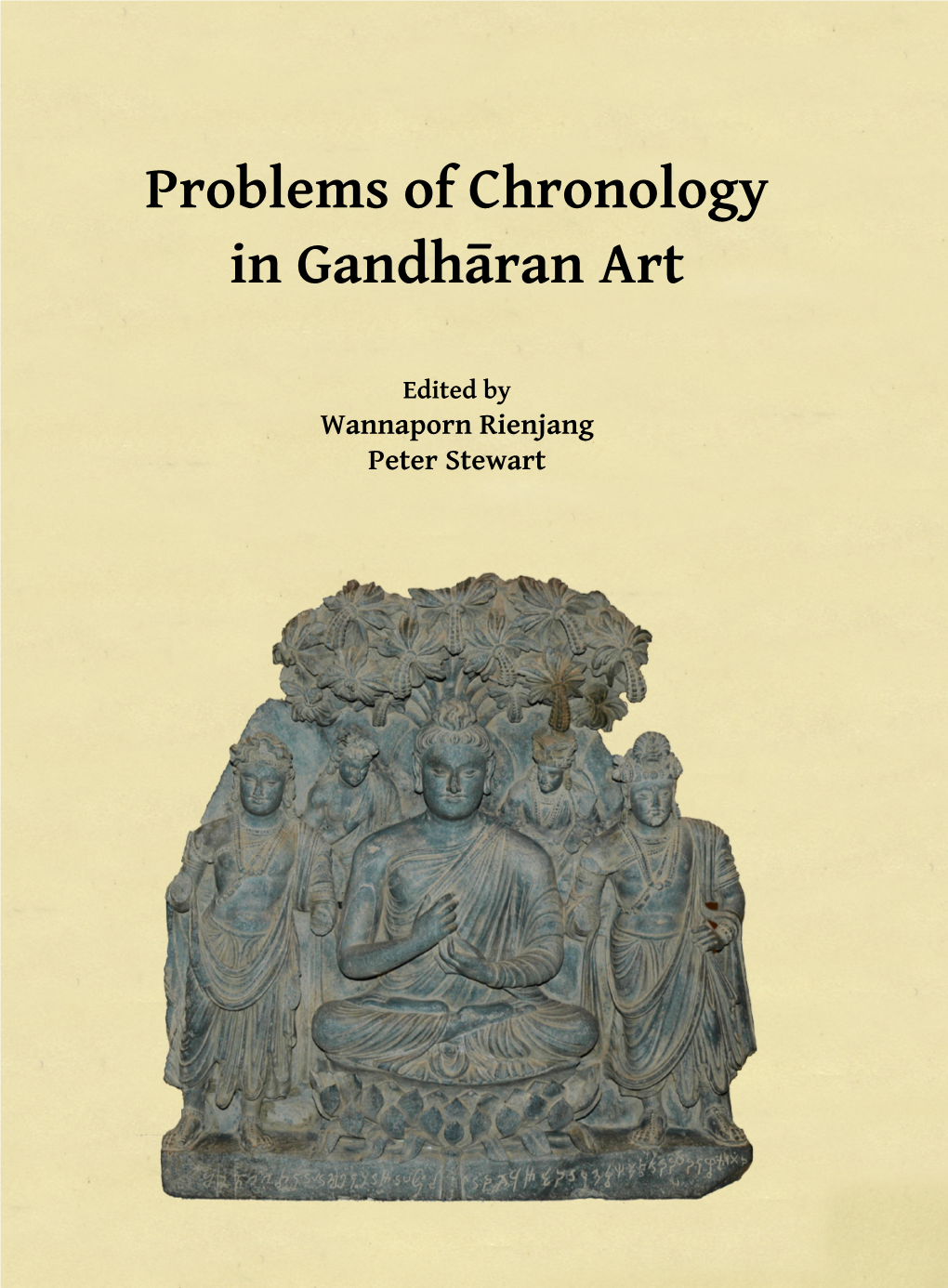

Problems of Chronology in Gandhāran Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Thesis

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Imagining Afghanistan British Foreign Policy and the Afghan Polity, 18081878 Bayly, Martin Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 This electronic theses or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Title: Imagining Afghanistan: British Foreign Policy and the Afghan Polity, 1808‐1878 Author: Martin Bayly The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. -

