Passover and the Last Supper, Tyndale Bulletin 53.2 (2002)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Last Supper & the Lord's Supper

These study lessons are for individual or group Bible study and may be freely copied or distributed for class purposes. Please do not modify the material or distribute partially. Under no circumstances are these lessons to be sold. Comments are welcomed and may be emailed to [email protected]. THE LAST SUPPER & THE LORD’S SUPPER Curtis Byers 2008 Leonardo Da Vinci's The Last Supper The Last Supper (in Italian, Il Cenacolo or L'Ultima Cena) is a 15th century mural painting in Milan, created by Leonardo da Vinci for his patron Duke Lodovico Sforza. It represents the scene of The Last Supper from the final days of Jesus as depicted in the Bible. Leonardo da Vinci's painting of the Last Supper is based on John 13:21, where Jesus announced that one of his 12 disciples would betray him. The Last Supper painting is one of the most well known and valued paintings in the world; unlike many other valuable paintings, however, it has never been privately owned because it cannot easily be moved. Leonardo da Vinci's painting of The Last Supper measures 460 x 880 cm (15 feet x 29 feet) and can be found in the refectory of the convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, Italy. The Last Supper specifically portrays the reaction given by each apostle when Jesus said one of them would betray him. All twelve apostles have different reactions to the news, with various degrees of anger and shock. From left to right: Bartholomew, James the Lesser and Andrew form a group of three, all are surprised. -

Thetorah -Com

6t9t2U2U I ne Paraoox oI Pesacn :inenr - | ne I oran.com TheTorah -com The Paradox of Pesach Sheni As a historical commemoration, Passover is tied to a specific date. Nevertheless, the Torah gives a make-up date for bringing the offering a month later. Gerim, non- Israelites living among Israelites as equals, are also allowed to bring this offering, even though it wasn)t their ancestors who were freed. How do we make sense of these anomalies? Prof. Steven Fraade u* ntrs .!i.aitrir! i'irir;ri{,r I t i I I 5* \} - A Fixed Lunar-Calendrical Commemoration: A fter explaining to Moses how the Israelites should perform the Passover I I ritual in order to avoid being killed during the plague of the firstborn, YHWH endswith: El? nll triri nin] T:rr ntDur ExodD:14 This day shallbe to you one of ;r:;r-! rf inx onirrlr firpr5 remembrance: you shall celebrate it as a hltns'//unrnrr thelnrah enm/artinlc/the-naradav-nf-nceanh-ehpni 1 111 6t9t2U2t) I he Paradox ot Pesach shent - | ne loran.com .r;lilT tr?i9 ni?l;| tr)!I-r1' festival to YHWH throughout the ages; you shall celebrate it as an institution for all time. Moses then passes the message along to the elders of Israel, expanding on this point: 'D:r' niDu' Exod'12:2t+ l?:Tn n$ trR"lDt?l You shall observe this as an .o?ip ru Tt;}'r! il4);'rrn institution for all time, for you and for ;'1):r' f':lqt? tli tNff '? i"l';r'l your descendants. -

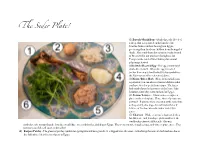

The Seder Plate

Te Seder Plate! (1) Zaroah/Shank Bone - Symbolizes the blood of a sheep that was painted on the lintels of the Israelite homes on their last night in Egypt, protecting their firstborn children from the angel of death. Also symbolizes the sacrifice for the festival of Passover that our ancestors brought to the Temple in the land of Israel during this annual pilgrimage festival. (2)Beitzah/Roasted Egg - The egg is round and symbolizes rebirth. When the egg is roasted (rather than simply hard boiled) it also symbolizes the Passover sacrifice referenced above. (3)Maror/Bitter Herb - Here, horseradish paste is pictured; you can also use horseradish root that you have sliced or peeled into strips. The bitter herb symbolizes the bitterness of the lives of the Israelites when they were enslaved in Egypt. (4) Potato/Lettuce - Often lettuce occupies a place on the seder plate. Here, slices of potato are pictured. If potato, these are eaten at the same time as the parsley, also dipped in salt water (6) or if lettuce, at the time when the bitter herb (3) is eaten. (5) Charoset - While everyone’s charoset looks a bit different - and Jewish people from all over the world make charoset differently - this mix symbolizes the mortar that the Israelites would have used with bricks, building in Egypt. This is often a mix of apples, nuts, and wine or grape juice. This sweetness is a beloved taste of the seder! (6) Karpas/Parsley - The green of parsley symbolizes springtime and new growth. It is dipped into salt water, symbolizing the tears of the Israelites due to the difficulty of their lives in slavery in Egypt.. -

