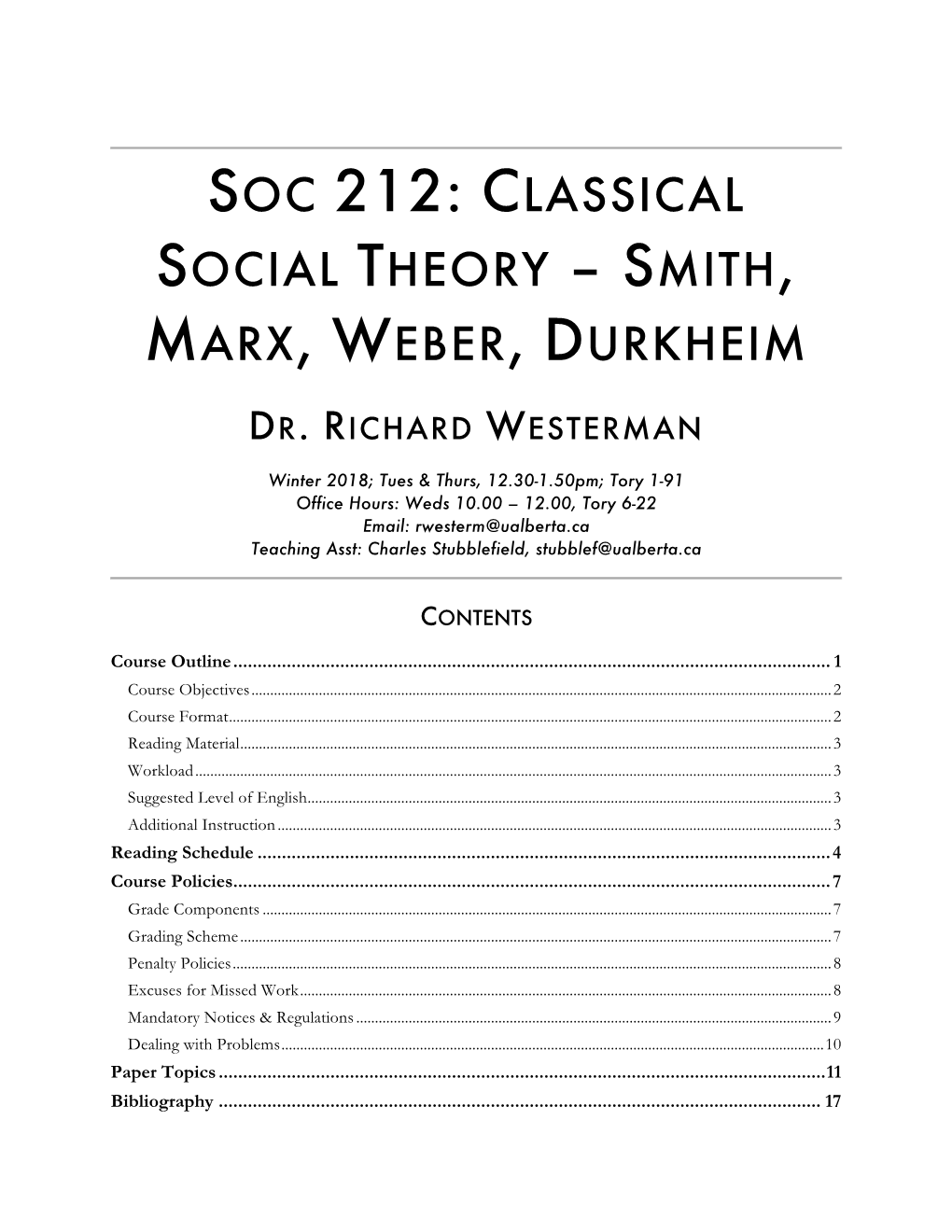

Soc 212: Classical Social Theory – Smith, Marx, Weber, Durkheim

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A New Look at Max Weber and His Anglo-German Family Connections1