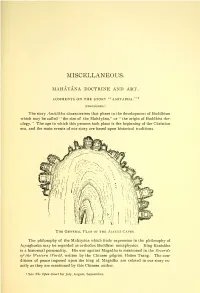

The Mahayana Doctrine and Art. Comments on the Story of Amitabha

MISCEIvIvANEOUS. MAHAYANA DOCTRINE AND ART. COMMENTS ON THE STORY "AMITABHA."^ (concluded.) The story Amitabha characterises that phase in the development of Buddhism which may be called " the rise of the Mahayana," or " the origin of Buddhist the- ology." The age in which this process took place is the beginning of the Christian era, and the main events of our story are based upon historical traditions. The General Plan of the Ajant.v Caves. The philosophy of the Mahayana which finds expression in the philosophy of Acvaghosha may be regarded as orthodox Buddhist metaphysics. King Kanishka is a historical personality. His war against Magadha is mentioned in the Records of the Western IVorld, written by the Chinese pilgrim Hsiien Tsang. The con- ditions of peace imposed upon the king of Magadha are related in our story ex- actly as they are mentioned by this Chinese author. 1 See The Open Court for July, August, September. 622 THE OPEN COURT. The monastic life described in the first, second, and fifth chapters of the story Amitdbha is a faithful portrayal of the historical conditions of the age. The ad- mission and ordination of monks (in Pali called Pabbajja and Upasampada) and the confession ceremony (in Pfili called Uposatha) are based upon accounts of the MahSvagga, the former in the first, the latter in the second, Khandaka (cf. Sacred Books of the East, Vol. XIII.). A Mother Leading Her Child to Buddha. (Ajanta caves.) Kevaddha's humorous story of Brahma (as told in The Open Cozirt, No. 554. pp. 423-427) is an abbreviated account of an ancient Pali text. -

Greece, the Mother of All Religious Art

GREECE, THE MOTHER OF ALL RELIGIOUS ART BY THE EDITOR. the of eternal principles we may IF revelation means discovery justly declare that the Greek nation has been the medium for the revelation of art to mankind as well as the founder of science. The Greek style of literature, Greek methods of artistic represen- tation. Greek modes of thought have become standards and are therefore in this sense called "classical." We stand on the shoul- ders of the ancient Greeks, and whatever we accomplish is but a continuing- of their work, a building higher upon the foundations they have laid. This is true of sculpture, of poetry and of the basic principle of the science of thought, of logic, and also of mathematics. Euclid, more than Leviticus or Deuteronomy, is a book inspired by God.^ Whatever the non-Euclideans- may have to criticize in the outlines of Euclid's plane geometry, we must say that the author of this brief work is, in a definite and well-defined sense, the prophet of the laws that prevail in the most useful of all space- conceptions. By Euclid we understand not so much the author of the book that goes under his name, but the gist of the book itself, the thought of it, the conception of geometry and the principles which are embodied in it. In our recognition of Euclid's geometry we include his predecessors, whosoever they may have been. The man who for the first time in the history of mankind conceived the idea of points, lines, planes as immaterial quantities, as thought-constructions or whatever you may call the presentation of pure figures and their interdependence, was really a divinely inspired mind. -

Indus Valley Sites Were Discovered

How the Indus Valley sites were discovered. What were the first clues What did Charles Masson to the ancient city sites? find out? When? What had happened to What did Robert Brunton the things Charles do? Was this right? Why Masson saw by the time did he do it? Sir Alexander visited? What was Mr Banerji’s How did they know the discovery? sites were linked? In the Indian village of Harrappa there was a very old ruined castle built on a hill. Nobody knew who had lived there .......... Information Gap Activity http://www.collaborativelearning.org/indusvalley.pdf How the Indus Valley sites were discovered. Devised by Judith Evans now at Camelot Primary School in Southwark. We used this information gap in February 2015 when the project worked with teachers in Hoshiapur in the Punjab which is as close as you can get to the Indus valley without entering Pakistan, so we have brought it up to date and have produced a more effective question grid. We have also tried to simplify teacher instructions! There is a lot of source material available on the net and we recommend you look at Ilona Aronovsky’s Resources at: https://www.harappa.com/teach This activity is designed to be used, to explore what children know and promote group talk before looking at source material. Their are two ways to use the activity. Method One: Divide class into three sections. One section in pairs or threes work on Text A, one part on Text B etc. and fill in as much of the question grid as they can. -

Shankara: a Hindu Revivalist Or a Crypto-Buddhist?

