Buddhist Logic in India and China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddha Speaks Mahayana Sublime Treasure King Sutra (Also Known As:) Avalokitesvara-Guna-Karanda-Vyuha Sutra Karanda-Vyuha Sutra

Buddha speaks Mahayana Sublime Treasure King Sutra (Also known as:) Avalokitesvara-guna-karanda-vyuha Sutra Karanda-vyuha Sutra (Tripitaka No. 1050) Translated during the Song Dynasty by Kustana Tripitaka Master TinSeekJoy Chapter 1 Thus I have heard: At one time, the Bhagavan was in the Garden of the Benefactor of Orphans and the Solitary, in Jeta Grove, (Jetavana Anathapindada-arama) in Sravasti state, accompanied by 250 great Bhiksu(monk)s, and 80 koti Bodhisattva-Mahasattvas, whose names are: Vajra-pani(Diamond-Hand) Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Wisdom-Insight Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Vajra-sena(Diamond-Army) Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Secret- Store Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Akasa-garbha(Space-Store) Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Sun- Store Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Immovable Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Ratna- pani(Treasure-Hand) Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Samanta-bhadra(Universal-Goodness) Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Achievement of Reality and Eternity Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Eliminate-Obstructions(Sarva-nivaraNaviskambhin) Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Great Diligence and Bravery Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Bhaisajya-raja(Medicine-King) Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Avalokitesvara(Contemplator of the Worlds' Sounds) Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Vajra-dhara(Vajra-Holding) Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Ocean- Wisdom Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Dharma-Upholding Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, and so on. At that time, there were also many gods of the 32 heavens, leaded by Mahesvara(Great unrestricted God) and Narayana, came to join the congregation. They are: Sakra Devanam Indra the god of heavens, Great -

Lankavatara-Sutra.Pdf

Table of Contents Other works by Red Pine Title Page Preface CHAPTER ONE: - KING RAVANA’S REQUEST CHAPTER TWO: - MAHAMATI’S QUESTIONS I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX X XI XII XIII XIV XV XVI XVII XVIII XIX XX XXI XXII XXIII XXIV XXV XXVI XXVII XXVIII XXIX XXX XXXI XXXII XXXIII XXXIV XXXV XXXVI XXXVII XXXVIII XXXIX XL XLI XLII XLIII XLIV XLV XLVI XLVII XLVIII XLIX L LI LII LIII LIV LV LVI CHAPTER THREE: - MORE QUESTIONS LVII LVII LIX LX LXI LXII LXII LXIV LXV LXVI LXVII LXVIII LXIX LXX LXXI LXXII LXXIII LXXIVIV LXXV LXXVI LXXVII LXXVIII LXXIX CHAPTER FOUR: - FINAL QUESTIONS LXXX LXXXI LXXXII LXXXIII LXXXIV LXXXV LXXXVI LXXXVII LXXXVIII LXXXIX XC LANKAVATARA MANTRA GLOSSARY BIBLIOGRAPHY Copyright Page Other works by Red Pine The Diamond Sutra The Heart Sutra The Platform Sutra In Such Hard Times: The Poetry of Wei Ying-wu Lao-tzu’s Taoteching The Collected Songs of Cold Mountain The Zen Works of Stonehouse: Poems and Talks of a 14th-Century Hermit The Zen Teaching of Bodhidharma P’u Ming’s Oxherding Pictures & Verses TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE Zen traces its genesis to one day around 400 B.C. when the Buddha held up a flower and a monk named Kashyapa smiled. From that day on, this simplest yet most profound of teachings was handed down from one generation to the next. At least this is the story that was first recorded a thousand years later, but in China, not in India. Apparently Zen was too simple to be noticed in the land of its origin, where it remained an invisible teaching. -

