Thetorah -Com

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zelophehad's Daughters

Zelophehad’s Daughters July 2011 I would like to start off tonight by trying to articulate just how excited I am to be here. In my two weeks at Shomrei Torah, the deep abundance of love and support from members, staff, Rabbi George and every person who has walked through the doors has been remarkable. I could not have dreamed of a better start for my rabbinical career. It is also exciting to me that this week’s Torah portion is Pinchas, not so much for the broad story but, rather, for the story of Zelophehad’s daughters that is tucked away inside. The first few years of rabbinical school, I was struck by the strong feminist nature of some of my classmates and teachers. Back then, I would not have considered myself to be a feminist. So as I started to prepare to speak tonight, I tried very hard to shy away from speaking about Zelophehad’s daughters. Yet I just couldn’t give up the opportunity to talk about one of my favorite episodes in the Torah. I love this story, because it tells the triumphant tale of the very first feminist activists. The story of Zelophehad’s daughters actually appears in the Bible three times. The first time they are mentioned is in this week’s portion. The story introduces us to the daughters of Zelophehad, Mahlah, Noah, Hoglah, Milcah, and Tirzah. Let’s look at them together. The portion begins as God instructs Moses and Eliazar to conduct a widespread census of the people. God then instructs Moses to distribute lots of land in proportion to the enrolment of the group. -

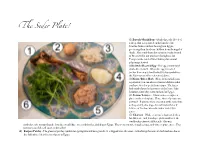

The Seder Plate

Te Seder Plate! (1) Zaroah/Shank Bone - Symbolizes the blood of a sheep that was painted on the lintels of the Israelite homes on their last night in Egypt, protecting their firstborn children from the angel of death. Also symbolizes the sacrifice for the festival of Passover that our ancestors brought to the Temple in the land of Israel during this annual pilgrimage festival. (2)Beitzah/Roasted Egg - The egg is round and symbolizes rebirth. When the egg is roasted (rather than simply hard boiled) it also symbolizes the Passover sacrifice referenced above. (3)Maror/Bitter Herb - Here, horseradish paste is pictured; you can also use horseradish root that you have sliced or peeled into strips. The bitter herb symbolizes the bitterness of the lives of the Israelites when they were enslaved in Egypt. (4) Potato/Lettuce - Often lettuce occupies a place on the seder plate. Here, slices of potato are pictured. If potato, these are eaten at the same time as the parsley, also dipped in salt water (6) or if lettuce, at the time when the bitter herb (3) is eaten. (5) Charoset - While everyone’s charoset looks a bit different - and Jewish people from all over the world make charoset differently - this mix symbolizes the mortar that the Israelites would have used with bricks, building in Egypt. This is often a mix of apples, nuts, and wine or grape juice. This sweetness is a beloved taste of the seder! (6) Karpas/Parsley - The green of parsley symbolizes springtime and new growth. It is dipped into salt water, symbolizing the tears of the Israelites due to the difficulty of their lives in slavery in Egypt.. -

The Torah: a Women's Commentary

Study Guide The Torah: A Women’s Commentary Parashat Mas’ei Numbers 33:1-36:13 Study Guide written by Rabbi Stephanie Bernstein dr. tamara Cohn eskenazi, dr. Lisa d. Grant, and Rabbi Andrea L. Weiss, Ph.d., editors Rabbi Hara e. Person, series editor Parashat Mas’ei Study Guide themes theme 1: Recalling the Journey: it’s Been a Long and Winding Road theme 2: ensuring Justice in the Promised Land: Providing Cities of Refuge theme 3: Amending God’s Law in the Promised Land: the Limits of individual Freedom Introduction arashat Mas’ei begins with a detailed review of the israelites’ journey to P Canaan, from egypt to the plains of Moab. this parashah, the last in the book of Numbers, concludes with the israelites poised to enter the Promised Land, their long journey finally at an end. t he parashah contains a list of the forty-two places at which the israelites stopped during their wanderings, an itinerary that reminds the israelites of just how far they have come: from slavery, through the trials of the wilderness, and on to the threshold of entering Canaan as a free people in their own land. An account of Aaron’s death interrupts the narrative, reminding the people that the leaders of their journey will not accompany them as they cross the Jordan. the narrative then shifts from a recollection of the journey to God’s directions for how the israelites will occupy and live in the Promised Land. God’s concern is not only with the geographic boundaries of the land, but with the social and legal boundaries that will regulate the interactions of its inhabitants. -

Daf Ditty Pesachim 78: Korban Pesach Today (?)