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Religious Studies Theses Department of Religious Studies 12-4-2006 Shankara: A Hindu Revivalist or a Crypto-Buddhist? Kencho Tenzin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/rs_theses Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Tenzin, Kencho, "Shankara: A Hindu Revivalist or a Crypto-Buddhist?." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2006. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/rs_theses/4 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Religious Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religious Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SHANKARA: A HINDU REVIVALIST OR A CRYPTO BUDDHIST? by KENCHO TENZIN Under The Direction of Kathryn McClymond ABSTRACT Shankara, the great Indian thinker, was known as the accurate expounder of the Upanishads. He is seen as a towering figure in the history of Indian philosophy and is credited with restoring the teachings of the Vedas to their pristine form. However, there are others who do not see such contributions from Shankara. They criticize his philosophy by calling it “crypto-Buddhism.” It is his unique philosophy of Advaita Vedanta that puts him at odds with other Hindu orthodox schools. Ironically, he is also criticized by Buddhists as a “born enemy of Buddhism” due to his relentless attacks on their tradition. This thesis, therefore, probes the question of how Shankara should best be regarded, “a Hindu Revivalist or a Crypto-Buddhist?” To address this question, this thesis reviews the historical setting for Shakara’s work, the state of Indian philosophy as a dynamic conversation involving Hindu and Buddhist thinkers, and finally Shankara’s intellectual genealogy. -

I the GIANT BUDDHA STATUES in BAMIYAN Description, History And

I THE GIANT BUDDHA STATUES IN BAMIYAN Catharina Blänsdorf, Michael Petzet Description, History and State of Conservation before the Destruction in 2001 The Bamiyan valley, 230 km northwest of Kabul and 2500 seated Buddhas, 55 meter Buddha and surrounding m above sea-level, separates the Hindu Kush from the Koh- caves, Kakrak Valley caves including the niche of the i-Baba mountains. The city of Bamiyan is the centre of the standing Buddha, Qoul-I Akram Caves in the Fuladi valley and the largest settlement of the Hazarajat. From Valley, Kalai Ghamai Caves in the Fuladi Valley, Shahr- West to East, the Bamiyan river runs through the valley. i-Zuhak, Qallay Kaphari A, Qallay Kaphari B, Shahr-i- The Cultural Landscape and Archaeological Remains of the Ghulghulah. Bamiyan Valley were inscribed on the World Heritage List 2. Recommends that the State Party make every effort in July 2003 and at the same time placed on the List of World to guarantee an adequate legal framework for the Heritage in Danger: protection and conservation of the Bamiyan Valley; 3. Further urges the international community and various organizations active in the field of heritage protection The World Heritage Committee, in the Bamiyan Valley to continue its co-operation and assistance to the Afghan authorities to enhance the 1. Inscribes the Cultural Landscape and Archaeological conservation and protection of the property; Remains of the Bamiyan Valley, Afghanistan, on the World Heritage List on the basis of cultural criteria (i), 4. Recognizing the significant and persisting danger posed (ii), (iii), (iv) and (vi): by anti-personnel mines in various areas of the Bamiyan Valley and noting the request from the Afghan authorities Criterion (i): The Buddha statues and the cave art in that all cultural projects include funds for demining; Bamiyan Valley are an outstanding representation of the Gandharan School in Buddhist art in the Central Asian 5. -

Indus Valley Civilization: Enigmatic, Exemplary, and Undeciphered Charise Joy Javonillo College of Dupage

ESSAI Volume 8 Article 21 4-1-2011 Indus Valley Civilization: Enigmatic, Exemplary, and Undeciphered Charise Joy Javonillo College of DuPage Follow this and additional works at: http://dc.cod.edu/essai Recommended Citation Javonillo, Charise Joy (2010) "Indus Valley Civilization: Enigmatic, Exemplary, and Undeciphered," ESSAI: Vol. 8, Article 21. Available at: http://dc.cod.edu/essai/vol8/iss1/21 This Selection is brought to you for free and open access by the College Publications at [email protected].. It has been accepted for inclusion in ESSAI by an authorized administrator of [email protected].. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Javonillo: Indus Valley Civilization Indus Valley Civilization: Enigmatic, Exemplary, and Undeciphered by Charise Joy Javonillo (Anthropology 1120) Introduction mong the four great ancient civilizations of the Old World, the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC) has the distinction of being the most enigmatic of this notable group (Kenoyer and AMeadow, 2000). Mindful of the inevitable comparisons to its better represented, recorded, and studied Western contemporaries Mesopotamia and Egypt, four major comparable aspects of the Indus Valley will be presented and discussed in this review. Beginning with settlement patterns, special attention is paid to Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro and specifically to the urban layout of these two exemplary cities. Second is the Indus’ sphere of influence as suggested by possible interaction with Mesopotamia, including motifs found in artwork and seals. Next is a synthesis and discussion about the current debate over the Indus Valley script and its decipherment. Lastly, possible theories are reviewed regarding the collapse and disappearance of the IVC. -

