Inland Fishes of California

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edna Assay Development

Environmental DNA assays available for species detection via qPCR analysis at the U.S.D.A Forest Service National Genomics Center for Wildlife and Fish Conservation (NGC). Asterisks indicate the assay was designed at the NGC. This list was last updated in June 2021 and is subject to change. Please contact [email protected] with questions. Family Species Common name Ready for use? Mustelidae Martes americana, Martes caurina American and Pacific marten* Y Castoridae Castor canadensis American beaver Y Ranidae Lithobates catesbeianus American bullfrog Y Cinclidae Cinclus mexicanus American dipper* N Anguillidae Anguilla rostrata American eel Y Soricidae Sorex palustris American water shrew* N Salmonidae Oncorhynchus clarkii ssp Any cutthroat trout* N Petromyzontidae Lampetra spp. Any Lampetra* Y Salmonidae Salmonidae Any salmonid* Y Cottidae Cottidae Any sculpin* Y Salmonidae Thymallus arcticus Arctic grayling* Y Cyrenidae Corbicula fluminea Asian clam* N Salmonidae Salmo salar Atlantic Salmon Y Lymnaeidae Radix auricularia Big-eared radix* N Cyprinidae Mylopharyngodon piceus Black carp N Ictaluridae Ameiurus melas Black Bullhead* N Catostomidae Cycleptus elongatus Blue Sucker* N Cichlidae Oreochromis aureus Blue tilapia* N Catostomidae Catostomus discobolus Bluehead sucker* N Catostomidae Catostomus virescens Bluehead sucker* Y Felidae Lynx rufus Bobcat* Y Hylidae Pseudocris maculata Boreal chorus frog N Hydrocharitaceae Egeria densa Brazilian elodea N Salmonidae Salvelinus fontinalis Brook trout* Y Colubridae Boiga irregularis Brown tree snake* -

Appendix E: Fish Species List

Appendix F. Fish Species List Common Name Scientific Name American shad Alosa sapidissima arrow goby Clevelandia ios barred surfperch Amphistichus argenteus bat ray Myliobatis californica bay goby Lepidogobius lepidus bay pipefish Syngnathus leptorhynchus bearded goby Tridentiger barbatus big skate Raja binoculata black perch Embiotoca jacksoni black rockfish Sebastes melanops bonehead sculpin Artedius notospilotus brown rockfish Sebastes auriculatus brown smoothhound Mustelus henlei cabezon Scorpaenichthys marmoratus California halibut Paralichthys californicus California lizardfish Synodus lucioceps California tonguefish Symphurus atricauda chameleon goby Tridentiger trigonocephalus cheekspot goby Ilypnus gilberti chinook salmon Oncorhynchus tshawytscha curlfin sole Pleuronichthys decurrens diamond turbot Hypsopsetta guttulata dwarf perch Micrometrus minimus English sole Pleuronectes vetulus green sturgeon* Acipenser medirostris inland silverside Menidia beryllina jacksmelt Atherinopsis californiensis leopard shark Triakis semifasciata lingcod Ophiodon elongatus longfin smelt Spirinchus thaleichthys night smelt Spirinchus starksi northern anchovy Engraulis mordax Pacific herring Clupea pallasi Pacific lamprey Lampetra tridentata Pacific pompano Peprilus simillimus Pacific sanddab Citharichthys sordidus Pacific sardine Sardinops sagax Pacific staghorn sculpin Leptocottus armatus Pacific tomcod Microgadus proximus pile perch Rhacochilus vacca F-1 plainfin midshipman Porichthys notatus rainwater killifish Lucania parva river lamprey Lampetra -

