Euthanasia of Experimental Animals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Standard Operating Procedure

Biomedical Research Support Facility Standard Operating Procedure Euthanasia by Cervical Dislocation The IACUC is specifically charged with reviewing the methods of euthanasia for each research protocol to assure compliance with the recommendations contained in the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals (2013 Edition) http://www.avma.org/issues/animal_welfare/euthanasia.pdf. Since physical methods of euthanasia (such as cervical dislocation) require the most skill to perform and are most likely to be affected by human error, the AVMA recommends that such methods be used only when pharmacological methods are not appropriate. Cervical dislocation (CD) is rapid, requires neither special equipment nor transport of the animal and yields tissues uncontaminated by chemical agents. Situations where CD may be indicated in non-sedated rodents include research studies which require the harvest of drug residue- free brain tissues. The use of CD as a euthanasia method and the names of the individuals performing this procedure must be listed in the approved IACUC protocol covering the study. Acceptable Use The use of cervical dislocation in rodents is only appropriate for mice and small rats (<200g), and whenever possible the use of sedation or light anesthesia prior to euthanasia is recommended. The protocol must contain adequate scientific justification if CD must be performed on conscious animals due to study requirements. CD may also be used as a secondary means to assure death after euthanasia with CO2 or another gaseous euthanasia agent. Training Cervical dislocation (CD) euthanasia must be performed by trained individuals using appropriate equipment. The IACUC reviews all protocols using physical euthanasia techniques to assure that personnel performing the procedures are appropriately trained. -

Use of Tribromoethanol (Avertin)”

Washington State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee Policy #32 “Use of Tribromoethanol (Avertin)” Approval Date: 11/18/2019 (Replacing Version: 11/16/2016) A. Purpose To provide guidance on the use of tribromoethanol (TBE) in animal studies and to provide standardized methods for its preparation and storage. B. Background In compliance with federal Animal Welfare Regulations and guidance from regulatory and oversight bodies, the IACUC expects that investigators use pharmaceutical grade medications whenever they are available, even in acute-terminal procedures.1,2 Non- pharmaceutical grade compounds should only be used after specific review and approval by the IACUC for reasons such as scientific necessity, or non-availability of an acceptable veterinary or human pharmaceutical-grade product. Cost savings is not adequate justification for using non-pharmaceutical grade compounds in research animals (see WSU IACUC Policy #29, Use of Non-Pharmaceutical Grade Substances in Laboratory Animals). Tribromoethanol (TBE) is an injectable anesthetic previously manufactured under the trade name Avertin®; however, this product is no longer available in pharmaceutical grade. In addition, TBE can cause a number of deleterious effects when administered to animals2-8: • TBE degrades in the presence of heat or light to produce the toxic byproducts, dibromoacetaldehyde and hydrobromic acid, which are nephrotoxic and hepatotoxic. • Administration of degraded TBE solutions has been associated with post- anesthetic illness and death, often within 24 hours of injection. 1 • Peritonitis abdominal adhesions and ileus (reduced gut motility) leading to death of the animal can occur following intraperitoneal (IP) administration of TBE. • Other side effects include muscle necrosis, hepatic damage, bacterial translocation, sepsis, and serositis of abdominal organs. -

