CHILD SACRIFICE & SNAKES the Fragments to Be Discussed in This

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Killing Us Softly 4 Advertising’S Image of Women

MEDIA EDUCATION FOUNDATION STUDY GUIDE Killing Us Softly 4 Advertising’s Image of Women Study Guide by Kendra Hodgson Edited by Jeremy Earp and Jason Young 2 CONTENTS Note to Educators 3 Program Overview 3 Pre-viewing Questions for Discussion & Writing 4 Key Points 5 Post-viewing Questions for Discussion & Writing 9 Assignments 11 Semester-Long Project 14 For additional assignments, please download the Killing Us Softly 3 study guide: http://www.mediaed.org/assets/products/206/studyguide_206.pdf For handouts associated with the Killing Us Softly 3 study guide, also download: http://www.mediaed.org/assets/products/206/studyguidehandout_206.pdf © The Media Education Foundation | www.mediaed.org 3 NOTE TO EDUCATORS This study guide is designed to help you and your students engage and manage the information presented in this video. Given that it can be difficult to teach visual content – and difficult for students to recall detailed information from videos after viewing them – the intention here is to give you a tool to help your students slow down and deepen their thinking about the specific issues this video addresses. With this in mind, we’ve structured the guide to help you stay close to the video’s main line of argument as it unfolds: Key Points provide a concise and comprehensive summary of the video. They are designed to make it easier for you and your students to recall the details of the video during class discussions, and as a reference point for students as they work on assignments. Questions for Discussion & Writing encourage students to reflect critically on the video during class discussions, and guide their written reactions before and after these discussions. -

The Perfect Sacrifice Lesson Focus | Since His Beginning, Man Has Always Offered Sacrifices to God in Order to Atone for His Sins

St. Mary's At-Home Guide - February 24 (Ch 20-21) - Grade 5 Lesson 20 The Perfect Sacrifice Lesson Focus | Since his beginning, man has always offered sacrifices to God in order to atone for his sins. No sacrifice, however, could truly atone for sin because no sacrifice was perfect. Jesus’ offering of himself on the Cross, however, was. That’s because Jesus, who both offered the sacrifice and was the sacrifice, was perfect. At every Mass, Jesus, through the priest, continues to offer himself to God when the bread and wine are transformed into his Body and Blood. It is the same sacrifice offered on Calvary, re–presented in time. 1 | begin Pray the Glory Be with your child. Show your child pictures of sheep, goats, calves, doves, wheat, and wine. Explain that if you had lived in Jerusalem during Jesus’ time, your family would have gone to the temple to give these items to the priest for sacrifice. Together read John 1:19–30 aloud. 2 | summarize Summarize this week’s lesson for your child: Example: When Jesus offered his life on the Cross, he became the one, perfect sacrifice, the Lamb of God offered up for all the world’s sins. After that, it was no longer necessary for people to offer up other ritual sacrifices, such as goats, lambs, and doves. 3 | review References Review this week’s lesson by asking your child the following questions: Student Textbook: 1. What is a sacrifice? (The offering up of something to God.) Chapter 20, pp. 83–86 2. -

From Address to the Second National Congress of Venezuela

from A DDRESS TO THE SECOND NATIONAL CONGRESS OF VENEZUELA 1819 Simón Bolívar Venezuela declared its independence from Spain in 1811, but then had to fight to win it. The war against Spain lasted for ten long years. During this time Venezuela struggled to create its own government. The following excerpt comes from a speech by Simón Bolívar, the great military and political hero of South American liberation. Bolívar argues that Venezuela must shape a government suited to its own special nature, rather than mimic the United States government. THINK THROUGH HISTORY: Recognizing Bias What was Bolívar’s viewpoint toward the majority of the people of Latin America? Why does he caution against a government of too much freedom and responsibility? Subject to the threefold yoke of ignorance, tyranny, and vice, the American peo- ple1 have been unable to acquire knowledge, power, or [civic] virtue. The lessons we received and the models we studied, as pupils of such pernicious teachers, were most destructive. We have been ruled more by deceit than by force, and we have been degraded more by vice than by superstition. Slavery is the daughter of Darkness: an ignorant people is a blind instrument of its own destruction. Ambition and intrigue abuse the credulity and experience of men lacking all politi- cal, economic, and civic knowledge; they adopt pure illusion as reality; they take license for liberty, treachery for patriotism, and vengeance for justice. This situa- tion is similar to that of the robust blind man who, beguiled by his strength, strides forward with all the assurance of one who can see, but, upon hitting every variety of obstacle, finds himself unable to retrace his steps. -

