Table of Contents Item Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Auction Will Take Place at 9 A.M. (+8 G.M.T.) Sunday 18Th October 2020 at 2/135 Russell St, Morley, Western Australia

The Auction will take place at 9 a.m. (+8 G.M.T.) Sunday 18th October 2020 at 2/135 Russell St, Morley, Western Australia. Viewing of lots will take place on Saturday 17th October 9am to 4pm & Sunday 18th October 7:00am to 8:45am, with the auction taking place at 9am and finishing around 5:00pm. Photos of each lot can be viewed via our ‘Auction’ tab of our website www.jbmilitaryantiques.com.au Onsite registration can take place before & during the auction. Bids will only be accepted from registered bidders. All telephone and absentee bids need to be received 3 days prior to the auction. Online registration is via www.invaluable.com. All prices are listed in Australian Dollars. The buyer’s premium onsite, telephone & absentee bidding is 18%, with internet bidding at 23%. All lots are guaranteed authentic and come with a 90-day inspection/return period. All lots are deemed ‘inspected’ for any faults or defects based on the full description and photographs provided both electronically and via the pre-sale viewing, with lots sold without warranty in this regard. We are proud to announce the full catalogue, with photographs now available for viewing and pre-auction bidding on invaluable.com (can be viewed through our website auction section), as well as offering traditional floor, absentee & phone bidding. Bidders agree to all the ‘Conditions of Sale’ contained at the back of this catalogue when registering to bid. Post Auction Items can be collected during the auction from the registration desk, with full payment and collection within 7 days of the end of the auction. -

E6 D20 Stalker Zone Stalker

E6 D20 Stalker Zone Stalker. Enjoy your stay. Welcome to the D20 Stalker Game supplement for the D20 Modern system. The Zone: was relatively peaceful until sometime Before the 1986 disaster, the remote areas around 2001, when a bus full of tourists in around Chernobyl and Pripyat were used the zone disappeared. The incident by the Soviet Union for research and prompted the government to fully restrict development of psychotropic weapons the zone to civilians. In 2011, stalkers and study of the noospher[1] One of the reported encountering zombies who spoke earliest such programs was undertaken at garbled English, revealing the fate of the Limansk-13, a secret city where top Soviet tourists. scientists experimented with radiowaves, The first experiment in affecting human in order to harness them as a tool, to psyche on a massive scale took place on create unflinching loyalty to the Union in March 4, 2006[3]. It lasted two full hours all affected people. before it was shut down, likely due to However, the research was not safe. A unforeseen developments. A month later, surge in energy consumption during one on April 12, the experiment was performed of the experiments on April 26, 1986 was again and this time it continued until its one of the main reasons Reactor 4 completion[4]. However, it did not have the exploded. In response to the incident, the desired effect - instead, the generators USSR evacuated Pripyat and settlements in created a rift in the noosphere, allowing it the neighboring areas, until the Zone to directly affect the biosphere, creating a became almost totally deserted, save for a large area where physical laws were few die hard citizens (including the outright broken and mysterious Forester) and scientific teams working in phenomena not understood by modern secret laboratories. -

