The Techniques of the Sacrifice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Justice in an Open World – the Role Of

E c o n o m i c & Social Affairs The International Forum for Social Development Social Justice in an Open World The Role of the United Nations Sales No. E.06.IV.2 ISBN 92-1-130249-5 05-62917—January 2006—2,000 United Nations ST/ESA/305 DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL AFFAIRS Division for Social Policy and Development The International Forum for Social Development Social Justice in an Open World The Role of the United Nations asdf United Nations New York, 2006 DESA The Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat is a vital interface between global policies in the economic, social and environmental spheres and national action. The Department works in three main interlinked areas: (i) it compiles, generates and analyses a wide range of economic, social and environ- mental data and information on which States Members of the United Nations draw to review common problems and to take stock of policy options; (ii) it facilitates the negotiations of Member States in many intergovernmental bodies on joint course of action to address ongoing or emerging global challenges; and (iii) it advises inter- ested Governments on the ways and means of translating policy frameworks devel- oped in United Nations conferences and summits into programmes at the country level and, through technical assistance, helps build national capacities. Note The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the United Nations. The designations employed and the presentation of the mate- rial do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitations of its frontiers. -

(Mk 1:44): Jesus, Purity, and the Christian Study of Judaism Paula Fredriksen, Boston University

"Go, show yourself to the priest, and offer for your cleansing what Moses commanded" (Mk 1:44): Jesus, Purity, and the Christian Study of Judaism Paula Fredriksen, Boston University In the last century, and especially in the last few decades, historians of Christianity have increasingly understood Jesus of Nazareth as a participant in the Judaism of his day. Many scholars, however, even when emphasizing Jesus' Jewish ethics, or his Jewish scriptural sensibility, or even the apocalyptic convictions which he shared with so many of his contemporaries, nevertheless draw the line at the biblical laws of purity. These laws rarely appear realistically integrated into an historical reconstruction of Jesus. Allied as they are with the ancient system of sacrifices, they seem obscure to modern religious sensibility; and with the Roman destruction of the Temple in 70, they soon became irrelevant to the later, largely Gentile church. Perhaps, too, such purity codes -- a hallmark of virtually all ancient religions -- are too disturbingly archaic to fit comfortably with modern constructions of Jesus and his message. Very recently, a handful of prominent New Testament historians and theologians have even argued that Jesus taught and acted specifically against the purity codes of his native Judaism. The repudiation of the biblical rules of purity, "the taboos of Torah," stood, they say, at the very heart of Jesus' ministry. Marcus Borg, for example, has urged that Jesus fought the "politics of purity," motivated as he was by a vision of a more compassionate society. Similarly, John Dominic Crossan portrays Jesus as a radical social egalitarian for whom the purity codes of the Temple system were morally and socially anathema. -

A HISTORY of the HEBREW TABERNACLE CONGREGATION of WASHINGTON HEIGHTS a German-Jewish Community in New York City

A HISTORY OF HEBREW TABERNACLE A HISTORY OF THE HEBREW TABERNACLE CONGREGATION OF WASHINGTON HEIGHTS A German-Jewish Community in New York City With An Introduction by Rabbi Robert L. Lehman, D. Min., D.D. December 8, 1985 Chanukah, 5746 by Evelyn Ehrlich — 1 — A HISTORY OF HEBREW TABERNACLE THANK YOU Many individuals have contributed toward making this project possible, not the least of which were those who helped with their financial contributions. They gave “in honor” as well as “in memory” of individuals and causes they held dear. We appreciate their gifts and thank them in the name of the congregation. R.L.L. IN MEMORY OF MY DEAR ONES by Mrs. Anna Bondy TESSY & MAX BUCHDAHL by their loved ones, Mr. and Mrs. Ernst Grumbacher HERBERT KANN by his wife, Mrs. Lore Kann FRED MEYERHOFF by his wife, Mrs. Rose Meyerhoff ILSE SCHLOSS by her husband, Mr. Kurt J. Schloss JULIUS STERN by his wife, Mrs. Bella Stern ROBERT WOLEMERINGER by his wife, Mrs. Friedel Wollmeringer IN HONOR OF AMY, DEBORAH & JOSHUA BAUML by their grandmother, Mrs. Elsa Bauml the CONGREGATION by Mrs. Gerda Dittman, Mr. & Mrs. Paul Ganzman, Ms. Bertha Kuba, Mr. & Mrs. Nathan Maier, Mrs. Emma Michel, Mrs. Ada Speyer (deceased 1984), Mrs. Joan Wickert MICHELLE GLASER and STEVEN GLASER by their grandmother, Mrs. Anna Bondy RAQUEL and RUSSELL PFEFFER by their grandparents, Mr. and Mrs. Rudolph Oppenheimer HANNA ROTHSTEIN by her friend, Mrs. Stephanie Goldmann and by two donors who wish to remain anonymous — 2 — A HISTORY OF HEBREW TABERNACLE INTRODUCTION Several factors were instrumental in the writing of this history of our congregation. -