P1: JLS International Journal of Politics, Culture and Society [ijps] PH231-474840-07 October 28, 2003 17:46 Style file version Nov. 19th, 1999 International Journal of Politics, Culture and Society, Vol. 17, No. 2, Winter 2003 (C 2003) II. Review Essay How Well Do We Know Max Weber After All? A New Look at Max Weber and His Anglo-German Family Connections1 Lutz Kaelber2 Guenther Roth’s study places Max Weber in an intricate network of ties among members of his lineage. This paper presents core findings of Roth’s analysis of Weber’s family relations, discusses the validity of Roth’s core theses and some of the implications of his analysis for Weber as a person and scholar, and addresses how Roth’s book may influence future approaches to Weber’s sociology. KEY WORDS: Max Weber; history of sociology; classical sociology; German history; Guenther Roth. “How well do we know Max Weber?”—When the late Friedrich H. Tenbruck (1975) raised this question almost thirty years ago, he had Weber’s scholarship in mind. The analysis of Weber’s oeuvre and the debate over it, fueled by a steady trickle of contributions of the Max Weber Gesamtaus- gabe, has not abated since. Thanks to the Gesamtausgabe’s superbly edited volumes, we now know more about Weber the scholar than ever before, even though the edition’s combination of exorbitant pricing and limitation to German-language editions has slowed its international reception. Tenbruck’s question might be applied to Weber’s biography as well. Here, too, the Gesamtausgabe, particularly with the edition of his personal letters, has been a valuable tool for research.1 Yet the fact remains that what we know about Weber the person derives to a significant extent from 1Review essay of Guenther Roth, Max Webers deutsch-englische Familiengeschichte, 1800–1950. -

Grading: All Readings Will Be Posted on the Yale Canvas Course Website

Sociology 151 FOUNDATIONS OF MODERN SOCIAL THEORY Summer 2020 Session A: May 25th-June 26th Professor Julia Adams [email protected] Summer Office Hours: flexible: after class or by appointment ***Class meets M,W,F, 9-11:15 am, on Zoom*** Hobbes; Locke; Montesquieu; Rousseau; Martineau; Mill; Hegel; Marx; Weber; Durkheim. In this concentrated survey course, students explore the writings of classical Western theorists of social and political life in modernity, as they tackle key problems and challenges that continue to preoccupy us today. Modern social life and social science arose in tandem, and this class focuses on the ways that the classical theorists made sense of the beginning of capitalism; individualism and alienation; the family; religion; power struggles and the rise of states. Most important, in this class you will begin to develop your own thoughts and arguments, built on the foundation of modern social theory. The course format combines orienting lectures and seminar-style class discussions and debates. There are two take-home exams, the first due on or before June 12, and the second on or before the last day of class. Students will also write an essay, due on or before the last day of class. Detailed exam review sheets and potential essay topics will be distributed in advance. Grading: Attendance and participation, 10% … Exams, 50% … Essay, 40% … …of the final grade. All readings will be posted on the Yale Canvas course website SCHEDULE May 25, Monday: Welcome; Social Theory; General Organization of Course May 27, Wednesday: The Problem of Social Order: Hobbes Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan Selections (emphasis on chapters 6-8, 11-14, 17, 30) May 29, Friday: Equality, Freedom, Property, and Dissent: Locke John Locke, Second Treatise of Government Selections (posted) June 1, Monday: The Division of Political Powers: Montesquieu Montesquieu, The Spirit of the Laws Part I, Book 1-3, pp. -

Sandage, Ph.D

79‐245, Fall 2019 Dr. Scott A. Sandage, Ph.D. Classroom: Baker 237B Associate Professor of History Office: Baker Hall 236B [email protected] Office Hours: Tues 8am‐9am & by appt. Office phone: 412/268‐2878 Capitalism and Individualism in American Culture Are you what you do? Will your career choice and achievements define who you are, how you feel about yourself, and how others see you as a person? This course explores the cultural history of American capitalism through three ongoing themes: 1) the relation between work and identity; and 2) the concept of individualism; and 3) the historical origins of your opinions on 1&2. Learning and skills objectives include: To be able to explain how work (and attitudes toward it) have changed from the eighteenth to the twenty‐first century; To be able to read critically, relating different genres of writing, from different historical periods, to the main themes of the course; and To be able to write analytically, integrating multiple sources including your own judgments, in both formal (essays) and informal (journal) styles. There are no exams (except short, unannounced readings quizzes, if necessary). Instead, students will keep a journal (collected at regular intervals) and write four essays, three short (750‐1250 words) and one longer (1250‐1500 words). Grading criteria: Grading weights are as follows: journal = 25%; first short essay = 10%; second short essay = 15%; third short essay = 15%; final essay = 25%; attendance and participation = 10%. Required Readings: Benjamin Franklin, Autobiography (Dover edition) Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life (Dover) Ralph Waldo Emerson, Self‐Reliance and Other Essays (Dover) Henry David Thoreau, Walden (Dover) Henry David Thoreau, Civil Disobedience and Other Essays (Dover) Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Women and Economics (Dover) Arthur Miller, The Death of a Salesman (Penguin) Malcolm Gladwell, Outliers: The Story of Success (Back Bay) Additional required readings are available (PDF) at https://canvas.cmu.edu/. -