Consejo De Seguridad Distr

Naciones Unidas S/2018/1002 Consejo de Seguridad Distr. general 9 de noviembre de 2018 Español Original: inglés Carta de fecha 7 de noviembre de 2018 dirigida al Presidente del Consejo de Seguridad por el Presidente del Comité del Consejo de Seguridad dimanante de las resoluciones 751 (1992) y 1907 (2009) relativas a Somalia y Eritrea En nombre del Comité del Consejo de Seguridad dimanante de las resoluciones 751 (1992) y 1907 (2009) relativas a Somalia y Eritrea, y de conformidad con el párrafo 48 de la resolución 2385 (2017) del Consejo de Seguridad, tengo el honor de transmitir adjunto el informe sobre Somalia del Grupo de Supervisión para Somalia y Eritrea. A ese respecto, el Comité agradecería que la presente carta y el informe se señalaran a la atención de los miembros del Consejo de Seguridad y se publicaran como documento del Consejo. (Firmado) Kairat Umarov Presidente Comité del Consejo de Seguridad dimanante de las resoluciones 751 (1992) y 1907 (2009) relativas a Somalia y Eritrea 18-16126 (S) 091118 131118 *1816126* S/2018/1002 Carta de fecha 2 de octubre de 2018 dirigida al Presidente del Comité del Consejo de Seguridad dimanante de las resoluciones 751 (1992) y 1907 (2009) relativas a Somalia y Eritrea por el Grupo de Supervisión para Somalia y Eritrea De conformidad con el párrafo 48 de la resolución 2385 (2017) del Consejo de Seguridad, tenemos el honor de transmitir adjunto el informe sobre Somalia del Grupo de Supervisión para Somalia y Eritrea. (Firmado) James Smith Coordinador Grupo de Supervisión para Somalia y Eritrea (Firmado) Jay Bahadur Experto en grupos armados (Firmado) Charles Cater Experto en recursos naturales (Firmado) Mohamed Abdelsalam Babiker Experto en asuntos humanitarios (Firmado) Brian O’Sullivan Experto en grupos armados/cuestiones marítimas (Firmado) Nazanine Moshiri Experta en armas (Firmado) Richard Zabot Experto en armas 2/160 18-16126 S/2018/1002 Resumen En 1992 se impuso a Somalia un embargo de armas general y completo en virtud de la resolución 733 (1992) del Consejo de Seguridad. -

AWE and BEAUTY Joint Proof and Experimental Unit – a History Doctor Steven Anthony Schmied

AWE AND BEAUTY Joint Proof And Experimental Unit – A History Doctor Steven Anthony Schmied AWE AND BEAUTY A History of the Joint Proof and Experimental Unit Doctor Steven Anthony Schmied © Commonwealth Of Australia 2019 First Published 2019 This work is copyright. Permission is given by the Commonwealth of Australia for this publication to be copied royalty free within Australia solely for educational purposes. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced for commercial purposes. Designed and produced by Big Sky Publishing www.bigskypublishing.com.au AWE AND BEAUTY A History of the Joint Proof and Experimental Unit Doctor Steven Anthony Schmied www.bigskypublishing.com.au CONTENTS Chapter 1. Awe And Beauty ..........................................................................................................................................04 Chapter 2. Graytown ....................................................................................................................................................12 Chapter 3. Port Wakefield .............................................................................................................................................46 Chapter 4. Orchard Hills ..............................................................................................................................................73 Chapter 5. The Work ....................................................................................................................................................75 -

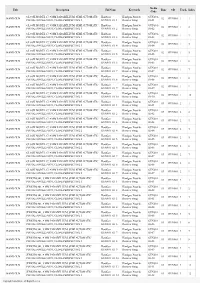

Title Description Filename Keywords Media Code Time CD Track Index

Media Title Description FileName Keywords Time CD Track Index Code GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC HandGun Handgun, Pistol & GUNS01- HAND GUN :02 GUNS01 1 1 PISTOL: SINGLE SHOT, CLOSE PERSPECTIVE 1 GUNS01_01_1 Revolver Firing 01-01 GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC HandGun Handgun, Pistol & GUNS01- HAND GUN :02 GUNS01 1 2 PISTOL: SINGLE SHOT, CLOSE PERSPECTIVE 1 GUNS01_01_2 Revolver Firing 01-02 GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC HandGun Handgun, Pistol & GUNS01- HAND GUN :02 GUNS01 1 3 PISTOL: SINGLE SHOT, CLOSE PERSPECTIVE 1 GUNS01_01_3 Revolver Firing 01-03 GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC HandGun Handgun, Pistol & GUNS01- HAND GUN :02 GUNS01 1 4 PISTOL: SINGLE SHOT, CLOSE PERSPECTIVE 1 GUNS01_01_4 Revolver Firing 01-04 GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC HandGun Handgun, Pistol & GUNS01- HAND GUN :02 GUNS01 1 5 PISTOL: SINGLE SHOT, CLOSE PERSPECTIVE 1 GUNS01_01_5 Revolver Firing 01-05 GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC HandGun Handgun, Pistol & GUNS01- HAND GUN :02 GUNS01 1 6 PISTOL: SINGLE SHOT, CLOSE PERSPECTIVE 1 GUNS01_01_6 Revolver Firing 01-06 GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC HandGun Handgun, Pistol & GUNS01- HAND GUN :02 GUNS01 1 7 PISTOL: SINGLE SHOT, CLOSE PERSPECTIVE 1 GUNS01_01_7 Revolver Firing 01-07 GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC HandGun Handgun, Pistol & GUNS01- HAND GUN :02 GUNS01 1 8 PISTOL: SINGLE SHOT, CLOSE PERSPECTIVE 1 GUNS01_01_8 Revolver Firing 01-08 GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC -

