Reading Joshua As Christian Scripture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Killing Us Softly 4 Advertising’S Image of Women

MEDIA EDUCATION FOUNDATION STUDY GUIDE Killing Us Softly 4 Advertising’s Image of Women Study Guide by Kendra Hodgson Edited by Jeremy Earp and Jason Young 2 CONTENTS Note to Educators 3 Program Overview 3 Pre-viewing Questions for Discussion & Writing 4 Key Points 5 Post-viewing Questions for Discussion & Writing 9 Assignments 11 Semester-Long Project 14 For additional assignments, please download the Killing Us Softly 3 study guide: http://www.mediaed.org/assets/products/206/studyguide_206.pdf For handouts associated with the Killing Us Softly 3 study guide, also download: http://www.mediaed.org/assets/products/206/studyguidehandout_206.pdf © The Media Education Foundation | www.mediaed.org 3 NOTE TO EDUCATORS This study guide is designed to help you and your students engage and manage the information presented in this video. Given that it can be difficult to teach visual content – and difficult for students to recall detailed information from videos after viewing them – the intention here is to give you a tool to help your students slow down and deepen their thinking about the specific issues this video addresses. With this in mind, we’ve structured the guide to help you stay close to the video’s main line of argument as it unfolds: Key Points provide a concise and comprehensive summary of the video. They are designed to make it easier for you and your students to recall the details of the video during class discussions, and as a reference point for students as they work on assignments. Questions for Discussion & Writing encourage students to reflect critically on the video during class discussions, and guide their written reactions before and after these discussions. -

The Perfect Sacrifice Lesson Focus | Since His Beginning, Man Has Always Offered Sacrifices to God in Order to Atone for His Sins

St. Mary's At-Home Guide - February 24 (Ch 20-21) - Grade 5 Lesson 20 The Perfect Sacrifice Lesson Focus | Since his beginning, man has always offered sacrifices to God in order to atone for his sins. No sacrifice, however, could truly atone for sin because no sacrifice was perfect. Jesus’ offering of himself on the Cross, however, was. That’s because Jesus, who both offered the sacrifice and was the sacrifice, was perfect. At every Mass, Jesus, through the priest, continues to offer himself to God when the bread and wine are transformed into his Body and Blood. It is the same sacrifice offered on Calvary, re–presented in time. 1 | begin Pray the Glory Be with your child. Show your child pictures of sheep, goats, calves, doves, wheat, and wine. Explain that if you had lived in Jerusalem during Jesus’ time, your family would have gone to the temple to give these items to the priest for sacrifice. Together read John 1:19–30 aloud. 2 | summarize Summarize this week’s lesson for your child: Example: When Jesus offered his life on the Cross, he became the one, perfect sacrifice, the Lamb of God offered up for all the world’s sins. After that, it was no longer necessary for people to offer up other ritual sacrifices, such as goats, lambs, and doves. 3 | review References Review this week’s lesson by asking your child the following questions: Student Textbook: 1. What is a sacrifice? (The offering up of something to God.) Chapter 20, pp. 83–86 2. -

Battle of Jericho and Rahab LESSON Joshua 1-4 10

The Battle of Jericho and Rahab LESSON Joshua 1-4 10 Old Testament 4 Part 2: Joshua Leads God’s People SUNDAY MORNING Old Testament 4 Class Attendance Sheet provided in activity sheets (NOTE: The document is interactive, allowing the teacher to type in the Class, Teacher, and the children’s names.) SCRIPTURE REFERENCES: Joshua 1-4; 6; Hebrews 11:30-31; James 2:25 MEMORY WORK: YOUNGER CHILDREN: “…[D]o not be afraid…for the Lord your God is with you wherever you go” (Joshua 1:9). OLDER CHILDREN: “Be strong and of good courage; do not be afraid, nor be dismayed, for the Lord your God is with you wherever you go” (Joshua 1:9). SONGS AND FINGERPLAYS (SEE END OF LESSON FOR WORDS): A song book and audio recordings of many of the curriculum songs are available on the curriculum Web site. • “Rahab and the Spies” • “Walls of Jericho” • “Israel Crosses Jordan into Canaan” • “Jericho’s Falling” • “Fall of Jericho” LESSON VISUALS AND TEACHING AIDS (NOTE ANY DISCLAIMERS): • See AP’s Pinterest page for ideas on bulletin boards, visuals, crafts, etc. [DISCLAIMER: Pins may sometimes need to be adjusted to be Scriptural.] • God’s People and Joshua Bible fact cards (provided under “O.T. 4 Bible Facts” on curriculum Web site) • “Summary of the Bible” from “Kids Prep” CD by Jeff Miller • Betty Lukens’ felt pieces • Joshua A Beka Flash-A-Card Series (DISCLAIMER: use the cards, not the lesson book) • Map of the Conquest of Canaan (provided in map section of curriculum Web site) 3/1/18 www.apologeticspress.org Page 75 O.T. -