Dilemmas in Liberal Democratic Thought Since Max Weber

Richard Wellen Dilemmas In Liberal Democratic Thought Since Max Weber Wellen, Richard Dilemmas in Liberal Democratic Thought Since Max Weber ISBN: 978-0-9738413-0-5 First edition published in 1996 by Peter Lang Publishing, Inc., New York. © by Richard Wellen This work is licensed by Richard Wellen under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc- nd/3.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. Anyone is free to copy, distribute and transmit this work on condition that the work is attributed to the author, that it is not used or distributed for commercial purposes and that it is not altered, transformed or used as a source for derivative works. Author’s contact information: [email protected] For Sally, Sarah and Ruthie Contents Acknowledgements ix 1. Weber’s Challenge to Political Thought 1 2. The Necessity of Choice: Toward a 31 Convergence of Personality and Politics 3. Liberalism as a Moral Tradition: 57 Vice as Virtue? 4. The Modernization of Political Reason: 83 Reflections on Habermas 5. The Crisis of Liberalism in Social Science: 111 Strauss on Weber 6. Rorty’s End of Philosophy: 135 A New Beginning for Liberalism? 7. On the Moral Contingency of 159 Liberal Democratic Politics Bibliography Index Acknowledgements The idea of addressing the relevance of Max Weber's work to contemporary political thought was suggested to me by John O'Neill during the formative stages of this project. -

Montesquieu on Commerce, Conquest, War, and Peace

MONTESQUIEU ON COMMERCE, CONQUEST, WAR, AND PEACE Robert Howse* I. INTRODUCTION:COMMERCE AS THE AGENT OF PEACE:MONTESQUIEU AND THE IDEOLOGY OF LIBERALISM n the history of liberalism, Montesquieu, who died two hundred and Ififty years ago, is an iconic figure. Montesquieu is cited as the source of the idea of checks and balances, or separation of powers, and thus as an intellectual inspiration of the American founding.1 Among liberal internationalists, Montesquieu is known above all for the notion that international trade leads to peace among nation-states. When liberal international relations theorists such as Michael Doyle attribute this posi- tion to Montesquieu,2 they cite Book XX of the Spirit of the Laws,3 in which Montesquieu claims: “The natural effect of commerce is to bring peace. Two nations that negotiate between themselves become recipro- cally dependent, if one has an interest in buying and the other in selling. And all unions are based on mutual needs.”4 On its own, Montesquieu’s claim raises many issues. Montesquieu’s point is that trade based on mutual dependency discourages war. Here, Montesquieu abstracts entirely from the relative power of the states in question, a concern that is pervasive in his concrete analyses of relation- ships among political communities. For example, later on in the same section of the Spirit of the Laws he mentions that trade relations between Carthage and Marseille led to jealousy and a security conflict: There were, in the early times, great wars between Carthage and Mar- seille concerning the fishery. After the peace, they competed in eco- nomic commerce. -

Information Libertarianism

Information Libertarianism Jane R. Bambauer & Derek E. Bambauer* Legal scholarship has attacked recent First Amendment jurisprudence as unprincipled: a deregulatory judicial agenda disguised as free speech protection. This scholarly trend is mistaken. Descriptively, free speech protections scrutinize only information regulation, usefully pushing government to employ more direct regulations with fewer collateral consequences. Even an expansive First Amendment is compatible with the regulatory state, rather than being inherently libertarian. Normatively, courts should be skeptical when the state tries to design socially beneficial censorship. This Article advances a structural theory that complements classic First Amendment rationales, arguing that information libertarianism has virtues that transcend political ideology. Regulating information is peculiarly difficult to do well. Cognitive biases cause regulators to systematically overstate risks of speech and to discount its benefits. Speech is strong in its capacity to change behavior, yet politically weak. It is a popular scapegoat for larger societal problems and its regulation is an attractive option for interest groups seeking an advantage. Collective action, public choice, and government entrenchment problems arise frequently. First Amendment safeguards provide a vital counterpressure. Information libertarianism encourages government to regulate conduct directly because when the state censors communication, the results are often DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15779/Z38Z31NN40 Copyright -

