Germany and the EU Constitutional Debate March 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dr. Otto Graf Lambsdorff F.D.P

Plenarprotokoll 13/52 Deutscher Bundestag Stenographischer Bericht 52. Sitzung Bonn, Donnerstag, den 7. September 1995 Inhalt: Zur Geschäftsordnung Dr. Uwe Jens SPD 4367 B Dr. Peter Struck SPD 4394B, 4399A Dr. Otto Graf Lambsdorff F.D.P. 4368B Joachim Hörster CDU/CSU 4395 B Kurt J. Rossmanith CDU/CSU . 4369 D Werner Schulz (Berlin) BÜNDNIS 90/DIE Dr. Norbert Blüm, Bundesminister BMA 4371 D GRÜNEN 4396 C Rudolf Dreßler SPD 4375 B Jörg van Essen F.D.P. 4397 C Eva Bulling-Schröter PDS 4397 D Dr. Gisela Babel F.D.P 4378 A Marieluise Beck (Bremen) BÜNDNIS 90/ Tagesordnungspunkt 1 (Fortsetzung): DIE GRÜNEN 4379 C a) Erste Beratung des von der Bundesre- Hans-Joachim Fuchtel CDU/CSU . 4380 C gierung eingebrachten Entwurfs eines Rudolf Dreßler SPD 4382A Gesetzes über die Feststellung des Annelie Buntenbach BÜNDNIS 90/DIE Bundeshaushaltsplans für das Haus- GRÜNEN 4384 A haltsjahr 1996 (Haushaltsgesetz 1996) (Drucksache 13/2000) Dr. Gisela Babel F.D.P 4386B Manfred Müller (Berlin) PDS 4388B b) Beratung der Unterrichtung durch die Bundesregierung Finanzplan des Bun- Ulrich Heinrich F D P. 4388 D des 1995 bis 1999 (Drucksache 13/2001) Ottmar Schreiner SPD 4390 A Dr. Günter Rexrodt, Bundesminister BMWi 4345 B Dr. Norbert Blüm CDU/CSU 4390 D - Ernst Schwanhold SPD . 4346D, 4360 B Gerda Hasselfeldt CDU/CSU 43928 Anke Fuchs (Köln) SPD 4349 A Dr. Jürgen Rüttgers, Bundesminister BMBF 4399B Dr. Hermann Otto Solms F.D.P. 4352A Doris Odendahl SPD 4401 D Birgit Homburger F D P. 4352 C Günter Rixe SPD 4401 D Ernst Hinsken CDU/CSU 4352B, 4370D, 4377 C Dr. -

H.E. Ms. Angela Merkel, Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany, Addresses 100Th International Labour Conference

H.E. Ms. Angela Merkel, Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany, Addresses 100th International Labour Conference In the first ever visit of a German Chancellor to the International Labour Organisation (ILO), H.E. Ms. Angela Merkel today addressed the Organization’s annual conference. Speaking to the historic 100th session of the International Labour Conference (ILC) Ms Merkel highlighted the increasing role played by the ILO in closer international cooperation. The G8 and G20 meetings would be “unthinkable without the wealth of experience of this Organisation”, she said, adding that the ILO’s involvement was the only way “to give globalization a form, a structure” (In German with subtitles in English). Transcription in English: Juan Somavia, Director-General, International Labour Organization: “Let me highlight your distinctive sense of policy coherence. Since 2007, you have regularly convened in Berlin the heads of the IMF, World Bank, WTO, OECD and the ILO, and urged us to strengthen our cooperation, and this with a view to building a strong social dimension of globalization and greater policy coherence among our mandates. These dialogues, under your guidance, have been followed up actively by the ILO with important joint initiatives with all of them, whose leaders have all addressed the Governing Body of the ILO. You have been a strong voice for a fairer, more balanced globalization in which much needs to be done by all international organizations.” Angela Merkel, Chancellor of Germany: “Universal and lasting peace can be established only if it is based on social justice.” This is the first sentence of the Constitution of the ILO and I also wish to start my speech with these words, as they clearly express what the ILO is all about and what it is trying to achieve: universal peace. -