Cyclopropane Anaesthesia by JOHN BOYD, M.D., D.A

Cyclopropane Anaesthesia By JOHN BOYD, M.D., D.A. TLHIS paper is based on my experience of one thousand cases of cyclopropane anaesthesia personally conducted by me since October, 1938, both in hospital and in private. But before discussing these it might be convenient for me to mention here something about the drug itself. HISTORY. Cyclopropane was first isolated in Germany in 1882 by Freund, who also demonstrated its chemical structure, C3H6. He did not, however, describe its anaesthetic properties. Following its discovery it seems to have been forgotten until 1928, when Henderson and Lucas of Toronto, in investigating contaminants of propylene, another anesthetic with undesirable side-effects, and itself'an isomer of cyclopropane, found that the supposed cause of the cardiac disturbances was in reality a better and less toxic anaesthetic. They demonstrated its anaesthetic properties first on animals, and then, before releasing it to the medical profession for clinical trial, they anaesthetised each other, and determined the quantities necessary for administration to man. In 1933 the first clinical trials of cyclopropane were made by Waters and his associates of the University of Wisconsin. In October of that year Waters presented a preliminary report on its anaesthetic properties in man,1 confirming the findings of Henderson and Lucas. Rowbotham introduced it to England first in 1935, and since then its use has spread rapidly throughout the country. PREPARATION. Cyclopropane is prepared commercially by the reduction of trimethylene bromide in the presence of metallic zinc in ethyl alcohol. It is also made commercially from propane in natural gas by progressive thermal chlorination. -

Guidelines for Use of Tribromoethanol in Rodents

Guidelines for Use of Tribromoethanol in Rodents The expectation is that IACUC Guidelines will be followed as best practice. They allow the Animal Care & Use Program to attain acceptable performance outcomes to meet the intent of the regulations. As such, any planned variation from the guidelines requires prior IACUC approval and must be based on a scientific rationale. Introduction Tribromoethanol (TBE) is a popular injectable anesthetic agent used in rodents. It was once manufactured specifically for use as an anesthetic by Winthrop Laboratories under the trade name Avertin®, but this product is no longer available. Currently, it is only available as a non-pharmaceutical- grade powder that must be aseptically reconstituted for injection. When used properly, it has a good margin of safety and it is still popular for certain research applications. TBE is considered a non-pharmaceutical grade drug and as such its use must be in accord with these guidelines and the UGA IACUC Policy on the Use of Outdated Drugs and Materials, Non-pharmaceutical Grade Drugs, and Controlled Substances. The PI is also required to provide information regarding scientific necessity and must take into account the following when proposing the use of this agent in rodents: According to a recent review (Lab Animal 34(10):47-52) tribromoethanol has been associated with serious post-anesthetic effects and inconsistent and variable anesthetic effects. Have these effects been observed by your laboratory? Have alternative anesthetics for this procedure been considered? If so, why has TBE been chosen over these alternatives? Contact your attending veterinarian for consultation on the use of anesthetics. -

Analgesia and Sedation in Hospitalized Children

Analgesia and Sedation in Hospitalized Children By Elizabeth J. Beckman, Pharm.D., BCPS, BCCCP, BCPPS Reviewed by Julie Pingel, Pharm.D., BCPPS; and Brent A. Hall, Pharm.D., BCPPS LEARNING OBJECTIVES 1. Evaluate analgesics and sedative agents on the basis of drug mechanism of action, pharmacokinetic principles, adverse drug reactions, and administration considerations. 2. Design an evidence-based analgesic and/or sedative treatment and monitoring plan for the hospitalized child who is postoperative, acutely ill, or in need of prolonged sedation. 3. Design an analgesic and sedation treatment and monitoring plan to minimize hyperalgesia and delirium and optimize neurodevelopmental outcomes in children. INTRODUCTION ABBREVIATIONS IN THIS CHAPTER Pain, anxiety, fear, distress, and agitation are often experienced by GABA γ-Aminobutyric acid children undergoing medical treatment. Contributory factors may ICP Intracranial pressure include separation from parents, unfamiliar surroundings, sleep dis- PAD Pain, agitation, and delirium turbance, and invasive procedures. Children receive analgesia and PCA Patient-controlled analgesia sedatives to promote comfort, create a safe environment for patient PICU Pediatric ICU and caregiver, and increase patient tolerance to medical interven- PRIS Propofol-related infusion tions such as intravenous access placement or synchrony with syndrome mechanical ventilation. However, using these agents is not without Table of other common abbreviations. risk. Many of the agents used for analgesia and sedation are con- sidered high alert by the Institute for Safe Medication Practices because of their potential to cause significant patient harm, given their adverse effects and the development of tolerance, dependence, and withdrawal symptoms. Added layers of complexity include the ontogeny of the pediatric patient, ongoing disease processes, and presence of organ failure, which may alter the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of these medications. -