6 North and South Ossetia: Old Conflicts and New Fears

6 North and South Ossetia: Old conflicts and new fears Alan Parastaev Erman village in the high Caucasus mountains of South Ossetia PHOTO: PETER NASMYTH Summary The main source of weapons in South Ossetia during the conflict with Georgian forces in the early 1990s was Chechnya, but towards the end of the conflict arms were also obtained from Russian troops in North Ossetia. Following the end of the conflict in 1992, the unrecognised Republic of South Ossetia began to construct its own security structures. The government has made some attempts to control SALW proliferation and collect weapons from the population, as has the OSCE, though these programmes have had limited success. In North Ossetia it was much easier to acquire weapons from Russian military sources than in the South. North Ossetia fought a short war against the Ingush in 1992, and though relations between the two are now stable, North Ossetia is still very sensitive to events elsewhere in the North Caucasus. Recently, however, the increase in Russian military activity in the region has acted as a stabilising factor. Unofficial estimates of the amount of SALW in North Ossetia range between 20,000 and 50,000. 2 THE CAUCASUS: ARMED AND DIVIDED · NORTH AND SOUTH OSSETIA The years of The events at the end of the 1980s ushered in by perestroika – the move by the leader- conflict ship of the CPSU towards the democratisation of society – had an immediate impact on the social and political situation in South Ossetia and Georgia as a whole. In both Tbilisi and the South Ossetian capital Tskhinval national movements sprang to life which would in time evolve into political parties and associations. -

Sound Ideas Guns Sound Effects Series Complete Track and Index

Sound Ideas Guns Sound Effects Series Complete Track and Index Listing CD # Tr/In Title & Description Time GUNS01 01-01 HAND GUN GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC PISTOL: SINGLE SHOT, CLOSE PERSPECTIVE 1 :02 GUNS01 01-02 HAND GUN GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC PISTOL: SINGLE SHOT, CLOSE PERSPECTIVE 1 :02 GUNS01 01-03 HAND GUN GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC PISTOL: SINGLE SHOT, CLOSE PERSPECTIVE 1 :02 GUNS01 01-04 HAND GUN GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC PISTOL: SINGLE SHOT, CLOSE PERSPECTIVE 1 :02 GUNS01 01-05 HAND GUN GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC PISTOL: SINGLE SHOT, CLOSE PERSPECTIVE 1 :02 GUNS01 01-06 HAND GUN GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC PISTOL: SINGLE SHOT, CLOSE PERSPECTIVE 1 :02 GUNS01 01-07 HAND GUN GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC PISTOL: SINGLE SHOT, CLOSE PERSPECTIVE 1 :02 GUNS01 01-08 HAND GUN GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC PISTOL: SINGLE SHOT, CLOSE PERSPECTIVE 1 :02 GUNS01 01-09 HAND GUN GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC PISTOL: SINGLE SHOT, CLOSE PERSPECTIVE 1 :02 GUNS01 01-10 HAND GUN GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC PISTOL: SINGLE SHOT, CLOSE PERSPECTIVE 1 :02 GUNS01 02-01 HAND GUN GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC PISTOL: SINGLE SHOT, CLOSE PERSPECTIVE 2 :03 GUNS01 02-02 HAND GUN GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC PISTOL: SINGLE SHOT, CLOSE PERSPECTIVE 2 :03 GUNS01 02-03 HAND GUN GLOCK MODEL 17, 9 MM PARABELLUM, SEMI AUTOMATIC PISTOL: -

