07 Trites FB105(2)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edna Assay Development

Environmental DNA assays available for species detection via qPCR analysis at the U.S.D.A Forest Service National Genomics Center for Wildlife and Fish Conservation (NGC). Asterisks indicate the assay was designed at the NGC. This list was last updated in June 2021 and is subject to change. Please contact [email protected] with questions. Family Species Common name Ready for use? Mustelidae Martes americana, Martes caurina American and Pacific marten* Y Castoridae Castor canadensis American beaver Y Ranidae Lithobates catesbeianus American bullfrog Y Cinclidae Cinclus mexicanus American dipper* N Anguillidae Anguilla rostrata American eel Y Soricidae Sorex palustris American water shrew* N Salmonidae Oncorhynchus clarkii ssp Any cutthroat trout* N Petromyzontidae Lampetra spp. Any Lampetra* Y Salmonidae Salmonidae Any salmonid* Y Cottidae Cottidae Any sculpin* Y Salmonidae Thymallus arcticus Arctic grayling* Y Cyrenidae Corbicula fluminea Asian clam* N Salmonidae Salmo salar Atlantic Salmon Y Lymnaeidae Radix auricularia Big-eared radix* N Cyprinidae Mylopharyngodon piceus Black carp N Ictaluridae Ameiurus melas Black Bullhead* N Catostomidae Cycleptus elongatus Blue Sucker* N Cichlidae Oreochromis aureus Blue tilapia* N Catostomidae Catostomus discobolus Bluehead sucker* N Catostomidae Catostomus virescens Bluehead sucker* Y Felidae Lynx rufus Bobcat* Y Hylidae Pseudocris maculata Boreal chorus frog N Hydrocharitaceae Egeria densa Brazilian elodea N Salmonidae Salvelinus fontinalis Brook trout* Y Colubridae Boiga irregularis Brown tree snake* -

Marine Fish Culture

FAU Institutional Repository http://purl.fcla.edu/fau/fauir This paper was submitted by the faculty of FAU’s Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute. Notice: © 1998 Kluwer. This manuscript is an author version with the final publication available and may be cited as: Tucker, J. W., Jr. (1998). Marine fish culture. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers. MARINE FISH CULTURE by John W. Tucker, Jr., Ph.D. Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institution and Florida Institute of Technology, Melbourne KLUWER ACADEMIC PUBLISHERS Boston I Dordrecht I London Distributors for North, Central and South America: Kluwer Academic Publishers I 01 Philip Drive Assinippi Park Norwell, Massachusetts 02061 USA Telephone (781) 871-6600 Fax (781) 871-6528 E-Mail <[email protected]> Distributors for all other countries: Kluwer Academic Publishers Group Distribution Centre Post Office Box 322 3300 AH Dordrecht, THE NETHERLANDS Telephone 31 78 6392 392 Fax 31 78 6546 474 E-Mail <[email protected]> '' Electronic Services <http://www.wkap.nl> Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Tucker, John W., 1948- Marine fish culture I by John W. Tucker, Jr. p. em. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 0-412-07151-7 (alk. paper) 1. Marine fishes. 2. Fish-culture. I. Title. SH163.T835 1998 639.3'2--dc21 98-42062 CIP Copyright © 1998 by Kluwer Academic Publishers All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, photo copying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher, Kluwer Academic Publishers, I 0 I Philip Drive, Assinippi Park, Norwell, Massachusetts 02061 Printed on acid-free paper. -