The Death and Resurrection of Jesus the Final Three Chapters Of

Matthew 26-28: The Death and Resurrection of Jesus The final three chapters of Matthew’s gospel follow Mark’s lead in telling of the passion, death and resurrection of Jesus. At each stage Matthew adds to Mark’s story material that addresses concerns of his community. The overall story will be familiar to most readers. We shall focus on the features that are distinctive of Matthew’s version, while keeping the historical situation of Jesus’ condemnation in view. Last Supper, Gethsemane, Arrest and Trial (26:1–75) The story of Jesus’ last day begins with the plot of the priestly leadership to do away with Jesus (26:1–5). As in Mark 14:1-2 they are portrayed as acting with caution, fearing that an execution on the feast of Passover would upset the people (v 5). Like other early Christians, Matthew held the priestly leadership responsible for Jesus’ death and makes a special effort to show that Pilate was a reluctant participant. Matthew’s apologetic concerns probably color this aspect of the narrative. While there was close collaboration between the Jewish priestly elite and the officials of the empire like Pilate, the punishment meted out to Jesus was a distinctly Roman one. His activity, particularly in the Temple when he arrived in Jerusalem, however he understood it, was no doubt perceived as a threat to the political order and it was for such seditious activity that he was executed. Mark (14:3–9) and John (12:1–8) as well as Matthew (26:6–13) report a dramatic story of the anointing of Jesus by a repentant sinful woman, which Jesus interprets as a preparation for his burial (v. -

The Last Supper

Easter | Session 2 | Uptown Good Friday Lesson The Last Supper BIBLE PASSAGE: Matthew 26; John 13 STORY POINT: Jesus and his disciples ate the first Lord’s Supper at Passover. KEY PASSAGE: Romans 10:9 BIG PICTURE QUESTION: Who saves us from our sin? Only Jesus saves us from sin. Activity page Invite kids to complete “The Lord’s Supper” on the activity page. Kids should use the code to reveal two important parts of the Lord’s Supper. (bread, cup) Each box relates to the corresponding letter’s position in the grid. SAY • In the Bible story we will hear today, Jesus ate a special meal with His disciples. The meal was usually to remember the Passover, but Jesus used the bread and the cup to talk about something even greater. Play Dough Meal Provide a lump of play dough for each kid. Invite kids to work together to sculpt items for a dinner. Kids may form cups, plates, flatware, and various foods. As kids work, ask them to describe what they are creating. SAY • Do you ever have a special meal to celebrate a holiday or event? What kinds of foods are served at that meal? Today we are going to hear about a meal Jesus ate with His disciples. We will also learn why believers still celebrate that meal today when we share the Lord’s Supper. The Bible Story Jesus’ disciples went into the city to prepare the Passover meal. When the meal was ready, Jesus and His disciples reclined at the table. Jesus knew His time on earth was almost over and He would soon return to the Father in heaven. -

The Last Supper

The Last Supper Scripture Reference: Luke 22:7-23 Suggested Emphasis: God has always taken care of his people (Old Testament, New Testament, and today). ….. ….. ….. ….. ….. ….. Story Overview: Just as Scripture commanded, Jesus ate the Passover meal. This meal was usually celebrated with family and Jesus ate it with those who were closest to him – his disciples. During this meal the Jews were to remember how God had saved them from Egypt. Background Study: Read the other gospel accounts in Matthew 26:17-25; Mark 14:12-21; and John 13:18-30. The Passover feast was an extremely important yearly event for the Jews. The Jews still celebrate it today. This last Passover meal that Jesus and his disciples celebrated together (the Last Supper) set off the chain of events leading to the crucifixion. Use this lesson to explain the Passover Meal and why they were celebrating it. Introduce the fact that Judas would betray Jesus. Next week continue talking about the meal but then spend time discussing how Jesus gave new meaning to the bread and wine. The new meaning involves remembering his body and blood and is the Lord’s Supper that we celebrate each week. (Leviticus 23:4-8) The Passover lamb was sacrificed at a specific time on the fourteenth day of the first month on the Jewish calendar. (This was the day of the first Passover). In this case it was on Thursday of Passion Week. The first Passover was celebrated hundreds and hundreds of years earlier on the last night that the Jews were captive in Egypt (Exodus 12) . -