Daf Ditty Pesachim 78: Korban Pesach today (?) Three girls in Israel were detained by the Israeli Police (2018). The girls are activists of the “Return to the Mount” (Chozrim Lahar) movement. Why were they detained? They had posted Arabic signs in the Muslim Quarter calling upon Muslims to leave the Temple Mount area until Friday night, in order to allow Jews to bring the Korban Pesach. This is the fourth time that activists of the movement will come to the Old City on Erev Pesach with goats that they plan to bring as the Korban Pesach. There is also an organization called the Temple Institute that actively is trying to bring back the Korban Pesach. It is, of course, very controversial and the issues lie at the heart of one of the most fascinating halachic debates in the past two centuries. 1 The previous mishnah was concerned with the offering of the paschal lamb when the people who were to slaughter it and/or eat it were in a state of ritual impurity. Our present mishnah is concerned with a paschal lamb which itself becomes ritually impure. Such a lamb may not be eaten. (However, we learned incidentally in our study of 5:3 that the blood that gushed from the lamb's throat at the moment of slaughter was collected in a bowl by an attendant priest and passed down the line so that it could be sprinkled on the altar). Our mishnah states that if the carcass became ritually defiled, even if the internal organs that were to be burned on the altar were intact and usable the animal was an invalid sacrifice, it could not be served at the Seder and the blood should not be sprinkled. -

Chabad Chodesh Iyar 5781 S������ D��� ��I��� Ceive the Child Inaspecial White Cloth Heprovided

בס“ד Iyar 5781/2021 S D I Volume 32, Issue 2 Nisan 30/April 12/Monday First Day Rosh Chodesh Iyar 1/April 13/Tuesday Second Day Rosh Chodesh Plague of Blood. (Seder Olam, 3) Foundaon laid for Second Beis HaMikdash, 3391 [537 BCE]. (Ezra 3:8) Iyar 2/April 14/Wednesday Birthday of our holy Master and Teacher R. Shmuel, "The Rebbe MaHaRaSh", fourth Chabad Rebbe, on Tiferes SheB’Tiferes of have to go above measure and limit, you go the Omer, 5594 [1834]. “..His life and work “over” —the Rebbe MaHaRaSh said “go over in is best summarized by his saying, “The world the first place”, in a way that’s above calcula- says if you can’t go under an obstacle, you ons and limits.” [Sichah, Tishrei 13, 5739] have to go over, and I say —go over in the first place.” The simple meaning of this is Shlomoh HaMelech began building the First that in Torah and Mitzvos we have to “go Beis HaMikdash, 2928 [833 BCE]. over in the first place”: not make calcula- ons, and when that’s not enough, and you B I ‐ B R M 5594 (1834) Aer the fire in Lubavitch in 5594 (1834), though the Tzemach Tzedek’s house wasn’t burnt, he decided to purchase a large lot and build a house and Beis Medrash. Count Lubomirsky ordered his manager to provide all the wood and had the beams brought to the site and provided the la- bor for free. The Tzemach Tzedek wanted to move in before Shavuos and the Rebbetzin wanted to give birth Chabad Chodesh Iyar 5781 Chabad Chodesh Iyar there. -

Who Gets the Last Word?

מטות- מ ס ע י תשפ"א Mattot-Masei 5781 Who Gets the Last Word? Rabbi Judith Hauptman, E. Billy Ivry Professor Emerita of Talmud and Rabbinic Culture, JTS Mattot and Masei, the last two portions of the book of (Num. 27:7), i.e., these women have a valid claim. They will Numbers (30:2–36:18), are usually read one after the other receive their father’s parcel and his name will not be blotted on the same Sabbath. Are these portions linked by out. something other than the quirks of the Jewish calendar? But in the last chapter of Mattot-Masei, we read a story that Mattot opens with a chapter on the subject of vows. A vow is is a mirror image of the one above. The men of Menasseh, a person’s promise to God to behave in a certain way so that Zelophehad’s tribe, approach Moses and say that his decision God, in response, will grant one’s requests. When Jacob was regarding the five women could redound to the men’s fleeing from Esau, he took a vow that if God protected him detriment. If the women who inherit land in Menasseh’s tract on his journey and returned him home safely, he would give marry a man from a different tribe, they will take their land back to God a tenth of whatever God gave him (Gen. with them. It will thereby diminish Menasseh’s holdings, and 28:22). A vow thus gives a person a sense of control over his that would be unfair. -