Hold on to the Fundamental Principle of Oneness Sri Sathya Sai Baba

Divine Discourse, 6 September 1996 Hold on to the Fundamental Principle of Oneness Sri Sathya Sai Baba Prasanthi Nilayam 6 September 1996 Editor’s note. This discourse appears in the Sathya Sai Speaks series but was retranslated and appeared in Sanathana Sarathi in two parts in April and May 2015. Pots are many, clay is one, Jewels are many, gold is one, If there is no potter, clay cannot be converted into Cows are many, milk is one, pots. And the potter cannot make pots without Likewise, the same Divinity dwells in all forms. clay. Therefore, both —potter and clay— are nec- (Sanskrit verse) essary for pots to be made. If you enquire deeply, you will find in this world For the entire universe, God is the primary cause, that the same thing assumes different names and and He is also the creative force of the universe. forms and is put to use in myriad ways. Seed is Your bodies are like different pots. You put your one, from which emerge the trunk, branches, sub- body to different uses and experience pleasure and branches, leaves, flowers, and fruits of the tree. pain. Just as the pot breaks when it falls down, the All these have different names and forms and are body also perishes when the time comes. put to use in different ways. The One willed to become many (Ekoham bahusyam). Though God But God, who is both the instrumental cause and is one, He assumes many names and forms. the primary cause, is permanent. The same pot, which is useful, becomes useless when it breaks. -

Publications Received by the Regional Editor for South-Asia (From January 2010 to December 2011)

Publications received by the regional editor for South-Asia (from January 2010 to December 2011) Autor(en): Bronkhorst, Johannes Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Asiatische Studien : Zeitschrift der Schweizerischen Asiengesellschaft = Études asiatiques : revue de la Société Suisse-Asie Band (Jahr): 66 (2012) Heft 2 PDF erstellt am: 08.10.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-306447 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch PUBLICATIONS RECEIVED BY THE REGIONAL EDITOR FOR SOUTH-ASIA FROM JANUARY 2010 TO DECEMBER 2011) Achard, Jean-Luc ed.) 2010): Etudes tibétaines en l’honneur d’Anne Chayet. Genève: Droz. Ecole Pratiques des Hautes Etudes, sciences historiques et philologiques – II; Hautes études orientales – Extreme-Orient 12/49.) Acta Comparanda 21 Faculty for Comparative Study of Religions, Antwerpen, Belgium). -

Indian Philosophy Encyclopædia Britannica Article

Indian philosophy Encyclopædia Britannica Article Indian philosophy the systems of thought and reflection that were developed by the civilizations of the Indian subcontinent. They include both orthodox (astika) systems, namely, the Nyaya, Vaisesika, Samkhya, Yoga, Purva-mimamsa, and Vedanta schools of philosophy, and unorthodox (nastika) systems, such as Buddhism and Jainism. Indian thought has been concerned with various philosophical problems, significant among them the nature of the world (cosmology), the nature of reality (metaphysics), logic, the nature of knowledge (epistemology), ethics, and religion. General considerations Significance of Indian philosophies in the history of philosophy In relation to Western philosophical thought, Indian philosophy offers both surprising points of affinity and illuminating differences. The differences highlight certain fundamentally new questions that the Indian philosophers asked. The similarities reveal that, even when philosophers in India and the West were grappling with the same problems and sometimes even suggesting similar theories, Indian thinkers were advancing novel formulations and argumentations. Problems that the Indian philosophers raised for consideration, but that their Western counterparts never did, include such matters as the origin (utpatti) and apprehension (jñapti) of truth (pramanya). Problems that the Indian philosophers for the most part ignored but that helped shape Western philosophy include the question of whether knowledge arises from experience or from reason and distinctions such as that between analytic and synthetic judgments or between contingent and necessary truths. Indian thought, therefore, provides the historian of Western philosophy with a point of view that may supplement that gained from Western thought. A study of Indian thought, then, reveals certain inadequacies of Western philosophical thought and makes clear that some concepts and distinctions may not be as inevitable as they may otherwise seem. -