Marine Fish Culture

FAU Institutional Repository http://purl.fcla.edu/fau/fauir This paper was submitted by the faculty of FAU’s Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute. Notice: © 1998 Kluwer. This manuscript is an author version with the final publication available and may be cited as: Tucker, J. W., Jr. (1998). Marine fish culture. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers. MARINE FISH CULTURE by John W. Tucker, Jr., Ph.D. Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institution and Florida Institute of Technology, Melbourne KLUWER ACADEMIC PUBLISHERS Boston I Dordrecht I London Distributors for North, Central and South America: Kluwer Academic Publishers I 01 Philip Drive Assinippi Park Norwell, Massachusetts 02061 USA Telephone (781) 871-6600 Fax (781) 871-6528 E-Mail <[email protected]> Distributors for all other countries: Kluwer Academic Publishers Group Distribution Centre Post Office Box 322 3300 AH Dordrecht, THE NETHERLANDS Telephone 31 78 6392 392 Fax 31 78 6546 474 E-Mail <[email protected]> '' Electronic Services <http://www.wkap.nl> Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Tucker, John W., 1948- Marine fish culture I by John W. Tucker, Jr. p. em. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 0-412-07151-7 (alk. paper) 1. Marine fishes. 2. Fish-culture. I. Title. SH163.T835 1998 639.3'2--dc21 98-42062 CIP Copyright © 1998 by Kluwer Academic Publishers All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, photo copying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher, Kluwer Academic Publishers, I 0 I Philip Drive, Assinippi Park, Norwell, Massachusetts 02061 Printed on acid-free paper. -

Attachment Iii: Baseline Status and Cumulative Effects for the San Francisco Bay Listed Species

ATTACHMENT III: BASELINE STATUS AND CUMULATIVE EFFECTS FOR THE SAN FRANCISCO BAY LISTED SPECIES 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1: ALAMEDAWHIPSNAKE ............................................................................................ 6 1.1 CUMULATIVE EFFECTS ...................................................................................... 6 1.2 ENVIRONMENTAL BASELINE........................................................................... 6 1.2.1 Factors affecting species within the action area ............................................... 6 1.2.1.1 Urban development .................................................................................... 7 1.2.1.2 Fire suppression ......................................................................................... 9 1.2.1.3 Predation .................................................................................................... 9 1.2.1.4 Grazing practices ..................................................................................... 10 1.2.1.5 Non-native species ................................................................................... 10 1.2.2 Baseline Status ................................................................................................ 11 1.3 REFERENCES ...................................................................................................... 13 2: BAY CHECKERSPOT BUTTERFLY ....................................................................... 14 2.1 CUMULATIVE EFFECTS .................................................................................. -

Lake Tahoe Fish Species

Description: o The Lohonton cutfhroot trout (LCT) is o member of the Solmonidqe {trout ond solmon) fomily, ond is thought to be omong the most endongered western solmonids. o The Lohonton cufihroot wos listed os endongered in 1970 ond reclossified os threotened in 1975. Dork olive bdcks ond reddish to yellow sides frequently chorocterize the LCT found in streoms. Steom dwellers reoch l0 inches in length ond only weigh obout I lb. Their life spon is less thon 5 yeors. ln streoms they ore opportunistic feeders, with diets consisting of drift orgonisms, typicolly terrestriol ond oquotic insects. The sides of loke-dwelling LCT ore often silvery. A brood, pinkish stripe moy be present. Historicolly loke dwellers reoched up to 50 inches in length ond weigh up to 40 pounds. Their life spon is 5-14yeors. ln lokes, smoll Lohontons feed on insects ond zooplonkton while lorger Lohonions feed on other fish. Body spots ore the diognostic chorocter thot distinguishes the Lohonion subspecies from the .l00 Poiute cutthroot. LCT typicolly hove 50 to or more lorge, roundish-block spots thot cover their entire bodies ond their bodies ore typicolly elongoted. o Like other cufihroot trout, they hove bosibronchiol teeth (on the bose of tongue), ond red sloshes under their iow (hence the nome "cutthroot"). o Femole sexuol moturity is reoch between oges of 3 ond 4, while moles moture ot 2 or 3 yeors of oge. o Generolly, they occur in cool flowing woier with ovoiloble cover of well-vegetoted ond stoble streom bonks, in oreos where there ore streom velocity breoks, ond in relotively silt free, rocky riffle-run oreos. -

Report on the Monitoring of Radionuclides in Fishery Products (March 2011 - January 2015)

