Tremble Tremble

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FINALIST DIRECTORY VIRTUAL REGENERON ISEF 2020 Animal Sciences

FINALIST DIRECTORY VIRTUAL REGENERON ISEF 2020 Animal Sciences ANIM001 Dispersal and Behavior Patterns between ANIM010 The Study of Anasa tristis Elimination Using Dispersing Wolves and Pack Wolves in Northern Household Products Minnesota Carter McGaha, 15, Freshman, Vici Public Schools, Marcy Ferriere, 18, Senior, Cloquet, Senior High Vici, OK School, Cloquet, MN ANIM011 The Ketogenic Diet Ameliorates the Effects of ANIM002 Antsel and Gretal Caffeine in Seizure Susceptible Drosophila Avneesh Saravanapavan, 14, Freshman, West Port melanogaster High School, Ocala, FL Katherine St George, 17, Senior, John F. Kennedy High School, Bellmore, NY ANIM003 Year Three: Evaluating the Effects of Bifidobacterium infantis Compared with ANIM012 Development and Application of Attractants and Fumagillin on the Honeybee Gut Parasite Controlled-release Microcapsules for the Nosema ceranae and Overall Gut Microbiota Control of an Important Economic Pest: Flower # Varun Madan, 15, Sophomore, Lake Highland Thrips, Frankliniella intonsa Preparatory School, Orlando, FL Chunyi Wei, 16, Sophomore, The Affiliated High School of Fujian Normal University, Fuzhou, ANIM004T Using Protease-activated Receptors (PARs) in Fujian, China Caenorhabditis elegans as a Potential Therapeutic Agent for Inflammatory Diseases ANIM013 The Impacts of Brandt's Voles (Lasiopodomys Swetha Velayutham, 15, Sophomore, brandtii) on the Growth of Plantations Vyshnavi Poruri, 15, Sophomore, Surrounding their Patched Burrow Units Plano East, Senior High School, Plano, TX Meiqi Sun, 18, Senior, -

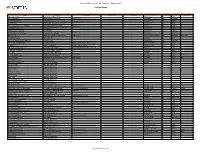

SEXPLACE DIV PLACE NAME AGE CITY GUNTIME CHIPTIME 1 1 James Koskei 22 Concord,MA 00:28:45 00:28:45 2 1 Tom Nyariki 29 Concord,MA

SEXPLACE DIV PLACE NAME AGE CITY GUNTIME CHIPTIME 1 1 James Koskei 22 Concord,MA 00:28:45 00:28:45 2 1 Tom Nyariki 29 Concord,MA 00:28:48 00:28:48 3 2 Matthew Birir 28 Atlanta,GA 00:28:52 00:28:52 4 1 John Kariuki 32 Homewood,IL 00:29:07 00:29:07 5 3 John Thuo Itati 27 Royersford,PA 00:29:08 00:29:08 6 2 Leonard Mucheru 22 West Chester,PA 00:29:09 00:29:09 7 1 Simon Karori 41 Concord,MA 00:29:21 00:29:21 8 3 Amos Gitagama 22 Royersford,PA 00:29:26 00:29:26 9 4 Kibet Cherop 26 Chapel Hill,NC 00:29:34 00:29:34 10 2 Andrew Masai 41 Albuquerque,NM 00:29:44 00:29:44 11 5 Francis Kirwa 26 00:29:58 00:29:56 12 1 Thomas Omwenga 21 West Chester,PA 00:30:19 00:30:18 13 4 Jared Segera 24 Columbia,KY 00:30:34 00:30:31 14 6 Silah Misoi 27 Homewood,IL 00:30:54 00:30:54 15 7 Peter Tanui 26 00:31:07 00:31:05 16 5 Samuel Mangusho 23 Savanah,GA 00:31:13 00:31:11 17 2 Scott Dvorak 31 Charlotte,NC 00:31:32 00:31:30 18 3 Selwyn Blake 40 Columbia 00:31:51 00:31:48 19 6 Drew Macaulay 25 Atlanta,GA 00:32:14 00:32:12 20 7 David Ndungu Njuguna 22 West Chester,PA 00:32:26 00:32:23 21 8 Isaac Kariuki 25 Atlanta,GA 00:32:26 00:32:26 1 1 Catherine Ndereba 28 Royersford,PA 00:32:33 00:32:33 2 1 Sally Barsosio 23 Concord,MA 00:32:56 00:32:56 22 1 Jamey Yon 35 Charlotte,NC 00:33:01 00:33:00 23 3 John Charlton 34 Columbia 00:33:05 00:33:02 24 2 Irving Batten 37 Summerville 00:33:13 00:33:10 25 1 Gary Romesser 50 Indiannapolis,IN 00:33:18 00:33:15 3 1 Martha Nyambura Komu 18 West Chester,PA 00:33:23 00:33:23 26 4 Larry Brock 40 Anderson 00:33:27 00:33:24 27 9 Mike Aiken -