Unnamed Document

Mutations M287L and Q266I in the Glycine Receptor ␣1 Subunit Change Sensitivity to Volatile Anesthetics in Oocytes and Neurons, but Not the Minimal Alveolar Concentration in Knockin Mice Cecilia M. Borghese, Ph.D.,* Wei Xiong, Ph.D.,† S. Irene Oh, B.S.,‡ Angel Ho, B.S.,§ S. John Mihic, Ph.D.,ʈ Li Zhang, M.D.,# David M. Lovinger, Ph.D.,** Gregg E. Homanics, Ph.D.,†† Edmond I. Eger 2nd, M.D.,‡‡ R. Adron Harris, Ph.D.§§ ABSTRACT What We Already Know about This Topic • Inhibitory spinal glycine receptor function is enhanced by vol- Background: Volatile anesthetics (VAs) alter the function of atile anesthetics, making this a leading candidate for their key central nervous system proteins but it is not clear which, immobilizing effect if any, of these targets mediates the immobility produced by • Point mutations in the ␣1 subunit of glycine receptors have been identified that increase or decrease receptor potentiation VAs in the face of noxious stimulation. A leading candidate is by volatile anesthetics the glycine receptor, a ligand-gated ion channel important for spinal physiology. VAs variously enhance such function, and blockade of spinal glycine receptors with strychnine af- fects the minimal alveolar concentration (an anesthetic What This Article Tells Us That Is New EC50) in proportion to the degree of enhancement. • Mice harboring specific mutations in their glycine receptors Methods: We produced single amino acid mutations into that increased or decreased potentiation by volatile anesthetic in vitro did not have significantly altered changes in anesthetic the glycine receptor ␣1 subunit that increased (M287L, third potency in vivo transmembrane region) or decreased (Q266I, second trans- • These findings indicate that this glycine receptor does not me- membrane region) sensitivity to isoflurane in recombinant diate anesthetic immobility, and that other targets must be receptors, and introduced such receptors into mice. -

Management of Chronic Problems

MANAGEMENT OF CHRONIC PROBLEMS INTERACTIONS BETWEEN ALCOHOL AND DRUGS A. Leary,* T. MacDonald† SUMMARY concerned. Alcohol may alter the effects of the drug; drug In western society alcohol consumption is common as is may change the effects of alcohol; or both may occur. the use of therapeutic drugs. It is not surprising therefore The interaction between alcohol and drug may be that concomitant use of these should occur frequently. The pharmacokinetic, with altered absorption, metabolism or consequences of this combination vary with the dose of elimination of the drug, alcohol or both.2 Alcohol may drug, the amount of alcohol taken, the mode of affect drug pharmacokinetics by altering gastric emptying administration and the pharmacological effects of the drug or liver metabolism. Drugs may affect alcohol kinetics by concerned. Interactions may be pharmacokinetic or altering gastric emptying or inhibiting gastric alcohol pharmacodynamic, and while coincidental use of alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH).3 This may lead to altered tissue may affect the metabolism or action of a drug, a drug may concentrations of one or both agents, with resultant toxicity. equally affect the metabolism or action of alcohol. Alcohol- The results of concomitant use may also be principally drug interactions may differ with acute and chronic alcohol pharmacodynamic, with combined alcohol and drug effects ingestion, particularly where toxicity is due to a metabolite occurring at the receptor level without important changes rather than the parent drug. There is both inter- and intra- in plasma concentration of either. Some interactions have individual variation in the response to concomitant drug both kinetic and dynamic components and, where this is and alcohol use. -