College Comeback: ODHE Formal Guidance

College Comeback A Summary of Ohio Law and Policy on Outstanding Student Balances Owed and Debt-Forgiveness Models that Can Be Applied in Ohio Approximately 1.5 million Ohioans have some college, but no degree (or credential). This presents a critical challenge to maximizing the economic opportunity for that individual as well as for the greater good of the State of Ohio’s economy. These students enrolled in post-secondary education seeking a degree, but we didn’t get them across the finish line. If we successfully help Ohioans enjoy a “college comeback” resulting in a degree (or credential), we can make significant strides toward increasing Ohio’s educational attainment, improving expected gross domestic product, average wages, employment rate and Ohio’s economy. Among the barriers to a college comeback for this population are past-due debts owed to institutions of higher education at which they were previously enrolled, nearly always resulting in an inability to receive a transcript to complete college elsewhere. Facing these barriers, many students opt never to return and complete their degree. In recent years, some institutions of higher education – notably Cleveland State University, Clark State College, Lorain County Community College, Stark State College, and Zane State College right here in Ohio – have begun to offer new debt forgiveness programs. Cleveland State is currently offering up to $5,000 in debt forgiveness – among the best offers we’ve seen nationally. Lorain and Clark State are both offering up to $1,000 in debt relief. A national example is Wayne State University in Detroit. The “Warrior Way Back” program forgives up to $1,500. -

Between Belief and Delusion: Cult Members and the Insanity Plea

REGULAR ARTICLE Between Belief and Delusion: Cult Members and the Insanity Plea Brian Holoyda, MD, MPH, and William Newman, MD Cults are charismatic groups defined by members’ adherence to a set of beliefs and teachings that differ from those of mainstream religions. Cult beliefs may appear unusual or bizarre to those outside of the organization, which can make it difficult for an outsider to know whether a belief is cult-related or delusional. In accordance with these beliefs, or at the behest of a charismatic leader, some cult members may participate in violent crimes such as murder and later attempt to plead not guilty by reason of insanity (NGRI). It is therefore necessary for forensic experts who evaluate cult members to understand how the court has responded to such individuals and their beliefs when they mount a defense of NGRI for murder. Based on a review of extant appellate court case law, cult member defendants have not yet successfully pleaded NGRI on the basis of cult involvement, despite receiving a broad array of psychiatric diagnoses that could qualify for such a defense. With the reintroduction of cult involvement in the DSM-5 criteria for other specified dissociative disorder, however, there may be a resurgence of dissociative-type diagnoses in future cult-related cases, both criminal and civil. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 44:53–62, 2016 Cults are generally considered to be new charismatic organization. Because of this perception, it can be groups that espouse religious doctrine that differs difficult for an outsider to know whether a belief is from mainstream beliefs. -

Student Code of Conduct 2018-2019

STRENGTH OF CHARACTER AND COLLEGE OR CAREER READY STUDENT CODE OF CONDUCT Student Rights, Responsibilities and Character Development VISION Each student demonstrates strength of character and is college or career ready. MISSION The Bibb County School District will develop a highly trained staff and an engaged community dedicated to educating each student for a 21st century global society. 2018-2019 STRENGTH OF CHARACTER AND COLLEGE OR CAREER READY Dear Students and Parents: Welcome to the 2018-2019 school year! One of the main comments I hear from parents is that they want to know that their children are safe when they send them to school each day. Students want to attend school in a secure environment without fear of bullying or violence. It is my belief that every student deserves to benefit from the numerous and diverse educational opportunities offered by the Bibb County School District in a safe learning environment. As you read through this Code of Conduct, you will see evidence the BCSD is committed to fostering a healthy, safe and supportive learning environment conducive to the growth and development of every student. From a focus on safety and security in our district’s Strategic Plan, to the implementation of initiatives such as Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) and The Leader in Me that support strength of character, our district is striving to ensure that positive learning experiences are occurring in each of our schools. The BCSD’s Code of Conduct provides the guidelines that foster the development of our students into successful members of our communities. -

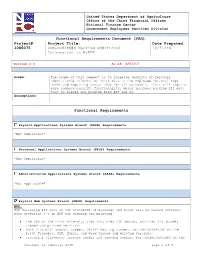

Functional Requirements Document (FRD) Project# Project Title: Date Prepared: 1086075 PPS-CR#29689 Masking Additional 10/31/16 Information in Myepp