Easter the Last Supper (The Lord's Supper) 3/22/20

Easter The Last Supper (The Lord’s Supper) 3/22/20 Scripture Reference: Matthew 26:17-30, Mark 14:12-26, Luke 22:7-30; John 13:1-30 Goals: The children will: • Hear the story of Jesus’ last supper with His disciples. • Learn that we celebrate Easter because of Jesus. • Discover that Jesus wants us to remember Him. Memory Verse: Jesus is risen, as He said. Matthew 28:6 Use the sign language chart to teach the memory verse. Opening Prayer: Dear Jesus, We worship You as our King. We thank You for all the good things you do for us. We love You!! Amen. WORSHIP Songs: (Use sign language from memory verse chart as you sing this song.) Jesus is Risen (tune: “Mary Had a Little Lamb”) Jesus is risen as He said, as He said, as He said. Jesus is risen as He said, Matt-hew 28:6 Clap Your Hands (Tune: “London Bridge” Clap your hands and sing for joy, sing for joy, sing for joy. (Clap hands while singing) Clap your hands and sing for joy. (Clap hands while singing) Christ is risen! (Point a finger up) Now we have good news to tell, news to tell, news to tell! (Cup hands around mouth) Now we have good news to tell! (Cup hands around mouth) Christ is risen! (Point a finger up) Introduction: Remember Do: Show photographs of people. Talk About: When someone is not with us, we can look at pictures and remember how much they loved us and fun things we did together. -

AN EXQUISITE MEDIEVAL HAGGADAH An-Exquisite-Medieval-Haggadah

ON VIEW FOR THE FIRST TIME IN 100 YEARS: AN EXQUISITE MEDIEVAL HAGGADAH https://mosaicmagazine.com/observation/arts-culture/2019/04/on-view-for-the-first-time-in-100-years- an-exquisite-medieval-haggadah/ A few months ago, I was approached with a request to become involved in a then- secret mission: to examine one of the very few high-medieval Haggadahs still in private hands. April 23, 2019 | Marc Michael Epstein A few months ago, a highly regarded expert in medieval manuscripts approached me with a request to become involved in a then-secret mission. Sandra Hindman is a scholar who—through her Les Enluminures galleries in Paris, Chicago, and New York —aids and guides libraries, institutions, and private individuals in acquiring some of the best and last-surviving products of medieval illuminators and their workshops. To this end, she has A page from the Lombard Haggadah. Les issued a series of meticulously Enluminures. researched catalogues describing and interpreting such manuscripts. Although it’s unusual for her to devote one of these catalogues to a single manuscript, this one, Hindman felt, was worthy of the attention. Would I have a look? I would indeed. A few days later, my assistant Gabriel Isaacs and I set out for Manhattan’s Upper East Side expecting to be shown a charter, a loan contract, a Bible with some Hebrew glosses or annotations, or perhaps a Book of Hours depicting Jews in particularly vicious caricature. Little could we have guessed what awaited us: one of the very few high-medieval Haggadahs still in private hands, and a supremely fascinating one. -

The First Joyful Mystery the ANNUNCIATION 1. the Time for the Incarnation Is at Hand. 2. of All Women God Prepared Mary from He

The First Joyful Mystery THE ANNUNCIATION 1. The time for the Incarnation is at hand. 2. Of all women God prepared Mary from her conception to be the Mother of the Incarnate Word. 3. The Angel Gabriel announces: "Hail, full of grace! The Lord is with thee." 4. Mary wonders at this salutation. 5. The Angel assures her: "Fear not . you shall conceive in your womb, and give birth to a Son." 6. Mary is troubled for she has made a vow of virginity. 7. The Angel answers that she will conceive by the power of the Holy Spirit, and her Son will be called the Son of God. 8. The Incarnation awaits Mary's consent. 9. Mary answers: "Behold the handmaid of the Lord. Be it done unto me according to your word." 10. The Word was made flesh and dwelt among us. Spiritual Fruit: Humility The Second Joyful Mystery THE VISITATION 1. Mary's cousin Elizabeth conceived a son in her old age . for nothing is impossible with God. 2. Charity prompts Mary to hasten to visit Elizabeth in the hour of her need. 3. The journey to Elizabeth's home is about eighty miles requiring four or five days. 4. Though long and arduous, the journey is joyous, for Mary bears with her the Incarnate Word. 5. At Mary's salutation, John the Baptist is sanctified in his mother's womb. 6. Elizabeth exclaims: "Blessed are you among women, and blessed is the fruit of your womb." 7. "How have I deserved that the mother of my Lord should come to me?" 8. -