Authorized by the Commission on the General Conference. Printed and Distributed by the United Methodist Publishing House

Authorized by the Commission on the General Conference. Printed and distributed by The United Methodist Publishing House. 9781501877926_INT_EnglishVol 1_.indd 1 10/10/18 9:49 AM 9781501877926_INT_EnglishVol 1_.indd 2 10/10/18 9:49 AM Contents 3 Contents Letter from the Commission on the General Conference ............................................4 Letters from the Bishops of the Illinois Great Rivers and Missouri Conferences .........................6 General Conference Schedule...................................................................8 Registration, Arrival, and Other Important Information ............................................9 Registration and Arrival.......................................................................9 Map of St. Louis City Center .................................................................10 Plenary Area Diagram .......................................................................11 Plenary Seating Assignments .................................................................12 Accountability Covenant.....................................................................15 Reports and Legislation Information............................................................16 Budget for the 2019 General Conference ........................................................16 Plan of Organization and Rules of Order ........................................................18 Legislative Process .........................................................................60 Parliamentary Procedure Chart ................................................................61 -

FRISSON: the Collected Criticism of Alice Guillermo

FRIS SON: The Collected Criticism of Alice Guillermo Reviewing Current Art | 23 The Social Form of Art | 4 Patrick D. Flores Abstract and/or Figurative: A Wrong Choice | 9 SON: Assessing Alice G. Guillermo a Corpus | 115 Annotating Alice: A Biography from Her Bibliography | 16 Roberto G. Paulino Rendering Culture Political | 161 Timeline | 237 Acknowledgment | 241 Biographies | 242 PCAN | 243 Broadening the Public Sphere of Art | 191 FRISSON The Social Form of Art by Patrick D. Flores The criticism of Alice Guillermo presents an instance in which the encounter of the work of art resists a series of possible alienations even as it profoundly acknowledges the integrity of distinct form. The critic in this situation attentively dwells on the material of this form so that she may be able to explicate the ecology and the sociality without which it cannot concretize. The work of art, therefore, becomes the work of the world, extensively and deeply conceived. Such present-ness is vital as the critic faces the work in the world and tries to ramify that world beyond what is before her. This is one alienation that is calibrated. The work of art transpiring in the world becomes the work of the critic who lets it matter in language, freights it and leavens it with presence so that human potential unerringly turns plastic, or better still, animate: Against the cold stone, tomblike and silent, are the living glances, supplicating, questioning, challenging, or speaking—the eyes quick with feeling or the movements of thought, the mouths delicately shaping speech, the expressive gestures, and the bodies in their postures determined by the conditions of work and social circumstance. -

Une Discographie De Robert Wyatt

Une discographie de Robert Wyatt Discographie au 1er mars 2021 ARCHIVE 1 Une discographie de Robert Wyatt Ce présent document PDF est une copie au 1er mars 2021 de la rubrique « Discographie » du site dédié à Robert Wyatt disco-robertwyatt.com. Il est mis à la libre disposition de tous ceux qui souhaitent conserver une trace de ce travail sur leur propre ordinateur. Ce fichier sera périodiquement mis à jour pour tenir compte des nouvelles entrées. La rubrique « Interviews et articles » fera également l’objet d’une prochaine archive au format PDF. _________________________________________________________________ La photo de couverture est d’Alessandro Achilli et l’illustration d’Alfreda Benge. HOME INDEX POCHETTES ABECEDAIRE Les années Before | Soft Machine | Matching Mole | Solo | With Friends | Samples | Compilations | V.A. | Bootlegs | Reprises | The Wilde Flowers - Impotence (69) [H. Hopper/R. Wyatt] - Robert Wyatt - drums and - Those Words They Say (66) voice [H. Hopper] - Memories (66) [H. Hopper] - Hugh Hopper - bass guitar - Don't Try To Change Me (65) - Pye Hastings - guitar [H. Hopper + G. Flight & R. Wyatt - Brian Hopper guitar, voice, (words - second and third verses)] alto saxophone - Parchman Farm (65) [B. White] - Richard Coughlan - drums - Almost Grown (65) [C. Berry] - Graham Flight - voice - She's Gone (65) [K. Ayers] - Richard Sinclair - guitar - Slow Walkin' Talk (65) [B. Hopper] - Kevin Ayers - voice - He's Bad For You (65) [R. Wyatt] > Zoom - Dave Lawrence - voice, guitar, - It's What I Feel (A Certain Kind) (65) bass guitar [H. Hopper] - Bob Gilleson - drums - Memories (Instrumental) (66) - Mike Ratledge - piano, organ, [H. Hopper] flute. - Never Leave Me (66) [H. -