Deutscher Bundestag

Deutscher Bundestag 44. Sitzung des Deutschen Bundestages am Freitag, 27.Juni 2014 Endgültiges Ergebnis der Namentlichen Abstimmung Nr. 4 Entschließungsantrag der Abgeordneten Caren Lay, Eva Bulling-Schröter, Dr. Dietmar Bartsch, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion DIE LINKE. zu der dritten Beratung des Gesetzentwurfs der Bundesregierung Entwurf eines Gesetzes zur grundlegenden Reform des Erneuerbare-Energien-Gesetzes und zur Änderung weiterer Bestimmungen des Energiewirtschaftsrechts - Drucksachen 18/1304, 18/1573, 18/1891 und 18/1901 - Abgegebene Stimmen insgesamt: 575 Nicht abgegebene Stimmen: 56 Ja-Stimmen: 109 Nein-Stimmen: 465 Enthaltungen: 1 Ungültige: 0 Berlin, den 27.06.2014 Beginn: 10:58 Ende: 11:01 Seite: 1 Seite: 2 Seite: 2 CDU/CSU Name Ja Nein Enthaltung Ungült. Nicht abg. Stephan Albani X Katrin Albsteiger X Peter Altmaier X Artur Auernhammer X Dorothee Bär X Thomas Bareiß X Norbert Barthle X Julia Bartz X Günter Baumann X Maik Beermann X Manfred Behrens (Börde) X Veronika Bellmann X Sybille Benning X Dr. Andre Berghegger X Dr. Christoph Bergner X Ute Bertram X Peter Beyer X Steffen Bilger X Clemens Binninger X Peter Bleser X Dr. Maria Böhmer X Wolfgang Bosbach X Norbert Brackmann X Klaus Brähmig X Michael Brand X Dr. Reinhard Brandl X Helmut Brandt X Dr. Ralf Brauksiepe X Dr. Helge Braun X Heike Brehmer X Ralph Brinkhaus X Cajus Caesar X Gitta Connemann X Alexandra Dinges-Dierig X Alexander Dobrindt X Michael Donth X Thomas Dörflinger X Marie-Luise Dött X Hansjörg Durz X Jutta Eckenbach X Dr. Bernd Fabritius X Hermann Färber X Uwe Feiler X Dr. Thomas Feist X Enak Ferlemann X Ingrid Fischbach X Dirk Fischer (Hamburg) X Axel E. -

Beyond Social Democracy in West Germany?

BEYOND SOCIAL DEMOCRACY IN WEST GERMANY? William Graf I The theme of transcending, bypassing, revising, reinvigorating or otherwise raising German Social Democracy to a higher level recurs throughout the party's century-and-a-quarter history. Figures such as Luxemburg, Hilferding, Liebknecht-as well as Lassalle, Kautsky and Bernstein-recall prolonged, intensive intra-party debates about the desirable relationship between the party and the capitalist state, the sources of its mass support, and the strategy and tactics best suited to accomplishing socialism. Although the post-1945 SPD has in many ways replicated these controversies surrounding the limits and prospects of Social Democracy, it has not reproduced the Left-Right dimension, the fundamental lines of political discourse that characterised the party before 1933 and indeed, in exile or underground during the Third Reich. The crucial difference between then and now is that during the Second Reich and Weimar Republic, any significant shift to the right on the part of the SPD leader- ship,' such as the parliamentary party's approval of war credits in 1914, its truck under Ebert with the reactionary forces, its periodic lapses into 'parliamentary opportunism' or the right rump's acceptance of Hitler's Enabling Law in 1933, would be countered and challenged at every step by the Left. The success of the USPD, the rise of the Spartacus move- ment, and the consistent increase in the KPD's mass following throughout the Weimar era were all concrete and determined reactions to deficiences or revisions in Social Democratic praxis. Since 1945, however, the dynamics of Social Democracy have changed considerably. -

Dr. Peter Gauweiler (CDU/CSU)