Report on the Monitoring of Radionuclides in Fishery Products (March 2011 - January 2015) April 2015 Fisheries Agency of Japan 0 1 Table of Contents Overview…………………………………………………………………………………………………. 8 The Purpose of this Report………………………………………………………………………………9 Part One. Efforts to Guarantee the Safety of Fishery Products………………………………………..11 Chapter 1. Monitoring of Radioactive Materials in Food; Restrictions on Distribution and Other Countermeasures………...…………………………………………………………………11 1-1-1 Standard Limits for Radioactive Materials in Food………………………………………...……11 1-1-2 Methods of Testing for Radioactive Materials………………………………………...…………12 1-1-3 Inspections of Fishery Products for Radioactive Materials…………………………...…………14 1-1-4 Restrictions and Suspensions on Distribution and Shipping ……………………………………..18 1-1-5 Cancellation of Restrictions on Shipping and Distribution………………………………………20 Box 1 Calculation of the Limits for Human Consumption……..………………………………………23 Box 2 Survey of Radiation Dose from Radionuclides in Foods Calculation of the Limits…………….24 Box 3 Examples of Local Government Monitoring Plan………………………………...…………….25 Chapter 2. Results of Radioactive Cesium Inspections for Fishery Products…………………………26 1-2-1 Inspection Results for Nationwide Fishery Products in Japan (in total)…………………………26 1-2-2 Inspection Results for Fukushima Prefecture Fishery Products (all)…………………………….27 1-2-3 Inspection Results for Fishery Products (all) from Outside Fukushima Prefecture……………...30 1-2-4 Trends within Fish Species……………………………………………………………………….32 1-2-5 Inspection Results for Main Target Fish Species of Fishing and Farming by Fiscal Year……….42 1-2-6 Radioactive Material Concentrations within Fish within 20 km of the Fukushima Daiichi NPS.46 Box 4 Fukushima Fishing Trials………………………………...……………………………………...47 1-2-7 Screening Test by Prefectural and Municipal Governments……………………………………..48 Chapter 3. Inspection for Radionuclides Other Than Radioactive Cesium……………………………49 1-3-1 Inspections for Radioactive Strontium etc. -

A Dissertation Entitled Evolution, Systematics

A Dissertation Entitled Evolution, systematics, and phylogeography of Ponto-Caspian gobies (Benthophilinae: Gobiidae: Teleostei) By Matthew E. Neilson Submitted as partial fulfillment of the requirements for The Doctor of Philosophy Degree in Biology (Ecology) ____________________________________ Adviser: Dr. Carol A. Stepien ____________________________________ Committee Member: Dr. Christine M. Mayer ____________________________________ Committee Member: Dr. Elliot J. Tramer ____________________________________ Committee Member: Dr. David J. Jude ____________________________________ Committee Member: Dr. Juan L. Bouzat ____________________________________ College of Graduate Studies The University of Toledo December 2009 Copyright © 2009 This document is copyrighted material. Under copyright law, no parts of this document may be reproduced without the expressed permission of the author. _______________________________________________________________________ An Abstract of Evolution, systematics, and phylogeography of Ponto-Caspian gobies (Benthophilinae: Gobiidae: Teleostei) Matthew E. Neilson Submitted as partial fulfillment of the requirements for The Doctor of Philosophy Degree in Biology (Ecology) The University of Toledo December 2009 The study of biodiversity, at multiple hierarchical levels, provides insight into the evolutionary history of taxa and provides a framework for understanding patterns in ecology. This is especially poignant in invasion biology, where the prevalence of invasiveness in certain taxonomic groups could -

07 Trites FB105(2)

Diets of Steller sea lions (Eumetopias jubatus) in Southeast Alaska, 1993−1999 Item Type article Authors Trites, Andrew W.; Calkins, Donald G.; Winship, Arliss J. Download date 29/09/2021 03:04:20 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/25538 ART & EQ UATIONS ARE LINKED 234 Abstract—The diet of Steller sea lions Diets of Steller sea lions (Eumetopias jubatus) (Eumetopias jubatus) was determined from 1494 scats (feces) collected at in Southeast Alaska, 1993−1999 breeding (rookeries) and nonbreeding (haulout) sites in Southeast Alaska from 1993 to 1999. The most common Andrew W. Trites1 prey of 61 species identified were wall- Donald G. Calkins2 eye pollock ( ), Theragra chalcogramma 1 Pacific herring (Clupea pallasii), Arliss J. Winship Pacific sand lance (Ammodytes hexa- Email address for A. W. Trites: [email protected] pterus), Pacific salmon (Salmonidae), 1 Marine Mammal Research Unit, Fisheries Centre arrowtooth flounder (Atheresthes sto- Room 247, AERL – Aquatic Ecosystems Research Laboratory mias), rockfish (Sebastes spp.), skates 2202 Main Mall, University of British Columbia (Rajidae), and cephalopods (squid Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z4 and octopus). Steller sea lion diets at the three Southeast Alaska rook- 2 Alaska Department of Fish and Game eries differed significantly from one 333 Raspberry Road another. The sea lions consumed the Anchorage, Alaska 99518-1599 most diverse range of prey catego- ries during summer, and the least diverse during fall. Diet was more diverse in Southeast Alaska during the 1990s than in any other region of Alaska (Gulf of Alaska and Aleutian Islands). Dietary differences between increasing and declining populations Steller sea lion (Eumetopias jubatus) rates of decline had the lowest diversi- of Steller sea lions in Alaska correlate populations in the Aleutian Islands ties of diet. -