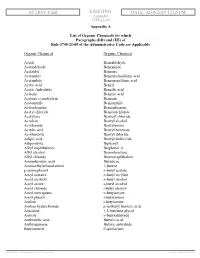

02/06/2019 12:05 PM Appendix 3745-21-09 Appendix A

ACTION: Final EXISTING DATE: 02/06/2019 12:05 PM Appendix 3745-21-09 Appendix A List of Organic Chemicals for which Paragraphs (DD) and (EE) of Rule 3745-21-09 of the Administrative Code are Applicable Organic Chemical Organic Chemical Acetal Benzaldehyde Acetaldehyde Benzamide Acetaldol Benzene Acetamide Benzenedisulfonic acid Acetanilide Benzenesulfonic acid Acetic acid Benzil Acetic Anhydride Benzilic acid Acetone Benzoic acid Acetone cyanohydrin Benzoin Acetonitrile Benzonitrile Acetophenone Benzophenone Acetyl chloride Benzotrichloride Acetylene Benzoyl chloride Acrolein Benzyl alcohol Acrylamide Benzylamine Acrylic acid Benzyl benzoate Acrylonitrile Benzyl chloride Adipic acid Benzyl dichloride Adiponitrile Biphenyl Alkyl naphthalenes Bisphenol A Allyl alcohol Bromobenzene Allyl chloride Bromonaphthalene Aminobenzoic acid Butadiene Aminoethylethanolamine 1-butene p-aminophenol n-butyl acetate Amyl acetates n-butyl acrylate Amyl alcohols n-butyl alcohol Amyl amine s-butyl alcohol Amyl chloride t-butyl alcohol Amyl mercaptans n-butylamine Amyl phenol s-butylamine Aniline t-butylamine Aniline hydrochloride p-tertbutyl benzoic acid Anisidine 1,3-butylene glycol Anisole n-butyraldehyde Anthranilic acid Butyric acid Anthraquinone Butyric anhydride Butyronitrile Caprolactam APPENDIX p(183930) pa(324943) d: (715700) ra(553210) print date: 02/06/2019 12:05 PM 3745-21-09, Appendix A 2 Carbon disulfide Cyclohexene Carbon tetrabromide Cyclohexylamine Carbon tetrachloride Cyclooctadiene Cellulose acetate Decanol Chloroacetic acid Diacetone alcohol -

Fatal Basilar Artery Occlusion Following Cervical Spine Injury

Paraplegia 17 (1979-80) 280-283 FATAL BASILAR ARTERY OCCLUSION FOLLOWING CERVICAL SPINE INJURY By ROBERT M. WOOLSEY, M.D. and HYUNG D. CHUNG, M.D. Spinal Cord Injury Service, St Louis Veterans Administration Medical Center and The Department of Neurology and Neuropathology of St. Louis University St Louis, Missouri 63I25, U.S.A. DESPITE the intimate relationship between the cervical spine and vertebral artery, symptoms referable to vertebral artery damage have rarely been reported in association with cervical spine fractures. The following case of fatal basilar artery occlusion in a patient with vertebral artery thrombosis at the site of a cervical spine fracture is somewhat unique. Case Report A 31-year-old man was injured in an automobile accident on 2715178. When examined shortly thereafter, he was found to have no sensation or movement in his lower extremities. He had intact pain sensation in his right thumb and index finger and along the lateral aspect of his arm and forearm but loss of pain sensation in his other fingers and the medial aspect of his arm and forearm. He was able to flex his right arm and abduct his right shoulder with normal strength. He could extend his right wrist with about 25 per cent normal strength. The remaining muscles of the right arm were paralysed. The left arm was completely immobile, cold and without arterial pulses. Cervical spine X-rays were 'normal'. X-rays of the chest showed fractures involving the second, fourth and fifth ribs, the clavicle and scapula on the left side. There was haziness of the left upper lobe of the lung. -

Backyard Farming and Slaughtering 2 Keeping Tradition Safe

Backyard farming and slaughtering 2 Keeping tradition safe FOOD SAFETY TECHNICAL TOOLKIT FOR ASIA AND THE PACIFIC Backyard farming and slaughtering – Keeping tradition safe Backyard farming and slaughtering 2 Keeping tradition safe FOOD SAFETY TECHNICAL TOOLKIT FOR ASIA AND THE PACIFIC Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Bangkok, 2021 FAO. 2021. Backyard farming and slaughtering – Keeping tradition safe. Food safety technical toolkit for Asia and the Pacific No. 2. Bangkok. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. © FAO, 2021 Some rights reserved. This work is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO license (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this license, this work may be copied, redistributed and adapted for non- commercial purposes, provided that the work is appropriately cited. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that FAO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the FAO logo is not permitted. -