Idolatry in the Ancient Near East1

Idolatry in the Ancient Near East1 Ancient Near Eastern Pantheons Ammonite Pantheon The chief god was Moloch/Molech/Milcom. Assyrian Pantheon The chief god was Asshur. Babylonian Pantheon At Lagash - Anu, the god of heaven and his wife Antu. At Eridu - Enlil, god of earth who was later succeeded by Marduk, and his wife Damkina. Marduk was their son. Other gods included: Sin, the moon god; Ningal, wife of Sin; Ishtar, the fertility goddess and her husband Tammuz; Allatu, goddess of the underworld ocean; Nabu, the patron of science/learning and Nusku, god of fire. Canaanite Pantheon The Canaanites borrowed heavily from the Assyrians. According to Ugaritic literature, the Canaanite pantheon was headed by El, the creator god, whose wife was Asherah. Their offspring were Baal, Anath (The OT indicates that Ashtoreth, a.k.a. Ishtar, was Baal’s wife), Mot & Ashtoreth. Dagon, Resheph, Shulman and Koshar were other gods of this pantheon. The cultic practices included animal sacrifices at high places; sacred groves, trees or carved wooden images of Asherah. Divination, snake worship and ritual prostitution were practiced. Sexual rites were supposed to ensure fertility of people, animals and lands. Edomite Pantheon The primary Edomite deity was Qos (a.k.a. Quas). Many Edomite personal names included Qos in the suffix much like YHWH is used in Hebrew names. Egyptian Pantheon2 Egyptian religion was never unified. Typically deities were prominent by locale. Only priests worshipped in the temples of the great gods and only when the gods were on parade did the populace get to worship them. These 'great gods' were treated like human kings by the priesthood: awakened in the morning with song; washed and dressed the image; served breakfast, lunch and dinner. -

Burn Your Way to Success Studies in the Mesopotamian Ritual And

Burn your way to success Studies in the Mesopotamian Ritual and Incantation Series Šurpu by Francis James Michael Simons A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Classics, Ancient History and Archaeology School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham March 2017 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The ritual and incantation series Šurpu ‘Burning’ is one of the most important sources for understanding religious and magical practice in the ancient Near East. The purpose of the ritual was to rid a sufferer of a divine curse which had been inflicted due to personal misconduct. The series is composed chiefly of the text of the incantations recited during the ceremony. These are supplemented by brief ritual instructions as well as a ritual tablet which details the ceremony in full. This thesis offers a comprehensive and radical reconstruction of the entire text, demonstrating the existence of a large, and previously unsuspected, lacuna in the published version. In addition, a single tablet, tablet IX, from the ten which comprise the series is fully edited, with partitur transliteration, eclectic and normalised text, translation, and a detailed line by line commentary. -

Unmet Promises: Continued Violence and Neglect in California's Division

UNMET PROMISES Continued Violence & Neglect in California’s Division of Juvenile Justice Maureen Washburn | Renee Menart | February 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements 4 Executive Summary 7 History 9 Youth Population 10 A. Increased spending amid a shrinking system 10 B. Transitional age population 12 C. Disparate confinement of youth of color 13 D. Geographic disparities 13 E. Youth offenses vary 13 F. Large facilities and overcrowded living units 15 Facility Operations 16 A. Aging facilities in remote areas 16 B. Prison-like conditions 18 C. Youth lack safety and privacy in living spaces 19 D. Poorly-maintained structures 20 Staffing 21 A. Emphasis on corrections experience 21 B. Training focuses on security over treatment 22 C. Staffing levels on living units risk violence 23 D. Staff shortages and transitions 24 E. Lack of staff collaboration 25 Violence 26 A. Increasing violence 26 B. Gang influence and segregation 32 C. Extended isolation 33 D. Prevalence of contraband 35 E. Lack of privacy and vulnerability to sexual abuse 36 F. Staff abuse and misconduct 38 G. Code of silence among staff and youth 42 H. Deficiencies in the behavior management system 43 Intake & Unit Assignment 46 A. Danger during intake 46 B. Medical discontinuity during intake 47 C. Flaws in assessment and case planning 47 D. Segregation during facility assignment 48 E. Arbitrary unit assignment 49 Medical Care & Mental Health 51 A. Injuries to youth 51 B. Barriers to receiving medical attention 53 C. Gender-responsive health care 54 D. Increase in suicide attempts 55 E. Mental health care focuses on acute needs 55 Programming 59 A. -

