University of Cincinnati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Illyrian Religion and Nation As Zero Institution

Studies in Visual Arts and Communication: an international journal Vol 3, No 1 (2016) on-line ISSN 2393 - 1221 Illyrian religion and nation as zero institution Josipa Lulić * Abstract The main theoretical and philosophical framework for this paper are Louis Althusser's writings on ideology, and ideological state apparatuses, as well as Rastko Močnik’s writings on ideology and on the nation as the zero institution. This theoretical framework is crucial for deconstructing some basic tenants in writing on the religious sculpture in Roman Dalmatia, and the implicit theoretical constructs that govern the possibilities of thought on this particular subject. This paper demonstrates how the ideological construct of nation that ensures the reproduction of relations of production of modern societies is often implicitly or explicitly projected into the past, as trans-historical construct, thus soliciting anachronistic interpretations of the material remains of past societies. This paper uses the interpretation of religious sculpture in Roman Dalmatia as a case study to stress the importance of the critique of ideology in the art history. The religious sculpture in Roman Dalmatia has been researched almost exclusively through the search for the presumed elements of Illyrian religion in visual representations; the formulation of the research hypothesis was firmly rooted into the idea of nation as zero institution, which served as the default framework for various interpretations. In this paper I try to offer some alternative interpretations, intending not to give definite answers, but to open new spaces for research. Keywords: Roman sculpture, province of Dalmatia, nation as zero institution, ideology, Rastko Močnik, Louis Althusser. -

Alexander the Great, in Case That, Having Completed the Conquest of Asia, He Should Have Turned His Arms on Europe

Alexander the Great, in case that, having completed the conquest of Asia, he should have turned his arms on Europe. 17 Nothing can be found farther from my intention, since the commencement of this history, than to digress, more than necessity required, from the course of narration; and, by embellishing my work with variety, to seek pleasing resting-places, as it were, for my readers, and relaxation for my own mind: nevertheless, the mention of so great a king and commander, now calls forth to public view those silent reflections, whom Alexander must have fought. Manlius Torquatus, had he met him in the field, might, perhaps, have yielded to Alexander in discharging military duties in battle (for these also render him no less illustrious); and so might Valerius Corvus; men who were distinguished soldiers, before they became commanders. The same, too, might have been the case with the Decii, who, after devoting their persons, rushed upon the enemy; or of Papirius Cursor, though possessed of such powers, both of body and mind. By the counsels of one youth, it is possible the wisdom of a whole senate, not to mention individuals, might have been baffled, [consisting of such members,] that he alone, who declared that "it consisted of kings," conceived a correct idea of a Roman senate. But then the danger was, that with more judgment than any one of those whom I have named he might choose ground for an encampment, provide supplies, guard against stratagems, distinguish the season for fighting, form his line of battle, or strengthen it properly with reserves. -

The Fleet of Syracuse (480-413 BCE)

ANDREAS MORAKIS The Fleet of Syracuse (480-413 BCE) The Deinomenids The ancient sources make no reference to the fleet of Syracuse until the be- ginning of the 5th century BCE. In particular, Thucydides, when considering the Greek maritime powers at the time of the rise of the Athenian empire, includes among them the tyrants of Sicily1. Other sources refer more precisely to Gelon’s fleet, during the Carthaginian invasion in Sicily. Herodotus, when the Greeks en- voys asked for Gelon’s help to face Xerxes’ attack, mentions the lord of Syracuse promising to provide, amongst other things, 200 triremes in return of the com- mand of the Greek forces2. The same number of ships is also mentioned by Ti- maeus3 and Ephorus4. It is very odd, though, that we hear nothing of this fleet during the Carthaginian campaign and the Battle of Himera in either the narration of Diodorus, or the briefer one of Herodotus5. Nevertheless, other sources imply some kind of naval fighting in Himera. Pausanias saw offerings from Gelon and the Syracusans taken from the Phoenicians in either a sea or a land battle6. In addition, the Scholiast to the first Pythian of Pindar, in two different situations – the second one being from Ephorus – says that Gelon destroyed the Carthaginians in a sea battle when they attacked Sicily7. 1 Thuc. I 14, 2: ὀλίγον τε πρὸ τῶν Μηδικῶν καὶ τοῦ ∆αρείου θανάτου … τριήρεις περί τε Σικελίαν τοῖς τυράννοις ἐς πλῆθος ἐγένοντο καὶ Κερκυραίοις. 2 Hdt. VII 158. 3 Timae. FGrHist 566 F94= Polyb. XII 26b, 1-5, but the set is not the court of Gelon, but the conference of the mainland Greeks in Corinth. -