Lake Tahoe Fish Species

Description: o The Lohonton cutfhroot trout (LCT) is o member of the Solmonidqe {trout ond solmon) fomily, ond is thought to be omong the most endongered western solmonids. o The Lohonton cufihroot wos listed os endongered in 1970 ond reclossified os threotened in 1975. Dork olive bdcks ond reddish to yellow sides frequently chorocterize the LCT found in streoms. Steom dwellers reoch l0 inches in length ond only weigh obout I lb. Their life spon is less thon 5 yeors. ln streoms they ore opportunistic feeders, with diets consisting of drift orgonisms, typicolly terrestriol ond oquotic insects. The sides of loke-dwelling LCT ore often silvery. A brood, pinkish stripe moy be present. Historicolly loke dwellers reoched up to 50 inches in length ond weigh up to 40 pounds. Their life spon is 5-14yeors. ln lokes, smoll Lohontons feed on insects ond zooplonkton while lorger Lohonions feed on other fish. Body spots ore the diognostic chorocter thot distinguishes the Lohonion subspecies from the .l00 Poiute cutthroot. LCT typicolly hove 50 to or more lorge, roundish-block spots thot cover their entire bodies ond their bodies ore typicolly elongoted. o Like other cufihroot trout, they hove bosibronchiol teeth (on the bose of tongue), ond red sloshes under their iow (hence the nome "cutthroot"). o Femole sexuol moturity is reoch between oges of 3 ond 4, while moles moture ot 2 or 3 yeors of oge. o Generolly, they occur in cool flowing woier with ovoiloble cover of well-vegetoted ond stoble streom bonks, in oreos where there ore streom velocity breoks, ond in relotively silt free, rocky riffle-run oreos. -

Summary Report of Freshwater Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S

Summary Report of Freshwater Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 4—An Update April 2013 Prepared by: Pam L. Fuller, Amy J. Benson, and Matthew J. Cannister U.S. Geological Survey Southeast Ecological Science Center Gainesville, Florida Prepared for: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Atlanta, Georgia Cover Photos: Silver Carp, Hypophthalmichthys molitrix – Auburn University Giant Applesnail, Pomacea maculata – David Knott Straightedge Crayfish, Procambarus hayi – U.S. Forest Service i Table of Contents Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................................... ii List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................ v List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................ vi INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 1 Overview of Region 4 Introductions Since 2000 ....................................................................................... 1 Format of Species Accounts ...................................................................................................................... 2 Explanation of Maps ................................................................................................................................ -

Inland Fishes of California

Inland Fishes of California Revise d and Expanded PETER B. MO YL E Illustrations by Chris Ma ri van Dyck and Joe Tome ller i NIVERS ITyor ALfFORNJA PRESS Ikrkd cr I.", ..\ n~d e ' Lon don Universit }, 0 Ca lifornia Press Herkdey and Los Angeles, Ca lifornia Uni ve rsity of alifornia Press, Ltd. Lundun, England ~ 2002 by the Regents of the Unive rsi ty of Ca lifornia Library of Cungress ataloging-in -Publ ica tion Data j\·[oyk, Pen: r B. Inland fis hes of California / Peter B. Moyle ; illustrations by Chris Mari van D)'ck and Joe Tomell eri.- Rev. and expanded. p. cm. In lu de> bibl iographical refe rences (p. ). ISBN 0- 20-2.2754 -'1 (cl ot h: alk. papa) I. rreshw:ltcr lishes-Cali(ornia. I. Title. QL62S C2 M6H 2002 597 .17/i'097Q4-dc21 20010 27680 1\!UlIl.Ifaclu rcd in Canacla II 10 Q9 00 07 06 0 04 03 02 10 ' 1\ 7 b '; -\ 3 2 1 Th paper u!)ed in thi> public.ltiu(] 111l'd., the minimum requirements "fA SI / i': ISO Z39.4H-1992 (R 199;) ( Pmlllllh'/l e ofPa pcr) . e Special Thanks The illustrations for this book were made possible by gra nts from the following : California-Nevada Chapter, American Fi she ries Soc iety Western Di vision, Am erican Fi she ries Society California Department of Fish and Game Giles W. and El ise G. Mead Foundation We appreciate the generous funding support toward the publication of this book by the United Sta tes Environme ntal Protection Agency, Region IX, San Francisco Contents Pre(acc ix Salmon and Trout, Salmonidae 242 Ackl10 11'ledgl11 el1ts Xlll Silversides, Atherinopsidae 307 COlll'er,<iol1 ['actors xv -