Month Ly Newslet

Volume 6, Issue 8 May 2019 Iyar 5779 which together have)ג(, and gimel)ל( Pesach Sheni 2019 is observed on May 19 ters lamed (14 Iyar). the numerical value of 33. “BaOmer” means “of It is customary to mark this day by eating mat- the Omer.” The Omer is the counting period that z a h — if possible — and by omit- begins on the second day of Passover and culmi- ting Tachanun from the prayer services. nates with the holiday of Shavuot, following day 49. How Pesach Sheni Came About Hence Lag BaOmer is the 33rd day of the Omer A year after the Exodus, G‑d instructed the peo- count, which coincides with 18 Iyar. What hap- ple of Israel to bring the Passover offering on the pened on 18 Iyar that’s worth celebrating? afternoon of the fourteenth of Nissan, and to eat it that evening, roasted over the fire, together with What We Are Celebrating matzah and bitter herbs, as they had done the pre- Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, who lived in the sec- vious year just before they left Egypt. ond century of the Common Era, was the first to “There were, however, certain persons who had publicly teach the mystical dimension of become ritually impure through contact with a the Torah known as the Kabbalah, and is the au- dead body, and could not, therefore, prepare the thor of the classic text of Kabbalah, the Zohar. Passover offering on that day. They ap- On the day of his passing, Rab- proached Mosesand Aaron . and they said: bi Shimon instructed his disciples to mark the date ‘. -

BULLETIN Volume 103, Number 6 • June/July 2016 Survivor Scroll #992

WILSHIRE BOULEVARD TEMPLE BULLETIN Volume 103, Number 6 • June/July 2016 Survivor Scroll #992 hen one thinks of the Rabbi Alfred Wolf of Wilshire Boulevard Temple secured WHolocaust and hears Torah #992 on permanent loan. the word survivor, it is a person For the first time ever and in commemoration of Yom that most likely comes to mind. HaShoah, 18 of the Czech scrolls are on display together at the However, people were not the Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust (LAMOTH)—and ours only survivors of this historic is among them. The exhibit features pictures of the institutions’ tragedy: 1,564 Czech Torah representative clergy holding the scrolls, as well as an audio guide scrolls, which were collected with recordings made by the clergy about their respective scrolls. by the Nazis and placed on I was honored to be photographed extermination lists or earmarked and make the recording for for housing in what Adolf Hitler Wilshire Boulevard Temple. Cantor Ettinger standing next called “a museum to an extinct You can view our Czech to his picture at the Los Angeles race,” also endured. Not only did Torah scroll on exhibit at Museum of the Holocaust. these scrolls survive, they live on LAMOTH until Friday, June 10. as testaments to the failure of Hitler’s plan. Scroll #992 will then be returned Thanks to a gallant effort by Westminster Synagogue to us and will go on display in the in London, these scrolls were saved, repaired, and given new Nettie Wolf Gallery on the first life and purpose by being sent to synagogues all over the floor of the Glazer Campus along world (many of which could not afford to purchase their own with photos from the exhibit. -

Chametz and Matzah on Pesach Sheni

בס"ד Volume 8. Issue 23 Chametz and Matzah on Pesach Sheni This week we continue our learning about Pesach except for with it [the korban pesach] in its Sheni. The Mishnah (9:3) discusses the consumption.” The Minchat Chinnuch does not similarities and differences between Pesach and know where the source for the prohibition of Pesach Sheni. With respect to chametz, even eating chametz with the korban pesach would though the korban must also be eaten with come from. Even if one wanted to explain that matzah and marror, there is no prohibition of Rashi was referring to the first kezayit and it was finding or possessing chametz on Pesach Sheni. due to the reshut being mevatel the mitzvah, then We shall look into this point. it would apply to all other foods that were not a mitzvah to eat with the korban pesach! The Minchat Chinnuch (383:3) explains that the pesach, matzah and marror on Pesach Sheni may The footnotes on the Minchat Chinnuch direct us either be eaten together and separately. He to the Meshech Chochma who explains that the continues explaining that there is no prohibition prohibition is not explicit, but rather a prohibition of chametz whatsoever on Pesach Sheni. that is derived from a positive commandment – Consequently, once the first kezayit, the lav ha’ba michlal aseh. The positive instruction is obligatory amount, of the korban pesach is to eat the korban with matzah and marror – “al consumed, the rest may be eaten along with matzot u’marrorim yochluhu” – implying that it chametz. The only reason why the first kezayit should not be eating with chametz. -