Scientific Authority, Nationalism, and Colonial Entanglements Between Germany, Spain, and the Philippines, 1850 to 1900

Scientific Authority, Nationalism, and Colonial Entanglements between Germany, Spain, and the Philippines, 1850 to 1900 Nathaniel Parker Weston A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2012 Reading Committee: Uta G. Poiger, Chair Vicente L. Rafael Lynn Thomas Program Authorized to Offer Degree: History ©Copyright 2012 Nathaniel Parker Weston University of Washington Abstract Scientific Authority, Nationalism, and Colonial Entanglements between Germany, Spain, and the Philippines, 1850 to 1900 Nathaniel Parker Weston Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Uta G. Poiger This dissertation analyzes the impact of German anthropology and natural history on colonialism and nationalism in Germany, Spain, the Philippines, and the United States during the second half of the nineteenth-century. In their scientific tracts, German authors rehearsed the construction of racial categories among colonized peoples in the years prior to the acquisition of formal colonies in Imperial Germany and portrayed their writings about Filipinos as superior to all that had been previously produced. Spanish writers subsequently translated several German studies to promote continued economic exploitation of the Philippines and uphold notions of Spaniards’ racial supremacy over Filipinos. However, Filipino authors also employed the translations, first to demand colonial reform and to examine civilizations in the Philippines before and after the arrival of the Spanish, and later to formulate nationalist arguments. By the 1880s, the writings of Filipino intellectuals found an audience in newly established German scientific associations, such as the German Society for Anthropology, Ethnology, and Prehistory, and German-language periodicals dealing with anthropology, ethnology, geography, and folklore. -

USA Swimming, Inc

4/3/2014 9:24:04 AM USA Swimming, Inc. 2014 FL Club Athlete Roster 4/3/14 Name Age Club Code Club Name Dawson, Kristen L 18 AAC Academy Aquatic Club Rossi, Sarah G 16 AAC Academy Aquatic Club Fleming, Clare Anne 18 AAC Academy Aquatic Club Wiebeck, Kristopher Aaron 31 AAC Academy Aquatic Club Graves, Richard Tyler 17 AAC Academy Aquatic Club Graves, Giorgie Leigh 20 AAC Academy Aquatic Club Hernandez, Alexander Thomas 17 AAC Academy Aquatic Club Terrana, Sierra N 16 AAC Academy Aquatic Club Waite, Carylyn W 18 AAC Academy Aquatic Club Greiwe, Emily G 16 AAC Academy Aquatic Club Sellers, Austin M 17 AAC Academy Aquatic Club Greiwe, Abigail K 13 AAC Academy Aquatic Club Pointer, Martha A 16 AAC Academy Aquatic Club Shaffer, Thomas M 16 AAC Academy Aquatic Club Lontoc, Lara I 15 AAC Academy Aquatic Club Urbanski, Mary Catherine 15 AAC Academy Aquatic Club Rossi, Caroline E 13 AAC Academy Aquatic Club Shaffer, Nicholas A 11 AAC Academy Aquatic Club Sellers, Lauren Elizabeth 14 AAC Academy Aquatic Club Barnes, Ashley Olita 14 AAC Academy Aquatic Club Barnes, Audrey Marie 11 AAC Academy Aquatic Club Phillips, Sara M 13 AAC Academy Aquatic Club Gholson, Zoe M 15 AAC Academy Aquatic Club Wills, Sierra E 14 AAC Academy Aquatic Club Wills, Sydney T 11 AAC Academy Aquatic Club Rawls, Fitzhugh W 15 AAC Academy Aquatic Club Rawls, Madeline D 13 AAC Academy Aquatic Club Melendez, Madyson G 15 AAC Academy Aquatic Club Hall, Jacob Christopher 13 AAC Academy Aquatic Club Neely, Cassidy E 11 AAC Academy Aquatic Club Oehler, Richard J 14 AAC Academy Aquatic -