Thetorah -Com

6t9t2U2U I ne Paraoox oI Pesacn :inenr - | ne I oran.com TheTorah -com The Paradox of Pesach Sheni As a historical commemoration, Passover is tied to a specific date. Nevertheless, the Torah gives a make-up date for bringing the offering a month later. Gerim, non- Israelites living among Israelites as equals, are also allowed to bring this offering, even though it wasn)t their ancestors who were freed. How do we make sense of these anomalies? Prof. Steven Fraade u* ntrs .!i.aitrir! i'irir;ri{,r I t i I I 5* \} - A Fixed Lunar-Calendrical Commemoration: A fter explaining to Moses how the Israelites should perform the Passover I I ritual in order to avoid being killed during the plague of the firstborn, YHWH endswith: El? nll triri nin] T:rr ntDur ExodD:14 This day shallbe to you one of ;r:;r-! rf inx onirrlr firpr5 remembrance: you shall celebrate it as a hltns'//unrnrr thelnrah enm/artinlc/the-naradav-nf-nceanh-ehpni 1 111 6t9t2U2t) I he Paradox ot Pesach shent - | ne loran.com .r;lilT tr?i9 ni?l;| tr)!I-r1' festival to YHWH throughout the ages; you shall celebrate it as an institution for all time. Moses then passes the message along to the elders of Israel, expanding on this point: 'D:r' niDu' Exod'12:2t+ l?:Tn n$ trR"lDt?l You shall observe this as an .o?ip ru Tt;}'r! il4);'rrn institution for all time, for you and for ;'1):r' f':lqt? tli tNff '? i"l';r'l your descendants. -

Backyard Farming and Slaughtering 2 Keeping Tradition Safe

Backyard farming and slaughtering 2 Keeping tradition safe FOOD SAFETY TECHNICAL TOOLKIT FOR ASIA AND THE PACIFIC Backyard farming and slaughtering – Keeping tradition safe Backyard farming and slaughtering 2 Keeping tradition safe FOOD SAFETY TECHNICAL TOOLKIT FOR ASIA AND THE PACIFIC Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Bangkok, 2021 FAO. 2021. Backyard farming and slaughtering – Keeping tradition safe. Food safety technical toolkit for Asia and the Pacific No. 2. Bangkok. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. © FAO, 2021 Some rights reserved. This work is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO license (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this license, this work may be copied, redistributed and adapted for non- commercial purposes, provided that the work is appropriately cited. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that FAO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the FAO logo is not permitted. -

ANIMAL SACRIFICE in ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIAN RELIGION The

CHAPTER FOURTEEN ANIMAL SACRIFICE IN ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIAN RELIGION JOANN SCURLOCK The relationship between men and gods in ancient Mesopotamia was cemented by regular offerings and occasional sacrifices of ani mals. In addition, there were divinatory sacrifices, treaty sacrifices, and even "covenant" sacrifices. The dead, too, were entitled to a form of sacrifice. What follows is intended as a broad survey of ancient Mesopotamian practices across the spectrum, not as an essay on the developments that must have occurred over the course of several millennia of history, nor as a comparative study of regional differences. REGULAR OFFERINGS I Ancient Mesopotamian deities expected to be fed twice a day with out fail by their human worshipers.2 As befitted divine rulers, they also expected a steady diet of meat. Nebuchadnezzar II boasts that he increased the offerings for his gods to new levels of conspicuous consumption. Under his new scheme, Marduk and $arpanitum were to receive on their table "every day" one fattened ungelded bull, fine long fleeced sheep (which they shared with the other gods of Baby1on),3 fish, birds,4 bandicoot rats (Englund 1995: 37-55; cf. I On sacrifices in general, see especially Dhorme (1910: 264-77) and Saggs (1962: 335-38). 2 So too the god of the Israelites (Anderson 1992: 878). For specific biblical refer ences to offerings as "food" for God, see Blome (1934: 13). To the term tamid, used of this daily offering in Rabbinic sources, compare the ancient Mesopotamian offering term gimi "continual." 3 Note that, in the case of gods living in the same temple, this sharing could be literal. -