Upanishads Divine Discourses of Bhagawan Sri Sathya Sai Baba

Summer Showers 1991 - Upanishads Divine Discourses of Bhagawan Sri Sathya Sai Baba Index Of Discourses 1. The End Of Education Is Character ...................................................................... 2 2. The Vedic Heritage Of India ................................................................................. 15 3. Thath Twam Asi —that Thou Art......................................................................... 31 4. Isaavaasya Upanishad – Renunciation And Pleasure ........................................ 42 5. Kenopanishad ......................................................................................................... 55 6. Prasnopanishad – Answers To The First Student .............................................. 65 7. Prasnopanishad – Answers To The Second And Third Students ..................... 80 8. Prasnopanishad – Answers To The Fourth And Fifth Students ....................... 90 9. Prasnopanishad – Answers To The Sixth Student ............................................ 101 10. Mundaka Upanishad And Brahma Vidya ......................................................... 109 11. Taittireya Upanishad ........................................................................................... 117 12. The Three Forms Of God – Viraat, Hiranyagarbha And Avyaakruta .......... 128 13. Spiritual Discipline (sadhana) ............................................................................. 144 14. Dharma And Indian Spirituality ........................................................................ 154 -

Lamotte and the Concept of Anupalabdhi

Lamotte and the concept of anupalabdhi Autor(en): Steinkellner, Ernst Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Asiatische Studien : Zeitschrift der Schweizerischen Asiengesellschaft = Études asiatiques : revue de la Société Suisse-Asie Band (Jahr): 46 (1992) Heft 1: Études bouddhiques offertes à Jacques May PDF erstellt am: 08.10.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-146965 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch LAMOTTE AND THE CONCEPT OF ANUPALABDHI* Ernst Steinkellner, Vienna In his clarification of Etienne Lamotte's position on the issues of the doctrine of non-self, and in answer to Staal's opposition to an earlier remark in the same spirit,1 J.W. -

Brahma Sutra

BRAHMA SUTRA CHAPTER 1 1st Pada 1st Adikaranam to 11th Adhikaranam Sutra 1 to 31 INDEX S. No. Topic Pages Topic No Sutra No Summary 5 Introduction of Brahma Sutra 6 1 Jijnasa adhikaranam 1 a) Sutra 1 103 1 1 2 Janmady adhikaranam 2 a) Sutra 2 132 2 2 3 Sastrayonitv adhikaranam 3 a) Sutra 3 133 3 3 4 Samanvay adhikaranam 4 a) Sutra 4 204 4 4 5 Ikshatyadyadhikaranam: (Sutras 5-11) 5 a) Sutra 5 324 5 5 b) Sutra 6 353 5 6 c) Sutra 7 357 5 7 d) Sutra 8 362 5 8 e) Sutra 9 369 5 9 f) Sutra 10 372 5 10 g) Sutra 11 376 5 11 2 S. No. Topic Pages Topic No Sutra No 6 Anandamayadhikaranam: (Sutras 12-19) 6 a) Sutra 12 382 6 12 b) Sutra 13 394 6 13 c) Sutra 14 397 6 14 d) Sutra 15 407 6 15 e) Sutra 16 411 6 16 f) Sutra 17 414 6 17 g) Sutra 18 416 6 18 h) Sutra 19 425 6 19 7 Antaradhikaranam: (Sutras 20-21) 7 a) Sutra 20 436 7 20 b) Sutra 21 448 7 21 8 Akasadhikaranam : 8 a) Sutra 22 460 8 22 9 Pranadhikaranam : 9 a) Sutra 23 472 9 23 3 S. No. Topic Pages Topic No Sutra No 10 Jyotischaranadhikaranam : (Sutras 24-27) 10 a) Sutra 24 486 10 24 b) Sutra 25 508 10 25 c) Sutra 26 513 10 26 d) Sutra 27 517 10 27 11 Pratardanadhikaranam: (Sutras 28-31) 11 a) Sutra 28 526 11 28 b) Sutra 29 538 11 29 c) Sutra 30 546 11 30 d) Sutra 31 558 11 31 4 SUMMARY Brahma Sutra Bhasyam Topics - 191 Chapter – 1 Chapter – 2 Chapter – 3 Chapter – 4 Samanvaya – Avirodha – non – Sadhana – spiritual reconciliation through Phala – result contradiction practice proper interpretation Topics - 39 Topics - 47 Topics - 67 Topics 38 Sections Topics Sections Topics Sections Topics Sections Topics 1 11 1 13 1 06 1 14 2 07 2 08 2 08 2 11 3 13 3 17 3 36 3 06 4 08 4 09 4 17 4 07 5 Lecture – 01 Puja: • Gratitude to lord for completion of Upanishad course (last Chandogya Upanishad + Brihadaranyaka Upanishad). -