Download Download

British Journal for Military History Volume 7, Issue 1, March 2021 What’s in a name? Identifying military engagements in Egypt and the Levant, 1915-1918 Roslyn Shepherd King Pike ISSN: 2057-0422 Date of Publication: 19 March 2021 Citation: Roslyn Shepherd King Pike, ‘What’s in a name? Identifying military engagements in Egypt and the Levant, 1915-1918’, British Journal for Military History, 7.1 (2021), pp. 87-112. www.bjmh.org.uk This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. The BJMH is produced with the support of IDENTIFYING MILITARY ENGAGEMENTS IN EGYPT & THE LEVANT 1915-1918 What’s in a name? Identifying military engagements in Egypt and the Levant, 1915- 1918 Roslyn Shepherd King Pike* Independent Scholar Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT This article examines the official names listed in the 'Egypt and Palestine' section of the 1922 report by the British Army’s Battles Nomenclature Committee and compares them with descriptions of military engagements in the Official History to establish if they clearly identify the events. The Committee’s application of their own definitions and guidelines during the process of naming these conflicts is evaluated together with examples of more recent usages in selected secondary sources. The articles concludes that the Committee’s failure to accurately identify the events of this campaign have had a negative impacted on subsequent historiography. Introduction While the perennial rose would still smell the same if called a lily, any discussion of military engagements relies on accurate and generally agreed on enduring names, so historians, veterans, and the wider community, can talk with some degree of confidence about particular events, and they can be meaningfully written into history. -

College Comeback: ODHE Formal Guidance

College Comeback A Summary of Ohio Law and Policy on Outstanding Student Balances Owed and Debt-Forgiveness Models that Can Be Applied in Ohio Approximately 1.5 million Ohioans have some college, but no degree (or credential). This presents a critical challenge to maximizing the economic opportunity for that individual as well as for the greater good of the State of Ohio’s economy. These students enrolled in post-secondary education seeking a degree, but we didn’t get them across the finish line. If we successfully help Ohioans enjoy a “college comeback” resulting in a degree (or credential), we can make significant strides toward increasing Ohio’s educational attainment, improving expected gross domestic product, average wages, employment rate and Ohio’s economy. Among the barriers to a college comeback for this population are past-due debts owed to institutions of higher education at which they were previously enrolled, nearly always resulting in an inability to receive a transcript to complete college elsewhere. Facing these barriers, many students opt never to return and complete their degree. In recent years, some institutions of higher education – notably Cleveland State University, Clark State College, Lorain County Community College, Stark State College, and Zane State College right here in Ohio – have begun to offer new debt forgiveness programs. Cleveland State is currently offering up to $5,000 in debt forgiveness – among the best offers we’ve seen nationally. Lorain and Clark State are both offering up to $1,000 in debt relief. A national example is Wayne State University in Detroit. The “Warrior Way Back” program forgives up to $1,500. -

The Conquest of the Promised Land: Joshua

TABLE OF CONTENTS Brief Explanation of the Technical Resources Used in the “You Can Understand the Bible” Commentary Series .............................................i Brief Definitions of Hebrew Grammatical Forms Which Impact Exegesis.............. iii Abbreviations Used in This Commentary........................................ix A Word From the Author: How This Commentary Can Help You.....................xi A Guide to Good Bible Reading: A Personal Search for Verifiable Truth ............. xiii Geographical Locations in Joshua.............................................xxi The Old Testament as History............................................... xxii OT Historiography Compared with Contemporary Near Eastern Cultures.............xxvi Genre and Interpretation: Old Testament Narrative............................. xxviii Introduction to Joshua ................................................... 1 Joshua 1.............................................................. 7 Joshua 2............................................................. 22 Joshua 3............................................................. 31 Joshua 4............................................................. 41 Joshua 5............................................................. 51 Joshua 6............................................................. 57 Joshua 7............................................................. 65 Joshua 8............................................................. 77 Joshua 9............................................................ -

Between Belief and Delusion: Cult Members and the Insanity Plea

REGULAR ARTICLE Between Belief and Delusion: Cult Members and the Insanity Plea Brian Holoyda, MD, MPH, and William Newman, MD Cults are charismatic groups defined by members’ adherence to a set of beliefs and teachings that differ from those of mainstream religions. Cult beliefs may appear unusual or bizarre to those outside of the organization, which can make it difficult for an outsider to know whether a belief is cult-related or delusional. In accordance with these beliefs, or at the behest of a charismatic leader, some cult members may participate in violent crimes such as murder and later attempt to plead not guilty by reason of insanity (NGRI). It is therefore necessary for forensic experts who evaluate cult members to understand how the court has responded to such individuals and their beliefs when they mount a defense of NGRI for murder. Based on a review of extant appellate court case law, cult member defendants have not yet successfully pleaded NGRI on the basis of cult involvement, despite receiving a broad array of psychiatric diagnoses that could qualify for such a defense. With the reintroduction of cult involvement in the DSM-5 criteria for other specified dissociative disorder, however, there may be a resurgence of dissociative-type diagnoses in future cult-related cases, both criminal and civil. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 44:53–62, 2016 Cults are generally considered to be new charismatic organization. Because of this perception, it can be groups that espouse religious doctrine that differs difficult for an outsider to know whether a belief is from mainstream beliefs. -

