces Legend

Military Despatches Vol 45 March 2021 Thanks, but no thanks 10 dangerous roles in the military It pays to be a winner The US Navy SEALs An offer you can’t refuse Did the US Military and the Mafia collaborate? Colonel Arthur ‘Bull’ Simons US Army Special Forces legend For the military enthusiast CONTENTS March 2021 Page 14 Click on any video below to view How much do you know about movie theme songs? Take our quiz and find out. Hipe’s Wouter de The old South African Goede interviews former Defence Force used 28’s gang boss David a mixture of English, Williams. Afrikaans, slang and techno-speak that few Special Forces - US Navy SEALS outside the military could hope to under- 46 stand. Some of the terms Features Changes to the engine room were humorous, some 6 were clever, while others The Sea Cadets announce new were downright crude. Ten dangerous military roles appointments. These are ten military roles in 48 history that you did not want. Remembrance Day Part of Hipe’s “On the 22 32 Seaman Piper Pauwels from couch” series, this is an Who’s running the show? It’s not really a game TS Rook researches the mean- interview with one of The nine people that became How simulators are changing ing of Remembrance Day. author Herman Charles Chief of the SADF. the way the military trains. 50 Bosman’s most famous 24 36 characters, Oom Schalk Memories of a Sea Cadet An offer you can’t refuse Long distance air mail Deene Collopy, Country Man- A taxi driver was shot Lourens. -

On Yuan Chwang's Travels in India, 629-645 A.D

-tl Strata, Sfew Qotlt BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE WASON ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF CHARLES W. WASON CORNELL 76 1918 ^He due fnterllbrary Io^jj KlYSILL The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924071132769 ORIENTAL TRANSLATION FUND NEW SEFtlES. VOL. XIV. 0^ YUAN CHWAIG'S TRAVELS IN INDIA 629—645 A, D. THOMAS WATTERS M.R.A.S. EDITED, APTER HIS DEATH, T. W. RHYS DAVIDS, F.B.A. S. W. BUSHELL, M.D.; C.M.G. ->is<- LONDON ROYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY 22 ALBXMASLE STBBET 1904 w,\^q4(^ Ketrinttd by the Radar Promt hy C. G. RSder Ltd., LeipBig, /g2J. CONTENTS. PEEFACE V THOMAS WAITERS Vm TBANSIilTEEATION OF THE PlLGEEVl's NAME XI CHAP. 1. TITLE AND TEXT 1 2. THE INTBODUCTION 22 3. FEOM KAO CHANG TO THE THOUSAMD 8PEINGS . 44 4. TA&AS TO KAPIS ..." 82 5. GENERAL DESCRIPTION OP INDIA 131 6. LAMPA TO GANDHARA 180 7. UDTANA TO TrASTTMTR. 225 8. K4.SHMIB TO RAJAPUE 258 9. CHEH-KA TO MATHUEA 286 10. STHANESVAEA TO KAMTHA 316 11. KANTAKUBJA TO VI^OKA 340 12. SEAVASTI TO KUSINAEA 377 PREFACE. As will be seen from Dr. Bushell's obituary notice of Thomas "Watters, republished from the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society for 1901 at the end of those few words of preface, Mr, Watters left behind him a work, ready for the press, on the travels of Ylian-Chwang in India in the 7*'' Century a. -

The Accordion in the 19Th Century, Which We Are Now Presenting, Gorka Hermosa Focuses on 19Th C

ISBN 978-84-940481-7-3. Legal deposit: SA-104-2013. Cover design: Ane Hermosa. Photograph on cover by Lituanian “Man_kukuku”, bought at www.shutterstock.com. Translation: Javier Matías, with the collaboration of Jason Ferguson. 3 INDEX FOREWORD: by the Dr. Pr. Helmut Jacobs................................................................ 5 INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................... 7 CHAPTER I: Predecessors of the accordion.............................................................. 9 I.1- Appearance of the free reed instruments in Southeast Asia.................... 10 I.2- History of the keyboard aerophone instruments: The organ................... 13 I.3- First references to the free reed in Europe.............................................. 15 I.4- The European free reed: Christian Gottlieb Kratzenstein....................... 17 I.5- The modern free reed instrument family................................................ 18 CHAPTER II: Organologic history of the accordion............................................... 21 II.1- Invention of the accordion..................................................................... 21 II.1.1- Demian’s accordion..................................................................... 21 II.1.2- Comments on the invention of the accordion. ............................ 22 II.2- Organologic evolution of the accordion................................................ 24 II.3- Accordion Manufacturers.....................................................................