Inhaltsverzeichnis Plenarprotokoll 18/9 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 9. Sitzung Berlin, Freitag, den 17. Januar 2014 Inhalt: Tagesordnungspunkt 15: Tagesordnungspunkt 16: Vereinbarte Debatte: zum Arbeitsprogramm Antrag der Abgeordneten Ulla Jelpke, Jan der Europäischen Kommission . 503 B Korte, Katrin Kunert, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion DIE LINKE: Das Massen- Axel Schäfer (Bochum) (SPD) . 503 B sterben an den EU-Außengrenzen been- Alexander Ulrich (DIE LINKE) . 505 A den – Für eine offene, solidarische und hu- mane Flüchtlingspolitik der Europäischen Gunther Krichbaum (CDU/CSU) . 506 C Union Drucksache 18/288 . 524 D Manuel Sarrazin (BÜNDNIS 90/ DIE GRÜNEN) . 508 C Ulla Jelpke (DIE LINKE) . 525 A Michael Roth, Staatsminister Charles M. Huber (CDU/CSU) . 525 D AA . 510 A Thomas Silberhorn (CDU/CSU) . 528 A Britta Haßelmann (BÜNDNIS 90/ DIE GRÜNEN) . 510 C Luise Amtsberg (BÜNDNIS 90/ DIE GRÜNEN) . 530 A Andrej Hunko (DIE LINKE) . 511 D Christina Kampmann (SPD) . 532 A Manuel Sarrazin (BÜNDNIS 90/ DIE GRÜNEN) . 512 B Wolfgang Gehrcke (DIE LINKE) . 533 D Detlef Seif (CDU/CSU) . 513 A Stephan Mayer (Altötting) (CDU/CSU) . 534 D Dr. Diether Dehm (DIE LINKE) . 513 C Volker Beck (Köln) (BÜNDNIS 90/ DIE GRÜNEN) . 535 C Annalena Baerbock (BÜNDNIS 90/ DIE GRÜNEN) . 514 D Harald Petzold (Havelland) (DIE LINKE) . 536 A Annalena Baerbock (BÜNDNIS 90/ DIE GRÜNEN) . 515 D Wolfgang Gehrcke (DIE LINKE) . 536 D Dagmar Schmidt (Wetzlar) (SPD) . 517 B Tom Koenigs (BÜNDNIS 90/ DIE GRÜNEN) . 538 A Jürgen Hardt (CDU/CSU) . 518 C Sabine Bätzing-Lichtenthäler (SPD) . 539 A Norbert Spinrath (SPD) . 520 C Marian Wendt (CDU/CSU) . 540 C Dr. Peter Gauweiler (CDU/CSU) . -

To Chancellor Dr. Angela Merkel C/O Minister of Finance Dr. Wolfgang Schäuble C/O Vice Chancellor Sigmar Gabriel

To Chancellor Dr. Angela Merkel c/o Minister of Finance Dr. Wolfgang Schäuble c/o Vice Chancellor Sigmar Gabriel Dear Chancellor Merkel, We, the undersigned organisations from [XX] European countries are very grateful for your commitment to the financial transaction tax (FTT) in the framework of Enhanced Coopera- tion. Like you, we are of the opinion that only a broad based tax as specified in the coalition agreement and spelt out in the draft of the European Commission will be sufficiently compre- hensive. However, we are concerned that under the pressure of the finance industry some govern- ments will try to water down the proposal of the Commission. Particularly problematic would be to exempt derivatives from taxation or to tax only some of them. Derivatives represent the biggest share of transactions on the financial markets. Hence, exemptions would lead imme- diately to a substantial reduction of tax revenues. Furthermore, many derivatives are the source of dangerous stability risks and would be misused as instruments for the avoidance of the taxation of shares and bonds. We therefore ask you not to give in to the pressure of the finance industry and to tax deriva- tives as put forward in the draft proposal of the Commission. The primacy of politics over financial markets must be restored. In addition we would like to ask you to send a political signal with regard to the use of the tax revenues. We know that the German budget law does not allow the assignment of tax reve- nues for a specific purpose. However, you yourself have already stated that you could envis- age the revenues being used partly to combat youth unemployment in Europe. -

What Does GERMANY Think About Europe?

WHat doEs GERMaNY tHiNk aboUt europE? Edited by Ulrike Guérot and Jacqueline Hénard aboUt ECFR The European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) is the first pan-European think-tank. Launched in October 2007, its objective is to conduct research and promote informed debate across Europe on the development of coherent, effective and values-based European foreign policy. ECFR has developed a strategy with three distinctive elements that define its activities: •a pan-European Council. ECFR has brought together a distinguished Council of over one hundred Members - politicians, decision makers, thinkers and business people from the EU’s member states and candidate countries - which meets once a year as a full body. Through geographical and thematic task forces, members provide ECFR staff with advice and feedback on policy ideas and help with ECFR’s activities within their own countries. The Council is chaired by Martti Ahtisaari, Joschka Fischer and Mabel van Oranje. • a physical presence in the main EU member states. ECFR, uniquely among European think-tanks, has offices in Berlin, London, Madrid, Paris, Rome and Sofia. In the future ECFR plans to open offices in Warsaw and Brussels. Our offices are platforms for research, debate, advocacy and communications. • a distinctive research and policy development process. ECFR has brought together a team of distinguished researchers and practitioners from all over Europe to advance its objectives through innovative projects with a pan-European focus. ECFR’s activities include primary research, publication of policy reports, private meetings and public debates, ‘friends of ECFR’ gatherings in EU capitals and outreach to strategic media outlets. -