The First Illyrian War: a Study in Roman Imperialism

The First Illyrian War: A Study in Roman Imperialism Catherine A. McPherson Department of History and Classical Studies McGill University, Montreal February, 2012 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts ©Catherine A. McPherson, 2012. Table of Contents Abstract ……………………………………………….……………............2 Abrégé……………………………………...………….……………………3 Acknowledgements………………………………….……………………...4 Introduction…………………………………………………………………5 Chapter One Sources and Approaches………………………………….………………...9 Chapter Two Illyria and the Illyrians ……………………………………………………25 Chapter Three North-Western Greece in the Later Third Century………………………..41 Chapter Four Rome and the Outbreak of War…………………………………..……….51 Chapter Five The Conclusion of the First Illyrian War……………….…………………77 Conclusion …………………………………………………...…….……102 Bibliography……………………………………………………………..104 2 Abstract This paper presents a detailed case study in early Roman imperialism in the Greek East: the First Illyrian War (229/8 B.C.), Rome’s first military engagement across the Adriatic. It places Roman decision-making and action within its proper context by emphasizing the role that Greek polities and Illyrian tribes played in both the outbreak and conclusion of the war. It argues that the primary motivation behind the Roman decision to declare war against the Ardiaei in 229 was to secure the very profitable trade routes linking Brundisium to the eastern shore of the Adriatic. It was in fact the failure of the major Greek powers to limit Ardiaean piracy that led directly to Roman intervention. In the earliest phase of trans-Adriatic engagement Rome was essentially uninterested in expansion or establishing a formal hegemony in the Greek East and maintained only very loose ties to the polities of the eastern Adriatic coast. -

The Sweep of History

STUDENT’S World History & Geography 1 1 1 Essentials of World History to 1500 Ver. 3.1.10 – Rev. 2/1/2011 WHG1 The following pages describe significant people, places, events, and concepts in the story of humankind. This information forms the core of our study; it will be fleshed-out by classroom discussions, audio-visual mat erials, readings, writings, and other act ivit ies. This knowledge will help you understand how the world works and how humans behave. It will help you understand many of the books, news reports, films, articles, and events you will encounter throughout the rest of your life. The Student’s Friend World History & Geography 1 Essentials of world history to 1500 History What is history? History is the story of human experience. Why study history? History shows us how the world works and how humans behave. History helps us make judgments about current and future events. History affects our lives every day. History is a fascinating story of human treachery and achievement. Geography What is geography? Geography is the study of interaction between humans and the environment. Why study geography? Geography is a major factor affecting human development. Humans are a major factor affecting our natural environment. Geography affects our lives every day. Geography helps us better understand the peoples of the world. CONTENTS: Overview of history Page 1 Some basic concepts Page 2 Unit 1 - Origins of the Earth and Humans Page 3 Unit 2 - Civilization Arises in Mesopotamia & Egypt Page 5 Unit 3 - Civilization Spreads East to India & China Page 9 Unit 4 - Civilization Spreads West to Greece & Rome Page 13 Unit 5 - Early Middle Ages: 500 to 1000 AD Page 17 Unit 6 - Late Middle Ages: 1000 to 1500 AD Page 21 Copyright © 1998-2011 Michael G. -

Keltoi and Hellenes: a Study of the Celts in the Hellenistic World

KELTOI AND THE HELLENES A STUDY OF THE CELTS IN THE HELLENISTIC WoRU) PATRICK EGAN In the third century B.C. a large body ofCeltic tribes thrust themselves violently into the turbulent world of the Diadochoi,’ immediately instilling fear, engendering anger and finally, commanding respect from the peoples with whom they came into contact. Their warlike nature, extreme hubris and vigorous energy resembled Greece’s own Homeric past, but represented a culture, language and way of life totally alien to that of the Greeks and Macedonians in this period. In the years that followed, the Celts would go on to ravage Macedonia, sack Delphi, settle their own “kingdom” and ifil the ranks of the Successors’ armies. They would leave indelible marks on the Hellenistic World, first as plundering barbaroi and finally, as adapted, integral elements and members ofthe greatermulti-ethnic society that was taking shape around them. This paper will explore the roles played by the Celts by examining their infamous incursions into Macedonia and Greece, their phase of settlement and occupation ofwhat was to be called Galatia, their role as mercenaries, and finally their transition and adaptation, most noticeably on the individual level, to the demands of the world around them. This paper will also seek to challenge some of the traditionally hostile views held by Greek historians regarding the role, achievements, and the place the Celts occupied as members, not simply predators, of the Hellenistic World.2 19 THE DAWN OF THE CELTS IN THE HELLENISTIC WORLD The Celts were not unknown to all Greeks in the years preceding the Deiphic incursion of February, 279. -