Inventory to Archival Boxes in the Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress

INVENTORY TO ARCHIVAL BOXES IN THE MOTION PICTURE, BROADCASTING, AND RECORDED SOUND DIVISION OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Compiled by MBRS Staff (Last Update December 2017) Introduction The following is an inventory of film and television related paper and manuscript materials held by the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress. Our collection of paper materials includes continuities, scripts, tie-in-books, scrapbooks, press releases, newsreel summaries, publicity notebooks, press books, lobby cards, theater programs, production notes, and much more. These items have been acquired through copyright deposit, purchased, or gifted to the division. How to Use this Inventory The inventory is organized by box number with each letter representing a specific box type. The majority of the boxes listed include content information. Please note that over the years, the content of the boxes has been described in different ways and are not consistent. The “card” column used to refer to a set of card catalogs that documented our holdings of particular paper materials: press book, posters, continuity, reviews, and other. The majority of this information has been entered into our Merged Audiovisual Information System (MAVIS) database. Boxes indicating “MAVIS” in the last column have catalog records within the new database. To locate material, use the CTRL-F function to search the document by keyword, title, or format. Paper and manuscript materials are also listed in the MAVIS database. This database is only accessible on-site in the Moving Image Research Center. If you are unable to locate a specific item in this inventory, please contact the reading room. -

Army Special Forces Legend

Military Despatches Vol 45 March 2021 Thanks, but no thanks 10 dangerous roles in the military It pays to be a winner The US Navy SEALs An offer you can’t refuse Did the US Military and the Mafia collaborate? Colonel Arthur ‘Bull’ Simons US Army Special Forces legend For the military enthusiast CONTENTS March 2021 Page 14 Click on any video below to view How much do you know about movie theme songs? Take our quiz and find out. Hipe’s Wouter de The old South African Goede interviews former Defence Force used 28’s gang boss David a mixture of English, Williams. Afrikaans, slang and techno-speak that few Special Forces - US Navy SEALS outside the military could hope to under- 46 stand. Some of the terms Features Changes to the engine room were humorous, some 6 were clever, while others The Sea Cadets announce new were downright crude. Ten dangerous military roles appointments. These are ten military roles in 48 history that you did not want. Remembrance Day Part of Hipe’s “On the 22 32 Seaman Piper Pauwels from couch” series, this is an Who’s running the show? It’s not really a game TS Rook researches the mean- interview with one of The nine people that became How simulators are changing ing of Remembrance Day. author Herman Charles Chief of the SADF. the way the military trains. 50 Bosman’s most famous 24 36 characters, Oom Schalk Memories of a Sea Cadet An offer you can’t refuse Long distance air mail Deene Collopy, Country Man- A taxi driver was shot Lourens. -

Index of Watermark Classes and Subclasses

INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF PAPER HISTORIANS INTERNATIONAL STANDARD FOR THE REGISTRATION OF PAPERS WITH OR WITHOUT WATERMARKS VERSION 2.1.1 (2013) 1/84 IPH Standard 2.1.1 2013 22.10.2013 INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF PAPER HISTORIANS INTERNATIONAL STANDARD FOR THE REGISTRATION OF PAPERS WITH OR WITHOUT WATERMARKS VERSION 2.1.1 (2013) INTERNATIONAL STANDARD FOR THE REGISTRATION OF PAPERS WITH OR WITHOUT WATERMARKS 1 Introduction Practical use of the IPH Registration Standard Since Version 2.0 was published in 1997, computer The comparability of paper data is ensured even if only science has made a tremendous progress. The web and a few, incomplete data are available. In other words: PC performances, exceeding the power of the former Nothing but those data should be registrated which giant computers, have become routine. In the same are unmistakable and assignable; all other criteria time, the interest in historical paper analysis has grown may be omitted, i.e. the corresponding labels should world-wide, together with a demand for more accurate remain void. The Standard prescribes, for basic regis- results. Therefore, the IPH standard had to be revised. tration, only data which serve to identify an item and the corresponding data file. This will minimize the Many of the new watermark collections, especially in registration time involved. Europe, use criteria of their own and different digitali- zing systems. All the more, a normalization of the crite- 2 Function of the Standard ria becomes a must, especially in view of a scholarly standard of the data to be obtained, and the IPH is 2.1 Identification of papers aiming at an international recognition of its Registra- tion Standard. -