Central Asian Contacts and Their Results

Central Asian Contacts and their Results The period around 200 BCE did not witness an empire as large as Mauryas but is regarded as an important period in terms of the intimate and widespread contacts between Central Asia and India. In Eastern India, Central India and the Deccan, the Mauryas were succeeded by a number of native rulers such as the Sungas, the Kanvas and the Satavahanas. In north-western India, the Mauryas were succeeded by a number of ruling dynasties from Central Asia. Get a comprehensive note on the Mauryas for the IAS exam in the linked article. Indo-Greeks/Bactrian Greeks A series of invasions took place from about 200 BCE. The first to cross the Hindukush were the Greeks, who ruled Bactria, lying south of the Oxus river in the area covered by north Afghanistan. One of the important causes of invasion was the weakness of the Seleucid empire, which had been established in Bactria and the adjoining areas of Iran called Parthia. Due to the growing pressure from the Scythian tribes, the later Greek rulers were unable to hold their power in this area. The construction of the Chinese wall prevented the Scythians from entering China. So, their attention turned towards Greeks and Parthians. Pushed by the Scythian tribes, the Bactrian Greeks were forced to invade India. The successors of Ashoka were too weak to thwart the attack. • In the beginning of the 2nd century BCE, the Indo-Greeks/Bactrian Greeks were the first to invade India. • The Indo-Greeks occupied a large part of north-western India, much larger than that conquered by Alexander. -

2.IJHAMS-An Analytical Study on Emperors Asoka, Kanishka And

BEST: International Journal of Humanities, Arts, Medicine and Sciences (BEST: IJHAMS) ISSN (P): 2348-0521, ISSN (E): 2454-4728 Vol. 6, Issue 1, Jan 2018, 13-20 © BEST Journals AN ANALYTICAL STUDY ON EMPERORS ASOKA, KANISHKA AND HARSHA D. M. L. HARSHIKA BANDARA DASANAYAKA Assistant Lecture, Department of Pāli & Buddhist Studies, University of Ruhuna, Matara, Sri Lanka ABSTRACT Among the many kings who extended their patronage to Buddhism, the most prominent are Asoka, Kaniska and Harsha. Asoka was the person that made Buddhism a world religion. It was during his time well known nine missions were sent to various countries. Many inscriptions to impart the knowledge of morals were erected everywhere in his kingdom. After Ashoka a Kushana king called Kaniska supported Sarvastivada School, although it was during his times that the first Mahayana Sutras marked their appearance. King Harsha Wardhana was also a great patron of Buddhism in India. Asoka (268-232) is mentioned by historians as ‘the greatest of kings’, ‘not because of the physical extent of his empire, extensive as it was, but because of his character as a man, the ideals for which he stood and the principals by which he governed. Whatever religion Asoka believed in before his deeply moving experience of Kalinga war, he had converted himself to Buddhism at the time of third council. His conversion to Buddhism is compared by Rhys Davids with the Roman Emperor Constantine’s to Christianity. 1 His pilgrimages to the Buddhist sites were followed by erection of pillars with inscriptions that record the historical significance of those places. -

