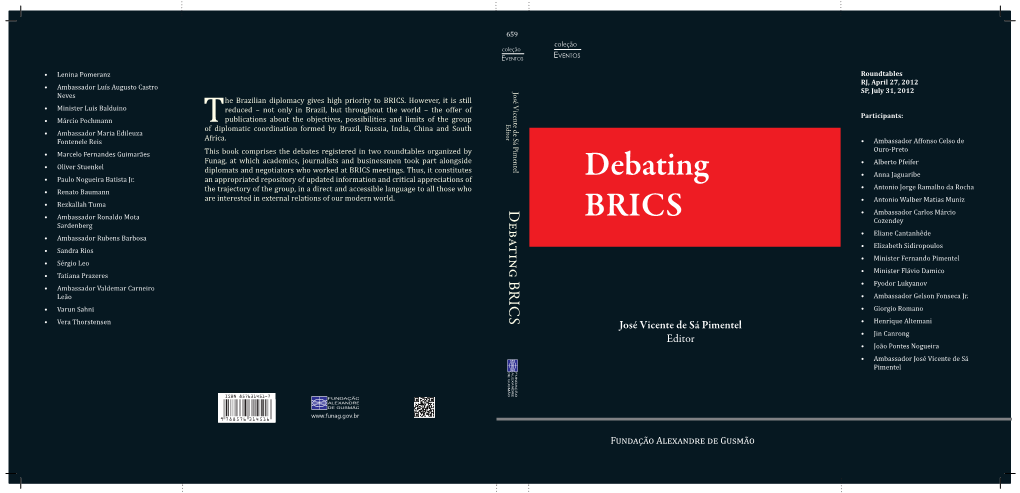

Debating BRICS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Week in Review on the ECONOMIC FRONT GDP: the Brazilian Statistics Agency (IBGE) Announced That GDP Growth for the Second Quarter Totaled 1.5%

POLICY MONITOR August 26 – 30 , 2013 The Week in Review ON THE ECONOMIC FRONT GDP: The Brazilian Statistics Agency (IBGE) announced that GDP growth for the second quarter totaled 1.5%. This year, GDP grew by 2.1%. Interest Rate: The Monetary Policy Committee (COPOM) of the Central Bank unanimously decided to raise interest rates by 0.5% to 9%--the fourth increase in a row. The Committee will hold two more meetings this year. Market analysts expect interest rates to rise by at least one more point to 10%. Strikes: Numerous groups of workers are under negotiations with the government for salary adjustments. Among those are regulatory agencies, national transportation department (DNIT), and livestock inspectors. DNIT workers have been on strike since June and livestock inspectors begun their strike on Thursday. On Friday, union workers will hold demonstrations throughout the country. Tourism: A study conducted by the Ministry of Tourism showed that the greatest cause of discontent for tourists coming to Brazil was high prices. The second most important reason was telecommunication services. Airport infrastructure, safety, and public transportation did not bother tourists as much and were ranked below both issues. Credit Protection: The Agency for Credit Protection Services (SPC Brasil) announced that the largest defaulting groups are in the middle class (Brazilian Class C). Forty-seven percent of all defaults are within Class C, 34% in Class B, and 13% in Class D. Forty-six percent of respondents claim to have been added to the list of default due to credit card payment delays and 40% due to bank loans. -