United States Department of Agriculture Office of the Chief Financial Officer National Finance Center Government Employees Services Division Functional Requirements Document (FRD) Project# Project Title: Date Prepared: 1086075 PPS-CR#29689 Masking Additional 10/31/16 Information in MyEPP Version 2.0 As of: 3/07/17 Scope: The scope of this request is to increase security of Personal Identifiable Information (PII) data in the Employee Personal Page (EPP) and Reporting Center (RC) for all customers. This will require more complex security functionality, which includes masking PII data that is viewed and printed from EPP and RC. Assumptions: Functional Requirements Payroll Applications Systems Branch (PASB) Requirements “Not Applicable” Personnel Applications Systems Branch (PESB) Requirements “Not Applicable” Administrative Applications Systems Branch (AASB) Requirements “Not Applicable” Payroll Web Systems Branch (PWSB) Requirements EPP: The following PII data on the Statement of Earnings and Leave will be masked entirely with asterisks (*) in EPP for viewing and printing: The SSN on the Print Friendly, View PDF, View DOC (Word), and View Xls (Excel) viewed and printed versions. Bank financial account number, DD/EFT Routing numbers for CHKING/SAVING on the Print Friendly, PDF, Excel, and Word viewed and printed versions. Financial allotments account number and routing numbers for CHKING/SAVINGS on the Version: 11 February 2015 Page 1 of 5 Functional Requirements Document (FRD) Project# Project Title: Date Prepared: 1086075 PPS-CR#29689 Masking Additional Information in 10/31/16 MyEPP Print Friendly, PDF, Excel, and Word viewed and printed versions. Discretionary allotments account number and routing numbers for CHKING/SAVINGS on the Print Friendly, PDF, Excel, and Word viewed and printed versions. -

The Techniques of the Sacrifice

Andm Univcrdy Seminary Stndics, Vol. 44, No. 1,13-49. Copyright 43 2006 Andrews University Press. THE TECHNIQUES OF THE SACRIFICE OF ANIMALS IN ANCIENT ISRAEL AND ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA: NEW INSIGHTS THROUGH COMPARISON, PART 1' JOANNSCURLOCK ELMHURSTCOLLEGE Elmhurst, Illinois There is an understandable desire among followers of religions that are monotheistic and that claim descent from ancient Israelite religion to see that religion as unique and completely at odds with its surroundrng polytheistic competitors. Most would not deny that there are at least a few elements of Israelite religion that are paralleled in neighboring cultures, as, e.g., the Hittites: 'I would like to thank the following persons who read and commented on earlier drafts of this article: R. Bed, M. Hilgert, S. Holloway, R. Jas, B. Levine and M. Murrin. Abbreviations follow those given in W. von Soden, AWches Han&rterbuch, 3 301s. (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1965-1981); and M. Jursa and M. Weszeli, "Register Assyriologie," AfO 40-41 (1993/94): 343-369, with the exception of the following: (a) series: D. 0.Edzard, Gnda and His Dynarg, Royal Inscriptions of Mesopommia: Early Periods (RIME) 311 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997); S. Parpola and K. Watanabe, Neo-Assyrin Treatzes and Lq&y Oaths, State Archives of Assyria (SAA) 2 (Helsinki: Helsinki University Press, 1988); A. Livingstone, Court Poety and Literq Misceubnea, SAA 3 (Helsinki Helsinki University Press, 1989); I. Starr,QnerieJ to the Sungod, SAA 4 (Helsinki Helsinki University Press, 1990); T. Kwasrnan and S. Parpola, Lga/ Trama~~lom$the RoyaiCoz& ofNineveh, Part 1, SAA 6 (Helsinki Helsinki University Press, 1991); F. -

“On the Third Day”: the Time Frame of Jesus' Death And

JETS 56/3 (2013) 511–42 “ON THE THIRD DAY”: THE TIME FRAME OF JESUS’ DEATH AND RESURRECTION MARTIN PICKUP* I. INTRODUCTION The three-day time frame of Jesus’ death and resurrection was a part of the earliest Christian preaching. It had a place in the kerygmatic formula that Paul quotes in 1 Cor 15:3–5, a four-line formula that is generally acknowledged to have originated in the very earliest years of the Church.1 For I delivered to you as of first importance what I also received, that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures, and that He was buried, and that He was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures, and that He appeared to Cephas, then to the twelve.2 * Editor’s note: Martin Pickup unexpectedly passed away shortly after submitting this piece for pub- lication. This article reflects his interest and expertise in the Jewish background to the NT and in the early church’s proclamation of the bodily resurrection of Jesus. His family, friends, and many former students rejoice in the hope Marty defended with such skill in this article. “So also in Christ shall all be made alive” (1 Cor 15:22). 1 Scholars across the theological spectrum acknowledge the earliness of this formula. Most assign it a date of no more than two to five years after Jesus’ crucifixion. See, e.g., K. Lake, The Historical Evidence for the Resurrection of Jesus Christ (London: Williams and Norgate, 1907) 37–43; J. J. Smith, “Resurrection Faith Today,” TS 30 (1969) 403–4; G. -