Summary Report of Freshwater Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S

Summary Report of Freshwater Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 4—An Update April 2013 Prepared by: Pam L. Fuller, Amy J. Benson, and Matthew J. Cannister U.S. Geological Survey Southeast Ecological Science Center Gainesville, Florida Prepared for: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Atlanta, Georgia Cover Photos: Silver Carp, Hypophthalmichthys molitrix – Auburn University Giant Applesnail, Pomacea maculata – David Knott Straightedge Crayfish, Procambarus hayi – U.S. Forest Service i Table of Contents Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................................... ii List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................ v List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................ vi INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 1 Overview of Region 4 Introductions Since 2000 ....................................................................................... 1 Format of Species Accounts ...................................................................................................................... 2 Explanation of Maps ................................................................................................................................ -

Comparing Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Salmonid Aquaculture Production Systems: Status and Perspectives

sustainability Review Comparing Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Salmonid Aquaculture Production Systems: Status and Perspectives Gaspard Philis 1,* , Friederike Ziegler 2 , Lars Christian Gansel 1, Mona Dverdal Jansen 3 , Erik Olav Gracey 4 and Anne Stene 1 1 Department of Biological Sciences, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Larsgårdsvegen 2, 6009 Ålesund, Norway; [email protected] (L.C.G.); [email protected] (A.S.) 2 Agrifood and Bioscience, RISE Research Institutes of Sweden, Post box 5401, 40229 Gothenburg, Sweden; [email protected] 3 Section for Epidemiology, Norwegian Veterinary Institute, Pb 750 Sentrum, 0106 Oslo, Norway; [email protected] 4 Sustainability Department, BioMar Group, Havnegata 9, 7010 Trondheim, Norway; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +47-451-87-634 Received: 31 March 2019; Accepted: 27 April 2019; Published: 30 April 2019 Abstract: Aquaculture is the fastest growing food sector worldwide, mostly driven by a steadily increasing protein demand. In response to growing ecological concerns, life cycle assessment (LCA) emerged as a key environmental tool to measure the impacts of various production systems, including aquaculture. In this review, we focused on farmed salmonids to perform an in-depth analysis, investigating methodologies and comparing results of LCA studies of this finfish family in relation to species and production technologies. Identifying the environmental strengths and weaknesses of salmonid production technologies is central to ensure that industrial actors and policymakers make informed choices to take the production of this important marine livestock to a more sustainable path. Three critical aspects of salmonid LCAs were studied based on 24 articles and reports: (1) Methodological application, (2) construction of inventories, and (3) comparison of production technologies across studies. -

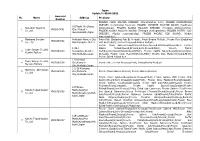

Japan Update to 05.04.2021 Approval No Name Address Products Number FROZEN CHUM SALMON DRESSED (Oncorhynchus Keta)