The Influence of the German Idealist Tradition Upon Weberian Thought

13 THE INFLUENCE OF THE GERMAN IDEALIST TRADITION UPON WEBERIAN THOUGHT by Nancy Herman ABSTRACT Max Weber was one of the prominant social figures in this history of the social sciences for he made significant contributions to the development of anthropology, sociology and social theory as a whole. Weber's aim was explicit: he wanted to develop a 'scientific study of man and society:' he sought not only to delineate the scope of the discipline but also wanted to construct a clear-cut methodology whereby data could be rigorously studied in accordance with the testable procedures of science. This paper discusses the influence of the German idealist tradition upon Max Weber. Specifically, this study critically examines Weberion thought in terms of illustrating how he combined the Germanic emphasis on the search for subjective meanings with the positivist notion of scientific rigor, and in so doing was able to bridge the. dichotomy between the idealist and positivist traditions. RESUME Max Weber fut l'une des personalites illustres de l'historie des sciences sociales car il apporta une contribution importante au developpement de l'anthropologie, de la sociologie, et de la theorie social dans son ensemble. Le but de Weber etait clair: il vou1 ait organi ser une etude scientifique de l'homme et de la societe: i1 cherchait non seu1ement a delimiter le domaine de la discipline, mais aussi a delimiter une methodol ogi e preci se qui permettrait une etude rigoureuse des donnees en accord avec les procedes fiables de la science. Cet article measure l'inf1uence de la tradition idealiste allemande sur Max Weber. -

Re-Reading Weber, Or: the Three Fields for the Analysis of Power in International Relations

DIIS · DANISH INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDIES STRANDGADE 56 · 1401 COPENHAGEN K · DENMARK TEL +45 32 69 87 87 · [email protected] · www.diis.dk RE-READING WEBER, OR: THE THREE FIELDS FOR THE ANALYSIS OF POWER IN INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS Stefano Guzzini DIIS Working Paper no 2007/29 © Copenhagen 2007 Danish Institute for International Studies, DIIS Strandgade 56, DK-1401 Copenhagen, Denmark Ph: +45 32 69 87 87 Fax: +45 32 69 87 00 E-mails: [email protected] Web: www.diis.dk Cover Design: Carsten Schiøler Printed in Denmark by Vesterkopi as ISBN: 978-87-7605-242-3 Price: DKK 25.00 (VAT included) DIIS publications can be downloaded free of charge from www.diis.dk DIIS Working Papers make available DIIS researchers’ and DIIS project partners’ work in progress towards proper publishing. They may include important documentation which is not necessarily published elsewhere. DIIS Working Papers are published under the responsibility of the author alone. DIIS Working Papers should not be quoted without the express permission of the author. Stefano Guzzini, Senior Researcher, DIIS and Professor of Government, Uppsala University Contents Abstract..............................................................................................................................................2 Acknowledgements........................................................................................................................2 Introduction......................................................................................................................................3 -

The Perspective of Sociology

Environmentalist DOI 10.1007/s10669-011-9357-2 A transatlantic approach to sustainability? The perspective of sociology Stephen Kalberg Ó Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2011 Abstract Differing views of the state and varying ideo- Reference to at least several of the discipline’s major logical postures in the United States and Europe place explanatory variables—such as class, status groups, ethnic ‘‘invisible and clandestine’’ obstacles against the smooth groups, organizations, the state, power, gender, ideology, functioning of transatlantic treaties, agreements, and coop- and religion—must occur. According to sociologists, eration in general. These differing views and postures must because all of these variables influence the formation of be rendered visible and acknowledged if efforts to perpet- environmental policy, they must ultimately be incorporated uate a cross-Atlantic dialog are to be viable and stable. on a regular basis into sustainability-oriented investigations. Neither the advantages of sharing technology nor common This study cannot address the influence of all groups economic and political interests will alone adequately pivotal to sociologists. It attends exclusively to two con- ground cooperation. Sociologists in particular are aware of cepts indispensable for the study of transatlantic relations the ways in which indigenous values and beliefs frequently and powerful as causal factors. First, the foundational role endure, despite the homogenizing structural change that of the state will be briefly examined. This article then turns accompanies industrialization, urbanization, and globaliza- to its major theme: the importance of ideology. Often tion, and cause misperceptions and misunderstandings. amorphous and difficult to identify, ideologies may obstruct—frequently clandestinely—all attempts to for- Keywords Transatlantic dialog Á Ideology Á Small state Á mulate coherent transatlantic policies. -