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Case Log October 2000 - April 2002

Description of document: Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Case Log October 2000 - April 2002 Requested date: 2002 Release date: 2003 Posted date: 08-February-2021 Source of document: Information and Privacy Coordinator Central Intelligence Agency Washington, DC 20505 Fax: 703-613-3007 Filing a FOIA Records Request Online The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is a First Amendment free speech web site and is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. 1 O ct 2000_30 April 2002 Creation Date Requester Last Name Case Subject 36802.28679 STRANEY TECHNOLOGICAL GROWTH OF INDIA; HONG KONG; CHINA AND WTO 36802.2992 CRAWFORD EIGHT DIFFERENT REQUESTS FOR REPORTS REGARDING CIA EMPLOYEES OR AGENTS 36802.43927 MONTAN EDWARD GRADY PARTIN 36802.44378 TAVAKOLI-NOURI STEPHEN FLACK GUNTHER 36810.54721 BISHOP SCIENCE OF IDENTITY FOUNDATION 36810.55028 KHEMANEY TI LEAF PRODUCTIONS, LTD. -

Der Imagewandel Von Helmut Kohl, Gerhard Schröder Und Angela Merkel Vom Kanzlerkandidaten Zum Kanzler - Ein Schauspiel in Zwei Akten

Forschungsgsgruppe Deutschland Februar 2008 Working Paper Sybille Klormann, Britta Udelhoven Der Imagewandel von Helmut Kohl, Gerhard Schröder und Angela Merkel Vom Kanzlerkandidaten zum Kanzler - Ein Schauspiel in zwei Akten Inszenierung und Management von Machtwechseln in Deutschland 02/2008 Diese Veröffentlichung entstand im Rahmen eines Lehrforschungsprojektes des Geschwister-Scholl-Instituts für Politische Wissenschaft unter Leitung von Dr. Manuela Glaab, Forschungsgruppe Deutschland am Centrum für angewandte Politikforschung. Weitere Informationen unter: www.forschungsgruppe-deutschland.de Inhaltsverzeichnis: 1. Die Bedeutung und Bewertung von Politiker – Images 3 2. Helmut Kohl: „Ich werde einmal der erste Mann in diesem Lande!“ 7 2.1 Gut Ding will Weile haben. Der „Lange“ Weg ins Kanzleramt 7 2.2 Groß und stolz: Ein Pfälzer erschüttert die Bonner Bühne 11 2.3 Der richtige Mann zur richtigen Zeit: Der Mann der deutschen Mitte 13 2.4 Der Bauherr der Macht 14 2.5 Kohl: Keine Richtung, keine Linie, keine Kompetenz 16 3. Gerhard Schröder: „Ich will hier rein!“ 18 3.1 „Hoppla, jetzt komm ich!“ Schröders Weg ins Bundeskanzleramt 18 3.2 „Wetten ... dass?“ – Regieren macht Spass 22 3.3 Robin Hood oder Genosse der Bosse? Wofür steht Schröder? 24 3.4 Wo ist Schröder? Vom „Gernekanzler“ zum „Chaoskanzler“ 26 3.5 Von Saumagen, Viel-Sagen und Reformvorhaben 28 4. Angela Merkel: „Ich will Deutschland dienen.“ 29 4.1 Fremd, unscheinbar und unterschätzt – Merkels leiser Aufstieg 29 4.2 Die drei P’s der Merkel: Physikerin, Politikerin und doch Phantom 33 4.3 Zwischen Darwin und Deutschland, Kanzleramt und Küche 35 4.4 „Angela Bangbüx“ : Versetzung akut gefährdet 37 4.5 Brutto: Aus einem Guss – Netto: Zuckerguss 39 5. -