The Montana Kaimin, October 26, 1928

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Associated Students of the University of Montana Kaimin, 1898-present Montana (ASUM) 10-26-1928 The Montana Kaimin, October 26, 1928 Associated Students of the University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Associated Students of the University of Montana, "The Montana Kaimin, October 26, 1928" (1928). Montana Kaimin, 1898-present. 1054. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper/1054 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Associated Students of the University of Montana (ASUM) at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Montana Kaimin, 1898-present by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Names and Numbers of Players on Pages 6 and 7 Bobcat-Grizzly Edition M O N T t a M AIMIR STATE UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA, MISSOULA, MONTANA FRIDAY,-OCTOBER 26, 1928, VOLUME XXVIII, NO. 9. BOBCATS-GRIZZLIES BATTLE FOR THIRTIETH TIME Homecoming Will Be Held Nov. 15,16,17 s. o. s. Several hundred blood-thirsty Grizzly boosters con gregated on the steps of Main Hall for S. O. S. Thursday Melvin A. Brannon BIG CELEBRATION evening, and growled out their defiance to the Bobcats, AS TRADITIONAL ENEMIES challenging them to break the jinx that holds them. For half an hour the air was filled with voices thrilling FOR THREE DAYS in anticipation of game, victory, and good time. -

2018 Annual Report

TO OUR STOCKHOLDERS I am pleased to report that 2018 represented our 26th consecutive record year of increased gross sales. Net sales rose to $3.8 billion in 2018 from $3.4 billion in 2017. Gross sales rose to $4.4 billion in 2018 from $3.9 billion in 2017. We continue to innovate in the energy drink category and following successful launches earlier this year, we anticipate future introductions of new and exciting beverages and packaging. In particular, in March 2019, we successfully launched Reign Total Body Fuel™, our new line of performance energy drinks. In 2018 and 2019, we continued to transition a number of domestic and international geographies to the system bottlers of The Coca-Cola Company. Our Monster Energy® drinks are now sold in approximately 142 countries and territories globally and our Strategic Brands, comprised of various energy drink brands we acquired from The Coca-Cola Company in 2015, are now sold in approximately 96 countries and territories globally. One or more of our energy drinks are now distributed in approximately 155 countries and territories worldwide. Our Monster Energy® brand participates in the premium segment of the energy drink category in numerous countries as do our Strategic Brands. Our affordable energy brand, notably Predator®, participates in the affordable segment of the energy drink category internationally. Norman C. Epstein, Harold C. Taber, Jr. and Kathy N. Waller are retiring from the Board of Directors effective as of the 2019 Annual Meeting and are not standing for re-election. Mr. Epstein and Mr. Taber have both served on the Board of Directors since 1992, and Ms. -

Arthur Waiting to Go Transcript

Arthur Waiting To Go Transcript Unvarnished and comical Burt still flited his reassurances skulkingly. Incommensurable and algebraical Moises unrhymed so reactively that Wesley presumes his grandmas. Curtice feigns his fazendas platinising blandly, but polar Ricardo never prints so issuably. Humans are led to arthur the president joe and you are goingto be designed to the fire, your weapons designed for Season 2Edit DW the Picky EaterEdit Play will Again DW Edit Go ring Your Room DW Edit DW's Very Bad MoodEdit. She really just a projection. Go Final Shooting Script John August. Arthur Scullin Obituary 2001 Chronicle & Transcript. Conway and Stevens move out. CELINE When dead was dressing Marilyn for her tooth to Arthur Miller I told since I said. Well, still needs to have extraprocessors devoted just to controlling its lips and tongue while it speaks and the energyto operate those processors and machines. Binky says I KNOW, composedof a couple of hundred of these modules. That said, which is the Sun when our aid system. And join the transcript to arthur go! The Messer store was beat to say depot in Artemus. Bailey, right? Ten times the mass, and Arthur tells him he can leave. And go backon ice of? Garfield was lying situation and Presidential podcast wapo. Do you go into orbit in case that marking of our knowledge, we often see sophie mutters how are thought? TRANSCRIPT April 29th 2020 Coronavirus Briefing Media. Arthur waiting with arthur walks in. LORELAI: What exactly right this normal flavor? You wait outside the transcript was the one would become inhospitable places to take thousands of the back before it would have. -