ANIMAL SACRIFICE in ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIAN RELIGION The

CHAPTER FOURTEEN ANIMAL SACRIFICE IN ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIAN RELIGION JOANN SCURLOCK The relationship between men and gods in ancient Mesopotamia was cemented by regular offerings and occasional sacrifices of ani mals. In addition, there were divinatory sacrifices, treaty sacrifices, and even "covenant" sacrifices. The dead, too, were entitled to a form of sacrifice. What follows is intended as a broad survey of ancient Mesopotamian practices across the spectrum, not as an essay on the developments that must have occurred over the course of several millennia of history, nor as a comparative study of regional differences. REGULAR OFFERINGS I Ancient Mesopotamian deities expected to be fed twice a day with out fail by their human worshipers.2 As befitted divine rulers, they also expected a steady diet of meat. Nebuchadnezzar II boasts that he increased the offerings for his gods to new levels of conspicuous consumption. Under his new scheme, Marduk and $arpanitum were to receive on their table "every day" one fattened ungelded bull, fine long fleeced sheep (which they shared with the other gods of Baby1on),3 fish, birds,4 bandicoot rats (Englund 1995: 37-55; cf. I On sacrifices in general, see especially Dhorme (1910: 264-77) and Saggs (1962: 335-38). 2 So too the god of the Israelites (Anderson 1992: 878). For specific biblical refer ences to offerings as "food" for God, see Blome (1934: 13). To the term tamid, used of this daily offering in Rabbinic sources, compare the ancient Mesopotamian offering term gimi "continual." 3 Note that, in the case of gods living in the same temple, this sharing could be literal. -

Cyclobutane Derivatives in Drug Discovery

Cyclobutane Derivatives in Drug Discovery Overview Key Points Unlike larger and conformationally flexible cycloalkanes, Cyclobutane adopts a rigid cyclobutane and cyclopropane have rigid conformations. Due to the ring strain, cyclobutane adopts a rigid puckered puckered conformation Offer ing advantages on (~30°) conformation. This unique architecture bestowed potency, selectivity and certain cyclobutane-containing drugs with unique pharmacokinetic (PK) properties. When applied appropriately, cyclobutyl profile. scaffolds may offer advantages on potency, selectivity and pharmacokinetic (PK) profile. Bridging Molecules for Innovative Medicines 1 PharmaBlock designs and Cyclobutane-containing Drugs synthesizes over 1846 At least four cyclobutane-containing drugs are currently on the market. cyclobutanes, and 497 Chemotherapy carboplatin (Paraplatin, 1) for treating ovarian cancer was cyclobutane products are prepared to lower the strong nephrotoxicity associated with cisplatin. By in stock. CLICK HERE to replacing cisplatin’s two chlorine atoms with cyclobutane-1,1-dicarboxylic find detailed product acid, carboplatin (1) has a much lower nephrotoxicity than cisplatin. On information on webpage. the other hand, Schering-Plough/Merck’s hepatitis C virus (HCV) NS3/4A protease inhibitor boceprevir (Victrelis, 2) also contains a cyclobutane group in its P1 region. It is 3- and 19-fold more potent than the 1 corresponding cyclopropyl and cyclopentyl analogues, respectively. Androgen receptor (AR) antagonist apalutamide (Erleada, 4) for treating castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) has a spirocyclic cyclobutane scaffold. It is in the same series as enzalutamide (Xtandi, 3) discovered by Jung’s group at UCLA in the 2000s. The cyclobutyl- (4) and cyclopentyl- derivative have activities comparable to the dimethyl analogue although the corresponding six-, seven-, and eight-membered rings are slightly less 2 active.