50Anos Depois Do Golpe

brasileiros no multilateralismo N A experiência brasileira à frente 7 de organizações internacionais 2014 os 50 anos dos 3ds Permanência e evolução de uma ideia tríade modernista no itamaraty Niemeyer, Burle Marx e Athos Bulcão DIPLOMACIA E HUMANIDADES JUCA política da indiscrição A vergonha pelo vazamento de informações Diplomacia e Transição Democrática 50 ANOS DEPOIS DO GOLPE CARTA dos EDITORES Os 50 anos do Golpe militar. As manifestações de junho de 2013. A crescente abertu- ra do Itamaraty ao diálogo com a sociedade civil. A exposição de limites da diploma- cia tradicional. A consolidação da liderança brasileira em importantes organizações multilaterais. Certamente, o período do curso de formação da Turma 2012-2014 do Instituto Rio Branco coincidiu com episódios marcantes para a diplomacia, a política e a sociedade brasileiras. A produção de mais um exemplar da JUCA não poderia passar ao largo desse tem- po de mudanças. O fato de sermos numericamente menos que os colegas das “Turmas de 100” não anulou o entusiasmo de propor inovações. Primeiramente, renovamos o projeto gráfico da Revista, de forma a reforçar a afinidade entre textos e identidade visual. Além disso, fomentamos parcerias com jovens acadêmicos, coautores de dois importantes artigos desta edição. “Last but not least”, a JUCA tem, pela primeira vez, seu conteúdo traduzido para o inglês. Com a edição bilíngue e a recém-lançada pági- na no Facebook (facebook.com/revistajuca), esperamos conquistar novas audiências, nos lugares mais distantes. Ao mesmo tempo em que instituímos mudanças, cuidamos da essência da JUCA. O conteúdo desta edição reitera o compromisso dos jovens diplomatas em tomar parte nas discussões relacionadas à profissão com a qual ainda se estão acostumando, além de revelar seus talentos e opiniões sobre arte, política, literatura e filosofia. -

Exemplar De Assinante Da Imprensa Nacional

ISSN 1677-7050 Ano LVI No- 120 Brasília - DF, sexta-feira, 26 de junho de 2015 COMITIVA OFICIAL: MINISTÉRIO DO TRABALHO E EMPREGO Sumário . - no período de 27 de junho a 2 de julho de 2015: Exposição de Motivos PÁGINA MAURO LUIZ IECKER VIEIRA, Ministro de Estado das Relações No 15, de 16 de junho de 2015. Afastamento do País do Ministro de Atos do Poder Executivo.................................................................... 1 Exteriores; Estado do Trabalho e Emprego, com ônus, no período de 26 de junho Presidência da República.................................................................... 1 ALOIZIO MERCADANTE OLIVA, Ministro de Estado Chefe da a 2 de julho de 2015, inclusive trânsito, com destino a Havana, Cuba, Casa Civil da Presidência da República; para participar de reuniões sobre a cooperação técnica entre o Mi- Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento ...................... 4 JOAQUIM VIEIRA FERREIRA LEVY, Ministro de Estado da Fazenda; nistério do Trabalho e Seguridade Social de Cuba e o Ministério do Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Inovação.................................. 6 Trabalho e Emprego do Brasil. Autorizo. Em 25 de junho de 2015. Ministério da Cultura.......................................................................... 6 RENATO JANINE RIBEIRO, Ministro de Estado da Educação; Ministério da Defesa........................................................................... 6 ARMANDO DE QUEIROZ MONTEIRO NETO, Ministro de Estado MINISTÉRIO DO MEIO AMBIENTE Ministério da Educação ................................................................... -