Japan Update to 05.04.2021 Approval No Name Address Products Number FROZEN CHUM SALMON DRESSED (Oncorhynchus keta). FROZEN DOLPHINFISH DRESSED (Coryphaena hippurus). FROZEN JAPANESE SARDINE ROUND (Sardinops 81,Misaki-Cho,Rausu- Kaneshin Tsuyama melanostictus). FROZEN ALASKA POLLACK DRESSED (Theragra chalcogramma). 1 VN01870001 Cho, Menashi- Co.,Ltd FROZEN ALASKA POLLACK ROUND (Theragra chalcogramma). FROZEN PACIFIC COD Gun,Hokkaido,Japan DRESSED. (Gadus macrocephalus). FROZEN PACIFIC COD ROUND. (Gadus macrocephalus) Maekawa Shouten Hokkaido Nemuro City Fresh Fish (Excluding Fish By-Product); Fresh Bivalve Mollusk.; Frozen Fish (Excluding 2 VN01860002 Co., Ltd Nishihamacho 10-177 Fish By-Product); Frozen Processed Bivalve Mollusk; Frozen Chum Salmon(Round,Dressed,Semi-Dressed,Fillet,Head,Bone,Skin); Frozen 1-35-1 Alaska Pollack(Round,Dressed,Semi-Dressed,Fillet); Frozen Pacific Taiyo Sangyo Co.,Ltd. 3 VN01840003 Showachuo,Kushiro- Cod(Round,Dressed,Semi-Dressed,Fillet); Frozen Pacific Saury(Round,Dressed,Semi- Kushiro Factory City,Hokkaido,Japan Dressed); Frozen Chub Mackerel(Round,Fillet); Frozen Blue Mackerel(Round,Fillet); Frozen Salted Pollack Roe 3-9 Komaba- Taiyo Sangyo Co.,Ltd. 4 VN01860004 Cho,Nemuro- Frozen Fish ; Frozen Processed Fish; (Excluding By-Product) Nemuro Factory City,Hokkaido,Japan 3-2-20 Kitahama- Marutoku Abe Suisan 5 VN01920005 Cho,Monbetu- Frozen Chum Salmon Dressed; Frozen Salmon Dressed Co.,Ltd City,Hokkaido,Japan Frozen Chum Salmon(Round,Semi-Dressed,Fillet); Frozen Salmon Milt; Frozen Pink Salmon(Round,Semi-Dressed,Dressed,Fillet); -

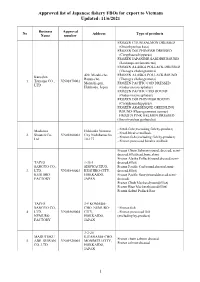

Approved List of Japanese Fishery Fbos for Export to Vietnam Updated: 11/6/2021

Approved list of Japanese fishery FBOs for export to Vietnam Updated: 11/6/2021 Business Approval No Address Type of products Name number FROZEN CHUM SALMON DRESSED (Oncorhynchus keta) FROZEN DOLPHINFISH DRESSED (Coryphaena hippurus) FROZEN JAPANESE SARDINE ROUND (Sardinops melanostictus) FROZEN ALASKA POLLACK DRESSED (Theragra chalcogramma) 420, Misaki-cho, FROZEN ALASKA POLLACK ROUND Kaneshin Rausu-cho, (Theragra chalcogramma) 1. Tsuyama CO., VN01870001 Menashi-gun, FROZEN PACIFIC COD DRESSED LTD Hokkaido, Japan (Gadus macrocephalus) FROZEN PACIFIC COD ROUND (Gadus macrocephalus) FROZEN DOLPHIN FISH ROUND (Coryphaena hippurus) FROZEN ARABESQUE GREENLING ROUND (Pleurogrammus azonus) FROZEN PINK SALMON DRESSED (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha) - Fresh fish (excluding fish by-product) Maekawa Hokkaido Nemuro - Fresh bivalve mollusk. 2. Shouten Co., VN01860002 City Nishihamacho - Frozen fish (excluding fish by-product) Ltd 10-177 - Frozen processed bivalve mollusk Frozen Chum Salmon (round, dressed, semi- dressed,fillet,head,bone,skin) Frozen Alaska Pollack(round,dressed,semi- TAIYO 1-35-1 dressed,fillet) SANGYO CO., SHOWACHUO, Frozen Pacific Cod(round,dressed,semi- 3. LTD. VN01840003 KUSHIRO-CITY, dressed,fillet) KUSHIRO HOKKAIDO, Frozen Pacific Saury(round,dressed,semi- FACTORY JAPAN dressed) Frozen Chub Mackerel(round,fillet) Frozen Blue Mackerel(round,fillet) Frozen Salted Pollack Roe TAIYO 3-9 KOMABA- SANGYO CO., CHO, NEMURO- - Frozen fish 4. LTD. VN01860004 CITY, - Frozen processed fish NEMURO HOKKAIDO, (excluding by-product) FACTORY JAPAN