Stars of 'The Following' Admit to Nightmares

LIFESTYLE37 WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 15, 2014 Chinese firm to build replica of Titanic Chinese firm plans to spend $165 moted or inherited in the east,” he said. million building a full-scale replica The replica will also recreate the Aof the Titanic-the doomed luxury experience of what it felt like when the liner which sank more than a century luxury liner collided with the iceberg, ago-as the main attraction for a theme Xinhua reported, though it gave no park, reports said yesterday. The original details of how the deadly collision would and supposedly unsinkable luxury pas- be replicated. Construction of the ship, senger liner struck an iceberg and went which is 270 meters (885 feet) long, is down in the North Atlantic in 1912, expected to be completed in two years killing more than 1,500 people. and will be based on designs of the The famous ship is a subject of Titanic’s sister ship, RMS Olympic, which immense fascination for many in China, was in service from 1911 to 1935, the particularly after the 1997 release of SCMP reported. “We already have com- James Cameron’s film on the liner’s plete design drawings, including a large doomed voyage starring Kate Winslet ballroom and premium first class rooms,” and Leonardo DiCaprio. Little known Su said in the Xinhua interview. Chinese energy company Seven Star Seven Star are not the only group Energy Investment said the replica, with dreams of recreating the Titanic. which is expected to cost 1 billion yuan Flamboyant Australian tycoon Clive ($165 million), will be the main attrac- Palmer previously unveiled a plan last tion for a planned theme park located year to build a sea-worthy replica of the (From left) Tiffany Boone, Jessica Stroup, Sam Underwood, Valorie Curry, Connie Nielson, James Purefoy, Kevin Bacon, and creator Kevin Sichuan, a landlocked province famous Titanic which is scheduled to make its Williamson are seen during the panel for “The Following” at the FOX Winter 2014 TCA at the Langham Hotel in Pasadena, Calif. -

Horror Movie Aesthetics

HORROR MOVIE AESTHETICS: How color, time, space and sound elicit fear in an audience. Thesis Presented by Xiangyi Fu to The Department of Art + Design In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts in Information Design and Visualization Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts May, 2016 2 ABSTRACT Fear is one of the most basic and important human emotions. At very beginning of movie history in 1895, when the audience first saw the Lumieres Bothers’ The Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat Station on the big screen, almost the entire audience tried to escape from the theater. The image of the approaching train caused fear. To intensify feelings of fear in the audience, film artists use sound, lighting, timing, motion and other stylistic devices. Among the wide range of film genres, especially horror movies aim to trigger a physiological and psychological response of fear in the audience. Within the genre, horror films differ widely from each other based on their time period, sub-genre, and regional differences including religious and cultural motifs. There many different ways of investigating how horror movies accomplish to terrify and horrify an audience, for example, via an analysis of plots, characters, and dialogue. This thesis examines what constitutes the different cinematic styles of horror movies – color/ lighting, time/motion, spatial relationships, and sound – in different horror movies. The result of my research is presented in an interactive visualization of cinematic aesthetics that enables a cinematic student to explore the patterns of how those elements are applied on the screen and can ultimately trigger and influence an audience’s mood. -

The Cost of Following Love and Sacrifice

The Cost of Following August 11, 2019 Part 8 of Unlocking the Way by Dr. Scott F. Heine Love and Sacrifice This past week, I enjoyed the honor of performing the wedding ceremony of a couple of wonderful friends that Margo and I met through my role directing a local community theater production last year. It was especially sweet because I had an opportunity to share briefly with those gathered, and I talked a bit about God’s vision for love as an act of self-sacrifice. I referred to God’s instructions to husbands and wives from Ephesians 5, where he tells husbands to love their wives as Christ loved the church and gave himself up for her, and where he tells wives to surrender themselves for the sake of honoring their husbands the way they surrender themselves for God’s glory. You see, God has woven the task of self-sacrifice into every home and every family, and when a couple can truly surrender themselves for someone else as an act of love, that’s the stuff that “happily ever after” is made of. This very idea of self-sacrifice is at the heart of our faith. It is the essence of Christianity. So it’s a shame that so many churches are tempted away from this Page 1 of 19 pinnacle of selflessness in favor of catering to the consumerism of our culture. Without realizing it, we reduce the gospel to a marketing appeal, proclaiming all that God does for us in loving us and redeeming us, while kind of hiding the cost of following Jesus somewhere in the fine print.