The Quest for Autonomythe Quest For

Política Externa coleção Brasileira THE QUEST FOR AUTONOMY MINISTRY OF EXTERNAL RELATIONS Foreign Minister Ambassador Luiz Alberto Figueiredo Machado Secretary-General Ambassador Eduardo dos Santos ALEXANDRE DE GUSMÃO FOUNDATION President Ambassador Sérgio Eduardo Moreira Lima Institute of Research on International Relations Director Ambassador José Humberto de Brito Cruz Center for Diplomatic History and Documents Director Ambassador Maurício E. Cortes Costa Editorial Board of the Alexandre de Gusmão Foundation President Ambassador Sérgio Eduardo Moreira Lima Members Ambassador Ronaldo Mota Sardenberg Ambassador Jorio Dauster Magalhães e Silva Ambassador Gonçalo de Barros Carvalho e Mello Mourão Ambassador Tovar da Silva Nunes Ambassador José Humberto de Brito Cruz Minister Luís Felipe Silvério Fortuna Professor Francisco Fernando Monteoliva Doratioto Professor José Flávio Sombra Saraiva Professor Antônio Carlos Moraes Lessa The Alexandre de Gusmão Foundation (Funag) was established in 1971. It is a public foundation linked to the Ministry of External Relations whose goal is to provide civil society with information concerning the international scenario and aspects of the Brazilian diplomatic agenda. The Foundation’s mission is to foster awareness of the domestic public opinion with regard to international relations issues and Brazilian foreign policy. Andrew James Hurrell THE QUEST FOR AUTONOMY THE EVOLUTION OF BRAZIL’S ROLE IN THE INTERNATIONAL SYSTEM, 1964 – 1985 Brasília – 2013 Copyright © Fundação Alexandre de Gusmão Ministério das Relações Exteriores Esplanada dos Ministérios, Bloco H Anexo II, Térreo, Sala 1 70170-900 Brasília-DF Telephones: +55 (61) 2030-6033/6034 Fax: +55 (61) 2030-9125 Website: www.funag.gov.br E-mail: [email protected] Editorial Staff: Eliane Miranda Paiva Fernanda Antunes Siqueira Gabriela Del Rio de Rezende Guilherme Lucas Rodrigues Monteiro Jessé Nóbrega Cardoso Vanusa dos Santos Silva Graphic Design: Daniela Barbosa Layout: Gráfica e Editora Ideal Impresso no Brasil 2014 H966 Hurrell, Andrew James. -

Antonio Jorge Ramalho Is Professor of International Relations at the University of Brasilia and Director of the Pandiá Calógeras Institute of the Ministry of Defense

48 Antonio Jorge Ramalho is Professor of International Relations at the University of Brasilia and Director of the Pandiá Calógeras Institute of the Ministry of Defense. The author alone is responsible for the opinions that follow, which shall not be associated to the official positions of the Brazilian Government. The author is grateful to CNPq & CAPES (through Pro-Defesa) for their support to the researches that made this article possible. A European–South American Dialogue A European–South International Security X Conference of Forte de Copacabana of Forte X Conference 49 Brazil Emerging in the Global Security Order Brazil in the Global Security Order: Principled Action and Immediate Responses to Long- Term Challenges Antonio Jorge Ramalho In these pages, I discuss Brazil’s foreign policy with the purpose of in- forming readers on traditional values and current attitudes that condi- tion the country’s decisions in the international realm. Before that, I sin- gle out some of the main trends in current international relations to con- textualize Brazil’s positions. I then portray Brazil’s perceptions of these trends and its reactions to the faltering leadership that threatens the ex- istent global order. I begin with a dilemma that involves sovereigns and their citizens, institutions and global governance. We are trapped in a dilemma. Current global norms and institutions do not provide the levels of governance necessary to effectively manage the prevalent interdependence of economies and societies. Initiated at the end of World War II, only recently has this process become acute. And, de- pending on how the international community manages it, it may bring promises of peace and prosperity for humanity: Unaddressed, it will en- danger the current world order, favoring realpolitik approaches to handle the installed multipolarity. -

Brazilian Foreign Policy Under Dilma Rousseff Diego Santos Vieira De

Journal of International Relations and Foreign Policy March 2014, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 19-42 ISSN: 2333-5866 (Print), 2333-5874 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). 2014. All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development The Benign Multipolarity: Brazilian Foreign Policy Under Dilma Rousseff Diego Santos Vieira de Jesus1 Abstract The aim is to explain Brazilian foreign policy in Dilma Rousseff’s administration, particularly the consolidation of the ‘South American anchor’, the attempts of rapprochement with the United States and the strengthening of cooperation with emerging economies in Asia and Africa. The first is related to more convergent preferences of Brazilian and other South American governments on the integration of productive chains, the consolidation of South American zone of peace and the implementation of social projects. The second are related to more convergent preferences of Brazilian and the U.S. governments on the coordination to fight the global economic crisis and reciprocal investments. The third is related to more convergent preferences of Brazilian government and emerging economies on the promotion of balanced North-South relations and South-South partnerships. Keywords: Brazil; foreign policy; Dilma Rousseff; South America; United States; BRICS Brazilian president Dilma Rousseff – whose administration started in January 2011 – developed a less personal foreign policy than the one developed by the previous administration of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (2003-2010). Rousseff seemed not to emphasize ideological identities and personal abilities. 1Diego Santos Vieira de Jesus holds a PhD in International Relations from Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (IRI/PUC-Rio), Brazil. He is a lecturer in International Relations at the International Relations Institute of the same university and at the School of Higher Education in Advertising and Marketing of Rio de Janeiro (ESPM-RJ), Brazil. -