Comparing Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Salmonid Aquaculture Production Systems: Status and Perspectives

sustainability Review Comparing Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Salmonid Aquaculture Production Systems: Status and Perspectives Gaspard Philis 1,* , Friederike Ziegler 2 , Lars Christian Gansel 1, Mona Dverdal Jansen 3 , Erik Olav Gracey 4 and Anne Stene 1 1 Department of Biological Sciences, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Larsgårdsvegen 2, 6009 Ålesund, Norway; [email protected] (L.C.G.); [email protected] (A.S.) 2 Agrifood and Bioscience, RISE Research Institutes of Sweden, Post box 5401, 40229 Gothenburg, Sweden; [email protected] 3 Section for Epidemiology, Norwegian Veterinary Institute, Pb 750 Sentrum, 0106 Oslo, Norway; [email protected] 4 Sustainability Department, BioMar Group, Havnegata 9, 7010 Trondheim, Norway; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +47-451-87-634 Received: 31 March 2019; Accepted: 27 April 2019; Published: 30 April 2019 Abstract: Aquaculture is the fastest growing food sector worldwide, mostly driven by a steadily increasing protein demand. In response to growing ecological concerns, life cycle assessment (LCA) emerged as a key environmental tool to measure the impacts of various production systems, including aquaculture. In this review, we focused on farmed salmonids to perform an in-depth analysis, investigating methodologies and comparing results of LCA studies of this finfish family in relation to species and production technologies. Identifying the environmental strengths and weaknesses of salmonid production technologies is central to ensure that industrial actors and policymakers make informed choices to take the production of this important marine livestock to a more sustainable path. Three critical aspects of salmonid LCAs were studied based on 24 articles and reports: (1) Methodological application, (2) construction of inventories, and (3) comparison of production technologies across studies. -

An Estimation of Potential Salmonid Habitat Capacity in the Upper Mainstem Eel River, California

AN ESTIMATION OF POTENTIAL SALMONID HABITAT CAPACITY IN THE UPPER MAINSTEM EEL RIVER, CALIFORNIA By Emily Jeanne Cooper A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Humboldt State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Natural Resources: Environmental and Natural Resource Science Committee Membership Dr. Alison O’Dowd, Committee Chair Dr. James Graham, Committee Member Dr. Darren Ward, Committee Member Dr. Alison O’Dowd, Graduate Coordinator May 2017 ABSTRACT AN ESTIMATION OF POTENTIAL SALMONID HABITAT CAPACITY IN THE UPPER MAINSTEM EEL RIVER, CALIFORNIA Emily Jeanne Cooper In Northern California’s Eel River watershed, the two dams that make up the Potter Valley Project (PVP) restrict the distribution and production of anadromous salmonids, and current populations of Chinook Salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) and steelhead trout (O. mykiss) in the upper mainstem Eel River are in need of recovery. In anticipation of the upcoming FERC relicensing of the PVP, this project provides an estimation of the extent of potential salmonid habitat and its capacity for steelhead trout and Chinook Salmon in the upper mainstem Eel River watershed above the impassable Scott Dam. Using three fish passage scenarios, potential Chinook Salmon habitat was estimated between 89-127 km (55-79 mi) for spawning and rearing; potential steelhead trout habitat was estimated between 318-463 km (198-288 mi) for spawning and between 179-291 km (111-181 mi) for rearing. Rearing habitat capacity was modeled with the Unit Characteristic Method, which used surrogate fish density values specific to habitat units (i.e. pools, riffles, runs) that were adjusted by measured habitat conditions. -