AN EXQUISITE MEDIEVAL HAGGADAH An-Exquisite-Medieval-Haggadah

ON VIEW FOR THE FIRST TIME IN 100 YEARS: AN EXQUISITE MEDIEVAL HAGGADAH https://mosaicmagazine.com/observation/arts-culture/2019/04/on-view-for-the-first-time-in-100-years- an-exquisite-medieval-haggadah/ A few months ago, I was approached with a request to become involved in a then- secret mission: to examine one of the very few high-medieval Haggadahs still in private hands. April 23, 2019 | Marc Michael Epstein A few months ago, a highly regarded expert in medieval manuscripts approached me with a request to become involved in a then-secret mission. Sandra Hindman is a scholar who—through her Les Enluminures galleries in Paris, Chicago, and New York —aids and guides libraries, institutions, and private individuals in acquiring some of the best and last-surviving products of medieval illuminators and their workshops. To this end, she has A page from the Lombard Haggadah. Les issued a series of meticulously Enluminures. researched catalogues describing and interpreting such manuscripts. Although it’s unusual for her to devote one of these catalogues to a single manuscript, this one, Hindman felt, was worthy of the attention. Would I have a look? I would indeed. A few days later, my assistant Gabriel Isaacs and I set out for Manhattan’s Upper East Side expecting to be shown a charter, a loan contract, a Bible with some Hebrew glosses or annotations, or perhaps a Book of Hours depicting Jews in particularly vicious caricature. Little could we have guessed what awaited us: one of the very few high-medieval Haggadahs still in private hands, and a supremely fascinating one. -

Pesach for the Year 5780 Times Listed Are for Passaic, NJ Based in Part Upon the Guide Prepared by Rabbi Shmuel Lesches (Yeshivah Shul – Young Yeshivah, Melbourne)

בס״ד Laws and Customs: Pesach For the year 5780 Times listed are for Passaic, NJ Based in part upon the guide prepared by Rabbi Shmuel Lesches (Yeshivah Shul – Young Yeshivah, Melbourne) THIRTY DAYS BEFORE PESACH not to impact one’s Sefiras Haomer. CLEANING AWAY THE [Alert: Polar flight routes can be From Purim onward, one should learn CHAMETZ equally, if not more, problematic. and become fluent in the Halachos of Guidance should be sought from a It is improper to complain about the Pesach. Since an inspiring Pesach is Rav familiar with these matters.] work and effort required in preparing the product of diligent preparation, for Pesach. one should learn Maamarim which MONTH OF NISSAN focus on its inner dimension. Matzah One should remember to clean or Tachnun is not recited the entire is not eaten. However, until the end- discard any Chometz found in the month. Similarly, Av Harachamim and time for eating Chometz on Erev “less obvious” locations such as Tzidkasecha are omitted each Pesach, one may eat Matzah-like vacuum cleaners, brooms, mops, floor Shabbos. crackers which are really Chometz or ducts, kitchen walls, car interiors egg-Matzah. One may also eat Matzah The Nossi is recited each of the first (including rented cars), car-seats, balls or foods containing Matzah twelve days of Nissan, followed by the baby carriages, highchairs (the tray meal. One may also be lenient for Yehi Ratzon printed in the Siddur. It is should also be lined), briefcases, children below the age of Chinuch. recited even by a Kohen and Levi. -

KMS Sefer Minhagim

KMS Sefer Minhagim Kemp Mill Synagogue Silver Spring, Maryland Version 1.60 February 2017 KMS Sefer Minhagim Version 1.60 Table of Contents 1. NOSACH ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 RITE FOR SERVICES ............................................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 RITE FOR SELICHOT ............................................................................................................................................ 1 1.3 NOSACH FOR KADDISH ....................................................................................................................................... 1 1.4 PRONUNCIATION ............................................................................................................................................... 1 1.5 LUACH ............................................................................................................................................................ 1 2. WHO MAY SERVE AS SH’LIACH TZIBUR .......................................................................................................... 2 2.1 SH’LIACH TZIBUR MUST BE APPOINTED .................................................................................................................. 2 2.2 QUALIFICATIONS TO SERVE AS SH’LIACH TZIBUR .....................................................................................................