Equipe Ministerial 2º Mandato Da Presidente Dilma

Ano XXIV - Nº 288 Janeiro de 2015 ENCARTE Departamento Intersindical de Assessoria Parlamentar Equipe Ministerial 2º Mandato da Presidente Dilma MINISTROS A PARTIR DE MINISTÉRIOS MINISTROS EM 2014 2015 Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Neri Geller - Secretário de Kátia Abreu (PMDB) Abastecimento (MAPA) Política Agrícola da Pasta senadora de Tocantins reeleita Gilberto Kassab (PSD) Ministério das Cidades (MCidades) Gilberto Magalhães Occhi ex-prefeito de São Paulo Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Aldo Rebelo (PCdoB) Clelio Campolina Diniz Inovação (MCTI) ex-ministro dos Esportes Ricardo Berzoini (PT) Ministério das Comunicações (MC) Paulo Bernardo Silva ex-deputado federal de São Paulo João Luiz Silva Ferreira (PT) Marta Suplicy (PT) Juca Ferreira, ex-secretário Ministério da Cultura (MinC) senadora de São Paulo municipal de cultura com mandato até 2019 de São Paulo Jaques Wagner (PT) Ministério da Defesa (MD) Celso Amorim ex-governador da Bahia Ministério do Desenvolvimento Agrário Laudemir André Müller Patrus Ananias de Sousa (PT) (MDA) Armando Monteiro (PTB) Ministério do Desenvolvimento, Indústria Mauro Borges Lemos senador de Pernambuco e Comércio Exterior (MDIC) com mandato até 2019 Ministério do Desenvolvimento Social e Tereza Campello (PT) Mantida Combate à Fome (MDS) Cid Gomes (Pros) Ministério da Educação (MEC) Henrique Paim (PT) ex-governador do Ceará Aldo Rebelo (PCdoB) George Hilton (PRB) Ministério do Esporte (ME) ex-deputado federal ex-deputado federal de de São Paulo Minas Gerais Joaquim Levy - ex-secretário do Ministério -

Brazil's Policy Toward Israel and Palestine in Dilma

Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional ISSN: 0034-7329 ISSN: 1983-3121 Instituto Brasileiro de Relações Internacionais Vigevani, Tullo; Calandrin, Karina Stange Brazil’s policy toward Israel and Palestine in Dilma Rousseff and Michel Temer’s administrations: have there been any shifts? Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional, vol. 62, no. 1, e009, 2019 Instituto Brasileiro de Relações Internacionais DOI: 10.1590/0034-7329201900109 Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=35860327009 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative Article Brazil’s policy toward Israel and Palestine in Dilma Rousseff and Michel Temer’s administrations: have there been any shifts? DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0034-7329201900109 Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional Rev. Bras. Polít. Int., 62(1): e009, 2019 ISSN 1983-3121 http://www.scielo.br/rbpi Abstract Tullo Vigevani1 This paper analyzes Brazil’s relationship with Israel and Palestine during the 1Universidade Estadual Paulista, Rousseff (2011–2016) and Temer (2016–2018) administrations. We consider Programa de Pós-Graduação em Relações Internacionais, São Paulo, SP, Brazil the political and economic crises in Brazil since 2014, and their consequences ([email protected]) in foreign policy. Our question is whether there was room for changes, and ORCID ID: we attempt to understand if there were conditions for a shift in Brazilian orcid.org/0000-0001-6698-8291 foreign policy for the Middle East. -

5º Encontro Nacional Da ABRI Redefinindo a Diplomacia Em Um Mundo Em Transformação