History of Fishes - Structural Patterns and Trends in Diversification

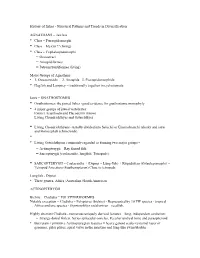

History of fishes - Structural Patterns and Trends in Diversification AGNATHANS = Jawless • Class – Pteraspidomorphi • Class – Myxini?? (living) • Class – Cephalaspidomorphi – Osteostraci – Anaspidiformes – Petromyzontiformes (living) Major Groups of Agnathans • 1. Osteostracida 2. Anaspida 3. Pteraspidomorphida • Hagfish and Lamprey = traditionally together in cyclostomata Jaws = GNATHOSTOMES • Gnathostomes: the jawed fishes -good evidence for gnathostome monophyly. • 4 major groups of jawed vertebrates: Extinct Acanthodii and Placodermi (know) Living Chondrichthyes and Osteichthyes • Living Chondrichthyans - usually divided into Selachii or Elasmobranchi (sharks and rays) and Holocephali (chimeroids). • • Living Osteichthyans commonly regarded as forming two major groups ‑ – Actinopterygii – Ray finned fish – Sarcopterygii (coelacanths, lungfish, Tetrapods). • SARCOPTERYGII = Coelacanths + (Dipnoi = Lung-fish) + Rhipidistian (Osteolepimorphi) = Tetrapod Ancestors (Eusthenopteron) Close to tetrapods Lungfish - Dipnoi • Three genera, Africa+Australian+South American ACTINOPTERYGII Bichirs – Cladistia = POLYPTERIFORMES Notable exception = Cladistia – Polypterus (bichirs) - Represented by 10 FW species - tropical Africa and one species - Erpetoichthys calabaricus – reedfish. Highly aberrant Cladistia - numerous uniquely derived features – long, independent evolution: – Strange dorsal finlets, Series spiracular ossicles, Peculiar urohyal bone and parasphenoid • But retain # primitive Actinopterygian features = heavy ganoid scales (external -

![Kyfishid[1].Pdf](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2624/kyfishid-1-pdf-1462624.webp)

Kyfishid[1].Pdf

Kentucky Fishes Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources Kentucky Fish & Wildlife’s Mission To conserve, protect and enhance Kentucky’s fish and wildlife resources and provide outstanding opportunities for hunting, fishing, trapping, boating, shooting sports, wildlife viewing, and related activities. Federal Aid Project funded by your purchase of fishing equipment and motor boat fuels Kentucky Department of Fish & Wildlife Resources #1 Sportsman’s Lane, Frankfort, KY 40601 1-800-858-1549 • fw.ky.gov Kentucky Fish & Wildlife’s Mission Kentucky Fishes by Matthew R. Thomas Fisheries Program Coordinator 2011 (Third edition, 2021) Kentucky Department of Fish & Wildlife Resources Division of Fisheries Cover paintings by Rick Hill • Publication design by Adrienne Yancy Preface entucky is home to a total of 245 native fish species with an additional 24 that have been introduced either intentionally (i.e., for sport) or accidentally. Within Kthe United States, Kentucky’s native freshwater fish diversity is exceeded only by Alabama and Tennessee. This high diversity of native fishes corresponds to an abun- dance of water bodies and wide variety of aquatic habitats across the state – from swift upland streams to large sluggish rivers, oxbow lakes, and wetlands. Approximately 25 species are most frequently caught by anglers either for sport or food. Many of these species occur in streams and rivers statewide, while several are routinely stocked in public and private water bodies across the state, especially ponds and reservoirs. The largest proportion of Kentucky’s fish fauna (80%) includes darters, minnows, suckers, madtoms, smaller sunfishes, and other groups (e.g., lam- preys) that are rarely seen by most people. -

Family - Salmonidae

Family - Salmonidae Salmonid fishes include some of world's most important freshwater angling and aquaculture species. This family is native to the cool and cold waters of the Northern Hemisphere. Salmonids were first introduced to Australia in the nineteenth century, and were some of the first introductions for this family. This family is characterised by small scales, a lateral line, dorsal fin high on the back, forward on the pelvics. Closely related to the native families Aplochitonidae, Galaxiidae, Protoroctidae, and Retropinnidae. Brown trout Salmo trutta Linnaeus (R.M. McDowall) Other names: Sea trout, Englishman. Description: A thick-bodied and shallow species with a big head and mouth. Mouth becoming increasingly large with growth, and eyes relatively smaller. Dorsal fin (12-14 rays); pectoral rays (13-14); adipose fin well developed. Caudal peduncle relatively deep, and tail forked slightly or not at all. Distinct lateral line. Vertebrae 56-61. Distribution: Established in high altitude, cooler waters mostly in the highlands above 600 m. Throughout New South Wales, The Australian Capital Territory, and Victoria, including the headwaters of the Murry-Darling, and Tasmania. In Tasmania it is widespread and abundant down to sea level in all major drainages with exception to the Davey River and Bathurst harbour streams. Stocked populations are maintained in the warmer waters of New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania, South Australia (Adelaide region) and south of Perth inWestern Australia. Natural History: Is a native species to Europe, from Iceland and Scandinavia south to Spain and northern Africa, and eastward to the Black and Caspian Seas. Introduced to Australian waters in Alien Fishes | Family Salmonidae | Page 1 the 1860s as an angling species. -