Hand-Grenade

Military Accessories for Russian Motorcycles Part XVI: Decorative (Deco) Russian WW-II Hand-Grenades Ernie Franke [email protected] 10/2011 Russian Hand-Grenades of World War-Two (WW-II) • Which Russian Hand-Grenades Were Available in WW-II? Various Models (below) • Were Stick Hand-Grenades Used by the Russians? Yes • Grenade Evolution –F-1 Fragmentation Hand-Grenade –RGD-33 Fragmentation (with sleeve) Hand-Grenade –RG-41 Fragmentation Hand-Grenade –RG-42 Fragmentation (with sleeve) Hand-Grenade –RG-42V Fragmentation (with sleeve) Hand-Grenade Hand-Grenades –ROG-43 Fragmentation (with sleeve) Hand-Grenade –RGU-38 Experimental Fragmentation Hand-Grenade –RGU-39 Experimental Fragmentation Hand-Grenade –RPG-40 Anti-Tank Hand Grenade –RPG-41 / RGD-41 Anti-Tank Hand Grenade –RPG-43 Anti-Tank Hand Grenade Armor-Piercing –RPG-6 Anti-Tank Hand Grenade • Rifle-Grenade Evolution –VPGS-41 –VKG-42 • Grenade Pouches –Two and Three-Grenade Pouches • Decorative Grenades –Dummy Grenades –Wooden Models • Definitions –RG: Ручная Граната (Hand-Grenade) –RGD: Rutschnaia Granata Djagonow Hand Grenade of the Degtyarev design –RPG: ручная противотанковая граната (Anti-Tank Grenade) Just as in machine gun development, the suffix number of 2 Russian grenades indicated the year that the grenade was introduced. Russian Hand-Grenades • “Grenade" Derived from French Word for Pomegranate –Shrapnel Reminded Soldiers of the Seeds –During WW-I and beyond, Nicknamed ‘Pineapple’ because of Serrated Shell • Grenade Termed a ‘niche’ Weapon –Small Bomb: Used on the -

World War I Steel Monsters Head-To-Head

Military Despatches Vol 17 November 2018 World War I Commemorative Issue World War I Facts, figures and trivia Moth O Founder of the Memorable Order of Tin Hats An unsung hero Eugene Bullard, the first black fighter ace Steel Monsters The tanks of World War I Head-to-Head World War I weapons and equipment For the military enthusiast CONTENTS November 2018 Page 6 Click on any video below to view How much do you know about movie theme songs? Take our quiz and find out. Hipe’s Wouter de The old South African Goede interviews former Defence Force used 28’s gang boss David a mixture of English, Williams. Afrikaans, slang and World War I techno-speak that few outside the military Facts, figures and trivia could hope to under- 27 stand. Some of the terms Features Head-to-Head were humorous, some Is that a fact 38 were clever, while others 16 Some facts about World War I. Weapons & Equipment WWI were downright crude. We must remember them Short, sharp and to the point. This month we compare the Raymond Fletcher looks at the weapons and equipment of the significance of Remembrance 30 major combatants in the First Part of Hipe’s “On the Day and imagines what it must The story of Moth 0 World War. couch” series, this is an have been like to fight in the Early this year the Memorable ‘war to end all wars’. Order of Tin Hats celebrated interview with one of Quiz author Herman Charles its 90th anniversary. This is the 20 story of the man who began the 51 Bosman’s most famous Order.