THE RAIDS ACROSS the JORDAN Thecapture of Jericho and the West Bank of the Jordan Was Only the First Stage of Operations of the Utmost Importance

CHAPTER IX THE RAIDS ACROSS THE JORDAN THEcapture of Jericho and the west bank of the Jordan was only the first stage of operations of the utmost importance. The Jordan position was more than a good defensive flank; it offered an opening for attack, with good prospects of success, against the Turkish communications along the Hejaz railway. The Sherifian Arabs were still raiding the enemy south of El Kutrani, and in early March were present in some force about Et Tafile. Turkish columns from Kerak, to the north, and from the railway, on the east, drove them out of Et Tafile on March rrth, but a week later had withdrawn again to their camps on the railway. It was deemed to be of the highest importance to interrupt the communications of these Turkish troops by cutting the railway about Amman, and especially by destroying a railway viaduct at the south of that town. Moreover, the Bedouin tribes about Madeba were inclined to hostility against the Turks, and it was held that any successful operations against Amman might count to some extent on their co-operation. Hence the great raids of March and April against Amman, Es Salt, and the Turkish garrisons east of the Jordan had a direct importance, evidenced in the event by the enemy’s sensitiveness. They had also an indirect result of the greatest possible value. as subsequently appeared. In these spring operations Allenby probably builded better than he knew. When the time came for the final assault which destroyed the Turkish armies, the enemy was still inclined to suspect that the British intended to attack across the Jordan rather than along the Mediterranean coast. -

You Can Download the Booklet Researching Your Relatives Military

SEMINAR NOTES Organisers 3rd Auckland (Countess of Ranfurly’s Own) & Northland Battalion Group 3rd Auckland & Northland Regimental Association Auckland War Memorial Museum Passchendaele Society Returned & Services Association - Auckland Branch 2 INDEX Acknowledgement .………………………………………………….……..….. 2 The Boer War (1899 — 1902) ………………………………….………….. 3 NZ Army 1907 — 1911 Infantry Units …………………………………………………….……… 5 Mounted Rifles Units ……………………………….…….………… 6 World War I (The Great War) ………………………….…….…………… 7 1 NZEF Samoa 1914 — 1918 Gallipoli 1915 Belgium & France 1916 — 1918 Mounted Rifles 1914 — 1919 World War II ………………………………………………………………………... 8 2 NZEF (2 (NZ) Division) Greece and Crete 1940 North Africa 1940 — 1943 Italy 1943 — 1945 2 NZEF (IP) (3 (NZ) Division) The Pacific 1940 — 1944………………….…………….. 10 Jargon and Abbreviations …..……………………….…………….. 11 Other Data Sources …………………………………………………….……… 12 Medals Description …………………………………………….…………….... 14 Illustrations ………………………………………….…………………… 16 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The organizers of these seminars say thanks, on behalf of all who use this Data, to our Financial Donors and the Printer who made this booklet possible. 3 Boer War Contingents 1899 — 1902 Contingent Strength Units Departed Date Ship 1st 215 1st Mounted Rifles Wellington 21/10/99 SS Waiwera 1 and 2 Company 2nd 266 Wellington 20/01/00 SS Waiwera Hotchkiss Machine Gun Canterbury Company 3rd 262 Hawkes Bay Wanganui Lyttleton 17/02/00 SS Knight Templar Taranaki & Manawatu Company 9 and 10 Company Port Chalmers 25/03/00 SS Gymeric 4th 462 7 and 8 -

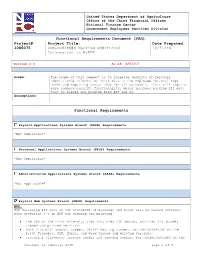

Functional Requirements Document (FRD) Project# Project Title: Date Prepared: 1086075 PPS-CR#29689 Masking Additional 10/31/16 Information in Myepp