Proof of a Sentient Knower: Utpaladeva's Ajad.Aprama¯T R

J Indian Philos (2009) 37:627–653 DOI 10.1007/s10781-009-9074-z Proof of a Sentient Knower: Utpaladeva’s Ajad:aprama¯t:rsiddhi with the V:rtti of Harabhatta Shastri David Peter Lawrence Published online: 8 October 2009 Ó Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2009 Abstract Utpaladeva (c. 900–950 C.E.) was the chief originator of the Prat- yabhijn˜a¯ philosophical theology of monistic Kashmiri S´aivism, which was further developed by Abhinavagupta (c. 950–1020 C.E.) and other successors. The Ajad:aprama¯t:rsiddhi, ‘‘Proof of a Sentient Knower,’’ is one component of Utp- aladeva’s trio of specialized studies called the Siddhitrayı¯, ‘‘Three Proofs.’’ This article provides an introduction to and translation of the Ajad:aprama¯t:rsiddhi along with the V:rtti commentary on it by the nineteenth–twentieth century pan:d:it, Harabhatta Shastri. Utpaladeva in this work presents ‘‘transcendental’’ arguments that a universal knower (prama¯t:r), the God S´iva, necessarily exists and that this knower is sentient (ajad: a). He defends the Pratyabhijn˜a¯ understanding of sentience against alternative views of both Hindu and Buddhist schools. As elsewhere in his corpus, Utpaladeva also endeavors through his arguments to lead students to the recognition (pratyabhijn˜a¯) of identity with S´iva, properly understood as the sentient knower. Keywords Utpaladeva Á Harabhatta Shastri Á Abhinavagupta Á Ajad:aprama¯t:rsiddhi Á Siddhitrayı¯ Á Pratyabhijn˜a¯ Á prama¯t:r Á praka¯s´a Á svapraka¯s´atva Á Svasam_ vedana Á vimars´a Á prakhya¯ Á upa¯khya¯ Á kart:rta¯ Á ahambha¯va Á vis´ra¯nti Á Knower Á Awareness Á Consciousness Á Self-luminosity Á Self-consciousness Á Recognition Á Agency Á I-hood Á Transcendental argument Á Idealism Á Teleology Abbreviations APS Ajad:aprama¯t:rsiddhi by Utpaladeva APSV Ajad:aprama¯t:rsiddhiv:rtti by Harabhatta Shastri, commentary on APS D. -

Dvaita Vedanta

Dvaita Vedanta Madhva’s Vaisnava Theism K R Paramahamsa Table of Contents Dvaita System Of Vedanta ................................................ 1 Cognition ............................................................................ 5 Introduction..................................................................... 5 Pratyaksa, Sense Perception .......................................... 6 Anumana, Inference ....................................................... 9 Sabda, Word Testimony ............................................... 10 Metaphysical Categories ................................................ 13 General ........................................................................ 13 Nature .......................................................................... 14 Individual Soul (Jiva) ..................................................... 17 God .............................................................................. 21 Purusartha, Human Goal ................................................ 30 Purusartha .................................................................... 30 Sadhana, Means of Attainment ..................................... 32 Evolution of Dvaita Thought .......................................... 37 Madhva Hagiology .......................................................... 42 Works of Madhva-Sarvamula ......................................... 44 An Outline .................................................................... 44 Gitabhashya ................................................................ -