5º Encontro Nacional da ABRI Redefinindo a Diplomacia em um Mundo em Transformação 29 a 31 de Julho de 2015 Belo Horizonte – MG – Brasil Análise de Política Externa DILMA ROUSSEFF’S PRESIDENCY AND ARAB COUNTRIES: AN OVERLOOKED FOREIGN POLICY? Danillo Alarcon Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Goiás Dilma Rousseff’s Presidency and Arab Countries: an overlooked foreign policy? ABSTRACT: Despite her poor results in terms of foreign policy, Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff has been applying the constitutional principles of the country’s international relations. Nonetheless, in a country such as Brazil, where the president usually has a great amount of power, particularly because of the “presidential diplomacy” of both Fernando Henrique Cardoso and Lula da Silva, Rousseff has had problems to operationalize her foreign policy objectives, if there are any critics could argue on. One exemplificative case happened in the second half of 2014, when she openly criticized the United States and its allies attacks against the Islamic State. Brazilian media was not sympathetic to her. It is clear, from a Foreign Policy Analysis standpoint, that her speech was not aimed at denying the horrific acts of the so-called terrorist organization, but at trying to bring back respect for international law and the United Nations role in those situations. However, according to Christopher Hill, the decision-making process in a democracy has to bear in mind a great amount of constituencies, from the media, that has a huge influence on public opinion, to the finance donors of elections and all other kinds of activities. In this sense, the objective of this paper is to analyze Rousseff’s administration relations with Arab Countries, specially focusing on the country’s view on the Arab Spring movements and its subsequent consequences. -

Defesa De Dilma Deve Contestar Até Amanhã Libelo Da Acusação

www.senado.leg.br/jornal Ano XXII — Nº 4.559 — Brasília, quinta-feira, 11 de agosto de 2016 Defesa de Dilma deve contestar até amanhã libelo da acusação Senado recebeu ontem o documento que resume as denúncias contra a presidente afastada e pede que ela perca definitivamente o mandato documento com a exposição do fato Oconsiderado crimi- noso e o reforço do pedido de punição da presidente Marcos Oliveira/Agência Senado afastada Dilma Rousseff, chamado libelo acusató- rio, foi entregue ontem ao Senado pelos advogados responsáveis pela denúncia que motivou o processo de impeachment. A peça pro- cessual, com nove páginas, pede que Dilma seja con- denada à perda definitiva do mandato e à inabilitação para exercer cargos públi- cos por oito anos. Dilma já foi intimada por meio de seu advogado, José Eduardo Cardozo. A defesa tem até amanhã à tarde para apre- O advogado João Berchmans (D) entrega a Celso Dias dos Santos, da Secretaria-Geral da Mesa, a peça acusatória final contra Dilma Rousseff, com nove páginas sentar o contraditório. 3 Avança texto que Indicados para ONU e embaixada recria Ministério em Portugal passam em sabatina da Cultura 3 As indicações dos diplo- ontem pela Comissão de Rela- França/Agência Senado Pedro matas Mauro Vieira, para ções Exteriores e agora vão a MP sobre nova chefiar a representação do Plenário. Indicados por Michel estrutura ministerial Brasil na ONU, e Luiz Alberto Temer, os dois já foram minis- Figueiredo, para a embaixada tros das Relações Exteriores de vai para a Câmara 3 em Portugal, foram aprovadas Dilma Rousseff. -