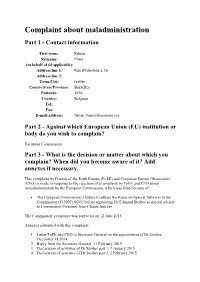

Complaint About Maladministration Part 1 - Contact Information

Complaint about maladministration Part 1 - Contact information First name: Fabian Surname: Flues On behalf of (if applicable): Address line 1: Rue d'Edimbourg 26 Address line 2: Town/City: Ixelles County/State/Province: Bruxelles Postcode: 1050 Country: Belgium Tel.: Fax: E-mail address: [email protected] Part 2 - Against which European Union (EU) institution or body do you wish to complain? European Commission Part 3 - What is the decision or matter about which you complain? When did you become aware of it? Add annexes if necessary. This complaint by Friends of the Earth Europe (FoEE) and Corporate Europe Observatory (CEO) is made in response to the rejection of a complaint by FoEE and CEO about maladministration by the European Commission, which was filed because of: The European Commission’s failure to adhere the Rules on Special Advisers to the Commission (C(2007) 6655) before appointing Dr Edmund Stoiber as special adviser to Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker The Commission’s response was sent to us on 12 June 2015. Annexes submitted with this complaint: 1. Letter FoEE and CEO to Secretary General on the appointment of Dr Stoiber, December 18 2014 2. Reply from the Secretary General, 11 February 2015 3. Declaration of activities of Dr Stoiber part 1, 7 January 2015 4. Declaration of activities of Dr Stoiber part 2, 2 February 2015 5. Declaration of honour of Dr Stoiber 7 January 2015 6. Response Secretary General to FoEE and CEO questions, 16 February 2015 7. Letter FoEE and CEO to Secretary General requesting reconsideration, 25 May 2015 8. -

Ostracized in the West, Elected in the East – the Successors of the SED

Volume 10. One Germany in Europe, 1989 – 2009 The Red Socks (June 24, 1994) The unexpected success of the successor party to the SED, the Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS), at the ballot box in East Germany put the established (Western) parties in a difficult situation: what response was called for, ostracism or integration? The essay analyzes the reasons behind the success of the PDS in the East and the changing party membership. The Party that Lights a Fire Ostracized in the West, voted for in the East – the successors to the SED are drawing surprising support. Discontent over reunification, GDR nostalgia, or a yearning for socialism – what makes the PDS attractive? Last Friday, around 12:30 pm, a familiar ritual began in the Bundestag. When representative Uwe-Jens Heuer of the PDS stepped to the lectern, the parliamentary group of the Union [CDU/CSU] transformed itself into a raging crowd. While Heuer spoke of his party’s SED past, heckling cries rained down on him: “nonsense,” “outrageous.” The PDS makes their competitors’ blood boil, more so than ever. Saxony-Anhalt votes for a new Landtag [state parliament] on Sunday, and the successor to the SED could get twenty percent of the vote. It did similarly well in the European elections in several East German states. In municipal elections, the PDS has often emerged as the strongest faction, for example, in Halle, Schwerin, Rostock, Neubrandenburg, and Hoyerswerda. A specter is haunting East Germany. Is socialism celebrating a comeback, this time in democratic guise? All of the Bonn party headquarters are in a tizzy. -

José Manuel Martínez Sierra The

Zentrum für Europäische Integrationsforschung Center for European Integration Studies Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn D i s c José Manuel Martínez Sierra u s The Spanish Presidency Buying more than it can s i choose? o n P a ISSN 1435-3288 ISBN 3-936183-12-0 p Zentrum für Europäische Integrationsforschung e Center for European Integration Studies Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn r Walter-Flex-Straße 3 Tel.: +49-228-73-1880 D-53113 Bonn Fax: +49-228-73-1788 C 112 Germany http: //www.zei.de 2002 Prof. Dr. D. José Manuel Martínez Sierra, born 1971, is Professor Titular in Constitutional Law at Complutense University of Madrid since February 2002. After studies of Law, Political and Social sci- ence at Madrid, Alcalá and Amsterdam, Martínez Sierra wrote a LL.M dissertation on the European Parliament and a PhD dissertation on the structural problems in the Political System of the EU. He was a trainee at the Council of the EU and lecturer at La Laguna University (2000-2002). His recent publications include: El procedimiento legislativo de la codecisión: de Maastricht a Niza, Valencia 2002; (with A. de Cabo) Constitucionalismo, mundialización y crisis del concepto de sober- anía, Alicante 2000; La reforma constitucional y el referéndum en Irlanda: a propósito de Niza, Teoría y Realidad Constitucional, n° 7 2001; El debate Constitucional en la Unión Europea, Revista de Estudios Políticos, nº 113 2001; El Tratado de Niza, Revista Espa- ñola de Derecho Constitucional, nº 59 2001; Sufragio, jueces y de- mocracia en las elecciones norteamericanas de 2000, Jueces para la democracia, n° 40 2001.