Oncorhynchus Mykiss) (Salmoniformes: Salmonidae) Diet in Hawaiian Streams1

Pacific Science (1999), vol. 53, no. 3: 242-251 © 1999 by University of Hawai'i Press. All rights reserved Alien Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) (Salmoniformes: Salmonidae) Diet in Hawaiian Streams1 MICHAEL H. KIDO,2 DONALD E. HEACOCK,3 AND ADAM ASQUITH4 ABSTRACT: Diet of rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss (Walbaum), intro duced by the State of Hawai'i into tropical headwater streams of the Waimea River in the Koke'e area ofthe Hawaiian island ofKaua'i, was examined in this study through gut content analysis. In Wai'alae Stream, rainbow trout were found to be opportunistic general predators efficient at feeding on invertebrate drift. Foods eaten ranged from juvenile trout, to terrestrial and aquatic arthro pods, to algae and aquatic mosses. Native aquatic species, particularly dragonfly (Anax strennus) and damselfly (Megalagrion heterogamias) naiads, lyrnnaeid snails (Erinna aulacospira), and atyid shrimp (Atyoida bisulcata), were deter mined to be major foods for alien trout. Terrestrial invertebrates (primarily ar thropods), however, provided a substantial (albeit unpredictable) additional food supply. Based on results of the study, it is cautioned that large numbers of rainbow trout indiscriminantly released into lower- to middle-elevation reaches ofHawaiian streams could do substantial damage to populations ofna tive aquatic species through predation, competition, and/or habitat alteration. RAINBOW TROUT, Oncorhynchus mykiss the high-elevation (ca. 3500 ft [1067 m]) Ko (Walbaum), along with several other Salmo ke'e area of Kaua'i Island (Figure I) (Need niformes (Salmonidae), were introduced into ham and Welsh 1953). By 1941, only Koke'e Hawaiian Island streams early in the century streams were being stocked. -

Case 3526 Salmo Formosanus Jordan & Oshima, 1919 (Currently

300 Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature 67(4) December 2010 Case 3526 Salmo formosanus Jordan & Oshima, 1919 (currently Oncorhynchus formosanus) (Pisces, SALMONIDAE, SALMONINAE): proposed conservation of the specific name Hsuan-Ching Ho Biodiversity Research Center, Academia Sinica, No. 128, Sec. 2, Academia Rd., Nankang, Taipei, 115 Taiwan & National Museum of Marine Biology & Aquarium, No. 2, Houwan Rd., Pingtung, 944 Taiwan (e-mail: [email protected]) Jin-Chywan Gwo Department of Aquaculture, Taiwan National Ocean University, No. 2, Peining Rd., Keelung, 202 Taiwan (e-mail: [email protected]) Abstract. The purpose of this application, under Article 23.9.3 of the Code, is to conserve the specific name Salmo formosanus Jordan & Oshima, 1919 (currently Oncorhynchus formosanus) for an endemic landlocked salmon in Taiwan. The older name Salmo saramao Jordan & Oshima in Oshima, 1919 is a senior subjective synonym of S. formosanus, but has not been catalogued or used since it was described. The suppression of S. saramao is therefore proposed to conserve the name S. formosanus. Keywords. Nomenclature; taxonomy; SALMONIDAE; Oncorhynchus formosanus; Onco- rhynchus saramao; salmon; Taiwan. 1. On 18 October 1917, Takeo Aoki received a freshwater salmon specimen (33.9 cm TL, preserved with salt) from Saramao [Lishan], upstream of Taiko River [Tachia R.], Taiwan. He reported this finding and gave a detailed description for the specimen (Aoki, 1917a, b, c). However, no scientific name was provided. 2. Jordan & Oshima in Oshima (June 1919, p. 14) described Salmo saramao based on two specimens [syntypes], the mature salt-preserved specimen received by Takeo Aoki and a juvenile (14.8 cm TL, SU 23054) raised at Saramao police station in Musha (or Musya, Wushe), Taiwan.