Theories of Sacrifice and Ritual

UC Davis UC Davis Previously Published Works Title Inventing the Scapegoat: Theories of Sacrifice and Ritual Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/055689pg Journal Journal of Ritual Studies, 25(1) Author Janowitz, Naomi Publication Date 2011 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Inventing the Scapegoat: Theories of Sacrifice and Ritual No figure appears in studies of sacrifice more often than the scapegoat. Numerous societies, the argument goes, have a seemingly innate need to purge sins via an innocent victim. The killing of this victim constitutes the core of sacrifice traditions; explaining the efficacy of these rites outlines in turn the inner workings of all sacrifices, if not all rituals. I do not believe, however, that the enigmatic figure of the scapegoat can support a universal theory of sacrifice, especially if the general term “scapegoat” turns out refer to a variety of rituals with very different goals. Rene Girard’s extremely influential theory of the scapegoat includes a biological basis for the importance of the figure (Girard, 1977). According to Girard, humans are naturally aggressive, a la Konrad Lorenz. This innate aggression was channeled into an unending series of attacks and counterattacks during the earliest periods of history. A better outlet for aggression was to find a scapegoat whose death would stop the cycle of retribution (p. 2). For Girard, Oedipus was a human scapegoat, placing this model 2 at the center of Greek culture in addition to Biblical religious traditions (p. 72). Jonathan Smith’s observations on Girard’s model in “The Domestication of Sacrifice” are both simple and devastating (1987). -

Judeans in Babylonia a Study of Deportees in the Sixth and Fifth Centuries BCE

Tero Alstola Judeans in Babylonia A Study of Deportees in the Sixth and Fifth Centuries BCE ACADEMIC DISSERTATION TO BE PUBLICLY DISCUSSED, BY DUE PERMISSION OF THE FACULTY OF THEOLOGY AT THE UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI IN AUDITORIUM XII OF THE UNIVERSITY MAIN BUILDING, ON THE 17TH OF JANUARY, 2018 AT 12 O’CLOCK. This dissertation project has been financially supported by the ERC Starting Grant project ‘By the Rivers of Babylon: New Perspectives on Second Temple Judaism from Cuneiform Texts’ and by the Centre of Excellence in Changes in Sacred Texts and Traditions, funded by the Academy of Finland. Cover illustration by Suvi Tuominen ISBN 978-951-51-3831-6 (paperback) ISBN 978-951-51-3832-3 (PDF) Unigrafia Oy Helsinki 2017 SUMMARY Judeans in Babylonia: A Study of Deportees in the Sixth and Fifth Centuries BCE The dissertation investigates Judean deportees in Babylonia in the sixth and fifth centuries BCE. These people arrived in Babylonia from Judah in the early sixth century BCE, being but one of numerous ethnic groups deported and resettled by King Nebuchadnezzar II. Naming practices among many deportee groups have been thoroughly analysed, but there has been little interest in writing a socio-historical study of Judeans or other immigrants in Babylonia on the basis of cuneiform sources. The present dissertation fills this gap by conducting a case study of Judean deportees and placing its results in the wider context of Babylonian society. The results from the study of Judeans are evaluated by using a group of Neirabian deportees as a point of comparison. The sources of this study consist of 289 clay tablets written in Akkadian cuneiform. -

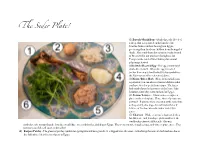

The Seder Plate

Te Seder Plate! (1) Zaroah/Shank Bone - Symbolizes the blood of a sheep that was painted on the lintels of the Israelite homes on their last night in Egypt, protecting their firstborn children from the angel of death. Also symbolizes the sacrifice for the festival of Passover that our ancestors brought to the Temple in the land of Israel during this annual pilgrimage festival. (2)Beitzah/Roasted Egg - The egg is round and symbolizes rebirth. When the egg is roasted (rather than simply hard boiled) it also symbolizes the Passover sacrifice referenced above. (3)Maror/Bitter Herb - Here, horseradish paste is pictured; you can also use horseradish root that you have sliced or peeled into strips. The bitter herb symbolizes the bitterness of the lives of the Israelites when they were enslaved in Egypt. (4) Potato/Lettuce - Often lettuce occupies a place on the seder plate. Here, slices of potato are pictured. If potato, these are eaten at the same time as the parsley, also dipped in salt water (6) or if lettuce, at the time when the bitter herb (3) is eaten. (5) Charoset - While everyone’s charoset looks a bit different - and Jewish people from all over the world make charoset differently - this mix symbolizes the mortar that the Israelites would have used with bricks, building in Egypt. This is often a mix of apples, nuts, and wine or grape juice. This sweetness is a beloved taste of the seder! (6) Karpas/Parsley - The green of parsley symbolizes springtime and new growth. It is dipped into salt water, symbolizing the tears of the Israelites due to the difficulty of their lives in slavery in Egypt..