00010853-Preview.Pdf

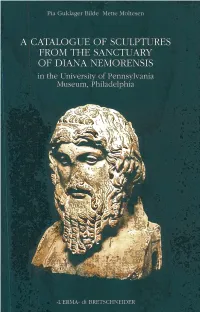

ANALECTA ROMANA INSTITUTI DANIcI Supplemen turn XXIX A CATALOGUE OF SCULPTURES FROM THE SANCTUARY OF DIANA NEMORENSIS IN THE UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA MUSEUM, PHILADELPHIA A Catalogue of Sculptures from the Sanctuary of Diana Nemorensis in The University of Pennsylvania Museum, Philadelphia by Pia Guldager Bilde and Mette Moltesen <<L'ERMA>> di BRETSCHNEIDER ROMAE MMII ANALECTA ROMANA INSTITUTI DANIcI, SUPPL. XXIX Accademia di Danimarca - Via Omero, 18 - 00197 Rome - Italy Lay-out by the editors © 2002 <<L'ERMA>> di BRETSCHNEIDER, Rome PUBLISHED WITH THE SUPPORT OF GRANTS FROM Knud Højgaards Fond Novo Nordisk Fonden University of Pennsylvania. Museum of archaeology and anthropology A catalogue of sculptures from the sanctuary of Diana Nemorensis in the University of Pennsylvania Museum, Philadelphia / by Pia Guldager Bilde and Mette Moltesen. - Roma: <<L'ERMA>> di BRETSCHNEIDER , 2002. - 95 p. : ill. ; 30 cm. (Analecta Romana Instituti Danici. Supplementum ; 29) ISBN 88-8265-211-4 CDD 21. 731.4 1. Sculture in marmo - Collezioni 2. Filadelfia - University of Pennsylvania - Museum of archaeology and anthropology - Cataloghi I. Guldager Bilde, Pia II. Moltesen, Mette The journal ANALECTA ROMANA INSTITUTI DANICI (ARID) publishes studies within the main range of the Academy's research activities: the arts and humanities, history and archaeology. Intending contributors should get in touch with the editors, who will supply a set of guide- lines and establish a deadline. A print of the article, accompanied y a disk containing the text should be sent to the editors, Accademia di Danimarca, 18 Via Omero, I - 00197 Roma, tel. +39 06 32 65 931, fax +39 06 32 22 717. -

The Burial of the Urban Poor in Italy in the Late Republic and Early Empire

Death, disposal and the destitute: The burial of the urban poor in Italy in the late Republic and early Empire Emma-Jayne Graham Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Archaeology University of Sheffield December 2004 IMAGING SERVICES NORTH Boston Spa, Wetherby West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ www.bl.uk The following have been excluded from this digital copy at the request of the university: Fig 12 on page 24 Fig 16 on page 61 Fig 24 on page 162 Fig 25 on page 163 Fig 26 on page 164 Fig 28 on page 168 Fig 30on page 170 Fig 31 on page 173 Abstract Recent studies of Roman funerary practices have demonstrated that these activities were a vital component of urban social and religious processes. These investigations have, however, largely privileged the importance of these activities to the upper levels of society. Attempts to examine the responses of the lower classes to death, and its consequent demands for disposal and commemoration, have focused on the activities of freedmen and slaves anxious to establish or maintain their social position. The free poor, living on the edge of subsistence, are often disregarded and believed to have been unceremoniously discarded within anonymous mass graves (puticuli) such as those discovered at Rome by Lanciani in the late nineteenth century. This thesis re-examines the archaeological and historical evidence for the funerary practices of the urban poor in Italy within their appropriate social, legal and religious context. The thesis attempts to demonstrate that the desire for commemoration and the need to provide legitimate burial were strong at all social levels and linked to several factors common to all social strata. -

Sommario Abbreviazioni

SOMMARIO Pag . ABBREVIAZIONI.......................................... vi1 INTRODUZIONE........................................... 1 Capitolo I .LA CAVITA RUPESTRE COME LUOGO DI CULTO : IMMAGINARIO E REALTA ............................... 11 1. L’eredità simbolica della grotta ........................ 11 Gregorio di Nissa. p . 12; il reliquiano del Suncru Sunctomm e l’ampolla di Monza. p . 13; grotte e locu sunctu della Palestina. p . 15; dalla Terrasanta all’occidente. p . 17; l’eredità del paga- nesimo. p . 19; san Silvestro e il drago. p . 22; il ruolo del vesco- vo. p . 24. 2 . Escavazioni artificiali e grotte naturali ................. 25 Escavazioni nel tufo. p . 32; grotte carsiche. p . 34; tipologie semirupestri. p . 36; sacralità e funzionalità. p . 37 . Capitolo I1 .CATALOGO DELLE TESTIMONIANZE PITTORICHE 39 1. Provincia di Viterbo .................................. 39 Barbarano Romano. Grotta di San Simone ................ 39 Bassano Romano. San Giovanni a Pollo ................... 40 Bolsena. «Grotta» di Santa Cristina ....................... 43 Caste1 Sant’Elia. Grotta di San Leonard0 .................. 47 Civita Castellana. Grotte di San Cesareo ................... 52 Civita Castellana. Grotte di San Selmo .................... 54 Ischia di Castro. Eremo di Poggio del Conte ............... 56 Norchia. Grotta di San Vivenzio .......................... 57 Sutri. Chiesa rupestre di Santa Fortunata .................. 61 Sutri. Santuario di Santa Maria del Parto .................. 63 Vallerano. Grotta del Salvatore .......................... -

