On Yuan Chwang's Travels in India, 629-645 A.D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Problems of Chronology in Gandhāran Art

Rienjang and Stewart (eds) Problems of Chronology in Gandhāran Art Edited by Wannaporn Rienjang Peter Stewart Problems of Chronology in Gandhāran Art Since the beginning of Gandhāran studies in the nineteenth century, chronology has been one of the most significant challenges to the understanding of Gandhāran art. Many other ancient societies, including those of Greece and Rome, have left a wealth of textual sources which have put their fundamental chronological frameworks beyond doubt. In the absence of such sources on a similar scale, even the historical eras cited on inscribed Gandhāran works of art have been hard to place. Few sculptures have such inscriptions and the majority lack any record of find-spot or even general provenance. Those known to have been found at particular sites were sometimes moved and reused in antiquity. Consequently, the provisional dates assigned to extant Gandhāran sculptures have sometimes differed by centuries, while the narrative of artistic development remains doubtful and inconsistent. Building upon the most recent, cross-disciplinary research, debate and excavation, this volume reinforces a new consensus about the chronology of Gandhāra, bringing the history of Gandhāran art into sharper focus than ever. By considering this tradition in its wider context, alongside contemporary Indian art and subsequent developments in Central Asia, the authors also open up fresh questions and problems which a new phase of research will need to address. Problems of Chronology in Gandhāran Art is the first publication of the Gandhāra Connections project at the University of Oxford’s Classical Art Research Centre, which has been supported by the Bagri Foundation and the Neil Kreitman Foundation. -

The Mahabharata

^«/4 •m ^1 m^m^ The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924071123131 ) THE MAHABHARATA OF KlUSHNA-DWAIPAYANA VTASA TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH PROSE. Published and distributed, chiefly gratis, BY PROTSP CHANDRA EOY. BHISHMA PARVA. CALCUTTA i BHiRATA PRESS. No, 1, Raja Gooroo Dass' Stbeet, Beadon Square, 1887. ( The righi of trmsMm is resem^. NOTICE. Having completed the Udyoga Parva I enter the Bhishma. The preparations being completed, the battle must begin. But how dan- gerous is the prospect ahead ? How many of those that were counted on the eve of the terrible conflict lived to see the overthrow of the great Knru captain ? To a KsJtatriya warrior, however, the fiercest in- cidents of battle, instead of being appalling, served only as tests of bravery that opened Heaven's gates to him. It was this belief that supported the most insignificant of combatants fighting on foot when they rushed against Bhishma, presenting their breasts to the celestial weapons shot by him, like insects rushing on a blazing fire. I am not a Kshatriya. The prespect of battle, therefore, cannot be unappalling or welcome to me. On the other hand, I frankly own that it is appall- ing. If I receive support, that support may encourage me. I am no Garuda that I would spurn the strength of number* when battling against difficulties. I am no Arjuna conscious of superhuman energy and aided by Kecava himself so that I may eHcounter any odds. -

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

Mahayana Buddhism: the Doctrinal Foundations, Second Edition

9780203428474_4_001.qxd 16/6/08 11:55 AM Page 1 1 Introduction Buddhism: doctrinal diversity and (relative) moral unity There is a Tibetan saying that just as every valley has its own language so every teacher has his own doctrine. This is an exaggeration on both counts, but it does indicate the diversity to be found within Buddhism and the important role of a teacher in mediating a received tradition and adapting it to the needs, the personal transformation, of the pupil. This divers- ity prevents, or strongly hinders, generalization about Buddhism as a whole. Nevertheless it is a diversity which Mahayana Buddhists have rather gloried in, seen not as a scandal but as something to be proud of, indicating a richness and multifaceted ability to aid the spiritual quest of all sentient, and not just human, beings. It is important to emphasize this lack of unanimity at the outset. We are dealing with a religion with some 2,500 years of doctrinal development in an environment where scho- lastic precision and subtlety was at a premium. There are no Buddhist popes, no creeds, and, although there were councils in the early years, no attempts to impose uniformity of doctrine over the entire monastic, let alone lay, establishment. Buddhism spread widely across Central, South, South-East, and East Asia. It played an important role in aiding the cultural and spiritual development of nomads and tribesmen, but it also encountered peoples already very culturally and spiritually developed, most notably those of China, where it interacted with the indigenous civilization, modifying its doctrine and behaviour in the process. -