7. Hayek and Mises Richard M

7. Hayek and Mises Richard M. Ebeling There is no single man to whom I owe more intellectually, even though he [Ludwig von Mises] was never my teacher in the institutional sense of the word . Although I do owe him a decisive stimulus at a crucial point in my intellec- tual development, and continuous inspiration through a decade, I have perhaps most profited from his teaching because I was not initially his student at the university, an innocent young man who took his word for gospel, but came to him as a trained economist . Though I learned that he was usually right in his conclusions, I was not always satisfied with his arguments, and retained to the end a certain critical attitude which sometimes forced me to build different constructions, which however, to my great pleasure, usually led to the same conclusions. (F.A. Hayek, ‘Coping with ignorance’, 1978, pp. 17–18) LUDWIG VON MISES AND FRIEDRICH A. HAYEK IN VIENNA In the twentieth century, the two economists most closely identified as representing the Austrian School of economics were Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich A. Hayek. Indeed, more than any other members of the Austrian School, Mises and Hayek epitomize the academic and public perception of the ‘Austrian’ approach to economic theory and method, as well as a free-market- oriented view of social and economic policy. Their names have been inseparable from the conception of the ‘Austrian’ theory of the business cycle; or the ‘Austrian’ critique of socialist central planning and government intervention; or the ‘Austrian’ view of competition and the market process; or the ‘Austrian’ emphasis on the unique characteris- tics that separate the social sciences from the natural sciences.1 Yet, as Hayek emphasizes in the quotation with which the chapter begins, he never directly studied with Mises as a student at the University of Vienna; and while considering him the thinker who had the most influ- ence on him in his own intellectually formative years of the 1920s and early 1930s, he approached Mises’ ideas with a critical eye. -

How Capitalism Lost Its Soul Marie-Laure Salles-Djelic

How Capitalism Lost its Soul Marie-Laure Salles-Djelic To cite this version: Marie-Laure Salles-Djelic. How Capitalism Lost its Soul: From Protestant Ethics to Robber Barons. D. Daianu; Radu Vranceanu. Ethical Boundaries of Capitalism, Ashgate Publishing, pp.43 - 64, 2005, 9780754643951. hal-01892001 HAL Id: hal-01892001 https://hal-sciencespo.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01892001 Submitted on 10 Oct 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. How Capitalism Lost its Soul From Protestant Ethics to Robber Barons Marie-Laure Djelic, ESSEC, France Published in Daianu, D. and Vranceanu, R. (eds), Ethical Boundaries of Capitalism, Ashgate 2005 1. Introduction A serious discussion of capitalism and its development cannot avoid the confrontation, at one moment or another, with ethical issues. Historically, there have been quite a number of different positions in the debate – giving us a sense that the confrontation is, indeed, a complex one. When it comes to the connection between ethics and capitalism, we can differentiate between at least four different ideal typical perspectives. First, we find what we call the missionary perspective. „Missionaries‟ are in general associated with the liberal tradition. -

A Perspective from Weberian Economic Sociology

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Boeddeling, Jann Working Paper Corporate social responsibility: A perspective from Weberian economic sociology Discussion Papers, No. 22/2012 Provided in Cooperation with: Witten/Herdecke University, Faculty of Management and Economics Suggested Citation: Boeddeling, Jann (2012) : Corporate social responsibility: A perspective from Weberian economic sociology, Discussion Papers, No. 22/2012, Universität Witten/ Herdecke, Fakultät für Wirtschaftswissenschaft, Witten This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/56042 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der