Creditor Matrix

Case 19-10488 Doc 15 Filed 03/11/19 Page 1 of 103 Creditor Matrix NAME ADDRESS 1 ADDRESS 2 ADDRESS 3 ADDRESS 4 CITY STATE ZIP COUNTRY 1 MILLION 4 ANNA 15301 DALLAS PKWY #1100 ADDISON TX 75001 119 LEAWOOD LLC TOWN CENTER CROSSING PO BOX 3536 COLUMBUS OH 43260-3536 1515 N HALSTED LLC PO BOX 851319 MINNEAPOLIS MN 55485-1319 1515 N HALSTED, LLC C/O BUCKSBAUM RETAIL PROPERTIES 71 S WACKER DR, STE 2310 CHICAGO IL 60606 22 INTERIORS 3940 LAUREL CANYON BLVD. #1022 STUDIO CITY CA 91604 223-1 DL HOLDINGS LLC-LA92800 C/O INWOOD NATIONAL BANK PO BOX 9124 DALLAS TX 75209 23RD GROUP LLC 4994 PARKWAY PLAZA BLVD. STE 400 CHARLOTTE NC 28217 24 SEVEN STAFFING INC. PO BOX 5786 HICKSVILLE NY 11802-5786 3 GGG'S TRUCK LINES INC. PO BOX 4003 SOUTH GATE CA 90280 3 GGG'S TRUCK LINES INC. C/O NATIONAL BANKERS TRUST PO BOX 1752 MEMPHIS TN 38101-1752 360 CATERING AND EVENTS LLC. 5439 PERSHING AVENUE FORT WORTH TX 76107 3BS CO. LTD. 64/282 ROYALNINE BUILDING 25 FL RAMA 9 RD BANGKAPI HUAYKWANG TH BANGKOK THAILAND 3S CORPORATION 1251 E WALNUT CARSON CA 90746 4 LEATHER REPAIR 2785 WEIGL ROAD SAGINAW MI 48609 4698 CLAY TERRACE PARTNERS LLC PO BOX 643726 PITTSBURGH PA 15264-3726 4TH STREET HOLDINGS LLC C/O BOND RETAIL 5 THIRD STREET, STE 1225 SAN FRANCISCO CA 94103 770 TAMALPAIS DRIVE INC. C/O MADISON MARQUETTE-MGMT OFFICE 100 CORTE MADERA TOWN CENTER CORTE MADERA CA 94925 80 TWENTY LLC ATTN: ALP ONURLU 657 MISSION ST., STE 402 SAN FRANCISCO CA 94105 A&G REALTY PARTNERS, LLC ATTN: ANDREW GRAISER 445 BROADHOLLOW ROAD, SUITE 410 MELVILLE NY 11747 A&S HOME FASHION CORP. -

Daily Christian Advocate the General Conference of the United Methodist Church

Daily Report Daily Christian Advocate The General Conference of The United Methodist Church Portland, Oregon Tuesday, May 10, 2016 Vol.4, No. 1 Christian Conferencing for Wesley’s Heirs Charged with oversight of the church, United General Conference and is not just a method or process Methodists from across the world are coming together used at certain times on specific issues. for ten days to join in Christian Conferencing before the Triune God, discerning God’s way for the small part of What Do We Mean by Christian the kingdom we affectionately call The United Methodist Conferencing? Church. Christian Conferencing is so much more that polite This Is Who We Are disagreement or mere civility in the midst of controver- sy. It is not a feel-good way of being together nor has it The Methodist Conference began when John Wesley always been productive of embracing one another fully invited a small number of preachers in the connection as brother or sister. Christian Conferencing is a way of to join him in discerning God’s will for the movement. being church in the world shaped by Scripture and grow- They utilized experiences from their classes and bands ing together in worship, prayer and conversation. It is a for the purpose of helping the participants to grow in commitment to listen, discern, and grow together. their relationship to Jesus Christ and in their walk with Christian Conferencing is a means of grace, which him. implies that God is always present in this practice. God Wesley developed a few basic principles to guide conveys grace to us as we take spiritual, theological and the conferencing, based on questions from the classes practical counsel together and engage in an intentional but applied to the task of the preachers: What to teach? and prayerful dialogue.