Logistics Capacity Assessment Nepal

IA LCA – Nepal 2009 Version 1.05 Logistics Capacity Assessment Nepal Country Name Nepal Official Name Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal Regional Bureau Bangkok, Thailand Assessment Assessment Date: From 16 October 2009 To: 6 November 2009 Name of the assessors Rich Moseanko – World Vision International John Jung – World Vision International Rajendra Kumar Lal – World Food Programme, Nepal Country Office Title/position Email contact At HQ: [email protected] 1/105 IA LCA – Nepal 2009 Version 1.05 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Country Profile....................................................................................................................................................................3 1.1. Introduction / Background.........................................................................................................................................5 1.2. Humanitarian Background ........................................................................................................................................6 1.3. National Regulatory Departments/Bureau and Quality Control/Relevant Laboratories ......................................16 1.4. Customs Information...............................................................................................................................................18 2. Logistics Infrastructure .....................................................................................................................................................33 2.1. Port Assessment .....................................................................................................................................................33 -

Palladas and the Age of Constantine Author(S): KEVIN W

Palladas and the Age of Constantine Author(s): KEVIN W. WILKINSON Source: The Journal of Roman Studies , 2009, Vol. 99 (2009), pp. 36-60 Published by: Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies constantinethegreatcoins.com Palladas and the Age of Constantine* KEVIN W. WILKINSON The poet and grammarian Palladas of Alexandria, author of more than 150 epigrams in the Greek Anthology, has remained a somewhat elusive figure. Though no epigrammatist is better represented in our two major sources for the Anthology, scarcely a trace of his exist- ence survives outside of his corpus of poems. His identity was so shadowy in the Byzantine period that he did not even warrant a mention in the Suda. By the tenth century, therefore, and presumably long before that time, 'Palladas' was merely the name of a man who had written some decent epigrams. Several clues remain, however, that allow us to locate him in a particular historical context. The history of scholarship on this problem is long and complex, but two rough timelines for his life have been proposed. The traditional estimate of his dates was c. A.D. 360-450. This was revised in the middle of the twentieth century to c. A.D. 319-400. It is my contention that the first of these is about a century too late and the second approximately sixty years too late. Such challenges to long-held opinion do not always enjoy a happy fate. Nevertheless, there are those cases in which the weight of scholarly tradition rests on surprisingly shaky foundations and in which a careful review of the evidence can result in significant improvements.1 The following argument proceeds in six stages: summary of the foundations for the traditional dates (1) and the current consensus (11); discussion of two external clues (in); challenge to the prevailing views (iv); construction of a new timeline (v); conclusions (vi). -

The Synagogue of Satan

THE SYNAGOGUE OF SATAN BY MAXIMILIAN J. RUDWIN THE Synagogue of Satan is of greater antiquity and potency than the Church of God. The fear of a mahgn being was earher in operation and more powerful in its appeal among primitive peoples than the love of a benign being. Fear, it should be re- membered, was the first incentive of religious worship. Propitiation of harmful powers was the first phase of all sacrificial rites. This is perhaps the meaning of the old Gnostic tradition that when Solomon was summoned from his tomb and asked, "Who first named the name of God?" he answered, "The Devil." Furthermore, every religion that preceded Christianity was a form of devil-worship in the eyes of the new faith. The early Christians actually believed that all pagans were devil-worshippers inasmuch as all pagan gods were in Christian eyes disguised demons who caused themselves to be adored under different names in dif- ferent countries. It was believed that the spirits of hell took the form of idols, working through them, as St. Thomas Aquinas said, certain marvels w'hich excited the wonder and admiration of their worshippers (Siiinina theologica n.ii.94). This viewpoint was not confined to the Christians. It has ever been a custom among men to send to the Devil all who do not belong to their own particular caste, class or cult. Each nation or religion has always claimed the Deity for itself and assigned the Devil to other nations and religions. Zoroaster described alien M^orshippers as children of the Divas, which, in biblical parlance, is equivalent to sons of Belial. -