Pax Pamir: Second Edition

Pax Pamir: Second Edition Rules of Play In Pax Pamir, each player assumes the role of a nine- teenth-century Afghan leader attempting to forge a new state after the collapse of the Durrani Empire. Western histories often call this period “The Great Game” because of the role played by the Europeans who attempted to use Central Asia as a theater for their own rivalries. In this game, those empires are viewed strictly from the perspective of the Afghans who sought to manipulate the interloping ferengi (foreigners) for their own purposes. In terms of gameplay, Pax Pamir is a pretty straightfor- ward tableau builder. Players will spend most of their turns purchasing cards from a central market and then playing those cards in front of them in a single row called a court. Playing cards adds units to the game’s map and grants access to additional actions that can be taken to disrupt other players and influence the course of the game. That last point is worth emphasizing. Though everyone is building their own row of cards, the game offers many ways for players to interfere with each other, both directly and indirectly. To survive, players will organize into coalitions. In the game, these coalitions are identified chiefly by their sponsors. Two of the coalitions (British and Russian) are supported by European powers. The third coalition (Afghan) is backed by nativist elements who want to end European involvement in the region. Throughout the game, the different coalitions will be evaluated when a special event card, called a Dominance Check, is resolved. -

Mohenjo-Daro

IDOL Institute of Distance and Online Learning ENHANCE YOUR QUALIFICATION, ADVANCE YOUR CAREER. 2 B.A.English HISTORY-I Course Code: BAQ111 Semester: First SLM Unit : 2 E-Lesson: 2 www.cuidol.in Unit-2(BAQ111) All right are reserved with CU-IDOL HISTORY-I OBJECTIVES INTRODUCTION 3 After studying this unit, you will be able to: Excavation of Mohenzodaro and Harappa, Analyse the extent of Harappa culture. by R.D. Banerjee and Dayaram Sahani, was the most exhilarating event of the 20th century A.D. for the Indian historians Explain the causes for the decline of Harappa culture www.cuidol.in Unit-2(BAQ111)Q 111) INSTITUTEAll right OFare DISTANCE reserved ANDwith ONLINECU-IDOL LEARNING TOPICS TO BE COVERED 4 > Origin and Extent of Harappa Civilisation > Discovery & Time Span > Other Indus Valley Civilization HISTORY > Main Features Of Harappan Civilization - I https://note-world.blogspot.com/2017/08/harappan-civilization-and-major-centers.html www.cuidol.in Unit-2(BAQ111) All right are reserved with CU-IDOL ORIGIN AND EXTENT OF HARAPPA CIVILISATION 5 Ancient Indian History would have been in its dark phase if it had not explored the urban cities and culture in the Valley of Indus River and its tributaries. Discovery of the Indus civilisation which was the contemporary of ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia gives a proud moment to all Indians to write their history as rich and long back to the dates around 3000 BCE. It’s large extent and glory in socio-economic life, rich art and culture, scientific town planning have uplifted the Indian history into a great height that researchers expects more discoveries to prove its genuine history and culture to the whole world. -

When Herakles Followed the Buddha: Power, Protection, and Patronage in Gandharan Art

WHEN HERAKLES FOLLOWED THE BUDDHA: POWER, PROTECTION, AND PATRONAGE IN GANDHARAN ART Jonathan Homrighausen Jesuit School of Theology, Berkeley ong before the twenty-first century adage that “the and Iranian mythological figures and artistic styles. L world is flat,” ancient empires and trade routes Gandharan Buddhist art also incorporates Hindu enabled cultural globalization of a kind quite familiar deities such as Shiva (Quagliotti 2011). The fusion of to us today. Modern buzzwords like ‘syncretism’ and such varied elements makes the study of Gandharan ‘alterity/otherness’ apply to these ancient cultures as art a vibrant field involving many cultures, but also much as they do to modern ones. The art of Gandha- can make it difficult to determine the provenance of ra in the 1st to 5th century Indian subcontinent offers particular iconographic motifs. many examples: coins, sculpture, and architecture Graeco-Roman artistic culture first spread into depicting scenes from Indic mythologies, but sharing Gandhara through the conquests of Alexander the an iconographic vocabulary with Graeco-Roman and Great (335–323 BCE) and the settlers he left behind in Iranian Zoroastrian arts and religions. This article ex- Bactria. The Hellenistic successor states declined, to amines Herakles’ iconographic journey to India and be replaced in Bactria and Gandhara (territories en- his transformation into Vajrapani, the bodyguard of compassing northeastern Afghanistan and northern the Buddha. In Gandharan sculptural reliefs depict- Pakistan and India) by the Kushan empire [Fig. 1]. In ing events from the life of the Buddha, the Heraklean the Kushan period, Classical artistic influence contin- Vajrapani serves as a sacred icon embodying the Bud- ued (Nehru, pp.