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa Translated into English Prose from the Original Sanskrit Text. By Kisari Mohan Ganguli [1883-1896] TRANSLATOR'S PREFACE The object of a translator should ever be to hold the mirror upto his author. That being so, his chief duty is to represent so far as practicable the manner in which his author's ideas have been expressed, retaining if possible at the sacrifice of idiom and taste all the peculiarities of his author's imagery and of language as well. In regard to translations from the Sanskrit, nothing is easier than to dish up Hindu ideas, so as to make them agreeable to English taste. But the endeavour of the present translator has been to give in the following pages as literal a rendering as possible of the great work of Vyasa. To the purely English reader there is much in the following pages that will strike as ridiculous. Those unacquainted with any language but their own are generally very exclusive in matters of taste. Having no knowledge of models other than what they meet with in their own tongue, the standard they have formed of purity and taste in composition must necessarily be a narrow one. The translator, however, would ill-discharge his duty, if for the sake of avoiding ridicule, he sacrificed fidelity to the original. He must represent his author as he is, not as he should be to please the narrow taste of those entirely unacquainted with him. Mr. Pickford, in the preface to his English translation of the Mahavira Charita, ably defends a close adherence to the original even at the sacrifice of idiom and taste against the claims of what has been called 'Free Translation,' which means dressing the author in an outlandish garb to please those to whom he is introduced. -

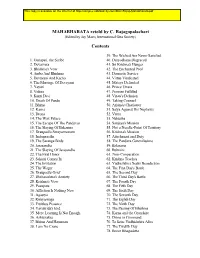

Rajaji-Mahabharata.Pdf

MAHABHARATA retold by C. Rajagopalachari (Edited by Jay Mazo, International Gita Society) Contents 39. The Wicked Are Never Satisfied 1. Ganapati, the Scribe 40. Duryodhana Disgraced 2. Devavrata 41. Sri Krishna's Hunger 3. Bhishma's Vow 42. The Enchanted Pool 4. Amba And Bhishma 43. Domestic Service 5. Devayani And Kacha 44. Virtue Vindicated 6. The Marriage Of Devayani 45. Matsya Defended 7. Yayati 46. Prince Uttara 8. Vidura 47. Promise Fulfilled 9. Kunti Devi 48. Virata's Delusion 10. Death Of Pandu 49. Taking Counsel 11. Bhima 50. Arjuna's Charioteer 12. Karna 51. Salya Against His Nephews 13. Drona 52. Vritra 14. The Wax Palace 53. Nahusha 15. The Escape Of The Pandavas 54. Sanjaya's Mission 16. The Slaying Of Bakasura 55. Not a Needle-Point Of Territory 17. Draupadi's Swayamvaram 56. Krishna's Mission 18. Indraprastha 57. Attachment and Duty 19. The Saranga Birds 58. The Pandava Generalissimo 20. Jarasandha 59. Balarama 21. The Slaying Of Jarasandha 60. Rukmini 22. The First Honor 61. Non-Cooperation 23. Sakuni Comes In 62. Krishna Teaches 24. The Invitation 63. Yudhishthira Seeks Benediction 25. The Wager 64. The First Day's Battle 26. Draupadi's Grief 65. The Second Day 27. Dhritarashtra's Anxiety 66. The Third Day's Battle 28. Krishna's Vow 67. The Fourth Day 29. Pasupata 68. The Fifth Day 30. Affliction Is Nothing New 69. The Sixth Day 31. Agastya 70. The Seventh Day 32. Rishyasringa 71. The Eighth Day 33. Fruitless Penance 72. The Ninth Day 34. Yavakrida's End 73.