Compassion & Social Justice

COMPASSION & SOCIAL JUSTICE Edited by Karma Lekshe Tsomo PUBLISHED BY Sakyadhita Yogyakarta, Indonesia © Copyright 2015 Karma Lekshe Tsomo No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the editor. CONTENTS PREFACE ix BUDDHIST WOMEN OF INDONESIA The New Space for Peranakan Chinese Woman in Late Colonial Indonesia: Tjoa Hin Hoaij in the Historiography of Buddhism 1 Yulianti Bhikkhuni Jinakumari and the Early Indonesian Buddhist Nuns 7 Medya Silvita Ibu Parvati: An Indonesian Buddhist Pioneer 13 Heru Suherman Lim Indonesian Women’s Roles in Buddhist Education 17 Bhiksuni Zong Kai Indonesian Women and Buddhist Social Service 22 Dian Pratiwi COMPASSION & INNER TRANSFORMATION The Rearranged Roles of Buddhist Nuns in the Modern Korean Sangha: A Case Study 2 of Practicing Compassion 25 Hyo Seok Sunim Vipassana and Pain: A Case Study of Taiwanese Female Buddhists Who Practice Vipassana 29 Shiou-Ding Shi Buddhist and Living with HIV: Two Life Stories from Taiwan 34 Wei-yi Cheng Teaching Dharma in Prison 43 Robina Courtin iii INDONESIAN BUDDHIST WOMEN IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE Light of the Kilis: Our Javanese Bhikkhuni Foremothers 47 Bhikkhuni Tathaaloka Buddhist Women of Indonesia: Diversity and Social Justice 57 Karma Lekshe Tsomo Establishing the Bhikkhuni Sangha in Indonesia: Obstacles and -

The Rattas Patronage to Jainism

Aayushi International Interdisciplinary Research Journal (AIIRJ) UGC Approved Sr.No.64259 Vol - V Issue-I JANUARY 2018 ISSN 2349-638x Impact Factor 4.574 The Rattas Patronage to Jainism Dr.S.G. Chalawadi Asst. Professor, Dept of A I History and Epigraphy Karnatak University, Dharwad The Rattas were the significant ruling dynasty, who claimed descent from the Rastrakutas. The earliest record is dated 980 A.D. It comes from the place called sogal. It is believed that sogal was their early capital, from where they shifted first to Soundatti and later on to Belgaum. Their reign continued till 1238 A.D.1 When they were thrown out of power by the seunas of Devagiri. The Rattas served under the Chalukyas of Kalyan and tried to become independent. When the Kalachuries displaced 'the Chalukyas generally the Rattas claimed authority over a large administrative division known as Kohundi or kondi 3000. This included major parts of Soundatti, Gokak, Hukkeri, Raibag, Chikkodi, Bailhongal and Mudhol, Jamakhandi talukas which fall in Belgaum and Bijapur districts. The line of descent of Rattas rulers, commences with Nanna and ends with Lakshmideva - II. In between there were eleven rulers, namely Karthavirya-I, Nanna - I, Erga, Anka, Nanna-II, Karthavirya II, Sena-II, Karthavirya-III, Lakshmideva-I, Karthavirya-IV and Mallikarjuna- II. The Rattas in the course of their rule patronaged both saivism and Jainism. By erecting temples and Basadis and giving much grants to them. One of the earliest references to Jaina patronage under the Rattas is noticed in Soundatti inscription. We are told that Karthavirya-I gave land (grants) to the Basadis constructed by Pritvirama his successors Kannakaira also gave grants to Jinalya at Soundatti. -

Life of Mahavira As Described in the Jai N a Gran Thas Is Imbu Ed with Myths Which