United States Department of Agriculture Office of the Chief Financial Officer National Finance Center Government Employees Services Division Functional Requirements Document (FRD) Project# Project Title: Date Prepared: 1086075 PPS-CR#29689 Masking Additional 10/31/16 Information in MyEPP Version 2.0 As of: 3/07/17 Scope: The scope of this request is to increase security of Personal Identifiable Information (PII) data in the Employee Personal Page (EPP) and Reporting Center (RC) for all customers. This will require more complex security functionality, which includes masking PII data that is viewed and printed from EPP and RC. Assumptions: Functional Requirements Payroll Applications Systems Branch (PASB) Requirements “Not Applicable” Personnel Applications Systems Branch (PESB) Requirements “Not Applicable” Administrative Applications Systems Branch (AASB) Requirements “Not Applicable” Payroll Web Systems Branch (PWSB) Requirements EPP: The following PII data on the Statement of Earnings and Leave will be masked entirely with asterisks (*) in EPP for viewing and printing: The SSN on the Print Friendly, View PDF, View DOC (Word), and View Xls (Excel) viewed and printed versions. Bank financial account number, DD/EFT Routing numbers for CHKING/SAVING on the Print Friendly, PDF, Excel, and Word viewed and printed versions. Financial allotments account number and routing numbers for CHKING/SAVINGS on the Version: 11 February 2015 Page 1 of 5 Functional Requirements Document (FRD) Project# Project Title: Date Prepared: 1086075 PPS-CR#29689 Masking Additional Information in 10/31/16 MyEPP Print Friendly, PDF, Excel, and Word viewed and printed versions. Discretionary allotments account number and routing numbers for CHKING/SAVINGS on the Print Friendly, PDF, Excel, and Word viewed and printed versions. -

The Techniques of the Sacrifice

Andm Univcrdy Seminary Stndics, Vol. 44, No. 1,13-49. Copyright 43 2006 Andrews University Press. THE TECHNIQUES OF THE SACRIFICE OF ANIMALS IN ANCIENT ISRAEL AND ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA: NEW INSIGHTS THROUGH COMPARISON, PART 1' JOANNSCURLOCK ELMHURSTCOLLEGE Elmhurst, Illinois There is an understandable desire among followers of religions that are monotheistic and that claim descent from ancient Israelite religion to see that religion as unique and completely at odds with its surroundrng polytheistic competitors. Most would not deny that there are at least a few elements of Israelite religion that are paralleled in neighboring cultures, as, e.g., the Hittites: 'I would like to thank the following persons who read and commented on earlier drafts of this article: R. Bed, M. Hilgert, S. Holloway, R. Jas, B. Levine and M. Murrin. Abbreviations follow those given in W. von Soden, AWches Han&rterbuch, 3 301s. (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1965-1981); and M. Jursa and M. Weszeli, "Register Assyriologie," AfO 40-41 (1993/94): 343-369, with the exception of the following: (a) series: D. 0.Edzard, Gnda and His Dynarg, Royal Inscriptions of Mesopommia: Early Periods (RIME) 311 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997); S. Parpola and K. Watanabe, Neo-Assyrin Treatzes and Lq&y Oaths, State Archives of Assyria (SAA) 2 (Helsinki: Helsinki University Press, 1988); A. Livingstone, Court Poety and Literq Misceubnea, SAA 3 (Helsinki Helsinki University Press, 1989); I. Starr,QnerieJ to the Sungod, SAA 4 (Helsinki Helsinki University Press, 1990); T. Kwasrnan and S. Parpola, Lga/ Trama~~lom$the RoyaiCoz& ofNineveh, Part 1, SAA 6 (Helsinki Helsinki University Press, 1991); F. -

“On the Third Day”: the Time Frame of Jesus' Death And

JETS 56/3 (2013) 511–42 “ON THE THIRD DAY”: THE TIME FRAME OF JESUS’ DEATH AND RESURRECTION MARTIN PICKUP* I. INTRODUCTION The three-day time frame of Jesus’ death and resurrection was a part of the earliest Christian preaching. It had a place in the kerygmatic formula that Paul quotes in 1 Cor 15:3–5, a four-line formula that is generally acknowledged to have originated in the very earliest years of the Church.1 For I delivered to you as of first importance what I also received, that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures, and that He was buried, and that He was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures, and that He appeared to Cephas, then to the twelve.2 * Editor’s note: Martin Pickup unexpectedly passed away shortly after submitting this piece for pub- lication. This article reflects his interest and expertise in the Jewish background to the NT and in the early church’s proclamation of the bodily resurrection of Jesus. His family, friends, and many former students rejoice in the hope Marty defended with such skill in this article. “So also in Christ shall all be made alive” (1 Cor 15:22). 1 Scholars across the theological spectrum acknowledge the earliness of this formula. Most assign it a date of no more than two to five years after Jesus’ crucifixion. See, e.g., K. Lake, The Historical Evidence for the Resurrection of Jesus Christ (London: Williams and Norgate, 1907) 37–43; J. J. Smith, “Resurrection Faith Today,” TS 30 (1969) 403–4; G.