Thursday the Last Supper on This Night We Commemorate Jesus' Meal

Thursday The Last Supper On this night we commemorate Jesus’ meal with his disciples where he says some special words and does some special things. Let’s listen and see. Then came the day of Unleavened Bread, on which the Passover lamb had to be sacrificed. So Jesus sent Peter and John, saying, “Go and prepare the Passover meal for us that we may eat it.” They asked him, “Where do you want us to make preparation for it?” “Listen,” he said to them, “when you have entered the city, a man carrying a jar of water will meet you; follow him into the house he enters and say to the owner of the house ‘The teacher asks you, “Where is the guest room where I may eat the Passover with my disciples?”’ “He will show you a large room upstairs, already furnished. Make preparations for us there.” So, they went and found everything as he had told them; and they prepared the Passover meal. When it was evening he came with the twelve. While they were eating, he took a loaf of bread, and after blessing it he broke it, gave it to them, and said, “Take; this is my body.” Then he took a cup, and after giving thanks he gave it to them, and all of them drank from it. He said to them “This is my blood of the covenant which is poured out for many.” When they had sung a hymn, they went out to the Mount of Olives. I wonder if this table reminds you of anything? Have you seen it at church? What happens at this table? I wonder how the disciples felt when Jesus said those words at supper, take, eat, take, drink? Do they remind us of anything we have heard at church? Every Sunday when we gather the priest says these words of Jesus. -

Part 2 Proofs the Last Supper Was Not the Passover

Part 2 Proofs the Last Supper Was Not the Passover Copyright © 2014, T. Alex Tennent. May not be distributed or copied without publisher’s permission. Brief excerpts may be used in proper context in critical articles, reviews, academic papers, and blogs. Proofs the Last Supper Was Not the Passover The majority of this section covers the various proofs that the Last Supper was not the Passover, with additional information that the ritual of Communion was not something the Messiah or the early believers wanted or taught. The “Template Chal- lenge” forces various beliefs to logically lay out certain scriptural events with the Jewish template of the Passover feast. Then the “Three Keys” chapter takes those scriptures that seem to so clearly have Jesus eating the Passover at the Last Supper and shows what they actually mean in the original Greek. This is followed by the “Fifty Reasons” chapter, which attempts to group all the proofs that the Last Supper was not the Passover into a single chapter. “Between the Evenings” explores various Jewish laws and idioms that show the proper time and day to slay the Passover, which are vital in disproving several false theories. Other important truths are also seen in this chapter. And finally we take a close look at whether the scriptures actually teach a ritual of Communion in the chapter “The Ritual—Why Didn’t the Jewish Disciples Teach It?” Copyright © 2014, T. Alex Tennent. May not be distributed or copied without publisher’s permission. Brief excerpts may be used in proper context in critical articles, reviews, academic papers, and blogs. -

Shabbos Chol Hamoed Pesach When Eating Is a Mitzvah

ב''ה SERMON RESOURCE FOR SHLUCHIM שבת חול - המועד פסח /SHABBOS CHOL HAMOED PESACH WHEN EATING IS A MITZVAH DISTRIBUTION DATE: י"א ניסן תשס"ט / TUESDAY APRIL 5, 2009 PARSHA: שבת חול - המועד פסח /SHABBOS CHOL HAMOED PESACH SERMON TITLE: WHEN EATING IS A MITZVAH Sponsored by Shimon Aron & Devorah Leah Rosenfeld & Family A PROJECT OF THE SHLUCHIM OFFICE In loving memory of 1 ר' מנחם זאב בן פנחס ז''ל Emil W. Herman Z י"א ניסן תשס"ט • DISTRIBUTION DATE: TUESDAY APRIL 5, 2009 The author is solely responsible for the contents of this document. who loved and supported Torah learning. ב''ה SERMON RESOURCE FOR SHLUCHIM שבת חול - המועד פסח /SHABBOS CHOL HAMOED PESACH WHEN EATING IS A MITZVAH שבת חול - המועד פסח /SHABBOS CHOL HAMOED PESACH WHEN EATING IS A MITZVAH A stranger stranded in a Jewish home who tries to learn about Jewish life will come to the conclusion that out of the 613 mitzvos, at least 600 of them have to do with food. On Shabbos, for example, the Jews are constantly busy with food, whether gefilte fish, chicken soup or cholent. Any Jewish holiday, when you think about it, has its own special food, whether hamantashen on Purim, latkes on Chanukah, kreplach before Yom Kippur or kneidlach on Passover—everything revolves around food. But when you really look at Jewish holidays you realize that every holiday has a mitzvah that makes it unique: Rosh Hashanah has the shofar, Chanukah has the menorah, Sukkos has the sukkah, and Purim has the megillah. Each one has its own Jewish ritual.