T o be h a d of 1 T HE MA A ( ) N GER , T HE mu Gu ms J , A llahaba d . Lives of greatmen all remin d u s We can m our v s su m ake li e bli e , A nd n v hi n u s , departi g , lea e be d n n m Footpri ts o the sands of ti e . NGF LL W LO E O . mm zm fitm m m ! W ‘ i fi ’ mz m n C NT E O NT S. P re face Introd uction ntrod uctor remar s and th i I y k , e h storicity of M ahavira Sources of information mt o o ica stories , y h l g l — — Family relations birth — — C hild hood e d ucation marriage and posterity — — Re nou ncing the world Distribution of wealth Sanyas — — ce re mony Ke sh alochana Re solution Seve re pen ance for twe lve years His trave ls an d pre achings for thirty ye ars Attai n me nt of Nirvan a His disciples and early followers — H is ch aracte r teachings Approximate d ate of His Nirvana Appendix A PREF CE . r HE primary con dition for th e formation of a ” Nation is Pride in a common Past . Dr . Arn old h as rightly asked How can th e presen t fru th e u u h v ms h yield it , or f t re a e pro i e , except t eir ” roots be fixed in th e past ? Smiles lays mu ch ’ s ss on h s n wh n h e s s in his h a tre t i poi t , e ay C racter, “ a ns l n v u ls v s n h an d N tio , ike i di id a , deri e tre gt su pport from the feelin g th at they belon g to an u s u s h h th e h s of h ill trio race , t at t ey are eir t eir n ss an d u h u s of h great e , o g t to be perpet ator t eir is of mm n u s im an h n glory . -

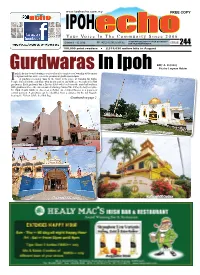

Your Voice in the Community Since 2006

www.ipohecho.com.my FREE COPY IPOH Your Voiceechoecho In The Community Since 2006 October 1 - 15, 2016 PP 14252/10/2012(031136) 30 SEN FOR DELIVERY TO YOUR DOORSTEP – ISSUE ASK YOUR NEWSVENDOR 244 100,000 print readers 2,315,636 online hits in August By A. Jeyaraj Pics by Luqman Hakim Gurdwaraspoh Echo has been featuring a series of articles on places of worship of the major In Ipoh religions and this issue covers the prominent gurdwaras in Ipoh. I A gurdwara meaning 'door to the Guru' is the place of worship for Sikhs. People from all faiths, and those who do not profess any faith, are welcomed in Sikh gurdwaras. Each gurdwara has a Darbar Sahib which refers to the main hall within a Sikh gurdwara where the current and everlasting Guru of the Sikhs, the holy scripture Sri Guru Granth Sahib, is placed on a Takhat (an elevated throne) in a prominent central position. A gurdwara can be identified from a distance by the tall flagpole bearing the Nishan Sahib, the Sikh flag. Continued on page 2 Gurdwara Sahib Greentown Central Sikh Temple Gurdwara Sahib Bercham Gurdwara Sahib Buntong 2 October 1 - 15, 2016 IPOH ECHO Your Voice In The Community Gurdwaras: a focal point for all Sikh religious, cultural and community activities erak, where most of the early Sikhs settled, and wherever there were Sikhs, a gurdwara was sure to follow, has the most number of gurdwaras with 42 out of a Gurdwara Sahib Greentown, Jalan Hospital Ptotal of 119 in Malaysia. The Gurdwara Sahib Greentown is situated on a hilltop and commands a majestic view of the surroundings. -

Witch Hunting

LE TAROT- ISTITUTO GRAF p resen t WITCH HUNTING C U R A T O R S FRANCO CARDINI - ANDREA VITALI GUGLIELMO INVERNIZZI - GIORDANO BERTI 1 HISTORICAL PRESENTATION “The sleep of reason produces monsters" this is the title of a work of the great Spanish painter Francisco Goya. He portrayed a man sleeping on a large stone, while around him there were all kinds of nightmares, who become living beings. With this allegory, Goya was referring to tragedies that involved Europe in his time, the end of the eighteenth century. But the same image can be the emblem of other tragedies closer to our days, nightmares born from intolerance, incomprehension of different people, from the illusion of intellectual, religious or racial superiority. The history of the witch hunting is an example of how an ancient nightmare is recurring over the centuries in different forms. In times of crisis, it is seeking a scapegoat for the evils that afflict society. So "the other", the incarnation of evil, must be isolated and eliminated. This irrational attitude common to primitive cultures to the so-called "civilization" modern and post-modern. The witch hunting was break out in different locations of Western Europe, between the Middle Ages and the Baroque age. The most affected areas were still dominated by particular cultures or on the border between nations in conflict for religious reasons or for political interests. Subtly, the rulers of this or that nation shake the specter of invisible and diabolical enemy to unleash fear and consequent reaction: the denunciation, persecution, extermination of witches.