Map 44 Latium-Campania Compiled by N

Map 44 Latium-Campania Compiled by N. Purcell, 1997 Introduction The landscape of central Italy has not been intrinsically stable. The steep slopes of the mountains have been deforested–several times in many cases–with consequent erosion; frane or avalanches remove large tracts of regolith, and doubly obliterate the archaeological record. In the valley-bottoms active streams have deposited and eroded successive layers of fill, sealing and destroying the evidence of settlement in many relatively favored niches. The more extensive lowlands have also seen substantial depositions of alluvial and colluvial material; the coasts have been exposed to erosion, aggradation and occasional tectonic deformation, or–spectacularly in the Bay of Naples– alternating collapse and re-elevation (“bradyseism”) at a staggeringly rapid pace. Earthquakes everywhere have accelerated the rate of change; vulcanicity in Campania has several times transformed substantial tracts of landscape beyond recognition–and reconstruction (thus no attempt is made here to re-create the contours of any of the sometimes very different forerunners of today’s Mt. Vesuvius). To this instability must be added the effect of intensive and continuous intervention by humanity. Episodes of depopulation in the Italian peninsula have arguably been neither prolonged nor pronounced within the timespan of the map and beyond. Even so, over the centuries the settlement pattern has been more than usually mutable, which has tended to obscure or damage the archaeological record. More archaeological evidence has emerged as modern urbanization spreads; but even more has been destroyed. What is available to the historical cartographer varies in quality from area to area in surprising ways. -

Ancient Greek Society by Mark Cartwright Published on 15 May 2018

Ancient Greek Society by Mark Cartwright published on 15 May 2018 Although ancient Greek Society was dominated by the male citizen, with his full legal status, right to vote, hold public oce, and own property, the social groups which made up the population of a typical Greek city-state or polis were remarkably diverse. Women, children, immigrants (both Greek and foreign), labourers, and slaves all had dened roles, but there was interaction (oen illicit) between the classes and there was also some movement between social groups, particularly for second-generation ospring and during times of stress such as wars. The society of ancient Greece was largely composed of the following groups: male citizens - three groups: landed aristocrats (aristoi), poorer farmers (periokoi) and the middle class (artisans and traders). semi-free labourers (e.g the helots of Sparta). women - belonging to all of the above male groups but without citizen rights. children - categorised as below 18 years generally. slaves - the douloi who had civil or military duties. foreigners - non-residents (xenoi) or foreign residents (metoikoi) who were below male citizens in status. Classes Although the male citizen had by far the best position in Greek society, there were dierent classes within this group. Top of the social tree were the ‘best people’, the aristoi. Possessing more money than everyone else, this class could provide themselves with armour, weapons, and a horse when on military campaign. The aristocrats were oen split into powerful family factions or clans who controlled all of the important political positions in the polis. Their wealth came from having property and even more importantly, the best land, i.e.: the most fertile and the closest to the protection oered by the city walls. -

Etruscan Biophilia Viewed Through Magical Amber

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) Spring 5-9-2020 Etruscan Biophilia Viewed through Magical Amber Greta Rose Koshenina University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons, and the Other Classics Commons Recommended Citation Koshenina, Greta Rose, "Etruscan Biophilia Viewed through Magical Amber" (2020). Honors Theses. 1432. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/1432 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ETRUSCAN BIOPHILIA VIEWED THROUGH MAGICAL AMBER by Greta Rose Koshenina A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford May 2020 Approved by ___________________________________ Advisor: Dr. Jacqueline DiBiasie-Sammons ___________________________________ Reader: Dr. Molly Pasco-Pranger ___________________________________ Reader: Dr. John Samonds © 2020 Greta Rose Koshenina ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii DEDICATION I dedicate this thesis with gratitude to my advisors in both America and Italy: to Dr. Jacqueline DiBiasie-Sammons who endured spotty skype meetings during my semester abroad and has been a tremendous help every step of the way, to Giampiero Bevagna who helped translate Italian books and articles and showed our archaeology class necropoleis of Etruria, and to Dr. Brooke Porter who helped me see my research through the eyes of a marine biologist.