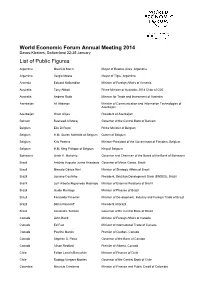

List of Public Figures

World Economic Forum Annual Meeting 2014 Davos-Klosters, Switzerland 22-25 January List of Public Figures Argentina Mauricio Macri Mayor of Buenos Aires, Argentina Argentina Sergio Massa Mayor of Tigre, Argentina Armenia Edward Nalbandian Minister of Foreign Affairs of Armenia Australia Tony Abbott Prime Minister of Australia; 2014 Chair of G20 Australia Andrew Robb Minister for Trade and Investment of Australia Azerbaijan Ali Abbasov Minister of Communication and Information Technologies of Azerbaijan Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev President of Azerbaijan Bahrain Rasheed Al Maraj Governor of the Central Bank of Bahrain Belgium Elio Di Rupo Prime Minister of Belgium Belgium H.M. Queen Mathilde of Belgium Queen of Belgium Belgium Kris Peeters Minister-President of the Government of Flanders, Belgium Belgium H.M. King Philippe of Belgium King of Belgium Botswana Linah K. Mohohlo Governor and Chairman of the Board of the Bank of Botswana Brazil Antônio Augusto Junho Anastasia Governor of Minas Gerais, Brazil Brazil Marcelo Côrtes Neri Minister of Strategic Affairs of Brazil Brazil Luciano Coutinho President, Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES), Brazil Brazil Luiz Alberto Figueiredo Machado Minister of External Relations of Brazil Brazil Guido Mantega Minister of Finance of Brazil Brazil Fernando Pimentel Minister of Development, Industry and Foreign Trade of Brazil Brazil Dilma Rousseff President of Brazil Brazil Alexandre Tombini Governor of the Central Bank of Brazil Canada John Baird Minister of Foreign Affairs of Canada Canada Ed Fast Minister -

Iii Conferência Global Sobre Trabalho Infantil Relatório Final

III CONFERÊNCIA GLOBAL SOBRE TRABALHO INFANTIL RELATÓRIO FINAL Ministério do Desenvolvimento Social e Combate à Fome - MDS De 8 a 10 de outubro de 2013 Brasília, Brasil Copyright © Ministério do Desenvolvimento Social e Combate à Fome. 2014 Brasil. Ministério do Desenvolvimento Social e Combate à Fome (MDS). Organização Internacional do Trabalho (OIT). III Conferência Global sobre Trabalho Infantil: relatório final. -- Brasília, DF: Secretaria de Avaliação e Gestão da Informação, 2014. 132 p. ; 22 cm. ISBN: 978-85-60700-71-4 1. Trabalho infantil. 2. Conferencia global, relatório. I. Organização Interna- cional do Trabalho. CDU 331-053.2 FICHA TÉCNICA Ministério do Desenvolvimento Social e Combate à Fome (MDS) Ministra Tereza Campello Secretário Executivo Marcelo Cardona Rocha Secretária de Assistência Social Denise Ratmann Arruda Colin Secretária Executiva da III Conferência Global sobre Trabalho Infantil Paula Montagner Assessora Internacional Claudia de Borba Maciel Equipe envolvida Adriana Braz Adriana Miranda Moraes Adrianna Figueiredo Alex Kleyton Rodrigues Barbosa Amanda Guedes Ana Cláudia Nascimento Ana Paula Siqueira André Luís Quaresma de Carvalho André Luiz Silva Gomes Anelise Borges Souza Anna Rita Scott Kilson Bárbara Pincowsca Cardoso Campos Benício Marques Carolina Terra Daniel Plech Garcia (Secretaria Executiva da III CGTI) David Urcino Ferreira Braga Eduardo de Medeiros Santana Fábio Macario Fernanda Sarkis Franchi Nogueira Fernando Kleiman Francisco Antonio de Sousa Brito Ganesh Inocalla Guilherme Pereira Larangeira Iara Cristina da Silva Alves Ivone Alves de Oliveira João Augusto Sobreiro Sigora Joaquim Travassos Katia Rovana Ozorio Laura Aparecida Pequeno da Rocha Ligia Girão (Secretaria Executiva da III CGTI) Ligia Margaret Kosin Jorge Luciana de Fátima Vidal Marcelo Saboia Marcia Muchagata (Secretaria Executivaa da III CGTI) Mônica Aparecida Rodrigues Nadia Marcia Correia Campos Natascha Rodenbusch Valente Olímpio Antônio Brasil Cruz Pollyanna Rodrigues Costa Priscilla Craveiro da C.